Abstract

The immunomodulatory fusion protein abatacept has recently been investigated for the treatment of steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGvHD) in a phase 1 clinical trial. We analyzed the safety and efficacy of abatacept for cGvHD therapy in a retrospective study with 15 patients who underwent allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) and received abatacept for cGvHD with a median age of 49 years. Grading was performed as part of the clinical routine according to the National Institute of Health’s (NIH) consensus criteria at initiation of abatacept and 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months thereafter. The median time of follow-up was 191 days (range 55–393 days). Best overall response rate (ORR) was 40%. In particular, patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome showed significant clinical improvement and durable responses following abatacept treatment with a response rate of 89% based on improvement in lung severity score (n = 6) or stabilized lung function (n = 4) or both (n = 3). Infectious complications CTCAE °III or higher were observed in 3/15 patients. None of the patients relapsed from the underlying malignancy. Thus, abatacept appears to be a promising treatment option for cGvHD, in particular for patients with lung involvement. However, further evaluation within a phase 2 clinical trial is required.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

While allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) is a well-established, potentially curative therapy for several malignant and benign hematologic diseases, chronic graft-versus-host disease (cGvHD) remains a major complication after allo-HSCT. cGvHD occurs in up to 70% of patients after allo-HSCT and significantly contributes to impaired quality of life and non-relapse mortality (NRM)/transplant-related mortality (TRM) [1,2,3,4,5].

Corticosteroids represent the backbone of cGVHD treatment, but contribute to an already high morbidity and mortality by causing complications such as osteoporosis, myopathy, avascular necrosis, and glaucoma [3, 6]. A substantial number of patients does not respond to corticosteroids alone and require second-line therapy with the recently FDA-approved Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor ibrutinib or extracorporeal photopheresis [5, 7,8,9]. Further treatment options are usually based on retrospective or phase 1/2 clinical studies and show limited efficacy in a significant proportion of patients despite harboring the risk of toxicity including infectious complications [10,11,12,13,14].

Abatacept is a novel, first in class immunomodulatory drug exerting its effect by costimulatory blockade and is applied for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and other rheumatological diseases [15,16,17]. It is a recombinant fusion protein comprised of the extracellular domain of the immune checkpoint protein cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) fused to the Fc fragment of IgG1 [18]. By binding with high affinity to the costimulatory receptors CD80 and CD86 on antigen presenting cells (APCs), it counteracts the costimulatory signal mediated by the ligand CD28, which is required for full T cell activation [19].

The highly complex pathophysiology of cGvHD is still poorly understood. Apart from alloreactive donor T cell responses, it involves aberrant innate immune signaling, endothelial cell injury, dysfunctional central tolerance induction (due to thymic damage as a result of the conditioning regimen or alloreactive T cells), insufficient de novo development of regulatory T cells (Treg), dysregulation of B cells, and cytokine signaling eventually resulting in chronic inflammation and fibrotic remodeling [20,21,22].

Since cGvHD is at least in part mediated by host reactive T cells stimulated by allogeneic antigens [23], there is high rationale for abatacept as a treatment option in cGvHD, and it has been reported that CTLA-4 blockade can prevent aGvHD and cGvHD and even reverse cGvHD in murine models [24]. Recently, abatacept has received breakthrough approval by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the prevention of acute GvHD and has shown efficacy in a phase 1 clinical trial for patients with steroid-refractory cGvHD, albeit with relatively low patient numbers [25].

Therefore, we analyzed the efficacy and safety of abatacept for the treatment of advanced cGvHD in a multicentric retrospective study.

Patients and methods

Patients

In this retrospective analysis, patients treated with abatacept for cGvHD between 2018 and 2020 at the University Hospital Regensburg (Germany), University Hospital Giessen and Marburg (Germany), University Hospital and Karolinska Institutet (Stockholm, Sweden) and University Hospital La Paz (Madrid, Spain) were included into the analysis approved by the institutional ethics review board (no.19-1586-104). Documentation of cGvHD was performed as part of clinical routine using the diagnosis and response criteria according to the National Institute of Health (NIH) consensus guidelines [26]. No new immunosuppressive agent was applied within at least 4 weeks before abatacept therapy, and response assessment was discontinued upon requirement of any additional immunosuppressive treatment post abatacept therapy. Patients received abatacept intravenously at a dose of 10 mg/kg body weight (maximum 800 mg) every 2 weeks for the first three doses and then every 4 weeks.

Definition of abatacept response and adverse events

Response to abatacept was assessed at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after start of therapy. In case of treatment with an additional immunosuppressive agent, the last response assessment for abatacept was performed at onset of new therapy. Last follow-up of the present analysis was January 2020. Complete remission (CR) was defined as resolution of all organ manifestations of cGvHD. Improvement of at least one organ grade without progression of cGvHD at other organs was classified as partial response (PR); mixed response was defined as simultaneous improvement in one organ and progression in another organ. Patients who showed no change in organ grading were classified as stable disease (SD). Failure-free survival (FFS) was defined as absence of relapse or non-relapse mortality or addition of further systemic therapy. Overall response rates (ORR) were calculated based on intention to treat analysis. Infectious complications were assessed and classified according to the common terminology criteria for adverse events version 5.0 (CTCAE 5.0) with toxicities captured in the analysis starting from grade III.

Results

Patient characteristics

We treated 15 patients with abatacept for cGvHD at our centers between 2018 and 2020. Among those patients, the diagnoses leading to allo-HSCT were myeloid disorders (acute myeloid leukemia (AML), myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), myeloproliferative neoplasia (MPN)) in 10 patients, lymphatic malignancies (acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), and Hodgkin lymphoma (HL)) in four patients and one patient suffering from CTLA-4 haploinsufficiency.

All patients had received peripheral blood stem cells (PBSC) as graft source with 11 patients grafted from an HLA-matched sibling (5 patients) or an unrelated donor (8 patients). HLA-matched donors were defined as 10/10 match. One patient had received an HLA-C mismatched graft from an unrelated donor, and one patient received a haploidentical graft from a related donor. Acute GvHD grade II or higher according to Glucksberg criteria occurred in 11 patients (85%). cGvHD onset was quiescent in 8 patients, de novo in three patients and progressive in four patients. Most of the patients (n = 12; 80%), who received abatacept, had severe cGvHD. One patient included in the analysis had mild cGvHD (prior history of moderate cGvHD) and received abatacept due to intolerance to other immunosuppressive agents. One patient was treated for autoimmune-hemolytic anemia (AIHA) refractory to corticosteroids and rituximab not fulfilling the NIH criteria for cGvHD falling in the category “undefined other cGvHD” [26, 27]. The majority of the patients had steroid dependent cGvHD (n = 10, 67%, all others steroid-refractory cGvHD (n = 5; 33%)). A platelet count < 100/nl was observed in 4 patients (27%) at the time of abatacept initiation.

The most common organ manifestations of cGvHD were skin (n = 11; 73%), lung (n = 11; 73%), eyes (n = 10; 67%), and oral cavity (n = 10; 67%). Abatacept was initiated on median day 1848 (range 432–7953) after allo-HSCT and on day 1592 (range 28–7864) after cGvHD onset, respectively. The corticosteroid dose at abatacept initiation was 0.34 mg/kg in median (range 0,12–2 mg/kg). The patients included in the analysis had received a median of 4.6 prior treatment lines (range 2–5) for cGvHD. Within 3 months before abatacept treatment was started, most patients did not undergo new immunosuppressive treatments (80%). The remaining patients (20%), who underwent new immunosuppressive treatments within 3 months, were progressive or refractory to the initiated treatment.

Median follow-up after treatment was 179 days (range 55–393). Patient characteristics including age, gender, diagnosis, donor type, stem cell source, conditioning regimen, GvHD prophylaxis, history of acute GvHD, and chronic GvHD are shown in Table 1.

Response to abatacept

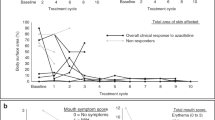

Response to abatacept treatment is illustrated in Fig. 1 and Table 2 at the different time points of this analysis.

Response to abatacept at 1 month

One month after first administration of abatacept, the patient (7%) with AIHA showed CR, 5 (33%) patients had PR, one patient (7%) showed MR with improved lung function but progressive oral affection, and 8 patients (53%) presented with SD. None of the patients required start of an additional immunosuppressive therapy. The overall response rate (ORR) at 1 month was 40%, and failure-free survival (FFS) was 100%.

Response to abatacept at 3 months

At 3 months after start of abatacept therapy, one patient showed CR (7%), 5 (33%) patients had PR, one patient showed MR (7%), and 6 patients (40%) had SD. One patient who had SD started a new immunosuppression and another patient with a PR succumbed to infectious complications of severe peripheral artery disease unrelated to abatacept. ORR at 3 months was therefore 40% with an FFS of 87%.

Response to abatacept at 6 and 9 months

The 6 months follow-up was reached by nine patients with one patient remaining in CR (7%), four patients achieving PR (27%), one MR (7%) with sustained stabilized lung function but impaired oral affection, and two patients with SD (13%). At termination of our analysis, one patient was still treated with abatacept but has not reached the 6 months follow-up yet. One patient with PR started a new IS with ibrutinib and tocilizumab, and another patient who was in SD discontinued abatacept and was switched to tofacitinib due to persisting arthralgia. One highly comorbid patient with preexisting aortic valve insufficiency died due to aortic valve rupture. Thus, the ORR at 6 months was 33% with an FFS of 64%.

Nine months after initiation of abatacept treatment, four patients still received therapy and two patients currently still receiving abatacept have not reached the time point yet. Of the remaining patients, three showed a PR (20%), one patient discontinued abatacept due to sustained and not improved oral ulcers, and another patient died due to urosepsis, displaying an ORR of 23% with an FFS of 31%.

Response to abatacept at 12 months

At 12 months, three patients were still treated with abatacept, and three who currently receive abatacept therapy have not reached the time point yet. Three patients still had PR (25%) resulting in an ORR of 25% with FFS of 25%.

Response in patients with lung involvement of cGvHD

Interestingly, we observed that patients with lung involvement (n = 9) particularly benefitted from therapy with abatacept with an overall response rate of 89% based on improvement in lung severity score (n = 6), lung function as measured by FEV1 in Fig. 1 (n = 4) or both (n = 3). Of note, although only a stabilization on abatacept was achieved, they experienced prior constant loss of FEV1 as shown in Fig. 1. Of note, all patients received in parallel therapy with FAM (fluticasone, azithromycine, montelukast) partly in combination with beta-agonists which had already been applied > 1 month before abatacept initiation without response (Fig. 2).

Infectious and other complications during abatacept

Adverse events (AE) and serious adverse events (SAE) during abatacept treatment are illustrated in Table 3. In general, abatacept administration was well tolerated; however, one patient repeatedly showed nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, fever, and fatigue for several days repeatedly upon infusion leading to termination of treatment after 7 applications. Another patient showed alopecia during treatment. Three of the patients included in the analysis developed significant infectious complications requiring hospital admission with one highly comorbid patient succumbing to urosepsis, and another patient already mentioned died due to infectious complications associated with severe peripheral artery disease unrelated to cGvHD.

Discussion

cGvHD occurs with an incidence of 30–70% in patients undergoing allo-HSCT [21], and as it reduces quality of life and significantly contributes to NRM/TRM, there is still a high clinical need for effective second-line treatments [28, 29]. The underlying complex pathophysiology of cGvHD involves both B and T cell immunity and results in pleiotropic clinical manifestations resembling various autoimmune diseases [21]. Due to the involvement of auto- und alloreactive T cells in the development and course of cGvHD, there is high rationale for the use of costimulation blockade via the CTLA-4 pathway [20]. The introduction of the immunomodulatory drug abatacept has significantly improved the therapy for rheumatoid arthritis patients not responding sufficiently to conventional disease modifying antirheumatic drugs and has in this context shown efficacy and improvement of quality of life [19, 30, 31]. Based on observations in preclinical models, abatacept has been tested in combination with a CD25 monoclonal antibody in pediatric recipients of haploidentical allo-HSCT for the treatment of hyperacute GvHD, where it has shown efficacy [32]. Moreover, the safety and efficacy of abatacept for the prevention of aGvHD and treatment of SR-cGvHD were recently evaluated with promising results in phase 1 clinical trials [25, 33], and subsequent randomized phase 2 trials have been initiated (NCT0174313; NCT01954979).

In this retrospective analysis of cGvHD patients treated with abatacept at four centers, we observed a best overall response rate of 40%, which is comparable to the clinical response rate of 44% recently reported by Nahas et al. [25]. Despite the low number of patients and the retrospective character of the analysis, we observed that in particular patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) showed substantial clinical improvement after abatacept application with durable responses, stabilized lung function (Fig. 1), albeit this was not reflected by an improvement in lung grading in all patients. Given the frequently irreversible character of lung involvement due to fibrotic remodeling, we consider clinical improvement, lowering of oxygen demand, and stabilized lung function as relevant response parameters, especially in our patient cohort with mostly severe cGVHD [34]. Interestingly, it has been reported for several autoimmune diseases that costimulation blockade of the CTLA-4 axis selectively decreases the proportion of T follicular helper cells, thereby reducing T cell help for germinal center B cells [35,36,37]. Given that BOS is explicitly characterized by disturbance of B cell homeostasis with increased CD19+CD21- B cells and excess of B cell activation factor (BAFF) [38], abatacept might target Tfh cells in this context, which would at least partially explain the particular improvement of patients with BOS in our study. In addition, we observed a complete response in a steroid and rituximab refractory AIHA patient as previously described [39]. Despite not meeting NIH diagnostic criteria for cGvHD, we included this patient in our analysis since it has recently been reported that based on biomarker profiles, patients with signs of immune mediated damage not diagnostic for cGvHD do not significantly differ from those showing diagnostic signs of cGvHD suggesting that the current NIH diagnostic criteria may not involve all targets of cGvHD [40, 41]. Noteworthy, in the phase 1 clinical trial reported by Nahas et al., a reduction of corticosteroid usage of 51.3% was reported, while the authors state that this effect might have been overestimated due to the not blinded or randomized design of the study. In this regard, we did not observe consistent steroid reduction in patients responding to abatacept, yet most of our patients received a relatively low corticosteroid dose at start of abatacept. Interestingly, it has been reported in a preclinical model of chronic lung allograft dysfunction that bronchiolitis obliterans can be attenuated by CTLA-4-Ig administration presumably by promoting LAG3+Treg mediated anti-inflammatory effects providing a potential mechanistic explanation for the observed clinical response [42]. Of note, progression of cGvHD within three months was indicative for treatment failure, and all patients, who achieved at least a PR, were responding in the first three months. Thus, based on our experience, we would suggest discontinuing abatacept treatment, if patients do not show a response within this period. Overall, abatacept seems to be a relevant treatment option for patients with cGvHD, particularly for patients with BOS, but this has to be further investigated in future clinical trials.

References

Socié G, Ritz J (2014 Jul 17) Current issues in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 124(3):374–384

Fraser CJ, Bhatia S, Ness K, Carter A, Francisco L, Arora M, Parker P, Forman S, Weisdorf D, Gurney JG, Baker KS (2006 Oct 15) Impact of chronic graft-versus-host disease on the health status of hematopoietic cell transplantation survivors: a report from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor Study. Blood. 108(8):2867–2873

Pidala J, Kurland B, Chai X, Majhail N, Weisdorf DJ, Pavletic S, Cutler C, Jacobsohn D, Palmer J, Arai S, Jagasia M, Lee SJ (2011 Apr 28) Patient-reported quality of life is associated with severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease as measured by NIH criteria: report on baseline data from the Chronic GVHD Consortium. Blood. 117(17):4651–4657

Arai S, Arora M, Wang T, Spellman SR, He W, Couriel DR, Urbano-Ispizua A, Cutler CS, Bacigalupo AA, Battiwalla M, Flowers ME, Juckett MB, Lee SJ, Loren AW, Klumpp TR, Prockup SE, Ringdén OT, Savani BN, Socié G, Schultz KR, Spitzer T, Teshima T, Bredeson CN, Jacobsohn DA, Hayashi RJ, Drobyski WR, Frangoul HA, Akpek G, Ho VT, Lewis VA, Gale RP, Koreth J, Chao NJ, Aljurf MD, Cooper BW, Laughlin MJ, Hsu JW, Hematti P, Verdonck LF, Solh MM, Norkin M, Reddy V, Martino R, Gadalla S, Goldberg JD, McCarthy P, Pérez-Simón JA, Khera N, Lewis ID, Atsuta Y, Olsson RF, Saber W, Waller EK, Blaise D, Pidala JA, Martin PJ, Satwani P, Bornhäuser M, Inamoto Y, Weisdorf DJ, Horowitz MM, Pavletic SZ, Graft-vs-Host Disease Working Committee of the CIBMTR (2015 Feb 1) Increasing incidence of chronic graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic transplantation: a report from the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21(2):266–274

Wolff D, Gerbitz A, Ayuk F, Kiani A, Hildebrandt GC, Vogelsang GB, Elad S, Lawitschka A, Socie G, Pavletic SZ, Holler E, Greinix H (2010 Dec) Consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD): first-Line and topical treatment of chronic GVHD. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16(12):1611–1628

Stanbury RM, Graham EM (1998 Jun 1) Systemic corticosteroid therapy---side effects and their management. Br J Ophthalmol 82(6):704–708

Wolff D, Schleuning M, von Harsdorf S, Bacher U, Gerbitz A, Stadler M, Ayuk F, Kiani A, Schwerdtfeger R, Vogelsang GB, Kobbe G, Gramatzki M, Lawitschka A, Mohty M, Pavletic SZ, Greinix H, Holler E (2011 Jan) Consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic GVHD: second-line treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17(1):1–17

Miklos D, Cutler CS, Arora M, Waller EK, Jagasia M, Pusic I, Flowers ME, Logan AC, Nakamura R, Blazar BR, Li Y, Chang S, Lal I, Dubovsky J, James DF, Styles L, Jaglowski S (2017 Nov 23) Ibrutinib for chronic graft-versus-host disease after failure of prior therapy. Blood. 130(21):2243–2250

Flowers MED, Apperley JF, van Besien K, Elmaagacli A, Grigg A, Reddy V, Bacigalupo A, Kolb HJ, Bouzas L, Michallet M, Prince HM, Knobler R, Parenti D, Gallo J, Greinix HT (2008 Oct 1) A multicenter prospective phase 2 randomized study of extracorporeal photopheresis for treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 112(7):2667–2674

Zeiser R, Burchert A, Lengerke C, Verbeek M, Maas-Bauer K, Metzelder SK, Spoerl S, Ditschkowski M, Ecsedi M, Sockel K, Ayuk F, Ajib S, de Fontbrune FS, Na IK, Penter L, Holtick U, Wolf D, Schuler E, Meyer E, Apostolova P, Bertz H, Marks R, Lübbert M, Wäsch R, Scheid C, Stölzel F, Ordemann R, Bug G, Kobbe G, Negrin R, Brune M, Spyridonidis A, Schmitt-Gräff A, van der Velden W, Huls G, Mielke S, Grigoleit GU, Kuball J, Flynn R, Ihorst G, du J, Blazar BR, Arnold R, Kröger N, Passweg J, Halter J, Socié G, Beelen D, Peschel C, Neubauer A, Finke J, Duyster J, von Bubnoff N (2015 Oct) Ruxolitinib in corticosteroid-refractory graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic stem cell transplantation: a multicenter survey. Leukemia. 29(10):2062–2068

Cutler C, Miklos D, Kim HT, Treister N, Woo S-B, Bienfang D, Klickstein LB, Levin J, Miller K, Reynolds C, Macdonell R, Pasek M, Lee SJ, Ho V, Soiffer R, Antin JH, Ritz J, Alyea E (2006 Jul 15) Rituximab for steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 108(2):756–762

Klobuch S, Weber D, Holler B, Edinger M, Herr W, Holler E, Wolff D (2019 Oct 1) Long-term follow-up of rituximab in treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease—single center experience. Ann Hematol 98(10):2399–2405

Wolf D, von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Wolf AM, Schleuning M, von Bergwelt-Baildon M, Held SAE, Brossart P (2012 Jan 5) Novel treatment concepts for graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 119(1):16–25

Fante MA, Holler B, Weber D, Angstwurm K, Bergler T, Holler E, Edinger M, Herr W, Wertheimer T, Wolff D (2020 Sep 1) Cyclophosphamide for salvage therapy of chronic graft-versus-host disease: a retrospective analysis. Ann Hematol 99(9):2181–2190

Genovese MC, Becker J-C, Schiff M, Luggen M, Sherrer Y, Kremer J, Birbara C, Box J, Natarajan K, Nuamah I, Li T, Aranda R, Hagerty DT, Dougados M (2005 Sep 15) Abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis refractory to tumor necrosis factor α inhibition. N Engl J Med 353(11):1114–1123

Simon TA, Soule BP, Hochberg M, Fleming D, Torbeyns A, Banerjee S, Boers M (2019) Safety of abatacept versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis: Integrated data analysis of nine clinical trials. ACR Open Rheumatology 1:251–257. https://doi.org/10.1002/acr2.1034

Mease PJ, Gottlieb AB, van der Heijde D, FitzGerald O, Johnsen A, Nys M, Banerjee S, Gladman DD (2017 Sep 1) Efficacy and safety of abatacept, a T cell modulator, in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III study in psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 76(9):1550–1558

Moreland L, Bate G, Kirkpatrick P (2006 Mar) Abatacept. Nat Rev Drug Discov 5(3):185–186

Kremer JM, Westhovens R, Leon M, Di Giorgio E, Alten R, Steinfeld S et al (2003) Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis by selective inhibition of T cell activation with fusion protein CTLA4Ig. N Engl J Med 349(20):1907–1915

Ghimire S, Weber D, Mavin E, Wang XN, Dickinson AM, Holler E (2017) Pathophysiology of GvHD and other HSCT-related major complications. Front Immunol [Internet] 8 [cited 2020 Jan 27] Available from: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00079/full

Zeiser R, Blazar BR (2017 Dec 28) Pathophysiology of chronic graft-versus-host disease and therapeutic targets. Longo DL, editor. N Engl J Med 377(26):2565–2579

Wertheimer T, Velardi E, Tsai J, Cooper K, Xiao S, Kloss CC et al (2018 Jan 12) Production of BMP4 by endothelial cells is crucial for endogenous thymic regeneration. Sci Immunol 3(19):eaal2736

Cooke KR, Luznik L, Sarantopoulos S, Hakim FT, Jagasia M, Fowler DH, van den Brink MRM, Hansen JA, Parkman R, Miklos DB, Martin PJ, Paczesny S, Vogelsang G, Pavletic S, Ritz J, Schultz KR, Blazar BR (2017 Feb) The biology of chronic graft-versus-host disease: a task force report from the National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for clinical trials in chronic graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 23(2):211–234

Via CS, Rus V, Nguyen P, Linsley P, Gause WC (1996 Nov 1) Differential effect of CTLA4Ig on murine graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) development: CTLA4Ig prevents both acute and chronic GVHD development but reverses only chronic GVHD. J Immunol 157(9):4258

Nahas MR, Soiffer RJ, Kim HT, Alyea EP, Arnason J, Joyce R et al (2018 Jun 21) Phase 1 clinical trial evaluating abatacept in patients with steroid-refractory chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 131(25):2836–2845

Jagasia MH, Greinix HT, Arora M, Williams KM, Wolff D, Cowen EW et al (2015 Mar) National Institutes of Health Consensus Development Project on Criteria for Clinical Trials in Chronic Graft-versus-Host Disease: I. The 2014 Diagnosis and Staging Working Group Report. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 21(3):389–401.e1

on behalf of the EBMT (European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation) Transplant Complications Working Party and the “EBMT−NIH (National Institutes of Health) − CIBMTR (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research) GvHD Task Force,”, Schoemans HM, Lee SJ, Ferrara JL, Wolff D, Levine JE et al (2018 Nov) EBMT−NIH − CIBMTR Task Force position statement on standardized terminology & guidance for graft-versus-host disease assessment. Bone Marrow Transplant 53(11):1401–1415

Garnett C, Apperley JF, Pavlů J (2013 Dec) Treatment and management of graft- versus -host disease: improving response and survival. Therapeutic Adv Hematol 4(6):366–378

Flowers MED, Martin PJ (2015 Jan 22) How we treat chronic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 125(4):606–615

Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Mouy R, Paz E, Rubio-Pérez N, Silva CA, Abud-Mendoza C, Burgos-Vargas R, Gerloni V, Melo-Gomes JA, Saad-Magalhaes C, Chavez-Corrales J, Huemer C, Kivitz A, Blanco FJ, Foeldvari I, Hofer M, Huppertz HI, Job Deslandre C, Minden K, Punaro M, Block AJ, Giannini EH, Martini A, for the Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group and the Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation (2015 Oct) Long-term safety, efficacy, and quality of life in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis treated with intravenous abatacept for up to seven years: outcome of long-term abatacept treatment IN JIA. Arthritis Rheum 67(10):2759–2770

Weinblatt ME, Moreland LW, Westhovens R, Cohen RB, Kelly SM, Khan N, Pappu R, Delaet I, Luo A, Gujrathi S, Hochberg MC (2013 Jun) safety of abatacept administered intravenously in treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: integrated analyses of up to 8 years of treatment from the abatacept clinical trial program. J Rheumatol 40(6):787–797

Jaiswal SR, Zaman S, Chakrabarti A, Sehrawat A, Bansal S, Gupta M, Chakrabarti S (2016 Nov 1) T cell costimulation blockade for hyperacute steroid refractory graft versus-host disease in children undergoing haploidentical transplantation. Transpl Immunol 39:46–51

Koura DT, Horan JT, Langston AA, Qayed M, Mehta A, Khoury HJ, Harvey RD, Suessmuth Y, Couture C, Carr J, Grizzle A, Johnson HR, Cheeseman JA, Conger JA, Robertson J, Stempora L, Johnson BE, Garrett A, Kirk AD, Larsen CP, Waller EK, Kean LS (2013 Nov) In vivo T cell costimulation blockade with abatacept for acute graft-versus-host disease prevention: a first-in-disease trial. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 19(11):1638–1649

Hildebrandt GC, Fazekas T, Lawitschka A, Bertz H, Greinix H, Halter J, Pavletic SZ, Holler E, Wolff D (2011 Oct 1) Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary chronic GVHD: report from the consensus conference on clinical practice in chronic GVHD. Bone Marrow Transplant 46(10):1283–1295

Shunsuke F, Nakayamada. Abatacept therapy reduces CD28 + CXCR5+ follicular helper-like T cells in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Glatigny S, Höllbacher B, Motley SJ et al (2019) Abatacept targets T follicular helper and regulatory T cells, disrupting molecular pathways that regulate their proliferation and maintenance. J Immunol (Baltimore, Md.: 1950) 202(5):1373–1382. https://doi.org/10.4049/jimmunol.1801425

Edner NM, Heuts F, Thomas N, Wang CJ, Petersone L, Kenefeck R, Kogimtzis A, Ovcinnikovs V, Ross EM, Ntavli E, Elfaki Y, Eichmann M, Baptista R, Ambery P, Jermutus L, Peakman M, Rosenthal M, Walker LSK (2020 Oct 1) Follicular helper T cell profiles predict response to costimulation blockade in type 1 diabetes. Nat Immunol 21(10):1244–1255

Kuzmina Z, Weigl R, Krenn K, Petkov V, Koermoeczi U, Rottal A, Zielinski C, Greinix HT, Pickl W (2010 Nov 19) Disturbance of B cell homeostasis in chronic graft-versus-host disease of the lung. Blood. 116(21):900–900

Hess J, Su L, Nizzi F, Beebe K, Magee K, Salzberg D, Stahlecker J, Miller HK, Adams RH, Ngwube A (2018 Sep 1) Successful treatment of severe refractory autoimmune hemolytic anemia after hematopoietic stem cell transplant with abatacept. Transfusion. 58(9):2122–2127

Wolff D (2020 Apr 9) A few steps on the long road toward biomarkers in GVHD. Blood. 135(15):1196–1197

Schultz KR, Kariminia A, Ng B, Abdossamadi S, Lauener M, Nemecek ER, Wahlstrom JT, Kitko CL, Lewis VA, Schechter T, Jacobsohn DA, Harris AC, Pulsipher MA, Bittencourt H, Choi SW, Caywood EH, Kasow KA, Bhatia M, Oshrine BR, Flower A, Chaudhury S, Coulter D, Chewning JH, Joyce M, Savasan S, Pawlowska AB, Megason GC, Mitchell D, Cheerva AC, Lawitschka A, Azadpour S, Ostroumov E, Subrt P, Halevy A, Mostafavi S, Cuvelier GDE (2020 Apr 9) Immune profile differences between chronic GVHD and late acute GVHD: results of the ABLE/PBMTC 1202 studies. Blood. 135(15):1287–1298

Suzuki Y, Oishi H, Kanehira M, Matsuda Y, Sado T, Noda M, Funahashi J, Sakurada A, Okada Y (2019 Apr 1) CTLA4-Ig therapy attenuates bronchiolitis obliterans after mouse intrapulmonary trachial transplantation model through possibility of effect of LAG3 + Tregs. J Heart Lung Transplant 38(4):S250

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation) - Projekt-ID 324392634 - TRR221, subproject B10 (D.W.), and by the ReForM program of the University of Regensburg (T.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

D. W. received honoraria from Mallinckrodt, Novartis, Takeda, MACO, and Neovii.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wertheimer, T., Dohse, M., Afram, G. et al. Abatacept as salvage therapy in chronic graft-versus-host disease—a retrospective analysis. Ann Hematol 100, 779–787 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-021-04434-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-021-04434-x