Abstract

Purpose

This study reviews paediatric patients with raised intracranial pressure as a result of venous sinus thrombosis secondary to otogenic mastoiditis, requiring admission to the paediatric neuroscience centre at the University Hospital Wales, Cardiff. The consensus regarding the management of otogenic hydrocephalus in the published literature is inconsistent, with a trend towards conservative over surgical management. We reviewed our management of this condition over a 9-year period especially with regard to ventriculo-peritoneal (VP) shunting.

Methods

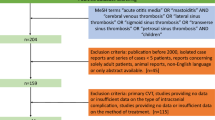

Analysis of a prospectively collected database of paediatric surgical patients was analysed and patients diagnosed with otogenic hydrocephalus from November 2010 to August 2018 were identified. Our data was compared with the published literature on this condition.

Results

Eleven children, 7 males and 4 females, were diagnosed with otogenic hydrocephalus over the 9-year period. Five (45.5%) required VP shunt insertion to manage their intracranial pressure and protect their vision. The remaining six patients (54.5%) were managed medically.

Conclusions

When children with mastoiditis and venous sinus thrombosis progress to having symptoms or signs of raised intracranial pressure, they should ideally be managed within a neuroscience centre. Of those children, almost half will need permanent cerebrospinal fluid diversion to protect their sight.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Otogenic venous sinus thrombosis is a rare intracranial complication of mastoiditis and acute otitis media [1]. Its incidence has reduced significantly since the widespread use of contemporary antimicrobials [2]. However, it remains a serious complication of mastoiditis that needs prompt recognition and treatment to prevent further intracranial sequalae such as raised intracranial pressure (ICP). Patients who develop raised intracranial pressure (otogenic hydrocephalus) require specialist management to manage symptoms and prevent permanent loss of vision [3].

However, the consensus regarding the treatment of otogenic hydrocephalus in the published literature is inconsistent, with a trend towards conservative over surgical management [4]. The indications for conservative over surgical management of raised ICP also remain unclear from the published literature.

In this study, we review our case series of paediatric patients with otogenic hydrocephalus treated within a tertiary referral neuroscience centre. We compared our cohort to the published literature with regard to the need for cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) division.

Methods

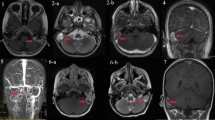

Data on all patients with otogenic hydrocephalus treated at the University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, UK, between November 2010 and August 2018 was collected. Data collected included patient demographics, clinical presentation, radiological findings, medical therapy and neurosurgical management. All patients were admitted jointly under paediatric neurology and paediatric neurosurgery.

Results

Eleven patients with otogenic hydrocephalus secondary to mastoiditis and venous sinus thrombosis were identified between November 2010 and August 2018 (Table 1). Of the 11 patients, 7 (64%) were male and 4 (36%) female with a mean age of 5.7 years at diagnosis. All 11 patients had symptoms of raised intracranial pressure. Eight out of 11 (73%) patients had papilledema, 4/11 (36%) had abducens nerve palsy, 4/11 (36%) strabismus, (36%) 4/11 visual field defects and 1/11 (9%) seizures.

Seven (64%) patients underwent lumbar puncture (LP) for diagnostic and symptomatic relief. Two out of 6 patients without a ventricular peritoneal (VP) shunt had a LP with a mean opening pressure of 45 cm H20. Five out of five children who had a VP shunt had LP with a mean opening pressure of 58.2 cm H20. Four patients (36%) had intracranial pressure monitoring as part of their work up for otitic hydrocephalus. All four went on to have a VP shunts.

Overall a VP shunt was required in 5 patients (45.5%) and the remaining six patients (54.5%) had their raised ICP treated medically.

Discussion

Otitic hydrocephalus develops secondary to venous sinus thrombosis as a result of an inflammatory response to mastoiditis [5]. Following an otogenic infection, secondary inflammation may cause thrombophlebitis of the cerebral veins leading to venous sinus thrombosis. Due to its close anatomical location, the sigmoid sinus is the most commonly affected but local spread to adjacent dural sinuses may also occur [1]. The thrombosis disrupts both venous and CSF drainage in the brain resulting in raised ICP.

The vast majority of patients with mastoiditis remain in their local centres for treatment; however, in South Wales, patients with signs and symptoms of raised ICP are transferred to the paediatric neuroscience centre. Therefore, patients seen at our centre are those with suspected raised ICP secondary to otitic infection. These patients are jointly managed by paediatric neurosurgery and paediatric neurology.

The current published literature is sparse regarding the management of a raised ICP from otitic hydrocephalus. A literature review of 105 cases of otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis advocated conservative over neurosurgical management of raised ICP [4]. Ninety-four percent of these patients were treated medically; however, less than half of the patients (46/105) were reported to have signs of raised ICP. Only 4/46 (8.7%) of the patients with raised ICP went on to have a VP shunt. A smaller case series of otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis reported 4 out of 9 patients with otitic hydrocephalus [6]. Out of these 4 patients, 2 (50%) required a VP shunt for management of a raised ICP. This is more in keeping with our experience.

There are a number a case report of children needing shunts for otitic hydrocephalus [7,8,9,10,11]. However, they do not reach any conclusions regarding the management of raised ICP or elucidate on the decision-making when to insert a VP shunt.

Our decision to insert a VP shunt is based solely on deteriorating vision in patients not responding to serial lumbar punctures (LPs). Serial lumbar punctures and ICP monitoring are useful adjuncts to the management and investigation of these patients, but neither are used in isolation to decide which patients undergo CSF diversion. The patients who underwent intracranial ICP monitoring all subsequently went on to have VP shunts in our series.

Conclusions

Ventriculo-peritoneal shunts are an effective treatment for patients with otitic hydrocephalus primarily to protect vision. From our experience and a review of the limited literature, up to 50% of these patients with signs and/or symptoms of raised ICP will require a VP shunt. Lumbar puncture and/or ICP monitoring in these children seem to be predictive with regard to needing a shunt. We feel that all patients with mastoiditis and venous sinus thrombosis who have signs or symptoms of raised intracranial pressure should be treated within a paediatric neurosciences centre.

References

Go C, Bernstein JM, de Jong AL, Sulek M, Friedman EM (2000) Intracranial complications of acute mastoiditis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 52(2):143–148

Thompson PL, Gilbert RE, Long PF, Saxena S, Sharland M, Wong IC (2009) Effect of antibiotics for otitis media on mastoiditis in children: a retrospective cohort study using the United Kingdom general practice research database. Pediatrics 123(2):424–430

Manolidis S, Kutz JW (2005) Diagnosis and management of lateral sinus thrombosis. Otol Neurotol 26:1045–1051

Scherer A, Jea A (2017) Pediatric otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis: case report and literature reappraisal. Glob Pediatr Health 4:1–8

Smith JA, Danner CJ (2006) Complications of chronic otitis media and cholesteatoma. Otolaryngol Clin N Am 39(6):1237–1255

Bradley DT, Hashisaki GT, Mason JC (2002) Otogenic sigmoid sinus thrombosis: what is the role of anticoagulation. Laryngoscope 112(10):1726–17-29

Viswanatha B (2010) Otitic hydrocephalus: a report of 2 cases. Ear Nose Throat J 89(7):E34–E37. https://doi.org/10.1177/014556131008900708

Velasco-Puyó P, Boronat-Guerrero S, del Toro-Riera M, Vázquez-Méndez E, Roig-Quilis M (2009) Intracranial hypertension associated with cerebral venous sinus thrombosis and mastoiditis. Two paediatic case reports. Rev Neurol 49(10):529–532

Kuczkowsi J, Dubaniewicz-Wybieralska M, Przewoźny T, Narożny MB (2006) Otitic hydrocephalus associated with lateral sinus thrombosis and acute mastoiditis in children. Am J Otolaryngol 70(10):1817–1823

Brito AR, Vasconcelos MM, Domingues RC, Esteves L, Olivaes MC, Cruz LC, Herdy GV (2005) Pseudotumour cerebri secondary to dural sinus thrombosis: pediatric case report. Arg Neuropsiquiatr 63:697–700. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-282X2005000400029

Bari L, Choksi E, Roach EC (2005) Otitic hydrocephalus revisited. Arch Neurol 62:824–825

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bevan, R., Patel, C., Bhatti, I. et al. Surgical management of raised intracranial pressure secondary to otogenic infection and venous sinus thrombosis. Childs Nerv Syst 36, 349–351 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04353-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00381-019-04353-3