Abstract

The Andean common bean AND 277 has the Co-1 4 and the Phg-1 alleles that confer resistance to 21 and eight races, respectively, of the anthracnose (ANT) and angular leaf spot (ALS) pathogens. Because of its broad resistance spectrum, Co-1 4 is one of the main genes used in ANT resistance breeding. Additionally, Phg-1 is used for resistance to ALS. In this study, we elucidate the inheritance of the resistance of AND 277 to both pathogens using F2 populations from the AND 277 × Rudá and AND 277 × Ouro Negro crosses and F2:3 families from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross. Rudá and Ouro Negro are susceptible to all of the above races of both pathogens. Co-segregation analysis revealed that a single dominant gene in AND 277 confers resistance to races 65, 73, and 2047 of the ANT and to race 63-23 of the ALS pathogens. Co-1 4 and Phg-1 are tightly linked (0.0 cM) on linkage group Pv01. Through synteny mapping between common bean and soybean we also identified two new molecular markers, CV542014450 and TGA1.1570, tagging the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 loci. These markers are linked at 0.7 and 1.3 cM, respectively, from the Co-1 4 /Phg-1 locus in coupling phase. The analysis of allele segregation in the BAT 93/Jalo EEP558 and California Dark Red Kidney/Yolano recombinant populations revealed that CV542014450 and TGA1.1570 segregated in the expected 1:1 ratio. Due to the physical linkage in cis configuration, Co-1 4 and Phg-1 are inherited together and can be monitored indirectly with the CV542014450 and TGA1.1570 markers. These results illustrate the rapid discovery of new markers through synteny mapping. These markers will reduce the time and costs associated with the pyramiding of these two disease resistance genes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is the world’s most important grain legume for direct human consumption. However, several major diseases limit its production. Anthracnose (ANT), caused by Colletotrichum lindemuthianum (Sacc. and Magnus) Briosi and Cavara, and angular leaf spot (ALS), caused by Pseudocercospora griseola (Sacc.) Crous and Braun are the most widespread, recurrent, and devastating diseases of the common bean in Latin America and Africa (Correa-Victoria et al. 1989; Pastor-Corrales and Tu 1989; Wortmann et al. 1998). In recent years, ALS has become one of the most important constraints to bean production in Brazil and Africa (Liebenberg and Pretorius 1997; Aggarwal et al. 2004; Sartorato 2004). Both the ANT and ALS pathogens are seed borne and when infected seeds are planted under environmental conditions favoring these diseases, yield losses caused by the ANT pathogen may be extremely high, up to 100% (Pastor-Corrales and Tu 1989); losses caused by the ALS pathogen can reach 70% (Correa-Victoria et al. 1989).

Use of disease resistance genes is the most practical, cost-effective and environmentally friendly strategy for the control of ANT and ALS. Resistance to various diseases in common bean is conferred mostly by single, dominant genes with race-specific resistance (R-genes) usually associated with a hypersensitive reaction (HR) according to the gene-for-gene concept (Flor 1971, Caixeta et al. 2003, 2005; Kelly and Vallejo 2004).

Resistance to C. lindemuthianum is conditioned by some 13 reported genes identified by the Co symbol (Kelly and Vallejo 2004). All but one of these genes is a single, dominant resistance locus and of these, Co-1, Co-12 and Co-13 belong to the Andean gene pool (Gonçalves-Vidigal et al. 2009). Six independent dominant genes identified by the Phg symbol condition resistance to P. griseola (Carvalho et al. 1998; Caixeta et al. 2003, 2005). Among these genes, only Phg-1, present in bean cultivar AND 277, originated in the Andean gene pool.

Cultivar AND 277 [Cargabello × (Pompadour Checa × Línea 17) × (Línea 17 × Red Kloud)] is an important resistance source used in breeding programs in Brazil and Southern Africa (Carvalho et al. 1998; Aggarwal et al. 2004; Arruda et al. 2008). AND 277 has the Co-1 4 allele (of the Co-1 locus) that confers resistance to C. lindemuthianum races 9, 23, 55, 64, 65, 67, 73, 75, 81, 83, 87, 89, 97, 117, 119, 339, 343, 449, 453, 1033, and 2047 (Alzate-Marin et al. 2003; Arruda et al. 2008). Moreover, the Phg-1 ALS-resistance gene in AND 277 confers resistance to the Brazilian P. griseola races 31-17, 31-39, 61-31, 63-19, 63-23, 63-31, 63-35, and 61-41 (Caixeta et al. 2005). In addition, AND 277 has been reported as ALS resistant under field conditions during 2 years of evaluations in Malawi (Aggarwal et al. 2004).

Eight Co ANT resistance genes, including Co-1, have been mapped onto different linkage groups (LGs) in the consensus linkage map of P. vulgaris (Bean Core Map 2009; Pedrosa-Harand et al. 2008). Co-1 is located on LG Pv01 (Freyre et al. 1998), while of the six ALS resistance genes, only the Phg-2 gene was mapped on LG Pv08. Thus, molecular markers are needed to map the Phg-1 and Co-1 4 disease resistance genes and to utilize these markers as tools for marker-assisted selection.

In common bean, clusters of Co-ANT and Ur-rust resistance genes have been located on LGs Pv01, Pv04, and Pv011 (Geffroy et al. 1999; Miklas et al. 2002, Kelly et al. 2003; Kelly and Vallejo 2004, Miklas et al. 2006; Geffroy et al. 2009). Lopez et al. (2003) identified a set of resistance gene analogs from common bean that were linked with resistance loci to different common bean pathogens and reported potential linkage among quantitative trait loci (QTL) that confer partial resistance to ANT and ALS, but until now, no association has been established between the Co and Phg genes.

The objective of this study was to elucidate the genetic basis of resistance of the Andean bean cultivar AND 277 to the ANT and ALS pathogens via evaluating F2 populations from the crosses AND 277 × Rudá and AND 277 × Ouro Negro, and of F2:3 families from the cross AND 277 × Ouro Negro to test for linkage between the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes. AND 277 is resistant to ANT and ALS while Rudá and Ouro Negro are susceptible to both. In addition, we investigated the utility of the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers for genetic mapping of these two genes.

Materials and methods

Genetic crosses and disease segregation experiments

These studies were conducted in a greenhouse and at the Laboratório de Biotecnologia do Núcleo de Pesquisa Aplicada à Agricultura (Nupagri) of the Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Paraná, Brazil. The genetic co-segregation test for the Co-1 4 and the Phg-1 alleles that confer resistance to ANT and ALS in the Andean cultivar AND 277 was performed in two different experiments. In the first, the common bean cultivar AND 277 (resistant to races 73 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola) was crossed with the Rudá cultivar (of Mesoamerican origin and susceptible to races 73 and 63-23 of the same pathogens). In the second experiment, the cultivar AND 277 cultivar (also resistant to races 65 and 2047 of C. lindemuthianum) was crossed with the cultivar Ouro Negro (of Mesoamerican origin and susceptible to races 65, 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola). In both cases, AND 277 was used as the female parent. The F1 seeds were planted in pots with soil that was previously sterilized and fertilized. Bean plants were kept in a greenhouse until they produced F2 seeds.

A total of 127 F2 seeds from the AND 277 × Rudá cross were sown in soil-containing trays (50 × 30 × 9 cm) at a density of approximately 100 seeds per tray. These plants were inoculated with race 73 of C. lindemuthianum and race 63-23 of P. griseola. A total of 129 F2 plants derived from the cross AND 277 × Ouro Negro were also sown in trays in order to be inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. Another set of F2 seeds from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross were multiplied in pots in order to obtain the 71 plants of the F3 generation. F2:3 families (obtained by selfing individual F2 plants) were used to characterize the corresponding F2 plants for resistance to races 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. The dominant traits inherited from the male parents (violet flower color in the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross and indeterminate growth habit in the AND 277 × Rudá cross) were observed in both F1 generations to ascertain their hybridity. Molecular segregation analyses were conducted in two separate F2 populations from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro crosses; one with 129 F2 plants and the other with 71 F2 plants from which the corresponding 71 F2:3 families were obtained.

Inoculation and disease evaluation of C. lindemuthianum and P. griseola

Races 73 and 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola were selected for the co-segregation analysis. All parental cultivars inoculated with these races produced the expected and known resistant or susceptible reactions. Race 2047 of C. lindemuthianum was provided by Dr. James D. Kelly, Michigan State University. Race 63-23 of P. griseola was donated by BIOAGRO of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa. Races 73 and 2047 of C. lindemuthianum were grown on petri dishes containing Mathur’s medium (Mathur et al. 1950). Identification of races 73 and 2047 was confirmed by their inoculation onto a set of 12 common bean ANT differential cultivars (Pastor-Corrales 1992). The initial inoculum of each of the C. lindemuthianum and P. griseola races was obtained from monosporic cultures. Subsequent inoculum for the ANT pathogen races was produced on young green common bean pod medium incubated at 22°C for 14 days. Inoculum of race 63-23 of the ALS pathogen was first multiplied in petri dishes containing 1–2 mL of a solution of 800 mL of sterilized water, 200 mL of commercial tomato sauce, 15 g agar, 4.5 g of calcium carbonate (CaCO3), and 10 μg mL−1 of streptomycin (Sanglard et al. 2009). Subsequent inoculum of race 63-23 was produced in petri dishes containing tomato medium and maintained in a BOD incubator at 24°C for 15 days. A spore suspension containing 2.0 × 104 conidia mL−1 was utilized to inoculate the plants (Cardenas et al. 1964).

Evaluation of the AND 277 × Rudá F2 population

Each of the 127 F2 individuals from the AND 277 × Rudá cross was inoculated with races 73 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola following published methodology (Cardenas et al. 1964; Pastor-Corrales and Castellanos 1990; Gonçalves-Vidigal et al. 2001). After emergence of the first trifoliate leaf, the right lateral leaflet was inoculated with C. lindemuthianum and the left lateral leaflet with P. griseola. Each pathogen was inoculated using separate small camel’s hair brushes. In order to detect any occurrence of cross-protection, that is the protection conferred on a host by infection with one strain of a pathogen that prevents infection by another strain of the same or a related or different pathogen, the parents used to make the crosses in this study were tested as a control group. The tested cultivars were Rudá (susceptible to races 73 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola) and AND 277 (resistant to both races). Hence, 12 Rudá and 12 AND 277 plants were simultaneously inoculated with races 73 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola following the procedure described above. All Rudá control plants were susceptible while all AND 277 were resistant to races 73 and 63-23. Likewise, 12 Ouro Negro cultivar plants used as a control were inoculated simultaneously with races 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. All Ouro Negro plants were also susceptible to both races. Fifteen plants from the F1 population derived from the AND 277 × Rudá cross were also inoculated with the same races and were all resistant.

Evaluation of the population from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross

For the second cross, AND 277 × Ouro Negro, 15 plants from each of the 71 F2:3 families derived from the F2 population used for molecular analysis were inoculated separately with each pathogen, races 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. This same test was performed in 129 individuals from another F2 population from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross, which were inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. Seedlings were grown under natural light in greenhouses supplemented with 400 W high-pressure sodium lamps, providing a total light intensity of 115 μmoles m−2 s−1, for 7–10 days until they reached the first trifoliate leaf stage. Twelve plants from the parents (Ouro Negro and AND 277), 15 F1 plants, and 15 plants from each of the 71 F2:3 families were inoculated with spore suspensions containing 2.0 × 106 spores ml−1 of race 2047 of C. lindemuthianum, using a De Vilbiss number 15 atomizer powered by an electric air compressor (Schulz, SA, Joinville, Santa Catarina, Brazil). A similar procedure was utilized for the inoculation of race 63-23 of P. griseola. After inoculation, the plants were placed in a mist chamber for 2 days and maintained at >95% relative humidity at 21–23°C for 12 h of daylight (light intensity of 300 μmoles m−2 s−1 at a height of 1 m). Then, the inoculated plants were transferred to benches in a greenhouse with a suitable environment at 22°C and artificial light (12 h of daylight at 25°C) for 7 days. Anthracnose disease reactions were evaluated visually using a scale of 1–9 (Pastor-Corrales et al. 1995). Plants with disease reaction scores between 1 and 3 were considered resistant, whereas plants with scores from 4 to 9 were considered susceptible. The reaction to ALS was estimated by utilizing the symptom scale according to Inglis et al. (1988). The resistance genotype of each F2 plant was inferred based on the genotypes of its F2:3 families.

DNA extraction

The molecular marker analysis was conducted using DNA extracted from the central leaflet of the first trifoliate leaf of 129 F2 individuals from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross inoculated with races 65 of the ANT and 63-23 of the ALS pathogens, respectively. The same molecular analysis was performed in 71 F2 plants from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross inoculated with races 2047 of the ANT and 63-23 of the ALS pathogens, respectively. DNA extraction was performed according to the method described by Afanador et al. (1993), with the following modification: the DNA was extracted from the central leaflet of the first trifoliate leaf utilizing 400 mL of CTAB extraction buffer.

Molecular markers analyses

A total of 33 molecular markers including 26 sequence-tagged sites (STS) and seven microsatellite markers previously mapped to LG Pv01 (Yu et al. 2000; Gaitán-Solís et al. 2002; Blair et al. 2003; McClean et al. 2010; McConnell et al. 2010), were tested on parents, and on resistant and susceptible bulks. Two contrasting DNA bulks (Michelmore et al. 1991) were constructed by pooling equal volumes of fluorometrically standardized DNA from four to six resistant and susceptible individuals, respectively, of the AND 277 × Ouro Negro F2 population. Of these 33 markers, two—CV542014 and TGA1.1—showed contrasting amplification patterns in parental materials and in resistant versus susceptible bulks or individuals (Fig. 1) and were retained for further studies. All amplification reactions were performed with a thermal cycler (MJ Research Inc., Waltham, MA, USA). The PCR cycle consisted of 3 min at 95°C and 35 cycles of 30 s at 92°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 60 s at 72°C followed by a 5 min extension at 72°C and 4°C for 4 min. Polymerase chain reactions (PCRs) were performed in 25 μL total reaction mixture containing 30 ng of total DNA, 0.2 mM of each dNTP, the standard Taq buffer with 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM of forward primer and reverse primer, and 1 unit of Taq DNA polymerase. Following the addition of 2 μL of loading buffer (30% glycerol and 0.25% bromophenol blue), the PCR products from CV542014 were analyzed on 6% polyacrylamide gels stained with ethidium bromide; PCR products from TGA1.1 were visualized on agarose gels. The DNA bands were visualized under ultraviolet light; digital images were recorded by Eagle Eye II (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) and L-PIX Image EX model (Loccus Biotecnologia-Locus do Brasil, Cotia, Sp, Brasil).

Electrophoretic analysis of amplification products of the CV542014 (a) and TGA1.1 (b) markers. Lanes: LAD, Ladder 100 bp; A, AND 277; ON, Ouro Negro; RB, resistant bulk; R, individuals of the resistant bulk; SB, susceptible bulk; S, individuals of the susceptible bulk to Colletotrichum lindemuthianum and Pseudocercospora griseola. The arrow indicates a DNA band of 450 bp (CV542014) and 570 bp (TGA1.1) linked to the resistance locus Co-1 4 /Phg-1. The 6th lane from the left shows a heterozygous member of the resistant bulk (a); the presence of the resistance phenotype in this heterozygote is consistent with the dominant nature of the resistance phenotype

Molecular mapping

Markers CV542014 and TGA1.1 were mapped in the California Dark Red Kidney/Yolano (CY: 111 lines; Johnson and Gepts 2002) and BAT 93/Jalo EEP 558 (BJ: 71 lines; Freyre et al. 1998) recombinant inbred mapping populations, as well as in the the F2 generation of the cross AND 227 × Ouro Negro. The primer sequences used for the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers were ‘CACTTTCCACTGACGGATTTGAACC’ (forward) and ‘GCACAAGGACAAGTGGTCTGG’ (reverse) and ‘CAGAGGATGCTTCTCACGGT’ (forward) and ‘AAGCCATGGATCCCATTTG’ (reverse), respectively, (McConnell et al. 2010, available from the PhaseolusGenes database: http://phaseolusgenes.bioinformatics.ucdavis.edu/markers/?ALL=CV542014&format=html and http://phaseolusgenes.bioinformatics.ucdavis.edu/markers/?ALL=TGA1.1&format=html).

Statistical analyses

Segregation analyses of the disease reaction from 127 F2 plants from AND 277 × Rudá cross and 129 F2 plants from AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross were performed by the chi-square (χ2) test, according to a Mendelian segregation hypothesis of 3 (R_ (resistant) to 1 rr (susceptible). This test was also performed with the data of 71 F2:3 families from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross, according to a segregation hypothesis of 1:2:1 (RR:Rr:rr). A goodness-of-fit test for a 1:1 segregation ratio was performed for the CV542014 and TGA1.1 marker segregations in the BJ and CY RIL populations. Linkage analyses were performed using the computer software MAPMAKER/EXP 3.0 (Lincoln and Lander 1993) to estimate genetic distances between the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers and the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes in two separate F2 populations derived from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross. A minimum likelihood of the odds ratio score (LOD) ≥3.0 and a maximum distance of 30 centiMorgans (cM) were used to test linkages among these markers, as described by Freyre et al. (1998). The LG containing the Co-1/Phg-1 locus and the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers were labeled and oriented according to the most recent standardization of the common bean linkage map nomenclature (Pedrosa-Harand et al. 2008).

Results

Genetic resistance showing monogenic co-segregation of the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes

The segregation observed in the 127 F2 plant population derived from the AND 277 × Rudá cross, inoculated with races 73 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola, showed co-segregation of 95 individuals resistant to and 32 individuals susceptible to both pathogens (P = 0.96 for a 3R:1S expected ratio for a single dominant gene) (Table 1). This segregation data confirmed the monogenic resistance in the AND 277 cultivar to race 73 of C. lindemuthianum and to race 63-23 of P. griseola, most likely conferred by the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes, respectively, (Alzate-Marin et al. 2003; Carvalho et al. 1998).

Table 2 shows the segregation of 71 families inoculated for resistance to races 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. All individuals within the families co-segregated similarly for resistance/susceptibility to the two pathogens, and no recombinants were observed, revealing the close linkage between the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 alleles. As anticipated, the F2 population fit a 3:1 (resistant: susceptible) ratio (P = 0.79). This segregation pattern agrees with a previous report that Co-1 4 is a single dominant resistance allele (Alzate-Marin et al. 2003). The 71 F2:3 families derived from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross, inoculated with races 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola, segregated into three classes: uniformly resistant (n = 20; inferred F2 genotype: RR), segregating for resistance (n = 33; Rr), and uniformly susceptible (n = 18; rr) resulting in a goodness of fit to a 1:2:1 ratio for a single, dominant gene (P = 0.79). This segregation data corroborated the monogenic resistance in the AND 277 cultivar to race 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and race 63-23 of P. griseola, conferred by the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes, respectively.

Linkage mapping of the Co-1/Phg-1 locus

The strategy used to identify markers linked to Co-1 4 involved 26 sequence-tagged site (McConnell et al. 2010) and seven microsatellites (Yu et al. 2000; Gaitán-Solís et al. 2002; Blair et al. 2003) markers previously mapped on LG Pv01, using the methodology proposed by Michelmore et al. (1991). Of all STS markers tested in this study, only CV542014 and TGA1.1 were polymorphic among parents and R and S bulks. These two markers showed linkage when tested on 129 individuals of the F2 population from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross (Tables 3, 4). Table 3 shows the phenotypic evaluation of these 129 F2 plants from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross, inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola, and the presence or absence of molecular markers CV542014 and TGA1.1 in these plants. The data showed the absence of recombinants among the two disease resistance genes, suggesting a close association between the Co-1 4 ANT and the Phg-1 ALS resistance genes in AND 277. Additionally, Table 3 shows that the F2 population derived from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola, consisted of 96 resistant and 33 susceptible individuals [P = 0.88 (1 df) for a 3R:1S expected ratio for a single dominant gene or two tightly linked genes without recombination].

Genetic mapping of individuals from the two separate F2 populations of the cross AND 277 × Ouro Negro, inoculated, respectively, with races 65 and 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and race 63-23 of P. griseola, revealed the presence of CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers in the resistant plants (Tables 3, 4). The genetic linkage analysis resulted in a segregation of 20 (+):32 (+):19 (−), indicating a good fit to the expected ratio of 1:2:1 (P = 0.70) These results showed that the families, which were inoculated separately with pathogen strains 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola, co-segregated for resistance response to the two pathogens and the two molecular markers.

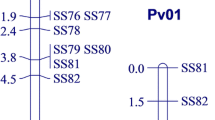

The marker CV542014 revealed linkage when assayed on the parents and the individuals of the resistant and susceptible bulks. Two bands were produced in the genomic region of interest. A larger band (450 bp) was present in AND 277 and the resistant bulk, while a band of 350 bp was present in the susceptible parent Ouro Negro, and the susceptible bulk. Thus, we have scored the segregation of one band only (450 bp) linked in coupling phase to the resistance genes. The CV542014 marker identified by bulked segregant analysis was assayed in two separate F2 populations from the cross AND 277 × Ouro Negro. The linkage analysis confirmed that this marker was linked at a distance of at most 0.7 cM from the Co-1 4 allele (Co-1 locus) and segregated in a 3:1 ratio, indicative of the presence of a dominant marker on Pv01 LG (Fig. 2). Using the primer TGA1.1, a fragment of 570 bp was amplified in all F2 resistant individuals from cross AND 277 × Ouro Negro. No fragment was amplified in susceptible individuals. This dominant marker segregated in a ratio of 3:1 and was linked to the Co-1 4 allele (Co-1 locus) at a distance of 1.3 cM on LG Pv01 (Fig. 2).

Genetic distance and location of the locus Co-1 for resistance to common bean anthracnose, the Phg-1 gene for resistance to angular leaf spot, and the molecular markers (CV542014 and TGA1.1) in the linkage group Pv01 of Phaseolus vulgaris L., using the populations from the crosses AND 277 × Ouro Negro. Map was drawn with MapChart (Voorrips 2002)

The molecular markers CV542014 and TGA1.1 were tested in two separate F2 populations for linkage with the Co-1 4 /Phg-1 genes. The segregation of the BAT 93/Jalo EEP 558 (BJ) RI population assayed with the CV542014 resulted in a ratio of 37 (+): 34 (−) (χ2 = 0.13; p = 0.72 for a goodness-of-fit to a 1:1 ratio). This marker assayed in the California Dark Red Kidney/Yolano (CY) RI population revealed the segregation of the 59 (+): 52 (−) (χ2 = 0.44; p = 0.51 for a 1:1 ratio). In addition, TGA1.1 marker was tested in mapping population CY RI, revealing a ratio of 57 (+): 54 (−) (χ2 = 0.081; p = 0.78 for a 1:1 ratio).

Discussion

The Co-1 4 gene for resistance to the ANT disease of common bean was discovered by Alzate-Marin et al. (2003) by analyzing segregating F2 populations from crosses of the resistant Andean bean cultivar AND 277 with various susceptible cultivars including Ouro Negro. Similarly, the Phg-1 gene, also present in AND 277 and which confers resistance to ALS, was identified by Carvalho et al. (1998) by studying an F2 population from the cross AND 277 × Rudá inoculated with race 63-23 of P. griseola.

In the present study, we reveal the co-segregation of the resistances to ANT and ALS in an F2 population from the AND 277 (R) × Rudá (S) cross-inoculated simultaneously with races 73 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. This co-segregation was also observed in 71 F2:3 families from the cross of AND 277 (R) × Ouro Negro (S) inoculated with race 2047 of C. lindemuthianum and with the same 63-23 race. Each of the 71 F2:3 families had similar responses to the races of C. lindemuthianum and P. griseola. Furthermore, the data indicated a close association between the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes based on the segregation of these families. The observed segregation ratio of 20RR:33Rr:18rr individuals fitted an expected 1RR:2Rr:1rr ratio for a single dominant gene or two tightly linked genes without recombination. The 33 heterozygous families showed monogenic segregations for resistance to races 2047 and 63-23 (P varied from 0.76 to 1.00 for both races). Our results are consistent with those of Alzate-Marin et al. (2003) and Carvalho et al. (1998) showing that resistance to the ANT and ALS pathogens in AND 277 is monogenic and dominant.

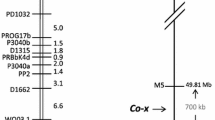

Linkage analysis was performed in 129 plants from the F2 of the cross AND 277 × Ouro Negro inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola. The co-segregation analysis did not reveal recombination between the two genes (Co-1 4 and Phg-1). The molecular test, utilizing the CV542012 marker, was conducted with 129 plants F2 (inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola) and with 71 F2 plants (inoculated with races 2047 and 63-23), both derived from the AND 277 × Ouro Negro cross. Only one recombinant was present in both populations, emphasizing that there is a close association between the CV542012 marker and the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 resistance genes in AND 277. When the molecular marker TGA1.1 was tested in 129 plants from the cross of AND 277 × Ouro Negro inoculated with races 65 of C. lindemuthianum and 63-23 of P. griseola, the linkage analysis showed that TGA1.1 segregated in a 3:1 (P = 0.58) ratio and was linked at a distance of 1.5 cM from the Co-1 locus. The Co-1 locus has previously been mapped to LG Pv01 in the common bean consensus map (Vallejo and Kelly 2002; Kelly et al. 2003). Therefore, the co-segregation among the ANT and ALS resistance genes and the CV542012 molecular marker indicates that they are positioned at the same locus of LG Pv01, which contains a complex cluster of various disease resistance genes (Freyre et al. 1998).

The resistance of AND 277 to ANT was verified by Alzate-Marin et al. (2003) in a study in which AND 277 was inoculated with races 64, 65, 73, 81, 87, 89, 119, and 453 of C. lindemuthianum. After allelism tests using cultivars Ouro Negro (Co-10 gene), Kaboon (Co-1 2) and MDRK (Co-1 gene) (Melotto and Kelly 2000), the gene present in AND 277 was designated as Co-1 4. Nevertheless, Arruda et al. (2008) hypothesized the existence of a second gene (Co-9 gene) conferring resistance to race 73 which segregates in the AND 277 × Rudá cross. In the present study, only a single dominant gene conferring resistance to races 73 and 2047 of C. lindemuthianum was observed. Consequently, the designation of Co-1 4 for the resistance gene present in AND 277 was supported.

The resistance of Co-1 4 to race 2047 and other races of the bean ANT pathogen is enormously valuable. This race infects 11 of the 12 differential bean cultivars used to characterize the races of C. lindemuthianum. This is especially significant because each of the 12 differential cultivars harbor a gene or genes for resistance to the different races of the ANT pathogen. At present, race 2047 has the broadest spectrum of virulence of any known race of C. lindemuthianum. Additionally, the Co-1 4 gene continues to be effective against Middle American races and against the races most frequently found in Brazil (races 65, 73, 81, 89), as well as against 15 other Brazilian races of the bean ANT pathogen. The Andean Co-1 resistance locus has been very valuable in breeding Mesoamerican beans with ANT resistance, particularly in dry bean production countries, such as Brazil, Mexico, and Central American countries, where Mesoamerican races of the ANT pathogen predominate (Pastor-Corrales 1996; Kelly and Vallejo 2004).

Furthermore, the Co-1 locus is uniquely important to breeders developing gene pyramids combining complementary genes from both the Andean and Mesoamerican Phaseolus gene pools. Three markers linked to the Co-1 locus in repulsion phase have been reported, two of them are RAPD markers (Young and Kelly 1997; Gonçalves-Vidigal and Kelly 2006) and one is an AFLP marker (Mendoza et al. 2001). In addition, one co-dominant STS marker, SEACT/MCCA, has been identified as linked to the Co-1 locus (Kelly and Vallejo 2004; Vallejo and Kelly 2008). The Andean Co-1 locus was mapped to LG Pv01 using the SEACT/MCCA marker in the BJ recombinant inbred line (RIL) mapping population (Kelly and Vallejo 2004). Indirect evidence comes from the positioning of two provisionally assigned loci, Co-x and Co-w (Geffroy 1997) to Pv01 (Gepts 1999). Both loci originated from the Jalo EEP558 parent in the BJ mapping population. Another resistance gene located in the vicinity of Co-1 is the Andean Ur-9 gene, which confers resistance to Uromyces appendiculatus, the causal agent of common bean rust (Kelly et al. 2003). While potentially very useful to transfer resistance from the Andean into the Mesoamerican gene pools, the two markers may be less useful for transfers within the Andean gene pool, as illustrated by the presence of the markers in the Andean mapping parents (Jalo EEP558 and California Dark Red Kidney) that do not carry the resistances.

A molecular marker for the Co-1 2 locus has previously been identified and mapped to LG Pv01 (Vallejo and Kelly 2008). However, no markers have been associated with the Co-1 4 allele. In the present study, co-segregation of the Co-14 and Phg-1 genes was observed in the AND 277 cultivar, revealing a complex cluster of resistance genes in the common bean. The linkage between the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers and the Co-14 and Phg-1 genes will be extremely important for marker-assisted selection in common bean breeding programs. This is the first report of the presence of genes for resistance to ANT and ALS in the same common bean variety and in the same chromosomal region. It is possible that all of these genes evolved from a common ancestral R-gene. In addition, the linkage between these two loci and the presence of the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers are valuable tools for breeding and will be particularly helpful to the pyramiding process. Moreover, the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 alleles have now been mapped to a cluster on LG Pv01, in which genes for resistance to ALS, ANT, common bacterial blight, Fusarium root rot, and white mold are now known to reside (Miklas and Singh 2007).

Pyramiding ANT, ALS and rust resistances is a main focus of many bean breeding programs throughout the world (Ragagnin et al. 2003; Miklas and Singh 2007). Co-1 4 is one of the main genes used in ANT resistance breeding programs due to its ample resistance spectrum. Similarly, Phg-1 is used for resistance to ALS. Because of their physical linkage and—cis configuration, Co-1 4 and Phg-1 tend to be inherited together yet can be indirectly monitored with the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers. The results presented here provide a first example of how genome synteny (as implemented in the PhaseolusGenes database). These markers will facilitate the pyramiding of these resistance genes into commercial cultivars, increase breeding efficiency, and reduce time and costs. The linkage between the CV542014 and TGA1.1 markers and the Co-1 4 and Phg-1 genes will be extremely important for marker-assisted introgression of the genes into elite cultivars to enhance the resistance in common bean breeding programs.

References

Afanador LK, Haley SD, Kelly JD (1993) Adoption of a ‘mini-prep’ DNA extraction protocol for RAPD marker analysis in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 36:10–11

Aggarwal VD, Pastor-Corrales MA, Chirwa RM, Buruchara RA (2004) Andean beans (Phaseolus vulgaris) with resistance to the angular leaf spot pathogen (Phaeoisariopsis griseola) in Southern and Eastern Africa. Euphytica 136:201–210

Alzate-Marin AL, Arruda KM, Barros EG, Moreira MA (2003) Allelism studies for anthracnose resistance genes of common bean cultivar AND 277. Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 46:173–174

Arruda KMA, Alzate-Marin AL, Oliveira MSG, Barros EG, Moreira MA (2008) Inheritance studies for anthracnose resistance genes of common bean cultivar AND 277. Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 51:170–171

Bean Core Map (2009) In: Bean improvement cooperative. http://www.css.msu.edu/bic/PDF/Bean_Core_map_2009.pdf

Blair MW, Pedraza F, Buendia HF, Gaitán-Solís E, Beebe SE, Gepts P, Tohme J (2003) Development of a genome-wide anchored microsatellite map for common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Theor Appl Genet 107:1362–1374

Caixeta ET, Borém A, Niestche S, Moreira MA, Barros EG (2003) Inheritance of angular leaf spot resistance in common bean line BAT 332 and identification of RAPD markers linked to the resistance gene. Euphytica 134:297–303

Caixeta ET, Borém A, Alzate-Marin AL, Fagundes S, Morais SMG, Barros EG, Moreira MA (2005) Allelic relationships for genes that confer resistance to angular leaf spot in common bean. Euphytica 145:237–245

Cardenas F, Adams MW, Andersen A (1964) The genetic system for reaction of field beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) to infection to three physiologic races of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Euphytica 13:178–186

Carvalho GA, Paula-Júnior TJ, Alzate-Marin AL, Nietsche S, Barros EG, Moreira MA (1998) Herança da resistência da linhagem AND-277 de feijoeiro-comum à raça 63–23 de Phaeoisariopsis griseola e identificação de marcador RAPD ligado ao gene de resistência. Fitopatologia Brasileira 23:482–485

Correa-Victoria FJ, Pastor-Corrales MA, Saettler AW (1989) Angular Leaf Spot. In: Schwartz HF, Pastor-Corrales MA (eds) Bean production problems in the tropics, 2nd edn. CIAT, Cali, Colombia, pp 59–76

Flor H (1971) Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu Rev Phytopathol 9:275–296

Freyre R, Skrock PW, Geffroy V, Adam-Blondon AF, Shirmohamadali A, Johnson WC, Llaca V, Nodari RO, Pereira PA, Tsai SM, Tohme J, Dron M, Nienhuis J, Vallejo CE, Gepts P (1998) Towards an integrated linkage map of common bean.4. Development of a core linkage map and alignment of RFLP maps. Theor Appl Genet 97:847–856

Gaitán-Solís E, Duque MC, Edwards KJ, Tohme J (2002) Microsatellite repeats in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris): isolation, characterization and cross-species amplification in Phaseolus ssp. Crop Sci 42:2128–2136

Geffroy V (1997) Dissection génétique de la résistance à Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, agent de l’anthracnose, chez deux génotypes représentatifs des pools géniques de Phaseolus vulgaris. Inst. Natl. Agron, Paris-Grignon

Geffroy V, Sicard D, Oliveira JCF, Sevignac M, Cohen S, Gepts P, Neema C, Langin T, Dron M (1999) Identification of an ancestral resistance gene cluster involved in the coevolution process between Phaseolus vulgaris ant its fungal pathogen Colletotrichum lindemuthianum. Mol Plant Microbe Interact 12:774–784

Geffroy V, Macadre C, David P, Pedrosa-Harand A, Sevignac M, Dauga C, Langin T (2009) Molecular analysis of a large subtelomeric nucleotide-binding-site-leucine-rich-repeat family in two representative genotypes of the major gene pools of Phaseolus vulgaris. Genetics 181:405–419

Gepts P (1999) Development of an integrated linkage map. In: Singh SP (ed). Common bean improvement in the twenty-first century. Developments in plant breeding, vol 7. Kluwer Acad. Pub. Dordrecht, The Netherlands, p 53–91

Gonçalves-Vidigal MC, Kelly JD (2006) Inheritance of anthracnose resistance in the common bean cultivar Widusa. Euphytica 151:411–419

Gonçalves-Vidigal MC, Sakiyama NS, Vidigal Filho PS, Amaral JRAT, Poletine JP, Oliveira VR (2001) Resistance of common bean cultivar AB 136 races 31 and 69 of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum: the Co-6 locus. Crop Breed Appl Biotechnol 1:99–104

Gonçalves-Vidigal MC, Vidigal Filho PS, Medeiros AF, Pastor-Corrales MA (2009) Common bean landrace Jalo Listras Pretas is the source of a new Andean anthracnose resistance gene. Crop Sci 49:133–138

Inglis DA, Hagedorn J, Rand RE (1988) Use of dry inoculum to evaluate beans for resistance to anthracnose and angular leaf spot. Plant Dis 72:771–774

Johnson WC, Gepts P (2002) The role of epistasis in controlling seed yield and other agronomic traits in an Andean × Mesoamerican cross of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Euphytica 125:69–79

Kelly JD, Vallejo VA (2004) A comprehensive review of the major genes conditioning resistance to anthracnose in common bean. Hort Sci 39:1196–1207

Kelly JD, Gepts P, Miklas PN, Coyne DP (2003) Tagging and mapping of genes and QTL and molecular marker-assisted selection for traits of economic importance in bean and cowpea. Field Crops Research 82:135–154

Liebenberg MM, Pretorius ZA (1997) A review of angular leaf spot of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Afr Plant Prot 3:81–106

Lincoln SE, Lander SL (1993) Mapmaker/exp 3.0 and Mapmaker/QTL 1.1. Whitehead Inst. of Med. Res. Tech Report, Cambridge, MA

Lopez CE, Acosta IF, Jara C, Pedraza P, Gaitan-Solis E, Gallego G, Beebe S, Thome J (2003) Identifying resistance gene analogs associated with resistances to different pathogens in common bean. Phytopathology 93:88–95

Mathur RS, Barnett HR, Lilly VG (1950) Sporulation of Colletotrichum lindemuthianum in culture. Phytopathology 40:104

McClean P, Mamidi S, McConnell M, Chikara S, Lee R (2010) Synteny mapping between common bean and soybean reveals extensive blocks of shared loci. BMC Genomics 11:184

McConnell M, Mamidi S, Lee R, Chikara S, Rossi M, Papa R, McClean P (2010) Synthetic relationships among legumes revealed using a gene-based genetic linkage map of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Theor Appl Genet Online First, 6 July

Melotto M, Kelly JD (2000) An allelic series at the Co-1 locus for anthracnose in common bean of Andean origin. Euphytica 116:143–149

Mendoza A, Hernandez F, Hernandez S, Ruíz M, de la Veja OM, Mora G, Acosta J, Simpson J (2001) Identification of Co-1 anthracnose resistance and linked molecular markers in common bean line A193. Plant Dis 85:252–255

Michelmore RW, Paran I, Kesseli RV (1991) Identification of markers linked to disease resistance genes by bulked segregant analysis: a rapid method to detect markers in specific genomic regions using segregating populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:9828–9832

Miklas PN, Singh SP (2007) Common bean. In: Kole C (ed) Genome mapping and molecular breeding in plants. Pulses, Sugar and Tuber Crops, vol 3. Springer, Berlin, p 1–31

Miklas PN, Pastor-Corrales MA, Jung G, Coyne DP, Kelly JD, McClean PE, Gepts P (2002) Comprehensive linkage map of bean rust resistance genes. Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 45:125–129

Miklas PN, Hu J, Grunwald NJ, Larsen KM (2006) Potential application of TRAP (targeted region amplified polymorphism) markers of mapping and tagging disease resistance traits in common bean. Crop Sci 46:910–916

Pastor-Corrales MA (1992) Recomendaciones y acuerdos del primer taller de antracnosis en América Latina. In: Pastor-Corrales MA (ed) La antracnosis del frijol común, Phaseolus vulgaris, en América Latina. CIAT, Cali, Colombia, pp 240–250

Pastor-Corrales MA (1996) Traditional and molecular confirmation of the coevolution of beans and pathogens in Latin America. Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 39:46–47

Pastor-Corrales MA, Castellanos G (1990) Biocontrol of bean rust with an avirulent isolate of Uromyces appendiculatus under field conditions. Phytopathology 80:515

Pastor-Corrales MA, Tu JC (1989) Anthracnose. In: Schwartz HF, Pastor-Corrales MA (eds) Bean production problems in the Tropics. CIAT, Cali, Colombia, pp 77–104

Pastor-Corrales MA, Otoya MM, Molina A, Singh SP (1995) Resistance to Colletotrichum lindemuthianum isolates from middle America and Andean South America in different common bean races. Plant Dis 79:63–67

Pedrosa-Harand A, Porch T, Gepts P (2008) Standard nomenclature for common bean chromosomes and linkage groups. Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 51:106–107

Ragagnin VA, Alzate-Marin AL, Souza TLPO, Arruda KM, Moreira MA, Barros EG (2003) Avaliação da resistência de isolinhas de feijoeiro a diferentes patótipos de Colletotrichum lindemuthianum, Uromyces appendiculatus e Phaeoisariopsis griseola. Fitopatologia Brasileira 28:591–596

Sanglard DA, Balbi BP, de Barros EG (2009) An efficient protocol for isolation, sporulation and maintenance of pseudocercospora griseola. Ann Rep Bean Improv Coop 52:62–63

Sartorato A (2004) Pathogenic variability and genetic diversity of Phaeoisariopsis griseola isolates from two counties in the state of Goias, Brazil. J Phytopathol 152:385–390

Vallejo V, Kelly JD (2002) The use of AFLP analysis to tag the Co-1 2 gene conditioning resistance to bean anthracnose. In: Proceedings of the X conference on plant and animal genome. http://www.intl-pag.org/pag/10/abstracts/PAGX_P233.html

Vallejo VA, Kelly JD (2008) Molecular tagging and characterization of alleles at the Co-1 anthracnose resistance locus in common. ICFAI Univ. J. Genetics Evol 1:7–20

Voorrips RE (2002) Mapchart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J Hered 93:77–78

Wortmann CS, Kirkby RA, Eledu CA, Allen DJ (1998) Atlas of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) production in Africa. CIAT, Cali, Colombia

Young RA, Kelly JD (1997) RAPD markers linked to three major anthracnose resistance genes in common bean. Crop Sci 37:940–946

Yu K, Park SJ, Poysa V, Gepts P (2000) Integration of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers into a molecular linkage map of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). J Hered 91:429–434

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank CNPq and Capes-Brazil, and Fundação Araucária for financial support. M.C. Gonçalves-Vidigal and P.S. Vidigal Filho were supported by grants from CNPq. A. S. Cruz and A. Garcia are recipients of a fellowship from CAPES. Funding for this research in the Gepts lab was provided by the Kirkhouse Trust.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by R. Varshney.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Gonçalves-Vidigal, M.C., Cruz, A.S., Garcia, A. et al. Linkage mapping of the Phg-1 and Co-1 4 genes for resistance to angular leaf spot and anthracnose in the common bean cultivar AND 277. Theor Appl Genet 122, 893–903 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-010-1496-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-010-1496-1