Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the inequality in medical care utilization and household catastrophic health spending (HCHS) between the poverty and non-poverty residents in rural Rwanda and their links with community-based health insurance (Mutuelles).

Methods

We used the 2005 and 2010 nationally representative Integrated Living Conditions Surveys. We estimated multilevel logistic regression models to obtain the adjusted levels and trends of both absolute and relative inequalities and examined associations between Mutuelles status and these inequalities.

Results

Significant inequality between the two income groups, in both absolute and relative measures of medical care utilization and HCHS remained unchanged in 2005 and 2010. Significant reduction in adjusted absolute inequality in percentage of HCHS between the two years was not associated with Mutuelles status.

Conclusions

While Mutuelles promoted medical care utilization and reduced HCHS, it did not play a significant role in reducing their inequalities by poverty status between 2005 and 2010. Future studies should assess the impact of additional strategies (e.g., the exemption of Mutuelles premiums and copayments for households living in poverty), on reducing inequality by poverty status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Achieving equal access to health care with financial risk protection is at the center of sustainable development agenda which stresses “leaving no one behind” (United Nations 2016). An important aspect of health equity lies in mitigating systematic inequalities in medical care utilization and financial risk protection between those living in poverty (poverty group) and those living above poverty (non-poverty group) (Braveman and Gruskin 2003a, b; Wagstaff and van Doorslaer 2000). Serious absolute or relative inequalities in medical care utilization and catastrophic health spending between the two income groups have been found in developing countries, such as Armenia, Burkina Faso, Rwanda, Indonesia, Vietnam, Chile, Turkey, China, India, Ghana, and Tanzania, with the poverty group usually less likely to use medical care and more likely to incur catastrophic health spending than the non-poverty group (Atun et al. 2013; Balarajan et al. 2011; Frenz et al. 2014; Hidayat et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2012; Mills et al. 2012; Parmar et al. 2014; Polonsky et al. 2009; Tang et al. 2008; Wagstaff et al. 2016). To achieve universal health coverage, other developing countries have adopted various social security or tax-based financing programs such as community-based health insurance (e.g., Armenia, Burkina Faso, Rwanda) (Lu et al. 2012; Parmar et al. 2014; Polonsky et al. 2009), social health insurance programs (e.g., China, Indonesia, Vietnam) (Hidayat et al. 2004; Tang et al. 2008; Wagstaff et al. 2016), national healthcare systems (e.g., Brazil, Cuba) (Atun et al. 2015), and a comprehensive healthcare reforms (e.g., Chile, Turkey) (Balarajan et al. 2011; Mills et al. 2012). While some of these programs or reforms were found to promote access to care or better financial risk protection for their enrollees than the uninsured (Balarajan et al. 2011; Hidayat et al. 2004; Lu et al. 2012; Mills et al. 2012; Parmar et al. 2014; Polonsky et al. 2009), little evidence shows that they were effective in mitigating the gaps in medical care utilization and financial risk protection between the poor and non-poor (Hidayat et al. 2004; Mills et al. 2012).

As a low-income agricultural country in central east Africa, Rwanda had a population of 11.3 million in 2014, with 83% of its population living in rural areas (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2015; World Bank 2017). Rwanda had a very weak public health system before 2000 and the majority of its population had no health insurance and had to pay for health services out-of-pocket (Schneider and Hanson 2006). Mutuelles, a community-based health insurance program, was piloted in three selected districts in 1999/2000 and started to be scaled up to the national level since 2006 (Lu et al. 2012). The Government of Rwanda (GoR) established Mutuelles to provide health insurance to rural residents and those in the informal economy so as to promote health equity and achieve universal health care.

Enrolling in Mutuelles is voluntary (Saksena et al. 2011). Between 2006 and 2010, each household paid a premium of 1000 Rwandan Franc (US$1.81) per member, 200 Rwandan Franc (US$0.36) copayments for each health center visit, and 10% of the hospital fee for hospitalization (Lu et al. 2012; Saksena et al. 2011). Since 2011, the poorest population (about 25%) was fully subsidized (exempted from paying premiums and copayments) by the government and donors (Binagwaho et al. 2014; Lu et al. 2016). About half of the funding of Mutuelles was contributed by annual member premiums, with the remaining half from various international and national agencies (Kalk et al. 2010; Lu et al. 2016; Saksena et al. 2011; World Health Organization 2009). The Mutuelles program collects and transfers risk-pooling funds to public health facilities on a regular basis to cover the expenses related to the provision of minimum service package to Mutuelles enrollees. Between 2005 and 2010, Mutuelles paid healthcare providers through a fee-for-service or performance-based payments (Kalk et al. 2010; Lu et al. 2016; Ministry of Health of Rwanda 2010; Saksena et al. 2011; World Health Organization 2009). Details on health care system in Rwanda are presented in Box A of the webappendix.

Previous studies have found that Mutuelles enrollment was associated with increases in medical care utilization among under-five children and pregnant women, improvements in child nutritional status, and decreases in household catastrophic health spending (HCHS) (Lu et al. 2012, 2016; Mejia-Guevara et al. 2015; Saksena et al. 2011; Schneider and Hanson 2006; Sekabaraga et al. 2011). A study, using data collected in 2000 at three rural districts in which Mutuelles was piloted, found that Mutuelles contributed to equity in using care across different wealth groups (Schneider and Hanson 2006). Little, however, is known about national-level inequality in medical care utilization and HCHS between the poverty and non-poverty residents and if Mutuelles was associated with inequality reduction over time.

Using the Rwandan nationally representative Integrated Living Conditions Survey (EICV) in 2005 and 2010, this study adds to the body of knowledge about health inequality and community-based health insurance in Rwanda in the following aspects: (1) we conducted the first empirical estimation of the level and trends of inequality, between non-poverty and poverty groups in rural Rwanda, in medical care utilization and HCHS; (2) we extended previous studies on Mutuelles by exploring its association with inequality in medical care utilization and HCHS; and 3) we performed sensitivity tests by varying inequality measures.

Methods

Data and sample

We used the repeated cross-sectional EICV surveys in 2005 and 2010 (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2011). The EICV measures household income and expenditure, demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, health insurance status, medical care utilization, and out-of-pocket health spending (OOPS). Details on its sampling and implementation process are presented in Box B of the webappendix.

Our study focused on rural residents which is the target of Mutuelles. To estimate the level and trends of inequality in medical care utilization, we used individual as the unit of analysis and included in the sample only those who reported being ill two weeks before the survey. The final sample size was 5305 in 2005 and 10,175 in 2010, respectively. To estimate the level and trends of inequality in HCHS, we used household as the unit of analysis and included all rural households in the two years, and the final sample size was 5198 in 2005 and 9759 in 2010.

To study the role of Mutuelles in reducing inequality in medical care utilization and HCHS, we further excluded those individuals (3.64 and 2.12% of the rural individuals in 2005 and 2010, respectively) or households (4.00 and 2.75% of rural households in 2005 and 2010, respectively) who enrolled in other health insurance plans, and kept only individuals or households enrolled in Mutuelles or uninsured. The final sample size for utilization analysis was 5112 and 9959 in 2005 and 2010, respectively. For analysis on HCHS, household OOPS included spending on inpatient and outpatient services, medical tests, drugs, transportation, and vaccination. The final sample size for household-level analysis was 4994 and 9529 in 2005 and 2010, respectively.

Variables

Analysis on medical care utilization among those reporting illness

We constructed a dichotomous outcome variable indicating any medical care (outpatient care, inpatient care, and medical tests) utilization among individuals reporting an illness in the previous two weeks of the survey. The EICV survey asked an individual whether or not he/she used any of these medical services without collecting the information about the intensity of service usage. Survey questions about items of medical care utilization in the EICV are presented in Supplementary Table A of the webappendix.

A dichotomous variable was constructed to indicate whether an individual participated in Mutuelles or was uninsured. A dichotomous poverty indicator recorded whether a household lived above or below the national poverty line. According to Rwandan government reports, 57 and 45% of households lived under the national poverty line in 2005 and 2010, respectively, and the definition of the national poverty line did not change between 2005 and 2010 (National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda 2013). Because there was no variable in the EICV indicating whether a household lived under the national poverty line, we constructed a poverty measure, similar to prior studies (Lu et al. 2016; Mejia-Guevara et al. 2015), that accounted for the shifting demographics in Rwanda. We defined poverty households as those in the first, second, and third wealth quintiles in 2005 (60% of total households in the survey) and the first and second wealth quintiles in 2010 (40% of total households in the survey), as they were close to the percentage of households living under the national poverty line (60 vs. 57% in 2005, and 40 vs. 45% in 2010).

We controlled for a number of demographic and socioeconomic variables including an individual’s age, gender, schooling of the household head, severity of illness, time to hospital, time to health center, and household size (Supplementary Box C).

Analysis on HCHS

We constructed a dichotomous outcome variable indicating whether or not a household had catastrophic health expenditure, defined as annual OOPS exceeding 40% of its annual capacity to pay (Xu et al. 2003, 2007). Details on obtaining HCHS are presented in Supplementary Box D.

In HCHS analyses, the Mutuelles indicator was constructed to indicate whether a household enrolled in Mutuelles or was uninsured. Other covariates included household head information (age, gender, and schooling), indicators on household having children under age five or disabled members, time to hospital, time to health center, and household size (Supplementary Box C).

Summary statistics of used variables are presented in Supplementary Tables B to E.

Statistical analysis

We conducted regression analyses to (1) obtain the adjusted levels and trends of inequalities in medical care utilization and HCHS between the poverty and non-poverty groups in 2005 and 2010, and (2) investigate the association between Mutuelles enrollment and inequality in medical care utilization and HCHS.

To measure adjusted inequality in medical care utilization and HCHS, we processed the analysis with pooled 2005 and 2010 data and used three-level logistic regression models with random intercepts by village and district, controlling for potential clustering effects at the village and district levels (Eq. 1).

where Logit(Utilizationijk/HCHSijk) represents the probability of using medical care or incurring HCHS for the ith individual or household in the jth village and kth district, Povertyijk is poverty status of ith individual or household in the jth village and kth district, 2010 is year indicator with reference year of 2005. β is a vector of coefficients for Xijk which is a vector of variables on individual or household characteristics including health insurance enrollment for the ith individual or household in the jth village and kth district, and ν0k and μ0jk represent between-district random-variation and between-village/within-district random variation, respectively.

With regression analyses, we were able to report (1) adjusted likelihood (and their 95% confidence intervals) of using medical care and incurring HCHS in 2005 and 2010 for poverty and non-poverty groups, respectively; and (2) adjusted inequality (and their 95% confidence intervals) in medical care utilization and HCHS between the two groups in each year. Absolute and relative measures have been commonly used in previous studies to measure the inequalities between two population groups on the basis of gender, race, or wealth quintiles (Barros et al. 2012; Frenz et al. 2014; World Health Organization 2017). Following these previous studies, we defined absolute inequality as the difference in likelihood of individuals using medical care or HCHS between the non-poverty and poverty groups. Relative inequality was measured with the ratio of the likelihood of medical care utilization or HCHS between the non-poverty and poverty groups. Results of estimation using Eq. (1) are presented in Supplementary Tables F and G.

To assessing the association between Mutuelles enrollment and inequality in medical care utilization or HCHS, we used the pooled data and adopted a model (Eq. 2) which enabled us to (1) identify the difference between Mutuelles enrollees and the uninsured in inequality of medical care utilization or HCHS by poverty status in 2005 and 2010, and (2) between Mutuelles status and changes in inequality over time by testing the significance of the coefficient of a three-way interaction term “Mutuelles*Poverty*2010.”

We used Stata 14.0 for all analyses.

Results

Adjusted levels and trends of inequalities in medical care utilization and HCHS

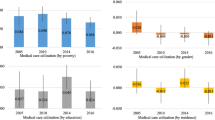

The adjusted absolute inequality in medical care utilization between the non-poverty and poverty groups was statistically significant from zero in 2005 (4.6%, 95% CI 1.9–7.4%) and 2010 (8.7%, 95% CI 6.8–10.6%), indicating that non-poverty group was more likely to use medical care than the poverty group. There was an increase in inequality of medical care utilization, but not statistically significant (Fig. 1). Inequality results on medical care utilization remained unchanged when using relative inequality measure (Supplementary Fig. A).

Adjusted trends of absolute inequalities between non-poverty and poverty groups in medical care utilization and household catastrophic health spending (Rural Rwanda 2005 and 2010). *Means that the reduction between 2005 and 2010 was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. 95% confidence interval is within the brackets

The adjusted absolute inequality in percentage of HCHS between non-poverty and poverty groups was significantly lower than zero in 2005 (− 7.0%, 95% CI − 8.5 to − 5.6%) and 2010 (− 3.3%, 95% CI − 4.4 to − 2.2%), indicating that non-poverty group was less likely to incur HCHS than the poverty group. The adjusted absolute inequality in HCHS by poverty status reduced significantly between 2005 and 2010 (Fig. 1). When using relative inequality measure, there was no significant difference in inequalities between 2005 and 2010 (Supplementary Fig. A).

Table 1 further investigates the trends of inequality by presenting medical care utilization and HCHS in 2005 and 2010 for poverty and non-poverty groups, respectively. For medical care utilization, only the non-poverty group had a significant increase in probability of using care (7.3%, 95% CI 2.5–12.0%). For HCHS, both the poverty and non-poverty groups had a significant reduction between the two years. The reduction in the non-poverty group (− 1.4% with 95% CI − 2.2 to − 0.5%) was significantly higher than that in the poverty group (− 5.2% in 2010 with 95% CI − 6.9 to − 3.4%) (Table 1).

Association between Mutuelles enrollment and inequality in medical care utilization

There was a significant increase in percentage of individuals enrolled in Mutuelles, from 42.4% (95% CI 41.7–43.0%) in 2005 to 67.5% (95% CI 67.1–67.9%) in 2010. The same trends were observed in both poverty (from 37.7% in 2005 to 57.7% in 2010) and non-poverty groups (from 51.7% in 2005 to 75.1% in 2010) (Table 2).

In 2005 and 2010, there were no significant differences in absolute inequality (by poverty status) in medical care utilization between the Mutuelles enrollees and uninsured individuals (e.g., 6.3% [95% CI 3.8–8.8%] for Mutuelles enrollees and 10.0% [95% CI 6.9–13.1%] for uninsured in 2010). Between 2005 and 2010, the inequality by poverty status was exacerbated for both Mutuelles enrollees and uninsured individuals, though these changes were insignificant (Fig. 2). The results were similar for the relative inequality measure, with one exception: in 2010, the relative inequality of medical care utilization was smaller among Mutuelles enrollees than the uninsured (Supplementary Fig. B). The odds ratio of three-way interaction term “Mutuelles*Poverty*2010” is 1.24 and not statistically significant (Supplementary Table H).

Adjusted trends of absolute inequalities between non-poverty and poverty groups by Mutuelles status in medical care utilization and household catastrophic health spending (Rural Rwanda 2005 and 2010). *Means that the reduction between 2005 and 2010 was statistically significant at the 0.05 level. 95% confidence interval is within the brackets. Mutuelles is a community-based health insurance program targeted at rural residents in Rwanda

These results suggest that, compared to the uninsured, Mutuelles status was not associated with a significant reduction in inequality in medical care utilization between 2005 and 2010.

Association between Mutuelles enrollment and inequality in HCHS

In each year, there was less adjusted absolute inequality in HCHS among Mutuelles households compared to uninsured households, but these differences were not statistically significant. Between 2005 and 2010, for the Mutuelles enrollees, absolute inequality in HCHS was reduced, but not significantly. For uninsured households, absolute inequality in HCHS was significantly reduced (Fig. 2).

When using the relative inequality measure, there was no significant change in relative inequality between 2005 and 2010 for either Mutuelles or uninsured households (Supplementary Fig. B). The odds ratio of the three-way interaction term “Mutuelles*Poverty*2010” in HCHS analysis was not statistically significant at the 0.05 level (Supplementary Table I).

These results suggest that Mutuelles status was not associated with a significant change in absolute or relative inequality in HCHS, when compared to the uninsured.

Discussion

The study has two salient findings. First, significant inequality between the poverty and non-poverty groups persisted when using both absolute and relative inequality measures: non-poor residents were more likely to use medical care and less likely to incur HCHS than poor residents. Second, between 2005 and 2010, the inequality (both absolute and relative) in medical care utilization increased with no statistical significance and the inequality (absolute only) in HCHS significantly reduced. Mutuelles status was not associated with the change in inequality in both medical care utilization and HCHS.

Plausible explanations on Mutuelles’s insignificant role in mitigating the inequality by poverty status in medical care utilization could be the following. First, the annual premium (US$ 1.81) of the Mutuelles and its copayments (US$ 0.36 per visit and 10% of hospitalization fee in 2010) may have prevented poverty enrollees (Community-based health insurance in Rwanda website 2017), who lived with $0.32 per person per day, from participating in the program or from seeking needed care even with the enrollment. Second, services may not be available for the rural residents. Though Mutuelles enrollees were entitled by law to a minimum service package at the health center and a complementary service package at the district hospital, it was estimated that, on average, only 40% of child and maternal services were provided in rural health centers in 2010 (Lu et al. 2017). Households living in poverty had less financial capacity to seek care in the provincial or national hospitals than the households in the non-poverty group. In our study, even for the non-poverty group with Mutuelles, the average likelihood of using needed care among the Mutuelles enrollees in the non-poverty group was only 53.4% in 2010, the highest rate among all groups.

The reduction in inequality in HCHS between 2005 and 2010 could be mainly driven by the reduction in medical care use in the uninsured households: there was a higher rate of reduction in medical care utilization in the poverty group (26%, from 19.2% in 2005 to 14.3% in 2010%, Supplementary Table J) than that in the non-poverty group (5%, from 25.6% in 2005 to 24.3% in 2010%, Supplementary Table J) between the two years. Less medical care utilization led to less out-of-pocket health spending, which, in turn, led to lower rate of HCHS. This is concerning, as those who had need for medical case should have access to it.

Our study has the following limitations. First, with repeated cross-sectional data, we were not able to identify if the causal link exists between Mutuelles enrollment and medical care utilization or HCHS. Second, when constructing poverty indicator, 3% of non-poverty households were misallocated to the poverty group in 2005 and 5% of poverty households were misallocated to the non-poverty group in 2010. This misallocation could lead to under-estimation of inequality in medical care utilization between the two income groups in both 2005 and 2010 due to possible increase in utilization rate among the poverty group in 2005 by including non-poverty households and decrease in utilization rate among the non-poverty group in 2010 by including poverty households. Estimation on trends might be less affected by the misallocation as the inequality was underestimated in both years. Third, while this is the first study to measure inequality between the poverty and non-poverty groups and assess its link with Mutuelles, many important questions remain unanswered. For example, with limited resources in Rwanda, how to best design pro-equity insurance program? Except for Mutuelles, were there other risk factors (such as education, health need, and geographical difficulties) that contribute to the inequalities between the two income groups? Evidence on these questions should be weighed in policy-making process. Fourth, in this study, due to unavailable data, we were not able to perform analysis on inequalities in the services that were not included in the minimum service package of the Mutuelles. Fifth, availability of health services might also be an important predictor of inequalities in medical care utilization and HCHS but was not available in the EICV dataset. We, therefore, were unable to control for availability of health services in the analysis.

Like many other developing countries, one of the major challenges faced by the GoR is how to ensure equal access to medical care and financial risk protection for the poverty households. This study suggested that Mutuelles program did not play significant role in reducing inequalities by poverty status between 2005 and 2010. Since 2011, the GoR has started providing a full subsidy for premiums and copayments for the poorest population in Rwanda (about 25%) (Sayinzoga and Bijlmakers 2016). Future study should use more recent data as it becomes available to examine the effects of the subsidy on inequality of medical care utilization and HCHS. In other developing countries, policy interventions, such as conditional cash transfers or Medical Financial Assistance (Gertler 2004; Lagarde et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2017), have been implemented to assist the indigent households in overcoming financial difficulties to access medical care. Community health workers program has also been found to be an effective in reaching out the most vulnerable households by addressing geographical, financial and sociocultural barriers (McPake et al. 2015; Singh and Sachs 2013). These programs could be considered as the instruments to address the ability to pay for medical care of those living in poverty. In the long term, eliminating poverty is a key solution to health care inequality and requires strong commitment from the governments.

References

Atun R, Aydın S, Chakraborty S et al (2013) Universal health coverage in Turkey: enhancement of equity. Lancet 382:65–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61051-X

Atun R, de Andrade LO, Almeida G et al (2015) Health-system reform and universal health coverage in Latin America. Lancet 385:1230–1247. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61646-9

Balarajan Y, Selvaraj S, Subramanian SV (2011) Health care and equity in India. Lancet 377:505–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61894-6

Barros AJ, Ronsmans C, Axelson H et al (2012) Equity in maternal, newborn, and child health interventions in Countdown to 2015: a retrospective review of survey data from 54 countries. Lancet 379:1225–1233. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60113-5

Binagwaho A, Farmer PE, Nsanzimana S et al (2014) Rwanda 20 years on: investing in life. Lancet 384:371–375. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60574-2

Braveman P, Gruskin S (2003a) Defining equity in health. J Epidemiol Commun H 57:254–258

Braveman P, Gruskin S (2003b) Poverty, equity, human rights and health B World Health. Organ 81:539–545

Community based health insurance in Rwanda website (2017). http://www.cbhirwanda.org.rw. Accessed 16 Nov 2016

Frenz P, Delgado I, Kaufman JS, Harper S (2014) Achieving effective universal health coverage with equity: evidence from Chile. Health Policy Plan 29:717–731. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czt054

Gertler P (2004) Do conditional cash transfers improve child health? Evidence from PROGRESA’s control randomized experiment. Am Econ Rev 94:336–341. https://doi.org/10.1257/0002828041302109

Hidayat B, Thabrany H, Dong H, Sauerborn R (2004) The effects of mandatory health insurance on equity in access to outpatient care in Indonesia. Health Policy Plan 19:322–335

Kalk A, Groos N, Karasi JC, Girrbach E (2010) Health systems strengthening through insurance subsidies: the GFATM experience in Rwanda. Trop Med Int Health 15:94–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2009.02424.x

Lagarde M, Haines A, Palmer N (2007) Conditional cash transfers for improving uptake of health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. JAMA 298:1900–1910. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.298.16.1900

Liu K, Yang J, Lu C (2017) Is the medical financial assistance program an effective supplement to social health insurance for low-income households in China? A cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health 16:138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0638-3

Lu C, Chin B, Lewandowski JL et al (2012) Towards universal health coverage: an evaluation of rwanda Mutuelles in its first eight years. Plos One 7:e39282

Lu C, Mejia-Guevara I, Hill K, Farmer P, Subramanian SV, Binagwaho A (2016) Community-based health financing and child stunting in rural Rwanda. Am J Public Health 106:49–55. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302913

Lu C, Cook B, Desmond C (2017) Does foreign aid crowd out government investments? Evidence from rural health centres in Rwanda. BMJ Global Health 2:e000364. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000364

McPake B, Edoka I, Witter S et al (2015) Cost-effectiveness of community-based practitioner programmes in Ethiopia, Indonesia and Kenya. Bull World Health Organ 93:631A–639A. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.144899

Mejia-Guevara I, Hill K, Subramanian SV, Lu CL (2015) Service availability and association between Mutuelles and medical care usage for under-five children in rural Rwanda: a statistical analysis with repeated cross-sectional data. BMJ Open 5:e008814. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008814

Mills A, Ataguba JE, Akazili J et al (2012) Equity in financing and use of health care in Ghana, South Africa, and Tanzania: implications for paths to universal coverage. Lancet 380:126–133

Ministry of Health of Rwanda (2010) Rwanda national health insurance policy. Ministry of Health of Rwanda, Kigali

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (2011) Integrated living conditions survey (2000, 2005, and 2010). http://www.statistics.gov.rw/survey/integrated-household-living-conditions-survey-eicv. Accessed 16 Nov 2016

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (2013) Rwanda statistical year book 2012. National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda, Kigali

National Institute of Statistics of Rwanda (2015) The fourth integrated household living conditions survey (EICV 4). National Institute of Statistics. http://www.statistics.gov.rw/publication/rwanda-poverty-profile-report-results-eicv-4. Accessed 16 Nov 2016

Parmar D, De Allegri M, Savadogo G, Sauerborn R (2014) Do community-based health insurance schemes fulfil the promise of equity? A study from Burkina Faso. Health Policy Plan 29:76–84

Polonsky J, Balabanova D, McPake B, Poletti T, Vyas S, Ghazaryan O, Yanni MK (2009) Equity in community health insurance schemes: evidence and lessons from Armenia. Health Policy Plan 24:209–216. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czp001

Saksena P, Antunes AF, Xu K, Musango L, Carrin G (2011) Mutual health insurance in Rwanda: evidence on access to care and financial risk protection. Health Policy 99:203–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.09.009

Sayinzoga F, Bijlmakers L (2016) Drivers of improved health sector performance in Rwanda: a qualitative view from within. BMC Health Serv Res 16:123. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1351-4

Schneider P, Hanson K (2006) Horizontal equity in utilisation of care and fairness of health financing: a comparison of micro-health insurance and user fees in Rwanda. Health Econ 15:19–31. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.1014

Sekabaraga C, Diop F, Soucat A (2011) Can innovative health financing policies increase access to MDG-related services? Evidence from Rwanda. Health Policy Plann 26:Ii52–Ii62

Singh P, Sachs JD (2013) 1 million community health workers in sub-Saharan Africa by 2015. Lancet 382:363–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62002-9

Tang S, Meng Q, Chen L, Bekedam H, Evans T, Whitehead M (2008) Tackling the challenges to health equity in China. Lancet 372:1493–1501. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61364-1

United Nations (2016) The sustainable development goals report 2016. United Nations. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2016/leaving-no-one-behind. Accessed 15 May 2017

Wagstaff A, van Doorslaer E (2000) Measuring and testing for inequity in the delivery of health care. J Hum Resour 35:716–733

Wagstaff A, Nguyen HT, Dao H, Bales S (2016) Encouraging health insurance for the informal sector: a cluster randomized experiment in Vietnam. Health Econ 25:663–674. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3293

World Bank (2017) World development indicators. Rwanda: Population, total. World Bank. http://data.worldbank.org/country/rwanda?view=chart. Accessed 16 Nov 2016

World Health Organization (2009) Health financing systems review of Rwanda: options for universal coverage. World Health Organization, Geneva

World Health Organization (2017) Health Equity Assessment Toolkit (HEAT): software for exploring and comparing health inequalities in countries. Built-in database edition. Version 1.1. World Health Organization, Geneva

Xu K, Evans DB, Kawabata K, Zeramdini R, Klavus J, Murray CJ (2003) Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet 362:111–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5

Xu K, Evans DB, Carrin G, Aguilar-Rivera AM, Musgrove P, Evans T (2007) Protecting households from catastrophic health spending. Health Aff (Millwood) 26:972–983. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.26.4.972

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

This article is part of the special issue “Environmental and health equity”.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, K., Cook, B. & Lu, C. Health inequality and community-based health insurance: a case study of rural Rwanda with repeated cross-sectional data. Int J Public Health 64, 7–14 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1115-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1115-5