Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Breakdown of the inner blood–retinal barrier (BRB) is an early event in the pathogenesis of diabetic macular oedema, that eventually leads to vision loss. We have previously shown that diabetes causes an imbalance of nerve growth factor (NGF) isoforms resulting in accumulation of its precursor proNGF and upregulation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), with consequent increases in the activation of Ras homologue gene family, member A (RhoA). We also showed that genetic deletion of p75NTR in diabetes preserved the BRB and prevented inflammatory mediators in retinas. This study aims to examine the therapeutic potential of LM11A-31, a small-molecule p75NTR modulator and proNGF antagonist, in preventing diabetes-induced BRB breakdown. The study also examined the role of p75NTR/RhoA downstream signalling in mediating cell permeability.

Methods

Male C57BL/6 J mice were rendered diabetic using streptozotocin injection. After 2 weeks of diabetes, mice received oral gavage of LM11A-31 (50 mg kg−1 day−1) or saline (NaCl 154 mmol/l) for an additional 4 weeks. BRB breakdown was assessed by extravasation of BSA–AlexaFluor-488. Direct effects of proNGF were examined in human retinal endothelial (HRE) cells in the presence or absence of LM11A-31 or the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632.

Results

Diabetes triggered BRB breakdown and caused significant increases in circulatory and retinal TNF-α and IL-1β levels. These effects coincided with significant decreases in retinal NGF and increases in vascular endothelial growth factor and proNGF expression, as well as activation of RhoA. Interventional modulation of p75NTR activity through treatment of mouse models of diabetes with LM11A-31 significantly mitigated proNGF accumulation and preserved BRB integrity. In HRE cells, treatment with mutant proNGF (10 ng/ml) triggered increased cell permeability with marked reduction of expression of tight junction proteins, zona occludens-1 (ZO-1) and claudin-5, compared with control, independent of inflammatory mediators or cell death. Modulating p75NTR significantly inhibited proNGF-mediated RhoA activation, occludin phosphorylation (at serine 490) and cell permeability. ProNGF induced redistribution of ZO-1 in the cell wall and formation of F-actin stress fibres; these effects were mitigated by LM11A-31.

Conclusions/interpretation

Targeting p75NTR signalling using LM11A-31, an orally bioavailable receptor modulator, may offer an effective, safe and non-invasive therapeutic strategy for treating macular oedema, a major cause of blindness in diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetic retinopathy is a diabetic microvascular complication that threatens sight and ultimately leads to blindness in working-age individuals in the USA [1]. While ~34.6% of individuals with diabetes have a degree of retinopathy, 6.8% are diagnosed with early diabetic macular oedema (DMO) and 7% with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR) [2]. Inflammation and deterioration of the inner blood–retinal barrier (BRB) and capillary leakage have been identified in both DMO and PDR. Current therapies include laser photocoagulation as well as intravitreal injections of corticosteroids and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (reviewed in [1]). However, the invasiveness of the repeated ocular injection, risk of neuronal toxicity and atrophy and increased thromboembolism impose serious limitations [3]. On the other hand, several systemic orally administered drugs failed repeatedly in clinical trials [4,5,6,7]. Hence, there is a need to identify specific targets that are ‘upstream’ of the terminal effectors involved in diabetes-associated visual outcomes.

Our group discovered that diabetes-associated oxidative stress impairs the processing and maturation of nerve growth factor (NGF) resulting in accumulation of its precursor proNGF in individuals with type 1 diabetes [8] and type 2 diabetes [9] as well as in experimental models of diabetes [10, 11]. This proNGF/NGF imbalance coincided with significant increases in the level and cleavage/shedding of the p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR) in vitreous and serum of individuals with diabetic retinopathy [9, 12]. p75NTR, a member of the TNF-α receptor superfamily, can bind to all neurotrophins and has particularly high affinity for proNGF (reviewed in [13]). The p75NTR receptor undergoes γ-secretase intramembrane proteolysis to release its intracellular domain, which can recruit various adaptor proteins to activate multiple pathways including those involved in inflammation, cell motility, degeneration and cell death [13]. Rho GTPases are a subfamily of the Ras superfamily proteins that play a critical role in the regulation of cell motility and migration [14]. We have also shown that diabetes and overexpression of proNGF activate Ras homologue gene family, member A (RhoA) kinase, coinciding with BRB breakdown [8].

We and others showed that the proNGF–p75NTR pathway is upstream of TNF-α and IL-1β production in the retina [10, 15, 16]. These studies have identified that the proinflammatory action of proNGF occurs via activation of p75NTR in retinal glial Muller cells [10, 11, 15,16,17]. Moreover, genetic deletion or silencing of p75NTR prevented diabetes-induced short-term neurodegeneration [18], inflammation and BRB breakdown [10] and long-term effects including formation of occluded acellular capillaries and pericyte loss [11, 19]. While these findings provide a solid rationale for therapeutic targeting of p75NTR, the studies utilised molecular tools. Therefore, there is a pressing need to develop and test specific p75NTR pharmacological modulators that could be formulated into a viable pharmaceutical option.

The aim of this study is to examine the impact of systemic administration of LM11A-31, a water-soluble, non-peptide, small-molecule p75NTR modulator [20] with high blood–brain barrier permeability [21], on the vascular integrity of the retina in diabetes. LM11A-31 functions as a p75NTR modulator by downregulating p75NTR degenerative signalling in the absence of the proNGF ligand [22]. In the presence of proNGF, it functions as an antagonist to block proNGF binding and activation of p75NTR degenerative signalling [23]. Markers of inflammation, the ratio of NGF/proNGF, and retinal vascular permeability were assessed in a mouse model of diabetes wherein mice were treated with LM11A-31 or vehicle. These in vivo studies were complemented with in vitro studies that examined, for the first time, the extent and the molecular mechanism by which proNGF alters retinal barrier function and contributes to retinal vascular permeability.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were performed in accordance with the Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research, and the Charlie Norwood VA Medical Center Animal Care and Use Committee (ACORP no. 16–01–088).

Induction of diabetes

Male 8-week-old C57BL/6 J mice (~25 g) were purchased from Jackson laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and kept under controlled temperature (21–23°C) and lighting conditions (12 h light/12 h dark cycle). Animals were provided with access to food and water ad libitum. Mice were blindly coded and randomly assigned into four groups: two control groups, receiving either vehicle (saline [NaCl 154 mmol/l]) or LM11A-31 (2-amino-3-methyl-pentanoic acid [2-morpholin-4-yl-ethyl]-amide) and two diabetic groups receiving either vehicle or LM11A-31. Mice were rendered diabetic by five consecutive intraperitoneal injections of streptozotocin, 50 mg/kg (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) in 10 mmol/l citrate buffer. Blood glucose levels were assessed and hyperglycaemia was defined by glucose >12.5 mmol/l. Two weeks after the confirmation of diabetes, one set of control and diabetic mice received non-peptide, small-molecule LM11A-31 (50 mg/kg per mouse) or vehicle (saline) every 48 h by oral gavage for 4 weeks. Experiments were carried out in duplication on each of the four animal sets and body weight was recorded weekly. Mice were killed after 6 weeks of diabetes, eyes were enucleated and microvasculature was isolated from pial blood vessels as described previously [24].

Measurement of serum IL-1β and TNF-α levels

Serum levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were determined using a high sensitivity ELISA kit (catalogue no. 50-112-9749 for IL-1β) and (catalogue no. 50-112-8954 for TNF-α) from eBioscience (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to manufacturer instructions and as described previously by our group [25]. Inflammatory mediators were expressed as pg/ml and normalised to protein concentration in each sample.

Vascular permeability

To determine BRB breakdown, mice received injections of 100 μl of 5 mg/ml BSA-conjugated AlexaFluor-488 green fluoresce (Invitrogen; Thermo-Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) into the jugular vein. After 20 min, mice were killed. Retinas were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and blood was collected from the abdominal inferior vena cava. Fluorescence of retinal lysate and serum from the same mouse was measured using a plate reader (Synergy2; BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) at excitation 490 nm and emission 525 nm. The average retinal fluorescence intensity was normalised to protein content and to serum fluorescence intensity for each mouse, as described previously [10].

Human retinal endothelial cell culture

Human retinal endothelial (HRE) cells and supplies were purchased from Cell Systems Corporations (Kirkland, WA, USA) and VEC Technology (Rensselaer, NY, USA). Experiments were performed using cells between passages 4 and 6, at 37°C, in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. The authentication of HRE and confirmation of mycoplasma-free status were provided by Cell Systems. Cells were randomised and switched to serum-free medium containing 10% MCDB131 complete medium (VEC Technology, Rensselaer, NY, USA) overnight, prior to treatment with cleavage-resistant human mutant proNGF (10 ng, hm-proNGF; Alomone, Jerusalem, Israel) in the presence or absence of the p75NTR modulator LM11A-31 (200 nmol/l) or the Rho kinase inhibitor Y-26732 (10 μmol/l). Cell cultures were run in duplicate for each condition and each experiment was repeated at least three times.

Cell permeability assay

HRE cells grown to confluence on Transwell inserts (Corning, NY, USA) were switched to serum-free culture media. Transport assays were performed using 70 kDa fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–dextran to mimic paracellular flux of an albumin-sized molecule, according to a previously described protocol [26]. FITC–dextran (1 mg/ml) was added to the luminal compartment after which 50 μl samples were collected from abluminal compartment every 60 min. Cell permeability was proportional to the rate of accumulation of FITC–dextran in the abluminal compartment. The rate of flux was calculated over the 4 h time course using the following formula:

where Po is the rate of flux in cm/s, FL is basolateral fluorescence, FA is apical fluorescence, Δt is change in time, A is surface area of the filter and VA is volume of the basolateral chamber [26].

Viability of HRE cells was determined by incubating cells for 4 h at 37°C with 5 mg/ml 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) in PBS. MTT, a yellow dye, is reduced to purple formazan in living cells. MTT was dissolved in acid isopropanol (1:9 of 1 mmol/l HCl/isopropanol). Absorbance was measured at 540 nm and 690 nm using a microplate reader (Bio-Tek), as described previously [18].

G-LISA assay for Rac-1 and RhoA in cell culture and microvascular preparations

Detection of the activity of RhoA-GTPase (catalogue no. BK121) and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1; catalogue no. BK126) was performed using a G-LISA kit from Cytoskeleton (Denver, CO, USA), according to the manufacture protocol. Tissues were homogenised and protein concentration was determined using the reagents provided in the kit. Bound active RhoA or active Rac1 was detected using a specific antibody and luminescence. The luminescence signal was quantified using a microplate reader (Synergy2; BioTek). RhoA-GTPase or Rac1 activity (relative luminescence units) values were normalised to protein content (mg) and then normalised to the average of the control group.

Western blot assay

Retinal samples were homogenised and 30 μg protein was separated by SDS-PAGE [12]. Antibodies, which are listed in ESM Table 1, were validated by the manufacturer. The primary antibody was detected using horseradish peroxidase-conjugated sheep anti-rabbit or anti-mouse antibody (GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA) and enhanced chemiluminescence (Pierce; Thermo-Fisher Scientific, CA, USA). The films were scanned with FluorChem FC3 (ProteinSimple, San Jose, CA, USA) and band intensity was quantified using Fiji densitometry software version-1 (https://imagej.net/Fiji/Downloads), normalised to internal controls and expressed as relative optical density.

Immunofluorescence

was performed as described previously [19]. HRE cells were fixed with 2% (wt/vol.) paraformaldehyde and incubated with blocking buffer followed by (1:100) zonula occludens-1 (ZO-1) antibody and a secondary antibody conjugated to Texas Red (ESM Table 1). Additional sets of cells were stained with (1:200) Oregon Green 448 phalloidin to detect stress fibre formation. Specimens were covered with Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Micrographs were taken using a fluorescence microscope (Axiovert-200; Carl Zeiss, Thornwood, NY, USA) at ×20 magnification.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± SEM and the data were evaluated for normality and processed for statistical analysis using the unpaired Student’s t test, one-way ANOVA or two-way ANOVA. There was no intentional removal of any outcome measures. The Z-score test was used for the detection of outliers. Bonferroni post-multiple comparisons test was used to assess significant differences among individual groups. Analysis was performed using Graph-Pad prism software, version 6 (https://download.cnet.com/GraphPad-Prism/3000-2053_4-8453.html). Significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Modulation of p75NTR using LM11A-31 did not alter blood glucose level or body weight

As shown in ESM Fig. 1, blood glucose levels were significantly higher in diabetic vs control mice at 6 weeks post-induction of diabetes. There was no significant difference in body weight between the control group and diabetic group. Treatment with LM11A-31 did not affect body weight or blood glucose level in either the control group or in the diabetic group.

Treatment with LM11A-31 restored the NGF/proNGF ratio in retinas from diabetic mice

Our group has previously shown that the diabetic state induces a significant increase in proNGF with a decrease in NGF level [9]. Consistent with this, diabetic mouse retinas showed significant increases in proNGF (Fig. 1a, b) as well as significant decrease in retinal NGF levels (Fig. 1a, c). Consequently, the proNGF/NGF ratio was significantly elevated in retinas from diabetic mice as compared with those from control mice (Fig. 1d). Interventional treatment of diabetic mice with LM11A-31 prevented the further increase in proNGF and preserved NGF level (Fig. 1a–c) and restored the retinal proNGF/NGF ratio (Fig. 1d).

Impact of treatment with LM11A-31 on the proNGF/NGF ratio in the retinas of a mouse model of diabetes. (a) Representative western blots of proNGF and NGF. (b) Diabetes significantly increased proNGF expression in mouse retinal lysates vs controls (n = 5). Interventional treatment with LM11A-31 for 4 weeks significantly reduced diabetes-induced increases in proNGF expression. (c) Diabetes decreased NGF expression as compared with control groups (n = 4–5). NGF expression was restored by LM11A-31 treatment. (d) Diabetes significantly increased the proNGF/NGF ratio in mouse retinal lysates vs controls. The proNGF/NGF ratio was restored by LM11A-31 treatment (n = 4). *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA. Cont, control mice; C+LM, control mice treated with LM11A-31; Diab, diabetic mice; D+LM, diabetic mice treated with LM11A-31

Treatment with LM11A-31 mitigated diabetes-induced systemic and retinal inflammation

Diabetes is perceived as a low-grade chronic systemic inflammation [27]. Therefore, we examined expression of inflammatory mediators in the mouse retina and serum. Diabetes significantly increased expression of retinal TNF-α (twofold, Fig. 2a) and IL-1β (twofold, Fig. 2b) as compared with control mice. Oral treatment of diabetic mice with LM11A-31 significantly attenuated diabetes-induced increases in retinal expression of TNF-α and IL-1β (Fig. 2a, b). Indeed, diabetic mice displayed significantly increased levels of serum TNF-α (5.5-fold, Fig. 2c) and IL-1β (ninefold, Fig. 2d) compared with control mice. Oral treatment with LM11A-31 significantly decreased diabetes-induced increases in serum TNF-α and IL-1β (Fig. 2c, d) but had no effect on levels of these inflammatory mediators in control mice.

Impact of treatment with LM11A-31 on retinal and circulatory inflammation in mice. (a, b) Representative western blot and bar graph showing significant increases in retinal TNF-α (n = 5–6) (a) and IL-1β (n = 4) (b) in the diabetes group vs controls, both of which were significantly reduced by treatment with LM11A-31. (c, d) Diabetes induced a significant increase in serum levels of TNF-α (n = 4–5) (c) and IL-1β (n = 4–6)(d) vs controls, which was ameliorated by treatment with LM11A-31. *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA. Cont, control mice; C+LM, control mice treated with LM11A-31; Diab, diabetic mice; D+LM, diabetic mice treated with LM11A-31

Treatment with LM11A-31 prevents diabetes-induced retinal vascular permeability

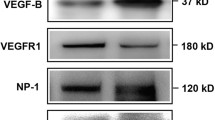

Increases in VEGF have been positively correlated with diabetic retinopathy. Therefore, we examined the impact of modulating p75NTR on VEGF expression. As shown in Fig. 3a, retinal expression of VEGF was significantly increased in diabetic vs control mice. Oral treatment with LM11A-31 led to a significant decrease in retinal VEGF expression in the diabetic mouse (Fig. 3a). Retinal vascular permeability was assessed by extravasation of BSA-conjugated AlexaFluor-488. After 6 weeks of diabetes, there was significant increase in retinal vascular permeability (~twofold) in the retinas from diabetic mice, as compared with control mouse retinas (Fig. 3b). Oral treatment with LM11A-31 significantly decreased the diabetes-induced increase in vascular permeability compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 3b). These results support a pivotal role for upregulated proNGF/p75NTR in mediating diabetes-induced retinal inflammation and vascular permeability.

Impact of treatment with LM11A-31 on mouse retinal VEGF expression and vascular permeability. (a) Representative western blot and bar graph showing a significant increase in retinal VEGF expression in diabetic mice vs controls. This effect was abolished by treatment with LM11A-31 (n = 5–6). (b) Retinal vascular permeability was assessed by extravasation of BSA–AlexaFluor-488 after 6 weeks of streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Fluorescence was measured in retinal lysates and normalised to protein content (mg) and fluorescence intensity in serum samples from the same mouse. Diabetes induced a significant increase (~twofold) in retinal vascular permeability vs controls and this was significantly attenuated by treatment with LM11A-31 (n = 6). *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA, Cont, control mice; C+LM, control mice treated with LM11A-31; Diab, diabetic mice; D+LM, diabetic mice treated with LM11A-31

ProNGF triggers barrier dysfunction independent of inflammation or cell death in HRE cells

To examine whether proNGF causes barrier dysfunction via direct activation of endothelial p75NTR, HRE cells were treated with hm-proNGF, which is cleavage-resistant. For cell permeability assays, HRE cells were grown on Transwell inserts to complete confluence then switched to serum-free medium and challenged with various concentrations of hm-proNGF (1, 10, 20, 50 ng/ml). Treatment of HRE cultures with hm-proNGF induced cell permeability and barrier dysfunction in a bell-shaped manner, where 10 ng/ml caused the highest cell permeability when compared with cells treated with 1 ng/ml, 50 ng/ml or untreated control (Fig. 4a). The viability of HRE cells was examined using the MTT assay using similar doses of hm-proNGF that were used in permeability assay. The results showed that hm-proNGF, up to 50 ng/ml, did not affect viability of HRE compared with untreated controls (Fig. 4b). Because proNGF is a known upstream inducer of inflammatory mediators in vivo [13], we next examined its proinflammatory effect in HRE cells. Treatment with hm-proNGF did not significantly affect expression of VEGF or TNF-α in HRE cells when compared with untreated controls (Fig. 4c). Yet, within the same time-frame (6 h), hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) significantly decreased expression of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 (~45%) and claudin-5 (~40%) vs untreated cells (Fig. 4d).

ProNGF increased cell permeability in HRE cells independent of inflammation or cell death. HRE cells were grown to confluence on Transwell inserts. FITC–dextran (1 mg/ml) was added to the luminal compartment, and 40 μl samples were removed from the abluminal compartment after 1 h. Permeability is proportional to the rate of accumulation of FITC–dextran in the abluminal compartment. (a) Quantitative analysis demonstrated that 10 ng/ml hm-proNGF induced maximum HRE cell permeability when compared with concentrations of 1, 20 and 50 ng/ml (n = 5–9). Permeability was normalised to control Po = (2.65 ± 0.29) × 10−6 cm/s. *p < 0.05 vs untreated control (0 ng/ml hm-proNGF); †p < 0.05 vs 1 ng/ml and 50 ng/ml hm-proNGF. (b) MTT assay (assessed by relative fluorescence units) showed that treatment with hm-proNGF up to a concentration of 50 ng/ml had no effect on the viability of HRE cells (n = 6). (c) Representative western blot and bar graph of VEGF and TNF-α expression in HRE lysates showing no change upon exposure to 10 ng/ml hm-proNGF (n = 3–6). (d) Representative western blot and bar graph showing expression of tight junction proteins ZO-1 and claudin-5, which were significantly decreased in response to 10 ng/ml hm-proNGF treatment (n = 4), *p < 0.05 vs untreated control, unpaired Student’s t test. Cont, control; EC, endothelial cell

ProNGF induced HRE cell permeability in a p75NTR-dependent manner

A representative graph is shown in Fig. 5a to demonstrate how cell permeability is proportional to the rate of accumulation of FITC–dextran in the abluminal compartment over time up to 4 h. The rate of flux was calculated according to the previously published formula [26] and the results of multiple runs were combined. As shown in Fig. 5b, treatment with hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) significantly induced cell permeability (1.4-fold) compared with untreated control. Prior treatment with LM11A-31 significantly attenuated hm-proNGF-mediated HRE cell permeability but did not affect permeability of untreated control cells (Fig. 5b).

ProNGF increased HRE cell permeability in a p75NTR-dependent manner. HRE cells were grown to confluence on Transwell inserts. FITC–dextran (1 mg/ml) was added to the luminal compartment, after which 40 μl samples were removed from the abluminal compartment each hour. Permeability is proportional to the rate of accumulation of FITC–dextran in the abluminal compartment. (a) Representative time course measurement of fluorescence in the abluminal compartment showing an increase in the presence of hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) over time. This increase was significantly ameliorated (p < 0.05) by modulating the p75NTR receptor using LM-11A31. (b) Bar graph showing a significant increase in endothelial cell permeability upon treatment with hm-proNGF vs control. This hm-proNGF-induced increase was not observed upon treatment with LM-11A31 (n = 5–7). Permeability was normalised to control Po = (2.72 ± 0.25) × 10−6 cm/s . *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA. EC, endothelial cell; LM, LM11A-31; RFU, relative fluorescence units

Diabetes and proNGF cause activation of RhoA kinase in a p75NTR-dependent manner

Next, we examined the effect of modulating p75NTR signalling on RhoA kinase activation in vasculature. Mechanisms through which p75NTR regulates RhoA kinase activation have been characterised previously [28]. Due to sample size limitations, activation of RhoA and RAC-1 were assessed using the G-LISA assay. In microvasculature isolated from diabetic mice, there was significant activation of RAC-1 (ESM Fig. 2) and significant (2.2-fold) increase in active RhoA kinase (Fig. 6a) compared with control mouse microvasculature. Treatment with LM11A-31 blunted the increase in RhoA kinase and RAC-1 activity in the diabetic mice. In vitro, we examined the impact of hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) on the activation of RhoA kinase in HRE cells. In parallel to the diabetic condition, hm-proNGF treatment caused significant (1.4-fold) activation of RhoA compared with control cultures (Fig. 6b). The Rho kinase-activating effect of hm-proNGF was significantly ameliorated by prior treatment with LM11A-31.

Diabetes and proNGF activated RhoA in a p75NTR-dependent manner. (a) G-LISA assay showed that 6 weeks of diabetes significantly increased activity of RhoA kinase in microvascular preparations from streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice compared with control mice (n = 5–8). Modulation of p75NTR using LM11A-31 significantly mitigated the diabetes-induced increase in RhoA kinase activity. (b) G-LISA assay in HRE cells showed that 10 ng/ml hm-proNGF induced a significant increase in active RhoA kinase as compared with controls. Prior treatment with LM11A-31 blocked the effect of hm-proNGF on RhoA kinase activity (n = 4–5). Activity is shown as relative luminescence units normalised to protein content (mg) and then normalised to the average of the control group. *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA

Modulation of RhoA activation improved barrier function in HRE cells

To further investigate the involvement of RhoA activation in proNGF-induced vascular permeability, we modulated RhoA activation using Y-26732 in HRE cells. As shown in Fig. 7a, hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) induced a time-dependent increase in HRE permeability. Compared with untreated controls, treatment with hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) significantly increased cell permeability by 1.3-fold, whilst prior treatment with Y-26732 significantly attenuated hm-proNGF-mediated cell permeability (Fig. 7b). These results support the notion that the p75NTR/RhoA kinase signalling pathway contributes to proNGF-induced vascular permeability.

Inhibition of RhoA kinase preserved barrier function in HRE cells. HRE cells were grown to confluence on Transwell inserts. FITC–dextran (1 mg/ml) was added to the luminal compartment, after which 40 μl samples were removed from the abluminal compartment each hour. Permeability is proportional to the rate of accumulation of FITC–dextran in the abluminal compartment. (a) Representative time course measurement of fluorescence in the abluminal compartment showing significant increase over time (p < 0.05) in the presence of hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml). This effect was significantly ameliorated by inhibition of RhoA kinase using Y-26723. (b) Bar graph showing a significant increase in endothelial cell permeability upon treatment with 10 ng/ml hm-proNGF. Prior treatment with 10 ng/ml Y-26723 significantly decreased the fluorescence in the abluminal compartment vs treatment with hm-proNGF alone and preserved the barrier function of hm-proNGF-treated cells (n = 8–9). Permeability was normalised to control Po = (2.72 ± 0.25) × 10−6 cm/s. *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA. EC, endothelial cell; Y, Y-26723. RFU, relative fluorescence units

ProNGF induced occludin phosphorylation and altered distribution of tight junction proteins in a p75NTR-dependent manner

Next we examined phosphorylation of occludin at serine 490 (p-occludinS490), a perquisite for ubiquitination and degradation of the tight junction proteins. Western blot analysis revealed that treatment of HRE cells with hm-proNGF induced significant activation of p-occludinS490 (1.7-fold) and that this activation was blocked by p75NTR modulation using LM11A-31 (Fig. 8a). Immunofluorescence assays showed that ZO-1, a tight junction-associated protein, was localised mostly in discrete, continuous lines in control untreated HRE cells and was redistributed in a punctate and discontinuous pattern in hm-proNGF-treated cells (white arrows, Fig. 8b). The proNGF-mediated redistribution of ZO-1 was mitigated by LM11A-31 treatment (Fig. 8b). Treatment with hm-proNGF also induced intense F-actin stress fibre formation (white arrows, Fig. 8c) when compared with untreated controls; this effect was also mitigated by treatment with LM11A-31.

ProNGF induced occludin phosphorylation, induced intense F-actin stress fibre formation and altered ZO-1 distribution in HRE cells in a p75NTR-dependent manner. (a) Representative western blot and bar graph of expression of the tight junction protein occludin, showing a significant increase in its phosphorylation at serine 490 upon treatment with hm-proNGF. This increase was not observed in cells pre-treated with LM11A-31 (n = 4–7). (b) Immunocytochemistry revealed that hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) altered the distribution of ZO-1 (red) at the cell wall, forming a dotted-like pattern (white arrows), when compared with control cells. This effect was mitigated by treatment with LM11A-31. (c) hm-proNGF (10 ng/ml) induced formation of intense F-actin (green) stress fibre formation (white arrows) around the nuclei (red, propidium iodide stained), when compared with control untreated cells. Prior treatment with LM11A-31 mitigated hm-proNGF-mediated effects. Images were taken at ×20 magnification (scale bars, 50 μm). *p < 0.05 vs all other groups, two-way ANOVA. LM, LM11A-31; PI, propidium iodide

Discussion

Increases in VEGF levels have been closely associated with breakdown of the inner BRB in DMO and to pathological angiogenic response in PDR. Interestingly, individuals with DMO require multiple and repeated intraocular injections of anti-VEGF therapy while those with PDR benefit from fewer anti-VEGF injections [29]. Therefore, it is conceivable to hypothesise that multiple factors other than VEGF can contribute to vascular permeability in DMO. The current study demonstrated the extent and the possible mechanisms by which the proNGF–p75NTR pathway contributes to diabetes-associated systemic inflammation, upregulated VEGF and retinal vascular permeability (a hallmark of DMO). Moreover, the findings here support a potential novel therapeutic approach based on pharmacological modulation of p75NTR using the orally bioavailable compound LM11A-31 to prevent early features of DMO. LM11A-31 (2-amino-3-methyl-pentanoic acid [2-morpholin-4-yl-ethyl]-amide) is a water-soluble isoleucine derivative. LM11A-31 functions as a ligand with relatively high specificity to p75NTR, as demonstrated by the complete loss of its protective activity in cultures of p75NTR−/− neurons, which lack p75NTR [22, 23]. It has proven effective in slowing or reversing neurodegeneration and impaired cognitive behaviour in animal studies [20, 30, 31]. LM11A-31 reduced neuro-inflammation occurring in a Huntington’s disease mouse model [32] and microglial activation in an Alzheimer’s disease model [33]. At the dose used (50 mg/kg), LM11A-31 has been shown to cross the blood–brain barrier following oral administration [21]. Screening of LM11A-31 binding in a screening CEREP panel to identify alternative target receptors was negative [34]. To date, alternative targets or off-target effects have not been identified. LM11A-31 was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration as an investigational new drug, successfully completed a phase I safety trial in normal young and elderly individuals and is currently undergoing evaluation in a phase 2a exploratory endpoint trial in Alzheimer’s disease (ClinTrials.gov registration no. NCT03069014). While the neuroprotective effects of LM11A-31 have been well documented, we believe that this is the first report in which the vascular protective effects of LM11A-31 in the retina in diabetes have been examined and that demonstrates it properties of preventing early inflammation, mitigating VEGF expression and preventing retinal vascular permeability.

In the current study, 6 weeks of diabetes in mice caused imbalance in NGF homeostasis manifested by significant increases in proNGF and decreases in NGF (Fig. 1). These results lend further support to previous reports showing that diabetes impaired maturation of neurotrophins, as demonstrated by low levels of mature NGF and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in vitreal samples from individuals with PDR [8, 9, 35], as well as in preterm infants who experienced proliferative retinopathy [36]. Treatment of diabetic mice with LM11A-31, a pharmacological modulator of p75NTR, prevented the significant increase in proNGF and restored the balance between NGF and proNGF levels. These results concurred with prior reports showing that deletion of p75NTR prevented diabetes-induced imbalance of the NGF/proNGF ratio [10, 11] and prevented the increase in proNGF in an ischaemic retinopathy model [15, 37]. Moreover, LM11A-31 promoted survival rate of oligodendrocytes and functional recovery after spinal cord injury, in part through blocking proNGF effects and its binding to p75NTR [21]. The mechanisms by which modulation of p75NTR might normalise the NGF/proNGF ratio remain to be established in future studies.

In the retina, Muller cells are the main glia, secreting vasopermeability factors such as VEGF and inflammatory mediators including TNF-α and IL-1β, which can regulate vascular permeability under pathological conditions (reviewed in [38]). Our findings clearly demonstrate that treatment of diabetic animals with LM11A-31 mitigated the increase in inflammatory mediators but did not deplete retinal VEGF expression (Fig. 3). In parallel, findings from the current study showed significant increases in TNF-α and IL-1β in serum and retinas isolated from diabetic animals but not from those treated with LM11A-31. These results lend further support to prior reports showing that diabetes-induced upregulation of proNGF and p75NTR coincided with expression of inflammatory mediators and retinal vascular permeability [9, 10, 15]. The diabetes-associated increase in serum levels of TNF-α and IL-1β is intriguing as it might reflect production of inflammatory mediators by peripheral circulatory cells and/or leakage from affected organs. In support of the notion that p75NTR signalling can contribute to peripheral circulatory inflammation are the findings that LM11A-31 abolished proNGF-induced production of IL-6 in mononuclear cells isolated from individuals with arthritis [39]. Our findings lend further support to prior reports demonstrating the anti-inflammatory benefits of blocking p75NTR activity in reducing the number and infiltration of proinflammatory peripheral monocytes in brain injury in vivo and in vitro [40, 41]. While a growing body of evidence supports the finding that activation of the proNGF–p75NTR pathway is an upstream hub for release of inflammatory mediators, we believe that this is the first study showing that systemic modulation of p75NTR using LM11A-31 prevents diabetes-induced circulatory and retinal inflammation.

The above results highlight the anti-inflammatory role attained by modulating proNGF/p75NTR using LM11A-31 and the resulting barrier-preserving effects achieved in vivo. Nevertheless, whether accumulated glial proNGF can directly trigger p75NTR signalling on endothelial cells causing barrier dysfunction remains unknown. Due to the complex and associative nature of in vivo studies, we switched to an in vitro model utilising HRE cells that were probed with a mutant form of human proNGF that is cleavage resistant. Here, we report for the first time that relatively low levels of proNGF can directly trigger barrier dysfunction in HRE cells and cause significant reductions in expression of tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and claudin-5 vs untreated controls (Fig. 4). Examination of different concentrations of proNGF produced a bell-shaped curve in which escalating concentrations (1, 10 and 20 ng/ml) produced significant barrier disruption while a higher level (50 ng/ml) did not. These results are in agreement with a prior observation suggesting that proNGF at a higher level can bind and activate tropomyosin-related receptor A (TrkA), resulting in a different and almost opposite biological action [42]. These permeability effects were not attributed to decline in cell viability as our results showed no significant differences in cultures treated with escalating levels of proNGF up to 50 ng/ml when compared with control. Next, we evaluated whether proNGF-mediated cell permeability in vitro is associated with inflammation as observed in vivo. Interestingly, proNGF-mediated cell permeability was not associated with significant increases in VEGF or TNF-α expression in HRE cells (Fig. 4). The lack of inflammatory action of proNGF in endothelial cells was in agreement with previous findings [19].

Treatment of HRE cells with LM11A-31 prevented proNGF-mediated cell permeability (Fig. 5), confirming the barrier-preserving function of modulating p75NTR activity that we observed in vivo (Fig. 3). p75NTR signals via intramembrane proteolysis to release its intracellular domain, which can recruit various adaptor proteins including RhoA [13]. The activation of RhoA in response to proNGF/p75NTR has been well documented in neurons [43]. Prior studies demonstrated the mechanisms through which p75NTR regulates RhoA kinase activation [28, 44]. Our results showed that treatment with LM11A-31 reduced activation of RhoA in vivo (induced by 6 weeks of diabetes in mice; Fig. 6a) and in vitro (induced by proNGF in HRE cells; Fig. 6b). In support, modulation of p75NTR using LM11A-31 significantly lowered the amount of GTP-bound RhoA in rat cortical neurons [45]. Moreover, proNGF-mediated cell permeability was attenuated by using Y-26723, a Rho kinase inhibitor (Fig. 7a, b). These results suggest that RhoA is a primary downstream target in vascular permeability observed in response to proNGF or diabetes.

Rho GTPases, particularly RhoA, RAC-1 and CDC42, are implicated in cytoskeleton regulation and cell permeability with the subsequent involvement of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin linked to the actin cytoskeleton (reviewed in [46]). Of note, diabetes triggered activation of RhoA (Fig. 6) and RAC-1 (ESM Fig. 2), an effect that was blocked by treatment with LM11A-31. It has been shown that the Rho kinase-dependent reorganisation and accumulation of actin stress fibres occur along small focal adhesion-like structures located at the centre of endothelial cells. Our results showed that proNGF-mediated cell permeability coincided with decrease in tight junction proteins such as ZO-1 and claudin-5 (Fig. 4) and redistribution of ZO-1 and F-actin microfilaments (Fig. 8). In support, prior studies showed that endothelial permeability involves re-localisation of occludin and scaffold protein ZO-1 at tight junctions and also decreasing expression levels of occludin [46]. We also examined the phosphorylation of occludin at S490, which is required for occludin ubiquitination, endocytosis and endothelial permeability [47, 48]. Treatment of HRE cells with proNGF triggered occludin phosphorylation at serine 490; this was mitigated by pharmacological modulation of p75NTR (Fig. 8), suggesting that p75NTR signalling is a potential underlying player regulating alteration in tight junction proteins and subsequent increased vascular permeability.

In conclusion, the mechanism through which LM11A-31 preserves BRB integrity involves modulation of the upregulated p75NTR–RhoA kinase pathway as well as the control of paracrine effects of increased VEGF and proinflammatory mediators in the retina and circulation.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BRB:

-

Blood–retinal barrier

- DMO:

-

Diabetic macular oedema

- hm-proNGF:

-

Human mutant proNGF

- HRE:

-

Human retinal endothelial (cells)

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- NGF:

-

Nerve growth factor

- PDR:

-

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- P75NTR :

-

p75 neurotrophin receptor

- RAC-1:

-

Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1

- RhoA:

-

Ras homologue gene family, member A

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor

- ZO-1:

-

Zona occludens-1

References

Coucha M, Elshaer SL, Eldahshan WS, Mysona BA, El-Remessy AB (2015) Molecular mechanisms of diabetic retinopathy: potential therapeutic targets. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol 22(2):135–144. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-9233.154386

Safi SZ, Qvist R, Kumar S, Batumalaie K, Ismail IS (2014) Molecular mechanisms of diabetic retinopathy, general preventive strategies, and novel therapeutic targets. Biomed Res Int 2014:801269

Falavarjani KG, Nguyen QD (2013) Adverse events and complications associated with intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: a review of literature. Eye (Lond) 27(7):787–794. https://doi.org/10.1038/eye.2013.107

Sheetz MJ, Aiello LP, Davis MD, Danis R, Bek T, Cunha-Vaz J, Shahri N, Berg PH (2013) The effect of the oral PKC β inhibitor ruboxistaurin on vision loss in two phase 3 studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54(3):1750–1757. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.12-11055

Group SRTR (1990) A randomized trial of sorbinil, an aldose reductase inhibitor, in diabetic retinopathy. Sorbinil Retinopathy Trial Research Group. Arch Ophthalmol 108:1234–1244

Chew EY, Klein ML, Murphy RP, Remaley NA, Ferris FL 3rd (1995) Effects of aspirin on vitreous/preretinal hemorrhage in patients with diabetes mellitus. Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study report no. 20. Arch Ophthalmol 113(1):52–55. https://doi.org/10.1001/archopht.1995.01100010054020

Scott IU, Jackson GR, Quillen DA, Klein R, Liao J, Gardner TW (2014) Effect of doxycycline vs placebo on retinal function and diabetic retinopathy progression in mild to moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy: a randomized proof-of-concept clinical trial. JAMA Ophthalmol 132(9):1137–1142. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.1422

Ali TK, Al-Gayyar MM, Matragoon S et al (2011) Diabetes-induced peroxynitrite impairs the balance of pro-nerve growth factor and nerve growth factor, and causes neurovascular injury. Diabetologia 54(3):657–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1935-1

Mysona BA, Matragoon S, Stephens M et al (2015) Imbalance of the nerve growth factor and its precursor as a potential biomarker for diabetic retinopathy. Biomed Res Int 2015:571456

Mysona BA, Al-Gayyar MM, Matragoon S et al (2013) Modulation of p75NTR prevents diabetes- and proNGF-induced retinal inflammation and blood-retina barrier breakdown in mice and rats. Diabetologia 56(10):2329–2339. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-013-2998-6

Mohamed R, Shanab AY, El Remessy AB (2017) Deletion of the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR prevents diabetes-induced retinal acellular capillaries in streptozotocin-induced mouse diabetic model. J Diabetes Metab Disord Control 4(6):129

Ali TK, Matragoon S, Pillai BA, Liou GI, El-Remessy AB (2008) Peroxynitrite mediates retinal neurodegeneration by inhibiting nerve growth factor survival signaling in experimental and human diabetes. Diabetes 57(4):889–898. https://doi.org/10.2337/db07-1669

Elshaer SL, El-Remessy AB (2017) Implication of the neurotrophin receptor p75NTR in vascular diseases: beyond the eye. Expert Rev Ophthalmol 12(2):149–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/17469899.2017.1269602

Lu Q, Longo FM, Zhou H, Massa SM, Chen YH (2009) Signaling through Rho GTPase pathway as viable drug target. Curr Med Chem 16(11):1355–1365. https://doi.org/10.2174/092986709787846569

Barcelona PF, Sitaras N, Galan A et al (2016) p75NTR and its ligand proNGF activate paracrine mechanisms etiological to the vascular, inflammatory, and neurodegenerative pathologies of diabetic retinopathy. J Neurosci 36(34):8826–8841. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4278-15.2016

Lebrun-Julien F, Bertrand MJ, De Backer O et al (2010) ProNGF induces TNFalpha-dependent death of retinal ganglion cells through a p75NTR non-cell-autonomous signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107(8):3817–3822. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0909276107

Galan A, Barcelona PF, Nedev H, Sarunic MV, Jian Y, Saragovi HU (2017) Subconjunctival delivery of p75NTR antagonists reduces the inflammatory, vascular, and neurodegenerative pathologies of diabetic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 58(7):2852–2862. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.16-20988

Al-Gayyar MM, Matragoon S, Pillai BA, Ali TK, Abdelsaid MA, El-Remessy AB (2011) Epicatechin blocks pro-nerve growth factor (proNGF)-mediated retinal neurodegeneration via inhibition of p75 neurotrophin receptor expression in a rat model of diabetes [corrected]. Diabetologia 54(3):669–680. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-010-1994-3

Shanab AY, Mysona BA, Matragoon S, El-Remessy AB (2015) Silencing p75NTR prevents proNGF-induced endothelial cell death and development of acellular capillaries in rat retina. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev 2:15013. https://doi.org/10.1038/mtm.2015.13

Simmons DA, Knowles JK, Belichenko NP et al (2014) A small molecule p75NTR ligand, LM11A-31, reverses cholinergic neurite dystrophy in Alzheimerʼs disease mouse models with mid- to late-stage disease progression. PLoS One 9(8):e102136. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0102136

Knowles JK, Simmons DA, Nguyen TV et al (2013) Small molecule p75NTR ligand prevents cognitive deficits and neurite degeneration in an Alzheimerʼs mouse model. Neurobiol Aging 34(8):2052–2063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2013.02.015

Massa SM, Xie Y, Yang T et al (2006) Small, nonpeptide p75NTR ligands induce survival signaling and inhibit proNGF-induced death. J Neurosci 26(20):5288–5300. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3547-05.2006

Tep C, Lim TH, Ko PO et al (2013) Oral administration of a small molecule targeted to block proNGF binding to p75 promotes myelin sparing and functional recovery after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 33(2):397–410. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0399-12.2013

Mohamed R, Coucha M, Elshaer SL, Artham S, Lemtalsi T, El-Remessy AB (2018) Inducible overexpression of endothelial proNGF as a mouse model to study microvascular dysfunction. Biochim Biophys Acta 1864(3):746–757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbadis.2017.12.023

Elshaer SL, Mohamed IN, Coucha M et al (2017) Deletion of TXNIP mitigates high-fat diet-impaired angiogenesis and prevents inflammation in a mouse model of critical limb ischemia. Antioxidants 6(3):E47

Keil JM, Liu X, Antonetti DA (2013) Glucocorticoid induction of occludin expression and endothelial barrier requires transcription factor p54 NONO. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54(6):4007–4015. https://doi.org/10.1167/iovs.13-11980

Rakotoarivelo V, Lacraz G, Mayhue M et al (2018) Inflammatory cytokine profiles in visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues of obese patients undergoing bariatric surgery reveal lack of correlation with obesity or diabetes. EBioMedicine 30:237–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.03.004

Yamashita T, Tucker KL, Barde YA (1999) Neurotrophin binding to the p75 receptor modulates Rho activity and axonal outgrowth. Neuron 24(3):585–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81114-9

Arevalo JF, Liu TYA, Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group (2018) Intravitreal bevacizumab in diabetic retinopathy. Recommendations from the Pan-American Collaborative Retina Study Group (PACORES): the 2016 Knobloch Lecture. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol 7:36–39

Longo FM, Yang T, Knowles JK, Xie Y, Moore LA, Massa SM (2007) Small molecule neurotrophin receptor ligands: novel strategies for targeting Alzheimerʼs disease mechanisms. Curr Alzheimer Res 4(5):503–506. https://doi.org/10.2174/156720507783018316

Nguyen TV, Shen L, Vander Griend L et al (2014) Small molecule p75NTR ligands reduce pathological phosphorylation and misfolding of tau, inflammatory changes, cholinergic degeneration, and cognitive deficits in AbetaPP(L/S) transgenic mice. J Alzheimers Dis 42(2):459–483. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-140036

Simmons DA, James ML, Belichenko NP et al (2018) TSPO-PET imaging using [18F]PBR06 is a potential translatable biomarker for treatment response in Huntingtonʼs disease: preclinical evidence with the p75NTR ligand LM11A-31. Hum Mol Genet 27(16):2893–2912. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy202

James ML, Belichenko NP, Shuhendler AJ et al (2017) [18F]GE-180 PET detects reduced microglia activation after LM11A-31 therapy in a mouse model of Alzheimerʼs disease. Theranostics 7(6):1422–1436. https://doi.org/10.7150/thno.17666

Yang T, Knowles JK, Lu Q et al (2008) Small molecule, non-peptide p75NTR ligands inhibit Aβ-induced neurodegeneration and synaptic impairment. PLoS One 3(11):e3604. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0003604

Ola MS, Nawaz MI, El-Asrar AA, Abouammoh M, Alhomida AS (2013) Reduced levels of brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the serum of diabetic retinopathy patients and in the retina of diabetic rats. Cell Mol Neurobiol 33(3):359–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-012-9901-8

Hellgren G, Willett K, Engstrom E et al (2010) Proliferative retinopathy is associated with impaired increase in BDNF and RANTES expression levels after preterm birth. Neonatology 98(4):409–418. https://doi.org/10.1159/000317779

Elshaer SL, El-Remessy AB (2018) Deletion of p75NTR prevents vaso-obliteration and retinal neovascularization via activation of Trk-A receptor in ischemic retinopathy model. Sci Rep 8(1):12490. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-30029-0

Sprague AH, Khalil RA (2009) Inflammatory cytokines in vascular dysfunction and vascular disease. Biochem Pharmacol 78(6):539–552. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2009.04.029

Minnone G, Soligo M, Caiello I et al (2017) ProNGF-p75NTR axis plays a proinflammatory role in inflamed joints: a novel pathogenic mechanism in chronic arthritis. RMD Open 3(2):e000441. https://doi.org/10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000441

Lee S, Mattingly A, Lin A et al (2016) A novel antagonist of p75NTR reduces peripheral expansion and CNS trafficking of pro-inflammatory monocytes and spares function after traumatic brain injury. J Neuroinflammation 13(1):88. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12974-016-0544-4

Xu Z, Shi WH, Xu LB et al (2018) Resident microglia activate before peripheral monocyte infiltration and p75NTR blockade reduces microglial activation and early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. ACS Chem Neurosci 10(1):412–423. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00298

Elshaer SL, Abdelsaid MA, Al-Azayzih A et al (2013) Pronerve growth factor induces angiogenesis via activation of TrkA: possible role in proliferative diabetic retinopathy. J Diabetes Res 2013:432659

Yune TY, Lee JY, Jung GY et al (2007) Minocycline alleviates death of oligodendrocytes by inhibiting pro-nerve growth factor production in microglia after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci 27(29):7751–7761. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1661-07.2007

Lin Z, Tann JY, Goh ET et al (2015) Structural basis of death domain signaling in the p75 neurotrophin receptor. eLife 4:e11692. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.11692

James SE, Burden H, Burgess R et al (2008) Anti-cancer drug induced neurotoxicity and identification of Rho pathway signaling modulators as potential neuroprotectants. Neurotoxicology 29(4):605–612. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2008.04.008

Bates DO (2010) Vascular endothelial growth factors and vascular permeability. Cardiovasc Res 87(2):262–271. https://doi.org/10.1093/cvr/cvq105

Murakami T, Felinski EA, Antonetti DA (2009) Occludin phosphorylation and ubiquitination regulate tight junction trafficking and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced permeability. J Biol Chem 284(31):21036–21046. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.016766

Muthusamy A, Lin CM, Shanmugam S, Lindner HM, Abcouwer SF, Antonetti DA (2014) Ischemia-reperfusion injury induces occludin phosphorylation/ubiquitination and retinal vascular permeability in a VEGFR-2-dependent manner. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 34(3):522–531. https://doi.org/10.1038/jcbfm.2013.230

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to D. Antonetti (Kellogg Eye Center, University of Michigan, MI, USA) for providing the antibody to p-occludinS490. Part of the data was presented as an abstract at the 75th Annual Meeting of the American Diabetes Association in 2015.

Funding

This work was supported by RO-1-EY-022408 (ABE), a pre-doctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association (SLE) and by the Jean Perkins Foundation (FML).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SLE, AA, RM, TL and MC contributed to the design, acquisition and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation and drafting the manuscript. FL contributed to the conceptual design of experiments and to manuscript writing and communication. ABE conceived the idea, contributed to the overall experimental design, data analysis and interpretation and writing and critical revision of the manuscript, as well as manuscript correspondence. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ABE is responsible for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

FML is listed as an inventor on patents relating to LM11A-31, which are assigned to UNC and UCSF, and is eligible for royalties distributed by the assigned universities. FML has a financial interest in PharmatrophiX, a company focused on the development of small-molecule ligands for neurotrophin receptors, which has licensed several of these patents. All other authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with their contribution to this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM

(PDF 124 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elshaer, S.L., Alwhaibi, A., Mohamed, R. et al. Modulation of the p75 neurotrophin receptor using LM11A-31 prevents diabetes-induced retinal vascular permeability in mice via inhibition of inflammation and the RhoA kinase pathway. Diabetologia 62, 1488–1500 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4885-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4885-2