Abstract

Each symbiotic Chlorella variabilis associated with the ciliate Paramecium bursaria is enclosed in a symbiosome called the perialgal vacuole. Various potential symbionts, such as bacteria, yeasts, other algae, and free-living Chlorella spp., can infect P. bursaria. However, the detailed infection process of each of them in algae-free P. bursaria is unknown. Here, we aimed to elucidate the difference of the infection process between the free-living C. sorokiniana strain NIES-2169 and native symbiotic C. variabilis strain 1N. We investigated the fate of ingested algae using algae-free P. bursaria exposed separately to three types of algal inocula: NIES-2169 only, 1N only, or a mixture of NIES-2169 and 1N. We found that (1) only one algal species, preferably the native one, was retained in host cells, indicating a type of host compatibility and (2) the algal localization style beneath the host cell cortex varied between different Chlorella spp. showing various levels of host compatibilities, which was prospectively attributable to the difference in the formation of the perialgal vacuole membrane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Upon reasonable request, the datasets used in the current study are available from the corresponding author.

References

Leung TLF, Poulin R (2008) Parasitism, commensalism, and mutualism: exploring the many shades of symbioses. Vie et Milieu. pp 107–115. https://hal.sorbonne-universite.fr/hal-03246057

Davy SK, Allemand D, Weis VM (2012) Cell biology of cnidarian-dinoflagellate symbiosis. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 76:229–261. https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.05014-11

Goetsch W (1924) Die Symbiose der Süsswasser-Hydroiden und ihre künstliche Beeinflussung. Z Morphol Ökol Tiere 1:660

Lee JJ, Soldo AT, Reisser W, Lee M, Jeon KW, Görtz H-D (1985) The extent of algal and bacterial endosymbioses in protozoa. J Protozool 32:391–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb04034.x

Pröschold T, Darienko T, Silva PC, Reisser W, Krienitz L (2011) The systematics of “Zoochlorella” revisited employing an integrative approach. Environ Microbiol 13:350–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02333.x

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2009) Localization of perialgal vacuoles beneath the host cell surface is not a prerequisite phenomenon for protection from the host’s lysosomal fusion in the ciliate Parameium bursaria. Protist 160:319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protis.2008.06.001

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2005) Symbiotic Chlorella sp. of the ciliate Paramecium bursaria do not prevent acidification and lysosomal fusion of host digestive vacuole during infection. Protoplasma 225:191–203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-005-0087-5

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2010) Secondary symbiosis between Paramecium and Chlorella cells. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol 279:33–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1937-6448(10)79002-X

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2009) Timing of perialgal vacuole membrane differentiation from digestive vacuole membrane in infection of symbiotic algae Chlorella vulgaris of the ciliate Paramecium bursaria. Protist 160:65–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protis.2008.06.001

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2011) Four important cytological events needed to establish endosymbiosis of symbiotic Chlorella sp. to the algae-free Paramecium bursaria. Jpn J Protozool 44:1–20

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2012) Characteristics of the digestive vacuole membrane of the alga-bearing ciliate Paramecium bursaria. Protist 163:658–670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protis.2011.10.004

Fujishima M, Kodama Y (2022) Mechanisms for establishing primary and secondary endosymbiosis in Paramecium. J Euk Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeu.12901

Blanc G, Duncan G, Agarkova I, Borodovsky M, Gurnon G, Kuo A, Lindquist E, Lucas S, Pangilinan J, Polle J, Salamov A, Terry A, Yamada T, Dunigan DD, Grigoriev IV, Claverie JM, Van Etten JL (2010) The Chlorella variabilis NC64A genome reveals adaptation to photosynthesis, coevolution with viruses, and cryptic sex. Plant Cell 22:2943–2955. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.110.076406

Cheng YH, Liu CFJ, Yu YH, Jhou YT, Fujishima M, Tsai I, Leu JY (2020) Genome plasticity in Paramecium bursaria revealed by population genomics. BMC Biol 18:180. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-020-00912-2

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2007) Infectivity of Chlorella species for the ciliate Paramecium bursaria is not based on sugar residues of their cell wall components, but based on their ability to localize beneath the host cell membrane after escaping from the host digestive vacuole in the early infection process. Protoplasma 231:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-006-0241-8

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2016) Differences in infectivity between endosymbiotic Chlorella variabilis cultivated outside host Paramecium bursaria for 50 years and those immediately isolated from host cells after one year of reendosymbiosis. Biol Open 5(1):55–61. https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.013946

Bomford R (1965) Infection of algae-free Paramecium bursaria with strains of Chlorella, Scenedesmus, and a yeast. J Protozool 12:221–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1965.tb01840.x

Görtz H-D (1982) Infection of Paramecium bursaria with bacteria and yeasts. J Cell Sci 58:445–453. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.58.1.445

Suzaki T, Omura G, Görtz H-D (2003) Infection of symbiont-free Paramecium bursaria with yeasts. Jpn J Protozool 36:17–18 (in Japanese)

Tsukii Y, Harumoto T, Yazaki K (1995) Evidence for viral macronuclear endosymbiont in Paramecium caudatum. J Euk Microbiol 42:109–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01550.x

Dryl S (1959) Antigensic transformation in Paramecium aurelia after homologous antiserum treatment during autogamy and conjugation. J Protozool 6:25

Fujishima M, Nagahara K, Kojima Y (1990) Changes in morphology, buoyant density and protein composition in differentiation from the reproductive short form to the infectious long form of Holospora obtusa, a macronucleus-specific symbiont of the ciliate Paramecium caudatum. Zool Sci 7(5):849–860. https://doi.org/10.34425/zs000785

Agarkova I, Dunigan D, Gurnon J, Greiner T, Barres J, Thiel G, Van Etten JL (2008) Chlorovirus-mediated membrane depolarization of Chlorella alters secondary active transport of solutes. J Virol 82:12181–12190. https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01687-08

Iwai S, Fujita K, Takanishi Y, Fukushi K (2019) Photosynthetic endosymbionts benefit from host’s phagotrophy, including predation on potential competitors. Curr Biol 29:3114.e3–3119.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2019.07.074

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2011) Endosymbiosis of Chlorella species to the ciliate Paramecium bursaria alters the distribution of the host’s trichocysts beneath the host cell cortex. Protoplasma 248:325–337. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-010-0175-z

Kodama Y, Fujishima M (2022) Endosymbiotic Chlorella variabilis reduces mitochondrial number in the ciliate Paramecium bursaria. Sci Rep 12:8216. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12496-8

Ihaka R, Gentleman R (1996) R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J Comp Graph Stat 5:299–314

Summerer M, Sonntag B, Sommaruga R (2007) An experimental test of the symbiosis specificity between the ciliate Paramecium bursaria and strains of the unicellular green alga Chlorella. Environ Microbiol 9(8):2117–2122. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01322.x

Nishijima A, Fujishima M (2007) Chlorella vulgaris and C. sorokiniana cannot be maintained in Paramecium bursaria cell. Jpn J Protozool 40(1):28–29 (in Japanese)

Weis DS, Ayala A (1979) Effect of exposure period and algal concentrations on the frequency of infection of aposymbiotic ciliates by symbiotic algae from Paramecium bursaria. J Protozool 26:245–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1979.tb02772.x

Weis DS (1980) Hypothesis: free maltose and algal cell surface sugars are signals in the infection of Paramecium bursaria by algae. In: Schwemmler W, Schenk HEA (eds) Endocytobiology, vol 1. Walter de Gruyter & Co, Berlin/New York, pp 105–112

Muscatine L, Karakashian SJ, Karakashian MW (1967) Soluble extracellular products of algae symbiotic with a ciliate, a sponge and a mutant hydra. Comp Biochem Physiol 20(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-406X(67)90720-7

Karakashian SJ (1963) Growth of Paramecium bursaria as influenced by the presence of algal symbionts. Physiol Zool 36:52–68

Takeda H, Sekiguchi T, Nunokawa S, Usuki I (1998) Species-specificity of Chlorella for establishment of symbiotic association with Paramecium bursaria. Does infectivity depend upon sugar components of the cell wall? Eur J Protistol 34:133–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0932-4739(98)80023-0

Meints RH, Pardy RL (1980) Quantitative demonstration of cell surface involvement in a plant-animal symbiosis: lectin inhibition of reassociation. J Cell Sci 43:239–251. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.43.1.239

Lin KL, Wang JT, Fang LS (2000) Participation of glycoproteins on zooxanthellal cell walls in the establishment of a symbiotic relationship with the sea anemone, Aiptasia pulchella. Zool Stud 39:172–178

Wood-Charlson EM, Hollingsworth LL, Krupp DA, Weis VM (2006) Lectin/glycan interactions play a role in recognition in a coral/dinoflagellate symbiosis. Cell Microbiol 8:1985–1993. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00765.x

Logan DDK, LaFlamme AC, Weis VM, Davy SK (2010) Flow-cytometric characterisation of the cell-surface glycans of symbiotic dinoflagellates (Symbiodinium spp.). J Phycol 46:525–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-8817.2010.00819.x

Biquand E, Okubo N, Aihara Y, Rolland V, Hayward DC, Hatta M, Minagawa J, Maruyama T, Takahashi S (2017) Acceptable symbiont cell size differs among cnidarian species and may limit symbiont diversity. ISME J 11:1702–1712. https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2017.17

Kodama Y, Sumita H (2022) The ciliate Paramecium bursaria allows budding of symbiotic Chlorella variabilis cells singly from digestive vacuole membrane into the cytoplasm during algal reinfection. Protoplasma 259:117–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-021-01645-x

Karakashian MW, Karakashian SJ (1973) Intracellular digestion and symbiosis in Paramecium bursaria. Exp Cell Res 81:111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4827(73)90117-1

Kodama Y, Nagase M, Takahama A (2017) Symbiotic Chlorella variabilis strain, 1N, can influence the digestive process in the host Paramecium bursaria during early infection. Symbiosis 71:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13199-016-0411-1

Fok AK, Lee Y, Allen RD (1982) The correlation of DV pH and size with the digestive cycle in Paramecium caudatum. J Euk Microbiol 29:409–414. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1550-7408.1982.tb05423.x

Gu FK, Chen L, Ni B, Zhang X (2002) A comparative study on the electron microscopic enzymo-cytochemistry of Paramecium bursaria from light and dark cultures. Eur J Protistol 38:267–278. https://doi.org/10.1078/0932-4739-00875

Karakashian SJ, Rudzinska MA (1981) Inhibition of lysosomal fusion with symbiont containing vacuoles in Paramecium bursaria. Exp Cell Res 131:387–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4827(81)90242-1

Song C, Murata K, Suzaki T (2017) Intracellular symbiosis of algae with possible involvement of mitochondrial dynamics. Sci Rep 7:1221. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-01331-0

Reisser W (1992) Endosymbiotic associations of algae with freshwater protozoa and invertebrates. In: Reisser W (ed) Algae and symbioses: plants, animals, fungi, viruses, interactions explored, vol 1.1. Biopress, Bristol, pp 1–19

Meier R, Lefort-Tran M, Pouphile M, Reisser W, Wiessner W (1984) Comparative freeze-fracture study of perialgal and digestive vacuoles in Paramecium bursaria. J Cell Sci 71:121–140. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.71.1.121

Schüßler A, Schnepf E (1992) Photosynthesis dependent acidification of perialgal vacuoles in the Paramecium bursaria/Chlorella symbiosis: visualization by monensin. Protoplasma 166:218–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01322784

Watanabe K, Motonaga A, Tachibana M, Shimizu T, Watarai M (2022) Francisella novicida can utilize Paramecium bursaria as its potential host. Environ Microbiol Rep 14(1):50–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-2229.13029

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Professor Emeritus Masahiro Fujishima (Yamaguchi University, Japan) for giving us the valuable monoclonal antibody against mitochondria. The authors would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for the English-language editing of the manuscript. The authors thank the faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences in Shimane University for financial supports in publishing this report.

Funding

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (Grant Number 20K06768) and (B) (Grant Number 23H02529) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the Oshimo Foundation (Hiroshima, Japan) to YK.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YK conceived and designed the experiments. YK and YE performed the experiments. YK wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

284_2023_3590_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Supplementary file1 (TIF 4874 KB)

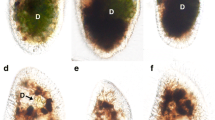

Figure S1. Cytoplasmic streaming in P. bursaria after mixing with NIES-2169 1 h (upper) and 48 h (lower). Micrographs were taken at 10-s intervals at each time point. One hour after mixing with NIES-2169, numerous DV membranes containing NIES-2169 had formed. These DV membranes were rapidly flowing in the cytoplasm due to host cytoplasmic streaming. The black arrow indicates a representative DV. Forty-eight hours after mixing, the vacuoles enclosing multiple NIES-2169 were not flowing by the cytoplasmic streaming, because the vacuole was localized beneath the host cell cortex. Black arrowhead and double black arrowhead show representative vacuoles. This attachment of the vacuole beneath the host cell cortex is a typical feature of PV membrane. Because the host cytoplasmic streaming was suppressed compared to 1 h after the algal mixing, not only the vacuoles enclosing NIES-2169, but also other vacuoles or crystals were barely moving (Data not shown). On the other hand, when 1N cells were ingested, the initial DV membrane flowed by the host cytoplasmic streaming, and the membrane that later encloses a single 1N cell localized beneath the host cell cortex and did not flow as shown in [7]. Ma macronucleus.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kodama, Y., Endoh, Y. Comparative Analyses of the Symbiotic Associations of the Host Paramecium bursaria with Free-Living and Native Symbiotic Species of Chlorella. Curr Microbiol 81, 66 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-023-03590-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-023-03590-9