Abstract

Rationale

Acute tryptophan depletion (ATD) decreases levels of central serotonin. ATD thus enables the cognitive effects of serotonin to be studied, with implications for the understanding of psychiatric conditions, including depression.

Objective

To determine the role of serotonin in conscious (explicit) and unconscious/incidental processing of emotional information.

Materials and methods

A randomized, double-blind, cross-over design was used with 15 healthy female participants. Subjective mood was recorded at baseline and after 4 h, when participants performed an explicit emotional face processing task, and a task eliciting unconscious processing of emotionally aversive and neutral images presented subliminally using backward masking.

Results

ATD was associated with a robust reduction in plasma tryptophan at 4 h but had no effect on mood or autonomic physiology. ATD was associated with significantly lower attractiveness ratings for happy faces and attenuation of intensity/arousal ratings of angry faces. ATD also reduced overall reaction times on the unconscious perception task, but there was no interaction with emotional content of masked stimuli. ATD did not affect breakthrough perception (accuracy in identification) of masked images.

Conclusions

ATD attenuates the attractiveness of positive faces and the negative intensity of threatening faces, suggesting that serotonin contributes specifically to the appraisal of the social salience of both positive and negative salient social emotional cues. We found no evidence that serotonin affects unconscious processing of negative emotional stimuli. These novel findings implicate serotonin in conscious aspects of active social and behavioural engagement and extend knowledge regarding the effects of ATD on emotional perception.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) has been implicated in human motivational behaviours and processes, including affect regulation, impulse control, sexuality, appetite and sleep. Serotonin dysfunction is also linked to a number of psychiatric disorders, including depression (Caspi et al. 2003), anxiety (Lesch et al. 1996), and schizophrenia (Juckel et al. 2008). In particular, the ‘serotonin hypothesis of depression’ proposes that a deficit in serotonergic activity either causes or predisposes to major depression (Maes and Meltzer 1995). Consistent with this, the majority of antidepressant drugs enhance serotonergic activity (Blier and Bouchard 1994).

The contributions of serotonin to cognitive and emotional processing can be inferred indirectly from studies of depressed patients. However, acute depression is associated with the confounds of negative biases in information processing, affecting memory and attention (Bradley et al. 1995; MacLeod et al. 1986) and face perception (Surguladze et al. 2004). The effects of serotonin can be studied experimentally, without the confound of low mood, using acute tryptophan depletion (ATD), a well-established method to lower central 5-HT levels (Nishizawa et al. 1997).

Several studies report that ATD in healthy people induces a negative bias in emotional processing across experimental paradigms, similar to that seen in depressed patients. For example, ATD compromises memory for neutral and positive, but not negative, words (Klaassen et al. 2002) and enhances the interference effect of negative, but not positive, words in emotional Stroop tasks (Evers et al. 2006). There is also evidence that ATD selectively alters the processing of emotional facial expressions: ATD is reported to decrease recognition of fearful, but not other, facial expressions, in healthy females (Harmer et al. 2003). Conversely, acute administration of tryptophan may improve recognition of emotional facial expressions (Attenburrow et al. 2003) and administration of a selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) increases the recognition of facial fear cues (Harmer et al. 2002). Face processing is particularly important to human social cognition, as faces convey a rich variety of socially relevant information beyond identity, gender and age, by also signalling emotional state, intentions and sexual fitness. The above considerations suggest that face processing may be one route through which serotonin affects social cognition.

Stimuli processed below the threshold for conscious awareness can significantly influence various aspects of human behaviour (Kouider and Dehaene 2007). One of the most established techniques for suppressing conscious awareness of a stimulus is ‘backward masking’, where a target image is presented very briefly (typically 20–40 ms) and is immediately followed by the presentation of a distracter image which ‘masks’, or blocks, the conscious processing of the initial stimulus. Comparisons between conscious and unconscious aspects of emotional processing provide insight into the levels of processing at which behaviour is influenced. Existing literature indicates that serotonin levels can influence mood and explicit declarative emotion recognition. We explored first, whether ATD was associated with tonic differences in behavioural ratings and reaction time responses, and second if ATD affected the reactivity of different axes of autonomic bodily response to emotional stimuli. While characteristic changes in autonomic tone (parasympathetic withdrawal) and enhanced autonomic reactivity are reported in depression and other psychiatric conditions (Bar et al. 2004; Bar et al. 2008), there is a paucity of studies examining the effects of ATD on visceral bodily responses.

To characterize further the role of serotonin in emotional processing, to explore the levels of attention at which this occurs and to investigate the physiological mechanisms which might mediate these effects, we used double-blind, cross-over ATD to temporarily reduce serotonin levels in 15 healthy female volunteers. We examined performance during explicit processing of emotional facial expressions and on a task involving unconscious processing of aversive and neutral stimuli, presented using backward masking. We recorded evoked physiological changes in heart rate (inter-beat interval), beat-to-beat blood pressure and electrodermal activity (skin conductance response; SCR).

Our general prediction was that ATD would enhance processing of negative stimuli. Specifically, we hypothesized that ATD would enhance the intensity of angry faces, based on a prior study (Harmer et al. 2003). We also hypothesized that ATD would be associated with differences in ratings for attractiveness and valence for emotional faces (happy, angry and sad). Further, we hypothesized that ATD would be associated with differences in reaction times following the presentation of negative, but not neutral, masked stimuli. Finally, we hypothesized that ATD would be associated with increased accuracy and confidence (or ‘breakthrough’) for identification of negative but not neutral masked images.

Materials and methods

Participants

Twenty healthy female volunteers were recruited by email advertisement. The study was approved by a local ethics committee within the National Research Ethics Service. Participants had been free from psychotropic medication for at least 6 months, were not pregnant, and none declared a personal or family history of major depression or any other axis-I psychiatric disorder, as assessed by the a structured interview drawn from appropriate screening items from the structured clinical interview for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III-R (DSM-III-R; American Psychiatric Association 1994; Spitzer et al. 1992). In addition, participants completed a self-report health questionnaire including questions on psychiatric disorders (Body Perception Questionnaire; Porges 1993) and were interviewed by one of the three authors who are psychiatrists. All volunteers gave written informed consent before participating and were financially compensated. One person vomited after ingesting the drink and did not take part in the study. Four people did not return for the second session, leaving 15 female volunteers (mean age 23.4 years, range 19 to 34) whose data were included in the analysis.

Tryptophan depletion protocol

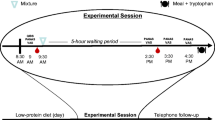

Participants attended the lab on two occasions, representing tryptophan depletion or the control states in a balanced order, cross-over, randomized manner. The two sessions were separated by 9 days on average (range 7–14 days). All participants were tested in the follicular phase of their menstrual cycle. Tryptophan depletion was induced by standard method for women (Ellenbogen et al. 1996), using a nutritionally balanced amino acid mixture containing: l-alanine (4.58 g), l-arginine (4.08 g), l-cysteine (2.25 g), glycine (2.25 g), l-histidine (2.67 g), l-isoleucine (6.67 g), l-leucine (11.25 g), l-lysine monohydrochloride (9.17 g), l-methionine (2.5 g), l-phenylalanine (4.75 g), l-proline (10.17 g), l-serine (5.75 g), l-threonine (5.42 g), l-tyrosine (5.75 g) and l-valine (7.42 g). The control mixture additionally contained tryptophan (1.92 g). The mixture was suspended in 300 ml of tap water and blackcurrant flavour added (SHS International). Participants arrived at the lab at 9 am, baseline blood was taken and participants then drank the mixture at 9:15 am. Blood samples were retaken 4 h later, in order to ensure a stable reduction in tryptophan levels. Participants then completed the cognitive assessment. Blood samples were allowed to clot, centrifuged at 3,000 rpm at 4°C, for 10 min and stored at −80°C. Total serum tryptophan was determined by fluorimetry.

Tasks

Images were presented centrally in a 400 × 400 pixel array on a 19″ LCD screen, in a dark, quiet experimental room. A desktop computer was used to present the tasks and log the behavioural responses, via a programme written on a Matlab platform (Mathwork, Nantick MA). Two further sessions of a separate study followed, which are not reported here.

The face processing task (see Fig. 1) was based on a task previously described (Harrison et al. 2007). In brief, the stimuli were colour photographs of angry, happy and sad faces of 10 male and 10 female identities. Brightness, contrast and luminosity were consistent across each face and emotional expression. Images of faces were shown in random order with each facial identity and emotion combination shown once. Ratings were obtained sequentially for emotional intensity/arousal, valence (negativity/positivity) and attractiveness, for each face and emotion combination. Images remained on the screen until each of the dimensions had been rated. Ratings were inputted using a mouse-controlled cursor on a visual analogue scale displayed on the screen. Ratings for attractiveness and intensity/arousal were constrained within the range 0 to 100, and for valence within the range −100 to 100. This was a self-paced task and participants took approximately 25 min on average to complete it.

In our second task (see Fig. 2) we explored unconscious emotional processing by presenting target images very briefly and backward masking them with other images (masks). We generated a series of pictures to be used respectively as masked pictures or masks. These images were pictures taken from the International Affective Picture Set (IAPS; Lang et al. 2008) a set of affectively salient photographic images widely used in experimental research. In brief, the stimuli were colour photographs of emotionally neutral scenes (such as a car or a field), or emotionally aversive scenes (such as a severe facial deformity or a surgical scene). Masks and masked pictures covered the full screen. Images were shown in random order with each scene shown once. Masks and target images both had a 50% probability of being either aversive or neutral. Participants undertook two tasks both of which comprised a precisely timed sequence. Thirty masked images were presented for 26 ms (two screen refreshes) and masks were presented for 1,000 ms, immediately following each masked image. Participants were then asked to make incidental judgements about whether the scene they had seen was ‘indoors’ or ‘outdoors’. This task was novel, however our backward masking methodology is well established. In our task target images were presented for 26 ms, whereas significant learning effects have been reported for visual target durations as low as 10 ms (Zhang et al. 2009). Following the completion of this task, participants were asked whether or not they had noticed that images had been presented very briefly before each mask. Participants took approximately 7 min to complete the masking task.

In an extension of this masking task, it was explained to participants that each picture they had seen in the previous experimental run had been preceded by a very brief presentation of another picture, some of which were neutral and some of which were aversive. Participants then underwent a further 26 trials, using different pictures but a similar masking method as in task 2, and were also asked to make the same incidental judgement of ‘indoors’ or ‘outdoors’. As for the first masking task, masks and target images both had a 50% probability of being either aversive or neutral. After each trial they were then presented with two pictures presented side by side and given a forced choice of which had been presented before the mask. For each trial participants then rated their confidence that their choice had been correct, from 0 to 10. Participants took approximately 9 min to complete this task.

Subjective rating scales

Before and after each session participants completed a number of questionnaires. We quantified mood state with the Positive Affect Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988), subjective anxiety levels using the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI; The Psychological Corporation) and levels of depression using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; The Psychological Corporation). Drowsiness and dizziness were also measured on a seven point Likert scale.

Physiological recording and analysis

Physiological measurements were recorded for each participant and for each trial. Heart rate (HR) and beat-to-beat arterial pressure were recorded at the finger using a Finometer (Finapres Medical Systems BV, Arnhem, The Netherlands). We calculated heart rate variability (HRV) for the whole length of each session. Skin conductance responses (SCRs) were recorded from two Ag/AgCl electrodes applied to the palmar surfaces of the participants’ second and fourth fingers of the non-dominant hand.

Physiological measurements and event markers were recorded at 100 Hz via an analogue-to-digital converter (CED-Power1401) using the software Spike2 (v5; Cambridge Electronic Design). The arterial pressure signal was pre-processed with an algorithm which identified waveform peaks, yielding systolic blood pressure (SBP) and inter-beat interval (IBI). Baseline IBI and SBP were calculated for the 1,000 ms time interval preceding the presentation of each image. Changes in SBP and IBI were computed with respect to baseline. First we calculated IBI and SBP for the first 4 beats after baseline (i.e. beats 1, 2, 3 and 4), then we interpolated the SBP and IBI data for the first 4 s time points after baseline (i.e. seconds 1, 2, 3 and 4). We tested main effects of ATD on physiological measures, separately for faces of different valence, using paired-samples t tests for seconds 1, 2, 3 and 4 for cardiac physiology and for points of maximal difference for SCRs.

Statistical analysis

Repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to assess main effects of ATD on mood ratings (PANAS, BAI and BDI). Further repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to assess main effects of ATD and face emotion type (angry, happy, sad) on behavioural ratings (attractiveness, intensity/arousal and valence), and also interactions between the effect of ATD and emotion type on behavioural ratings. Similarly, for the backward masking task, we used repeated-measures ANOVAs to assess main effects, firstly of ATD and secondly of target image type (aversive or neutral) on reaction times, and also interactions between the effect of ATD and target image type on reaction times. We also used separate repeated-measures t tests to test the effects of ATD on behavioural ratings for faces of different emotion types.

The arterial pressure signal was analysed for relative percentages of high frequency (0.14–4 Hz; HF-HRV) and low frequency (0.03–0.14 Hz; LF-HRV) heart rate variability (HRV). As with previous papers from our lab (Beacher et al. 2009; Gray et al. 2009) HRV measures were assessed via an autoregressive (AR) parametric model for spectrum estimation (HRV analysis tool version 2.0 http://bsamig.uku.fi/index.shtml, Department of Physics, University of Kuopio, Finland).

The SCR signal was low-pass filtered at 0.1 Hz and polynomial detrended. The peak amplitude was determined for the window 2–8 s from baseline. Baseline skin conductance was calculated by averaging the skin conductance level during the 2 s before the presentation of the task. Amplitude of the SCRs was defined as the difference between the time-window peak value and the baseline value.

For the explicit face processing task repeated-measures ANOVAs were used to assess main effects of ATD and face emotion type (angry, happy, sad) on the blood pressure levels and amplitude of the SCRs, and also to assess interactions between the effect of ATD and emotion type on these physiological measures. Similarly, for the backward masking task, we used repeated-measures ANOVAs to assess main effects of ATD and target image type (aversive or neutral) on physiological measures, and also interactions between the effect of ATD and target image type on physiological measures. We also used separate repeated-measures t tests to test the effects of ATD on physiological measures for faces of different emotion types.

The level of statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (two tailed).

Results

Biochemical analysis

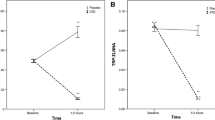

Serum tryptophan levels were reliably reduced by exposure to depleted mixture vs. control (F 1,14 = 155.2, p < 0.001). Mean change in tryptophan levels (±SEM) was −12.4 µg/ml (±0.7) vs. 18.4 µg/ml (±2.3; t = −12.5, p < 0.001) respectively. These changes are consistent with previous reports (Clark et al. 2005; Young et al. 1985). Mean tryptophan levels under ATD were 15.6 µg/ml (±2.9) at baseline and 3.2 µg/ml (±0.92) at 4 h, and for the control condition were 13.2 µg/ml (±1.1) at baseline and 31.7 µg/ml (±8.2) at 4 h.

Questionnaire measures

There were no significant main effects, or trends to main effects, of ATD on mood state, as measured by the PANAS, BAI or BDI after 4 h (see Table 1). Similarly, we found no significant order effects on measures of mood state, or interactions between order and condition. Also, all participants stated that they had no knowledge of which treatment they had received.

Overall peripheral physiology

Additionally, there were no significant main effects of ATD on the heart rate variability (HRV) indices recorded across the entire experimental session. Mean parasympathetic power (high frequency) was 32.9% (14.0%) under ATD and 32.9% (13.1%) under the control condition. Mean sympathetic power (low frequency) was 36.4% (9.1%) under ATD and 37.6% (7.2%) under the control condition. The mean ratio of low to high frequency power was 0.30 (0.22) under ATD and 0.39 (0.25) under the control condition. There were no outliers in the HRV data.

Tasks

Explicit face processing task

Behavioural results

As expected, there were highly significant main effects of emotion type on subjective ratings for attractiveness (F 1,14 = 23.6, p < 0.001), intensity (F 1,14 = 28.0, p < 0.001) and valence (F 1,14 = 161, p < 0.001).

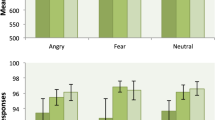

For a summary of effects of ATD on behavioural ratings of faces see Table 2. Main effects of ATD on overall behavioural ratings did not reach statistical significance, however there was a trend for a main effects of ATD on overall valence ratings (F 1,14 = 3.4, p = 0.09), with ATD being associated with lower overall ratings for valence. We examined interactions between ATD and emotion type for behavioural ratings. There was a significant interaction between ATD and emotion type for attractiveness ratings (F 1,14 = 4.0, p = 0.046) but not for intensity/arousal or valence ratings. To explore these effects further, we tested effects of ATD separately on mean behavioural ratings for each emotion type (angry, happy and sad), using separate paired sample t tests. There was a significant effect of ATD on mean attractiveness ratings for happy faces, but not angry or sad faces, with ATD being associated with lower attractiveness ratings (t = −2.5, p = 0.02; 4.6%; see Fig. 2). Also, there was a significant effect of ATD on intensity/arousal ratings for angry faces, but not happy or sad faces, with ATD associated with lower intensity/arousal ratings (t = −2.6, p = 0.02; 4.3% difference; see Fig. 1). Ten of the fifteen participants showed decreases in mean intensity/arousal ratings for angry faces under ATD compared to the control condition. There were no significant effects of ATD on mean ratings for valence for either angry, happy or sad faces considered separately.

Peripheral physiology

There were no significant main effects of ATD on overall evoked change in SBP or IBI in response to faces of any emotion type. However, there were significant main effects of emotion type on evoked change in SBP for second 1 (F 1,14 = 5.7, p = 0.02) and second 2 (F 1,14 = 5.9, p = 0.02), with angry faces being associated with decreases in SBP relative to happy and sad faces. There were no significant main effects of emotion type on evoked change in IBI. There was also no significant interaction between ATD and the effect of emotion type on evoked change in SBP or IBI for any time point.

Further, there were no significant main effects of ATD on evoked change in SCRs, for faces of any emotion type. There was a significant main effect of emotion type on evoked change in SCRs (F 1,14 = 3.5, p = 0.04), with happy faces being associated with smaller decreases in SCRs, relative to happy and sad faces. There was no significant interaction between ATD and the effect of emotion type on SCRs.

Thus ATD did not significantly affect overall behavioural ratings, but ATD was associated with two specific effects: significantly lower intensity/arousal ratings for angry faces and significantly lower attractiveness ratings for happy faces (Figs. 3 and 4).

There was no significant correlation between changes in intensity ratings for angry faces and changes in attractiveness ratings for happy faces (r = 0.35; p = 0.20). We found no significant order effects, or trends for order effects.

Backward masking task

Behavioural results

There was no significant main effect of event type (aversive or neutral target) on reaction times. There was a significant main effect of ATD on overall reaction times, with ATD being associated with reduced reaction times (t = −2.8, p = 0.01; 31% difference). Mean reaction time under ATD was 961 ms (SD = 458 ms) and under the control condition was 1,257 ms (SD = 669 ms). There was no significant interaction between ATD and event type on reaction times. On completion of the first masking task, thirteen of the fifteen participants (87%) answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Did you notice any pictures being flashed BEFORE the main pictures?’.

In the second ‘identification’ masking task, all but one of the participants had an overall accuracy (averaging over both conditions) which was above chance, and in six of the fifteen participants (40%) this was significantly above chance. However, in only one of the fifteen participants there was a significant positive correlation between overall accuracy and overall confidence, over all trials. This suggests that perception of masked pictures involved a measurable degree of conscious awareness for this one participant, but not for other participants. Thus, we provide evidence that that the first masking task (which used the same masking procedure) successfully induced learning of masked target images and also (due to the lack of significant correlation between accuracy and confidence) that the perception of the masked target images was not conscious.

There were no significant main effects of ATD on accuracy or confidence for judgment of masked stimuli, for either aversive-neutral or neutral-neutral trials. However, there was a trend for an ATD-related decrease in overall confidence rating for judgments of aversive-neutral trials (t = −2.1, p = 0.08). There were no significant main effects of event type, or significant interaction between ATD and event type, on accuracy or confidence. For both ATD and control conditions there were no significant correlations between reaction times, accuracy and confidence.

Peripheral physiology

For the backward masking task, there were no significant main effects of event type (aversive or neutral target) or ATD on evoked SBP or IBI, for any time point. Further, there were no significant interactions between ATD and event type on evoked SBP or IBI.

Order effects

One shortcoming of a within-subject design is that practice effects pose a potential confound. To address this potential problem, we tested whether there were significant main effects of ATD order on relevant factors. For the face task these were overall ratings for attractiveness, intensity/arousal and valence, and also event-related SBP, IBI and SCRs. For the backward masking task these were reaction times, accuracy, confidence and event-related SBP and IBI. We found no significant order effects, or trends for order effects.

Discussion

We found that ATD was not associated with a general negative cognitive bias: ATD was not associated with significant overall differences in ratings for faces in terms of attractiveness or positivity/negativity. Also, we did not find that ATD was associated with decreases in mood state. Some prior reports have reported that ATD leads to mood lowering IN HEALTHY SUBJECTS, however, considering the literature as a whole, these effects are either modest or non-significant (Bell et al. 2005), therefore this finding is consistent with the literature. However, as predicted, we found specific modulatory effects of ATD on emotion processing. ATD elicited significantly lower intensity/arousal ratings for angry (but not happy or sad) faces, although the magnitude of this effect was modest (4.3%). We also found that ATD diminished attractiveness ratings for positive happy faces. In the backwards masking task ATD did not affect the unconscious processing of negative, relative to neutral, emotional stimuli. Also, while there was an overall enhancement of psychomotor responsivity (faster reaction times) in this task, there was no enhanced awareness or identification of masked aversive images, suggesting that this was not an effect of perceptual attention. ATD was not associated with overall differences in physiological measurements or difference in evoked physiological responses, following either emotional faces or masked images. In sum, these findings suggest a specific effect of ATD on the conscious appraisal of socially salient information from faces, implicating serotonin in reinforcement of affective engagement to relevant, consciously perceived cues. The effects we report occurred without confounding changes in autonomic or mood state, anxiety level or drowsiness. Our results add to the observations of previous studies which have suggested a role for serotonin in emotional functioning, and dissect specific aspects of cognitive/emotional function which are affected in ATD.

Our finding that ATD was associated with lower intensity/arousal ratings for angry (but not happy or sad) faces extends the suggestion that serotonin has a specific role in the processing of fear and threat (Hellewell et al. 1999). A prior study reported that ATD decreased the declarative recognition of fearful facial expressions (Harmer et al. 2003). Conversely, acute administration of citalopram (a serotonin reuptake inhibitor) and dietary tryptophan is reported to enhance recognition of fearful faces (Attenburrow et al. 2003; Harmer et al. 2002). These categorical effects on expression recognition may be partly dissociated from judgments of perceived emotional intensity, the latter reflecting the impact or salience of the expression on the observer. Here we found that the subjective impact of another’s anger is blunted as a consequence of depleted serotonin level. This observation is not confined to processing threat. Taking attractiveness ratings as a proxy for the willingness approach an individual with a positive expression, again ATD blunted this dimension of social salience. Together these effects on face perception suggest that serotonin enhances conscious evaluation of signals particular to social approach irrespective of valence. Consistent with this is the lack of an effect on sad faces, which intrinsically communicate social disengagement (sensitivity to this is nevertheless related to empathy (Harrison et al. 2006; Harrison et al. 2007)). Differences in facial emotion processing are reported to predict relapse in depressed patients (Bouhuys et al. 1999). One extension of our study would be to examine whether differences in face processing similar to those we report are present in depressed patients, and whether such differences may constitute a significant component of the cognitive substrates of depression. Linking serotonin action specifically to the processing cues for social motivation and interpersonal engagement has broader clinical relevance, for example in schizophrenia. Motivational and social deficits characterize negative schizophrenic symptomatology. Atypical antipsychotics such as clozapine act on serotonergic, as well as dopaminergic, pathways (Leysen et al. 1994) and appear, in contrast to classical neuroleptic medications, to be more effective in treating the negative, as well as the positive, symptoms of schizophrenia. However, this is not firmly established (Salimi et al. 2009) and more knowledge of how antipsychotic blockade of subtypes of serotonin receptors might facilitate the potentially prosocial effects we attribute to serotonin from our ATD study.

The present study is the first, to our knowledge, to explore how serotonergic function relates to the unconscious processing of aversive information. ATD did not increase the detection accuracy of masked aversive images, thus showing that serotonin depletion did not enhance the negative salience (‘attentional grab’) of unconscious visual threat stimuli. ATD was, however, associated with enhanced psychomotor responsivity (faster reaction times) across all stimulus types. This finding is consistent with prior studies that report improvements in focused attention following ATD (Coull et al. 1995; Schmitt et al. 2000), although the overall evidence for such an effect is somewhat inconsistent (Mendelsohn et al. 2009). Our data suggest this effect is operating at the level of volitional ‘conscious’ engagement with the task, rather than at a lower level of peripheral reactivity, since we found no effects of ATD on tonic or reactive autonomic measures that would represent signatures of a somatic state of enhanced motoric and behavioural reactivity.

Masking studies typically assume the binary distinction between conscious and unconscious processing, based on declarative recall but this approach is problematic (Lovibond and Shanks 2002). The threshold of explicit processing is blurred (Wiens 2006) and this is what we address particularly within the perceptual breakthrough (second backward masking) experiment. Together our experiments address the effects of ATD on unconscious processing of affective and neutral stimuli (i.e. masked images not recognized in forced choice), shifts in detection of rapidly presented affective and neutral stimuli (breakthrough) and, in the first experiment, declarative ratings of perceived stimuli. In so doing we feel we can take a view within the limits of experimental design about the role of serotonin in conscious and unconscious processing, suggesting, as above, that observed effects appear to be expressed for explicit, rather than implicit, processes. We acknowledge a potential limitation of our task: We did not find an effect of emotion type (aversive vs. neutral) on reaction times, suggesting that our task may be relatively insensitive to measure implicit processing. We therefore cannot exclude the possibility that serotonin is involved in aspects of unconscious emotional processing but we failed to detect evidence for this.

Ultimately our findings suggest that serotonin may not have a major contribution to unconscious reactions and processing of negative information. It has been proposed theoretically that serotonin has an opponent relationship to dopaminergic signals in behavioural and motivational learning, reflecting long-run average rates of presentation of appetitive stimuli (Daw et al. 2002). While our findings do not contradict this long term model, they suggest an additional short term role in explicit appraisal of motivational salience that is not tied to the valence of stimuli. An important goal of future studies is to extend this experimental work to examine comparatively the effects of dopaminergic and noradrenergic manipulation on social approach/withdrawal in humans.

The absence of an effect of ATD on autonomic responses has implications for understanding and management of biological symptoms of affective disorders. We found that ATD was not associated with differences on overall or evoked cardiovascular or electrodermal response to the presentation of emotional visual stimuli, either emotional faces or masked aversive images. Further, ATD was not associated with differences in tonic autonomic measurements. This implies that the effects we report (including that of reaction time facilitation) are not mediated via the autonomic nervous system. Serotonergic and autonomic functions are related; for example mice that lack serotonin in the central nervous system show decreased blood pressure and heart rate (Alenina et al. 2009). Also, many patients with depression show autonomic dysfunction, for example in lowered heart rate variability (Licht et al. 2008) and increased sympathetic tone (Veith et al. 1994), and similar findings are reported in schizophrenia (Bar et al. 2008). Further, SSRI treatment impacts on vegetative function and autonomic reactivity (Koschke et al. 2009). However, these autonomic changes may be mediated indirectly through other neurotransmitter systems, in particular noradrenergic neurotransmission (Li et al. 2009; Samuels and Szabadi 2008).

In the current study, we did not observe alterations in basal or evoked cardiac response (heart rate or HRV) following ATD. Previous studies also report no effects on resting or background cardiovascular autonomic tone (e.g. van der Veen et al. 2008) but nevertheless show effects of ATD on autonomic reactions to receiving feedback on error trials cognitive tasks. For example, ATD may attenuate cardiac deceleration when informed of errors in time estimation (van der Veen et al. 2008) and flanker tasks (Van der Veen et al. 2009). These suggest diminished cognitive processing of error following ATD (Cools et al. 2008). Direct effects of serotonin on cardiovascular function are suggested in case reported of clinically-significant bradycardia in (atypical) anxiety patients following ATD (Hood et al. 2010), consistent with a serotonergic effect within brainstem baroreflex nuclei (Bago and Dean 2001; Davies et al. 2007). However, we note that our experiments did not embody aspects of monitoring and error-feedback for shaping subsequent task performance and our results suggest that affective processing without these factors does not have a critical serotonin-dependent autonomic component. Also, our female participants had no previous history of clinical anxiety or cardiac dysfunction, and therefore no pathological HR or HRV responses to ATD were observed.

In the current study we did not observe alterations in basal or evoked cardiac response (heart rate or HRV) following ATD. Previous studies also report no effects on resting or background cardiovascular autonomic tone (e.g. van der Veen et al. 2008) but nevertheless show effects of ATD on autonomic reactions to receiving feedback about performance error during cognitive tasks. For example, ATD may attenuate cardiac deceleration associated with errors in time estimation (van der Veen et al. 2008) and flanker tasks (Van der Veen et al. 2009). These suggest diminished processing of negative error information following ATD (Cools et al. 2008). Direct effects of serotonin on cardiovascular function are suggested by case reports of clinically-significant bradycardia in (atypical) anxiety patients following ATD (Hood et al. 2010), and by changes in HRV following SSRI treatment (Licht et al. 2008). These findings are consistent with a serotonergic effect within brainstem baroreflex nuclei (Bago and Dean 2001; Davies et al. 2007). However, in the absence of mood disorder or negative feedback serotonergic modulation does not appear to impact on cardiovascular autonomic control.

Summary

In summary, our results suggest that, within healthy females, acute decreases in serotonin lead to modest specific differences in the processing of emotional facial expressions, and enhanced psychomotor reactivity. We found no evidence that decreases in serotonin affect detection of emotionally aversive and neutral masked images. Our findings help to characterize the role of serotonergic function in emotional processing. Our results complement previous findings suggesting that the effect of serotonin on fear perception is mediated via effect on perceived intensity of facial expressions.

Abbreviations

- ATD:

-

Acute tryptophan depletion

- TRP:

-

Tryptophan

- SCR:

-

Skin conductance response

- PANAS:

-

Positive affect negative affect schedule

- BAI:

-

Beck anxiety inventory

- BDI:

-

Beck depression inventory

- HRV:

-

Heart rate variability

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- IBI:

-

Inter-beat interval

References

Alenina N, Kikic D, Todiras M, Mosienko V, Qadri F, Plehm R, Boye P, Vilianovitch L, Sohr R, Tenner K, Hortnagl H, Bader M (2009) Growth retardation and altered autonomic control in mice lacking brain serotonin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:10332–7

Attenburrow MJ, Williams C, Odontiadis J, Reed A, Powell J, Cowen PJ, Harmer CJ (2003) Acute administration of nutritionally sourced tryptophan increases fear recognition. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 169:104–7

Bago M, Dean C (2001) Sympathoinhibition from ventrolateral periaqueductal gray mediated by 5-HT(1A) receptors in the RVLM. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 280:R976–84

Bar KJ, Greiner W, Jochum T, Friedrich M, Wagner G, Sauer H (2004) The influence of major depression and its treatment on heart rate variability and pupillary light reflex parameters. J Affect Disord 82:245–52

Bar KJ, Wernich K, Boettger S, Cordes J, Boettger MK, Loffler S, Kornischka J, Agelink MW (2008) Relationship between cardiovagal modulation and psychotic state in patients with paranoid schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 157:255–7

Beacher FD, Gray MA, Mathias CJ, Critchley HD (2009) Vulnerability to simple faints is predicted by regional differences in brain anatomy. Neuroimage 47:937–45

Bell CJ, Hood SD, Nutt DJ (2005) Acute tryptophan depletion. Part II: clinical effects and implications. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 39:565–74

Blier P, Bouchard C (1994) Modulation of 5-HT release in the guinea-pig brain following long-term administration of antidepressant drugs. Br J Pharmacol 113:485–95

Bouhuys AL, Geerts E, Gordijn MC (1999) Depressed patients’ perceptions of facial emotions in depressed and remitted states are associated with relapse: a longitudinal study. J Nerv Ment Dis 187:595–602

Bradley BP, Mogg K, Williams R (1995) Implicit and explicit memory for emotion-congruent information in clinical depression and anxiety. Behav Res Ther 33:755–70

Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, Taylor A, Craig IW, Harrington H, McClay J, Mill J, Martin J, Braithwaite A, Poulton R (2003) Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science 301:386–9

Clark L, Roiser JP, Cools R, Rubinsztein DC, Sahakian BJ, Robbins TW (2005) Stop signal response inhibition is not modulated by tryptophan depletion or the serotonin transporter polymorphism in healthy volunteers: implications for the 5-HT theory of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 182:570–8

Cools R, Robinson OJ, Sahakian B (2008) Acute tryptophan depletion in healthy volunteers enhances punishment prediction but does not affect reward prediction. Neuropsychopharmacology 33:2291–9

Coull JT, Sahakian BJ, Middleton HC, Young AH, Park SB, McShane RH, Cowen PJ, Robbins TW (1995) Differential effects of clonidine, haloperidol, diazepam and tryptophan depletion on focused attention and attentional search. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 121:222–30

Davies SJ, Lowry CA, Nutt DJ (2007) Panic and hypertension: brothers in arms through 5-HT? J Psychopharmacol 21:563–6

Daw ND, Kakade S, Dayan P (2002) Opponent interactions between serotonin and dopamine. Neural Netw 15:603–16

Ellenbogen MA, Young SN, Dean P, Palmour RM, Benkelfat C (1996) Mood response to acute tryptophan depletion in healthy volunteers: sex differences and temporal stability. Neuropsychopharmacology 15:465–74

Evers EA, van der Veen FM, Jolles J, Deutz NE, Schmitt JA (2006) Acute tryptophan depletion improves performance and modulates the BOLD response during a Stroop task in healthy females. Neuroimage 32:248–55

Gray MA, Rylander K, Harrison NA, Wallin BG, Critchley HD (2009) Following one’s heart: cardiac rhythms gate central initiation of sympathetic reflexes. J Neurosci 29:1817–25

Harmer CJ, Bhagwagar Z, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM (2002) Acute administration of citalopram facilitates memory consolidation in healthy volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 163:106–10

Harmer CJ, Rogers RD, Tunbridge E, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM (2003) Tryptophan depletion decreases the recognition of fear in female volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 167:411–7

Harrison NA, Singer T, Rotshtein P, Dolan RJ, Critchley HD (2006) Pupillary contagion: central mechanisms engaged in sadness processing. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 1:5–17

Harrison NA, Wilson CE, Critchley HD (2007) Processing of observed pupil size modulates perception of sadness and predicts empathy. Emotion 7:724–9

Hellewell JS, Guimaraes FS, Wang M, Deakin JF (1999) Comparison of buspirone with diazepam and fluvoxamine on aversive classical conditioning in humans. J Psychopharmacol 13:122–7

Hood SD, Hince DA, Davies SJ, Argyropoulos S, Robinson H, Potokar J, Nutt DJ (2010) Effects of acute tryptophan depletion in serotonin reuptake inhibitor-remitted patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 208:223–32

Juckel G, Gudlowski Y, Muller D, Ozgurdal S, Brune M, Gallinat J, Frodl T, Witthaus H, Uhl I, Wutzler A, Pogarell O, Mulert C, Hegerl U, Meisenzahl EM (2008) Loudness dependence of the auditory evoked N1/P2 component as an indicator of serotonergic dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia—a replication study. Psychiatry Res 158:79–82

Klaassen T, Riedel WJ, Deutz NE, Van Praag HM (2002) Mood congruent memory bias induced by tryptophan depletion. Psychol Med 32:167–72

Koschke M, Boettger MK, Schulz S, Berger S, Terhaar J, Voss A, Yeragani VK, Bar KJ (2009) Autonomy of autonomic dysfunction in major depression. Psychosom Med 71:852–60

Kouider S, Dehaene S (2007) Levels of processing during non-conscious perception: a critical review of visual masking. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 362:857–75

Lang PJ, Bradley MM, Cuthbert BN (2008) International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. Technical Report A-8. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

Lesch KP, Bengel D, Heils A, Sabol SZ, Greenberg BD, Petri S, Benjamin J, Muller CR, Hamer DH, Murphy DL (1996) Association of anxiety-related traits with a polymorphism in the serotonin transporter gene regulatory region. Science 274:1527–31

Leysen JE, Janssen PM, Megens AA, Schotte A (1994) Risperidone: a novel antipsychotic with balanced serotonin-dopamine antagonism, receptor occupancy profile, and pharmacologic activity. J Clin Psychiatry 55(Suppl):5–12

Li WY, Strang SE, Brown DR, Smith R, Silcox DL, Li SG, Baldridge BR, Nesselroade KP Jr, Randall DC (2010) Atomoxetine changes rat’s HR response to stress from tachycardia to bradycardia via alterations in autonomic function. Auton Neurosci 154:48–53

Licht CM, de Geus EJ, Zitman FG, Hoogendijk WJ, van Dyck R, Penninx BW (2008) Association between major depressive disorder and heart rate variability in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). Arch Gen Psychiatry 65:1358–67

Lovibond PF, Shanks DR (2002) The role of awareness in Pavlovian conditioning: empirical evidence and theoretical implications. J Exp Psychol Anim Behav Process 28:3–26

MacLeod C, Mathews A, Tata P (1986) Attentional bias in emotional disorders. J Abnorm Psychol 95:15–20

Maes M, Meltzer HY (1995) The serotonin hypothesis of major depression. In: Bloom FE, Kupfer DJ (eds) Psychopharmacology: the fourth generation of progress. Raven, New York, pp 933–944

Mendelsohn D, Riedel WJ, Sambeth A (2009) Effects of acute tryptophan depletion on memory, attention and executive functions: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 33:926–52

Nishizawa S, Benkelfat C, Young SN, Leyton M, Mzengeza S, de Montigny C, Blier P, Diksic M (1997) Differences between males and females in rates of serotonin synthesis in human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94:5308–13

Porges SW (1993) Body perception questionnaire. Laboratory of Developmental Assessment, University of Maryland, Baltimore

Salimi K, Jarskog LF, Lieberman JA (2009) Antipsychotic drugs for first-episode schizophrenia: a comparative review. CNS Drugs 23:837–55

Samuels ER, Szabadi E (2008) Functional neuroanatomy of the noradrenergic locus coeruleus: its roles in the regulation of arousal and autonomic function. Part II: physiological and pharmacological manipulations and pathological alterations of locus coeruleus activity in humans. Curr Neuropharmacol 6:254–85

Schmitt JA, Jorissen BL, Sobczak S, van Boxtel MP, Hogervorst E, Deutz NE, Riedel WJ (2000) Tryptophan depletion impairs memory consolidation but improves focussed attention in healthy young volunteers. J Psychopharmacol 14:21–9

Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB (1992) The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: history, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry 49:624–9

Surguladze SA, Young AW, Senior C, Brebion G, Travis MJ, Phillips ML (2004) Recognition accuracy and response bias to happy and sad facial expressions in patients with major depression. Neuropsychology 18:212–8

van der Veen FM, Mies GW, van der Molen MW, Evers EA (2008) Acute tryptophan depletion in healthy males attenuates phasic cardiac slowing but does not affect electro-cortical response to negative feedback. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 199:255–63

Van der Veen F, Evers E, Mies G, Vuurman E, Jolles J (2009) Acute tryptophan depletion selectively attenuates cardiac slowing in an Eriksen flanker task. J Psychopharmacol (in press)

Veith RC, Lewis N, Linares OA, Barnes RF, Raskind MA, Villacres EC, Murburg MM, Ashleigh EA, Castillo S, Peskind ER et al (1994) Sympathetic nervous system activity in major depression. Basal and desipramine-induced alterations in plasma norepinephrine kinetics. Arch Gen Psychiatry 51:411–22

Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A (1988) Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 54:1063–70

Wiens S (2006) Current concerns in visual masking. Emotion 6:675–80

Young SN, Smith SE, Pihl RO, Ervin FR (1985) Tryptophan depletion causes a rapid lowering of mood in normal males. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 87:173–7

Zhang J, Zhu W, Ding X, Zhou C, Hu X, Ma Y (2009) Different masking effects on “hole” and “no-hole” figures. J Vis 9(6):1–14

Acknowledgements

HDC is funded by a programme grant from the Wellcome Trust. We acknowledge the help of Professor Paul Gard and Drs Bruno Golding, Eileen Daly, Annika Jiskoot, David Gregory and Amy Moran.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Beacher, F.D.C.C., Gray, M.A., Minati, L. et al. Acute tryptophan depletion attenuates conscious appraisal of social emotional signals in healthy female volunteers. Psychopharmacology 213, 603–613 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-1897-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-010-1897-5