Abstract

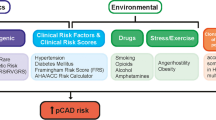

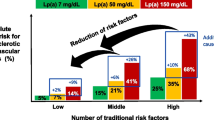

Cardiovascular disease is the foremost cause of morbidity and mortality in the Western world. Atherosclerosis followed by thrombosis (atherothrombosis) is the pathological process underlying most myocardial, cerebral, and peripheral vascular events. Atherothrombosis is a complex and heterogeneous inflammatory process that involves interactions between many cell types (including vascular smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, and platelets) and processes (including migration, proliferation, and activation). Despite a wealth of knowledge from many recent studies using knockout mouse and human genetic studies (GWAS and candidate approach) identifying genes and proteins directly involved in these processes, traditional cardiovascular risk factors (hyperlipidemia, hypertension, smoking, diabetes mellitus, sex, and age) remain the most useful predictor of disease. Eicosanoids (20 carbon polyunsaturated fatty acid derivatives of arachidonic acid and other essential fatty acids) are emerging as important regulators of cardiovascular disease processes. Drugs indirectly modulating these signals, including COX-1/COX-2 inhibitors, have proven to play major roles in the atherothrombotic process. However, the complexity of their roles and regulation by opposing eicosanoid signaling, have contributed to the lack of therapies directed at the eicosanoid receptors themselves. This is likely to change, as our understanding of the structure, signaling, and function of the eicosanoid receptors improves. Indeed, a major advance is emerging from the characterization of dysfunctional naturally occurring mutations of the eicosanoid receptors. In light of the proven and continuing importance of risk factors, we have elected to focus on the relationship between eicosanoids and cardiovascular risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Roger VL et al (2012) Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 125(1):e2–e220

Ross R (1999) Atherosclerosis–an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med 340(2):115–126

Weber C, Noels H (2011) Atherosclerosis: current pathogenesis and therapeutic options. Nat Med 17(11):1410–1422

Jackson SP (2011) Arterial thrombosis—insidious, unpredictable and deadly. Nat Med 17(11):1423–1436

Bird DA et al (1999) Receptors for oxidized low-density lipoprotein on elicited mouse peritoneal macrophages can recognize both the modified lipid moieties and the modified protein moieties: implications with respect to macrophage recognition of apoptotic cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci 96(11):6347–6352

Glass CK, Witztum JL (2001) Atherosclerosis: the road ahead. Cell 104(4):503–516

Libby P et al (2010) Inflammation in atherosclerosis: transition from theory to practice. Circ J 74(2):213–220

Rocha VZ, Libby P (2009) Obesity, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 6(6):399–409

Libby P (2002) Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Nature 420(6917):868–874

Angiolillo DJ, Ueno M, Goto S (2010) Basic principles of platelet biology and clinical implications. Circ J 74(4):597–607

Kaufmann BA et al (2010) Molecular imaging of the initial inflammatory response in atherosclerosis: implications for early detection of disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30(1):54–59

Braun OO et al (2008) Primary and secondary capture of platelets onto inflamed femoral artery endothelium is dependent on P-selectin and PSGL-1. Eur J Pharmacol 592(1–3):128–132

Furie B, Furie BC (2004) Role of platelet P-selectin and microparticle PSGL-1 in thrombus formation. Trends Mol Med 10(4):171–178

Theilmeier G et al (2002) Endothelial von Willebrand factor recruits platelets to atherosclerosis-prone sites in response to hypercholesterolemia. Blood 99(12):4486–4493

Ruggeri ZM (2002) Platelets in atherothrombosis. Nat Med 8(11):1227–1234

Gawaz M, Langer H, May AE (2005) Platelets in inflammation and atherogenesis. J Clin Invest 115(12):3378–3384

Jackson SP (2007) The growing complexity of platelet aggregation. Blood 109(12):5087–5095

Denis CV, Wagner DD (2007) Platelet adhesion receptors and their ligands in mouse models of thrombosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(4):728–739

Varga-Szabo D, Pleines I, Nieswandt B (2008) Cell adhesion mechanisms in platelets. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28(3):403–412

Jennings LK (2009) Mechanisms of platelet activation: need for new strategies to protect against platelet-mediated atherothrombosis. Thromb Haemost 102(2):248–257

Kapoor JR (2008) Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med 358(15):1638 (author reply 1638–1639)

Davi G, Patrono C (2007) Platelet activation and atherothrombosis. N Engl J Med 357(24):2482–2494

Yousuf O, Bhatt DL (2011) The evolution of antiplatelet therapy in cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 8(10):547–559

Hirsh J (1987) Hyperactive platelets and complications of coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 316(24):1543–1544

Panigrahy D et al (2010) Cytochrome P450-derived eicosanoids: the neglected pathway in cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 29(4):723–735

Nithipatikom K, Gross GJ (2010) Review article: epoxyeicosatrienoic acids: novel mediators of cardioprotection. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther 15(2):112–119

Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA (2011) Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 31(5):986–1000

Sala A, Folco G, Murphy RC (2010) Transcellular biosynthesis of eicosanoids. Pharmacol Rep 62(3):503–510

Rokach J et al (2004) Total synthesis of isoprostanes: discovery and quantitation in biological systems. Chem Phys Lipids 128(1–2):35–56

Janssen LJ (2001) Isoprostanes: an overview and putative roles in pulmonary pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280(6):L1067–L1082

Coleman RA, Smith WL, Narumiya S (1994) International union of pharmacology classification of prostanoid receptors: properties, distribution, and structure of the receptors and their subtypes. Pharmacol Rev 46(2):205–229

Drazen JM et al (1980) Comparative airway and vascular activities of leukotrienes C-1 and D in vivo and in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77(7):4354–4358

Hasegawa S et al (2010) Functional expression of cysteinyl leukotriene receptors on human platelets. Platelets 21(4):253–259

Nonaka Y, Hiramoto T, Fujita N (2005) Identification of endogenous surrogate ligands for human P2Y12 receptors by in silico and in vitro methods. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337(1):281–288

Node K et al (1999) Anti-inflammatory properties of cytochrome P450 epoxygenase-derived eicosanoids. Science 285(5431):1276–1279

Li N et al (2011) Use of metabolomic profiling in the study of arachidonic acid metabolism in cardiovascular disease. Congest Heart Fail 17(1):42–46

Bellien J et al (2011) Modulation of cytochrome-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids pathway: a promising pharmacological approach to prevent endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases? Pharmacol Ther 131(1):1–17

Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Harris RC (2000) Cytochrome P450 and arachidonic acid bioactivation: molecular and functional properties of the arachidonate monooxygenase. J Lipid Res 41(2):163–181

Fleming I et al (2001) Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor synthase (cytochrome P450 2C9) is a functionally significant source of reactive oxygen species in coronary arteries. Circ Res 88(1):44–51

Viswanathan S et al (2003) Involvement of CYP 2C9 in mediating the proinflammatory effects of linoleic acid in vascular endothelial cells. J Am Coll Nutr 22(6):502–510

CDC (2011) Prevalence of coronary heart disease—United States, 2006–2010. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60(40):1377–1381

Splansky GL et al (2007) The Third Generation Cohort of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Framingham Heart Study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol 165(11):1328–1335

Stewart ST, Cutler DM, Rosen AB (2009) Forecasting the effects of obesity and smoking on U.S. life expectancy. N Engl J Med 361(23):2252–2260

ADVANCE (2008) Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358(24):2560–2572

ACCORD Group (2008) Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358(24):2545–2559

Duckworth W et al (2009) Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 360(2):129–139

Cushman WC et al (2010) Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 362(17):1575–1585

Zoungas S et al (2010) Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med 363(15):1410–1418

Fisher M, Loscalzo J (2011) The perils of combination antithrombotic therapy and potential resolutions. Circulation 123(3):232–235

Angiolillo DJ et al (2011) Differential effects of omeprazole and pantoprazole on the pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of clopidogrel in healthy subjects: randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover comparison studies. Clin Pharmacol Ther 89(1):65–74

Wilson PW et al (1998) Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 97(18):1837–1847

Wilson PWF, Castelli WP, Kannel WB (1987) Coronary risk prediction in adults (The Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 59(14):G91–G94

Yanes LL, Reckelhoff JF (2011) Postmenopausal hypertension. Am J Hypertens 24(7):740–749

Schenck-Gustafsson K et al (2011) EMAS position statement: managing the menopause in the context of coronary heart disease. Maturitas 68(1):94–97

Egan K et al (2004) COX-2-derived prostacyclin confers atheroprotection on female mice. Science 306(5703):1954–1957

Turner EC, Kinsella BT (2010) Estrogen increases expression of the human prostacyclin receptor within the vasculature through an ERalpha-dependent mechanism. J Mol Biol 396(3):473–486

Ridker PM et al (2005) A randomized trial of low-dose aspirin in the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med 352(13):1293–1304

Smith DD et al (2010) Increased aortic atherosclerotic plaque development in female apolipoprotein E-null mice is associated with elevated thromboxane A2 and decreased prostacyclin production. J Physiol Pharmacol 61(3):309–316

Leslie CA, Gonnerman WA, Cathcart ES (1987) Gender differences in eicosanoid production from macrophages of arthritis-susceptible mice. J Immunol 138(2):413–416

Zhou Y et al (2005) Gender differences of renal CYP-derived eicosanoid synthesis in rats fed a high-fat diet[ast]. Am J Hypertens 18(4):530–537

Ward NC et al (2005) Urinary 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid excretion is associated with oxidative stress in hypertensive subjects. Free Radical Biol Med 38(8):1032–1036

Ward NC et al (2004) Urinary 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is associated with endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation 110(4):438–443

Yanes LL et al (2011) Postmenopausal hypertension: role of 20-HETE. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300(6):R1543–R1548

Liang C-J et al (2011) 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid inhibits ATP-induced COX-2 expression via peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-α in vascular smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 163(4):815–825

Tunctan B et al (2011) Contribution of vasoactive eicosanoids and nitric oxide production to the effect of selective cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, NS-398, on endotoxin-induced hypotension in rats. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford, pp 877–882

Tsai IJ et al (2011) 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid synthesis is increased in human neutrophils and platelets by angiotensin II and endothelin-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300(4):H1194–H1200

Lange A et al (1997) 20-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid-induced vasoconstriction and inhibition of potassium current in cerebral vascular smooth muscle is dependent on activation of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem 272(43):27345–27352

Gebremedhin D et al (1998) Cat cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells express cytochrome P450 4A2 enzyme and produce the vasoconstrictor 20-HETE which enhances L-type Ca2+ current. J Physiol 507(3):771–781

Kiowski W et al (1991) Endothelin-1-induced vasoconstriction in humans. Reversal by calcium channel blockade but not by nitrovasodilators or endothelium-derived relaxing factor. Circulation 83(2):469–475

Nelson MT et al (1990) Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 259(1):C3–C18

Egan BM, Zhao Y, Axon RN (2010) US trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension, 1988–2008. J Am Med Assoc 303(20):2043–2050

Bibbins-Domingo K et al (2010) Projected effect of dietary salt reductions on future cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 362(7):590–599

Collaboration APCS (2006) The impact of cardiovascular risk factors on the age-related excess risk of coronary heart disease. Int J Epidemiol 35(4):1025–1033

Graessler J et al (2009) Top-down lipidomics reveals ether lipid deficiency in blood plasma of hypertensive patients. PLoS One 4(7):e6261

Quehenberger O, Dennis EA (2011) The human plasma lipidome. N Engl J Med 365(19):1812–1823

Gryglewski RJ (2008) Prostacyclin among prostanoids. Pharmacol Rep 60(1):3–11

Torpy JM, Lynm C, Glass RM (2010) Hypertension. J Am Med Assoc 303(20):2098

Blaustein MP et al (2011) How NaCl raises blood pressure: a new paradigm for the pathogenesis of salt-dependent hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 302:H1031–H1049

Beckett NS et al (2008) Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 358(18):1887–1898

Cooper-DeHoff RM et al (2010) Tight blood pressure control and cardiovascular outcomes among hypertensive patients with diabetes and coronary artery disease. J Am Med Assoc 304(1):61–68

Fisher JP, Paton JFR (2011) The sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: implications for hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. doi:10.1038/jhh.2011.66

Orlov SN, Tremblay J, Hamet P (1996) cAMP signaling inhibits dihydropyridine-sensitive Ca2+ influx in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 27(3):774–780

Kawabe J, Ushikubi F, Hasebe N (2010) Prostacyclin in vascular diseases. Recent insights and future perspectives. Circ J 74(5):836–843

Stitham J et al (2011) Prostacyclin: an inflammatory paradox. Front Pharmacol 2:24

Cheng Y et al (2002) Role of prostacyclin in the cardiovascular response to thromboxane A2. Science 296(5567):539–541

Yu Y et al (2009) Cyclooxygenase-2-dependent prostacyclin formation and blood pressure homeostasis. Circ Res 106(2):337–345

Arehart E et al (2008) Acceleration of cardiovascular disease by a dysfunctional prostacyclin receptor mutation: potential implications for cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition. Circ Res 102(8):986–993

Jia Z et al (2006) Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 increases sensitivity to salt loading and angiotensin II infusion. Circ Res 99(11):1243–1251

Jia Z, Wang H, Yang T (2009) Mice lacking mPGES-1 are resistant to lithium-induced polyuria. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 297(6):F1689–F1696

Woodward DF, Jones RL, Narumiya S (2011) International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXXIII: classification of prostanoid receptors, updating 15 years of progress. Pharmacol Rev 63(3):471–538

Suzuki J-I et al (2011) Roles of prostaglandin E2 in cardiovascular diseases focus on the potential use of a novel selective EP4 receptor agonist. Int Heart J 52(5):266–269

Stock JL et al (2001) The prostaglandin E2 EP1 receptor mediates pain perception and regulates blood pressure. J Clin Invest 107(3):325–331

Guan Y et al (2007) Antihypertensive effects of selective prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype 1 targeting. J Clin Investig 117(9):2496–2505

Ai D et al (2007) Angiotensin II up-regulates soluble epoxide hydrolase in vascular endothelium in vitro and in vivo. Proc Nat Acad Sci 104(21):9018–9023

Campbell WB et al (1996) Identification of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res 78(3):415–423

Bellien J, Thuillez C, Joannides R (2008) Contribution of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors to the regulation of vascular tone in humans. Fundam Clin Pharmacol 22(4):363–377

Zhao X et al (2003) Salt-sensitive hypertension after exposure to angiotensin is associated with inability to upregulate renal epoxygenases. Hypertension 42(4):775–780

Fitzpatrick FA et al (1986) Inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity and platelet aggregation by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Influence of stereochemistry. J Biol Chem 261(32):15334–15338

Krötz F et al (2004) Membrane potential-dependent inhibition of platelet adhesion to endothelial cells by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Arteri Thromb Vasc Biol 24(3):595–600

Krotz F et al (2004) Membrane-potential-dependent inhibition of platelet adhesion to endothelial cells by epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24(3):595–600

Maier KG, Roman RJ (2001) Cytochrome P450 metabolites of arachidonic acid in the control of renal function. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 10(1):81–87

Athirakul K et al (2008) Increased blood pressure in mice lacking cytochrome P450 2J5. FASEB J 22(12):4096–4108

Campbell WB et al (2002) 14,15-Dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acid relaxes bovine coronary arteries by activation of KCa channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282(5):H1656–H1664

Imig JD et al (2002) Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition lowers arterial blood pressure in angiotensin II hypertension. Hypertension 39(2):690–694

Liu Y et al (2005) The antiinflammatory effect of laminar flow: the role of PPARγ, epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, and soluble epoxide hydrolase. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 102(46):16747–16752

Behm DJ et al (2009) Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids function as selective, endogenous antagonists of native thromboxane receptors: identification of a novel mechanism of vasodilation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 328(1):231–239

Yamagishi K et al (2008) Fish, ω-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and mortality from cardiovascular diseases in a nationwide community-based cohort of Japanese men and women: the JACC (Japan Collaborative Cohort Study for Evaluation of Cancer Risk) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 52(12):988–996

De Caterina R (2011) n-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med 364(25):2439–2450

Nakayama M et al (1999) Low dose of eicosapentaenoic acid inhibits the exaggerated growth of vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats through suppression of transforming growth factor-beta. J Hypertens 17(10):1421–1430

Serebruany VL et al (2011) Early impact of prescription omega-3 fatty acids on platelet biomarkers in patients with coronary artery disease and hypertriglyceridemia. Cardiology 118(3):187–194

Phang M et al (2012) Acute supplementation with eicosapentaenoic acid reduces platelet microparticle activity in healthy subjects. J Nutr Biochem. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2011.06.006

Larsen BT et al (2008) Hydrogen peroxide inhibits cytochrome p450 epoxygenases: interaction between two endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors. Circ Res 102(1):59–67

Bauersachs J et al (1996) Nitric oxide attenuates the release of endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor. Circulation 94(12):3341–3347

Zalba G et al (2001) Oxidative stress in arterial hypertension: role of NAD(P)H oxidase. Hypertension 38(6):1395–1399

Alexander RW (1995) Theodore Cooper Memorial Lecture. Hypertension and the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Oxidative stress and the mediation of arterial inflammatory response: a new perspective. Hypertension 25(2):155–161

Weintraub WS et al (1985) Importance of total life consumption of cigarettes as a risk factor for coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 55(6):669–672

Bazzano LA et al (2003) Relationship between cigarette smoking and novel risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the United States. Ann Intern Med 138(11):891–897

Sokolowska B et al (2010) Influence of leukotriene biosynthesis inhibition on heart rate in patients with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 145(3):625–626

Kawabata K et al (2010) Inhibition of secretory phospholipase A2 activity attenuates acute cardiogenic pulmonary edema induced by isoproterenol infusion in mice after myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 56(4):369–378. doi:10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181ef1aab

Mozaffarian D, Wu JHY (2011) Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: effects on risk factors, molecular pathways, and clinical events. J Am Coll Cardiol 58(20):2047–2067

Sanak M et al (2010) Pharmacological inhibition of leukotriene biosynthesis: effects on the heart conductance. J Physiol Pharmacol 61(1):53–58

Mozes T et al (1991) Sequential release of eicosanoids during endotoxin-induced shock in anesthetized pigs. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 42(4):209–216

Gesquiere L, Loreau N, Blache D (2000) Role of the cyclic AMP-dependent pathway in free radical-induced cholesterol accumulation in vascular smooth muscle cells. Free Radical Biol Med 29(2):181–190

Makheja AN (1992) Atherosclerosis: the eicosanoid connection. Mol Cell Biochem 111(1):137–142

O’Brien JJ et al (2007) The platelet as a therapeutic target for treating vascular diseases and the role of eicosanoid and synthetic PPARγ ligands. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 82(1–4):68–76

Xie YH et al (2010) Up-regulation of G-protein-coupled receptors for endothelin and thromboxane by lipid-soluble smoke particles in renal artery of rat. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 107(4):803–812

Milara J et al (2010) Cigarette smoke exposure up-regulates endothelin receptor B in human pulmonary artery endothelial cells: molecular and functional consequences. Br J Pharmacol 161(7):1599–1615

Vayssettes-Courchay C et al (2010) Role of thromboxane TP and angiotensin AT1 receptors in lipopolysaccharide-induced arterial dysfunction in the rabbit: an in vivo study. Eur J Pharmacol 634(1–3):113–120

Agarwal R (2005) Smoking, oxidative stress and inflammation: impact on resting energy expenditure in diabetic nephropathy. BMC Nephrol 6:13

Taylor A, Bruno R, Traber M (2008) Women and smokers have elevated urinary F(2)-isoprostane metabolites: a novel extraction and LC-MS methodology. Lipids 43(10):925–936

Morrow JD et al (1995) Increase in circulating products of lipid peroxidation (F2-isoprostanes) in smokers. Smoking as a cause of oxidative damage. N Engl J Med 332(18):1198–1203

Reilly M et al (1996) Modulation of oxidant stress in vivo in chronic cigarette smokers. Circulation 94(1):19–25

Collaboration HS (2002) Homocysteine and risk of ischemic heart disease and stroke. J Am Med Assoc 288(16):2015–2022

Woo KS et al (1997) Hyperhomocyst(e)inemia is a risk factor for arterial endothelial dysfunction in humans. Circulation 96(8):2542–2544

Miller JW et al (1994) Vitamin B-6 deficiency vs folate deficiency: comparison of responses to methionine loading in rats. Am J Clin Nutr 59(5):1033–1039

Di Minno G et al (1993) Abnormally high thromboxane biosynthesis in homozygous homocystinuria. Evidence for platelet involvement and probucol-sensitive mechanism. J Clin Investig 92(3):1400–1406

Davi G et al (2001) Oxidative stress and platelet activation in homozygous homocystinuria. Circulation 104(10):1124–1128

Durand P, Lussier-Cacan S, Blache D (1997) Acute methionine load-induced hyperhomocysteinemia enhances platelet aggregation, thromboxane biosynthesis, and macrophage-derived tissue factor activity in rats. FASEB J 11(13):1157–1168

Bonaa KH et al (2006) Homocysteine lowering and cardiovascular events after acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 354(15):1578–1588

Lonn E et al (2006) Homocysteine lowering with folic acid and B vitamins in vascular disease. N Engl J Med 354(15):1567–1577

Csordas A et al (2008) An evaluation of the clinical evidence on the role of inflammation and oxidative stress in smoking-mediated cardiovascular disease. Biomark Insights 3:127–139

Barden A et al (2011) The effects of oxidation products of arachidonic acid and n3 fatty acids on vascular and platelet function. Free Radic Res 45(4):469–476

Kinsella BT, O’Mahony DJ, Fitzgerald GA (1997) The human thromboxane A2 receptor alpha isoform (TP alpha) functionally couples to the G proteins Gq and G11 in vivo and is activated by the isoprostane 8-epi prostaglandin F2 alpha. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 281(2):957–964

Pfister SL, Nithipatikom K, Campbell WB (2011) Role of superoxide and thromboxane receptors in acute angiotensin II-induced vasoconstriction of rabbit vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300(6):H2064–H2071

Morrow JD, Roberts LJ 2nd (1996) The isoprostanes. Current knowledge and directions for future research. Biochem Pharmacol 51(1):1–9

Csiszar A et al (2002) Oxidative stress-induced isoprostane formation may contribute to aspirin resistance in platelets. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids 66(5–6):557–558

Bousser MG et al (2009) Rationale and design of a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group study of terutroban 30 mg/day versus aspirin 100 mg/day in stroke patients: the prevention of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events of ischemic origin with terutroban in patients with a history of ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (PERFORM) study. Cerebrovasc Dis 27(5):509–518

Santilli F, Mucci L, Davi G (2010) TP receptor activation and inhibition in atherothrombosis: the paradigm of diabetes mellitus. Intern Emerg Med 6(3):203–212

Egan KM et al (2005) Cyclooxygenases, thromboxane, and atherosclerosis: plaque destabilization by cyclooxygenase-2 inhibition combined with thromboxane receptor antagonism. Circulation 111(3):334–342

Prediman KS (2003) Mechanisms of plaque vulnerability and rupture. J Am Coll Cardiol 41(4, Supplement):S15–S22

Seet RCS et al (2011) Biomarkers of oxidative damage in cigarette smokers: which biomarkers might reflect acute versus chronic oxidative stress? Free Radical Biol Med 50(12):1787–1793

Nie D et al (2000) Eicosanoid regulation of angiogenesis: role of endothelial arachidonate 12-lipoxygenase. Blood 95(7):2304–2311

Terres W, Becker P, Rosenberg A (1994) Changes in cardiovascular risk profile during the cessation of smoking. Am J Med 97(3):242–249

Alberti KGMM et al (2009) Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome. Circulation 120(16):1640–1645

The Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration (2010) Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 375(9733):2215–2222

Reaven GM (2011) Relationships among insulin resistance, type 2 diabetes, essential hypertension, and cardiovascular disease: similarities and differences. J Clin Hypertens 13(4):238–243

Shoelson SE, Goldfine AB (2009) Getting away from glucose: fanning the flames of obesity-induced inflammation. Nat Med 15(4):373–374

Razani B, Semenkovich CF (2009) Getting away from glucose: stop sugarcoating diabetes. Nat Med 15(4):372–373

Zoungas S et al (2010) Severe hypoglycemia and risks of vascular events and death. N Engl J Med 363(15):1410–1418

Osorio J (2010) Diabetes: severe hypoglycemia associated with risk of vascular events and death. Nat Rev Cardiol 7(12):666

Bridges JM et al (1965) An effect of d-glucose on platelet stickiness. Lancet 1(7376):75–77

Vinik AI et al (2001) Platelet dysfunction in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 24(8):1476–1485

Gross ER et al (2003) Reactive oxygen species modulate coronary wall shear stress and endothelial function during hyperglycemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 284(5):H1552–H1559

Shinomiya K et al (2002) A role of oxidative stress-generated eicosanoid in the progression of arteriosclerosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus model rats. Hypertens Res 25(1):91–98

Niedowicz D, Daleke D (2005) The role of oxidative stress in diabetic complications. Cell Biochem Biophys 43(2):289–330

Davi G et al (1990) Thromboxane biosynthesis and platelet function in type II diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 322(25):1769–1774

Tang WH et al (2011) Glucose and collagen regulate human platelet activity through aldose reductase induction of thromboxane. J Clin Investig 121(11):4462–4476

Davi G et al (1999) In vivo formation of 8-iso-prostaglandin f2alpha and platelet activation in diabetes mellitus: effects of improved metabolic control and vitamin E supplementation. Circulation 99(2):224–229

Davi G et al (1997) Enhanced thromboxane biosynthesis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Chronic Obstructive Bronchitis and Haemostasis Study Group. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156(6):1794–1799

Santilli F, Mucci L, Davi G (2011) TP receptor activation and inhibition in atherothrombosis: the paradigm of diabetes mellitus. Intern Emerg Med 6(3):203–212

Santilli F et al (2006) Thromboxane-dependent CD40 ligand release in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol 47(2):391–397

Levy RL, White PD (1946) Overweight; its prognostic significance in relation to hypertension and cardiovascular-renal diseases. J Am Med Assoc 131:951–953

Graziani F et al (2011) Thromboxane production in morbidly obese subjects. Am J Cardiol 107(11):1656–1661

Warlow CP et al (1972) Platelet adhesiveness, coagulation, and fibrinolytic activity in obesity. J Clin Pathol 25(6):484–486

Jensen G et al (1991) Risk factors for acute myocardial infarction in Copenhagen, II: smoking, alcohol intake, physical activity, obesity, oral contraception, diabetes, lipids, and blood pressure. Eur Heart J 12(3):298–308

Komukai K et al (2011) Impact of body mass index on clinical outcome in patients hospitalized with congestive heart failure. Circ J 76(1):145–151

Curtis JP et al (2005) The obesity paradox: body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 165(1):55–61

Barbarroja N et al (2010) The obese healthy paradox: is inflammation the answer? Biochem J 430(1):141–149

Festa A et al (2000) Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: The Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Circulation 102(1):42–47

Lee DC et al (2011) Long-term effects of changes in cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men: the aerobics center longitudinal study. Circulation 124(23):2483–2490

Nikolaidis MG, Kyparos A, Vrabas IS (2011) F-isoprostane formation, measurement and interpretation: the role of exercise. Prog Lipid Res 50(1):89–103

Downing J, Balady GJ (2011) The role of exercise training in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 58(6):561–569

Reilly MP et al (1998) Increased formation of distinct F2 isoprostanes in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 98(25):2822–2828

Davi G et al (1992) Increased thromboxane biosynthesis in type IIa hypercholesterolemia. Circulation 85(5):1792–1798

Cyrus T, Ding T, Pratico D (2009) Expression of thromboxane synthase, prostacyclin synthase and thromboxane receptor in atherosclerotic lesions: correlation with plaque composition. Atherosclerosis 208(2):376–381

Goldstein JL et al (1985) Receptor-mediated endocytosis: concepts emerging from the LDL receptor system. Annu Rev Cell Biol 1:1–39

Siess W (2006) Platelet interaction with bioactive lipids formed by mild oxidation of low-density lipoprotein. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb 35(3–4):292–304

Ishigaki Y et al (2008) Impact of plasma oxidized low-density lipoprotein removal on atherosclerosis. Circulation 118(1):75–83

Puccetti L et al (2011) Effects of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin on thromboxane-dependent platelet activation and oxidative stress in hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 214(1):122–128

Santos-Gallego C, Giannarelli C, Badimón J (2011) Experimental models for the investigation of high-density lipoprotein-mediated cholesterol efflux. Curr Atheroscler Rep 13(3):266–276

Proudfoot JM et al (2009) HDL is the major lipoprotein carrier of plasma F2-isoprostanes. J Lipid Res 50(4):716–722

Waksman R et al (2010) A first-in-man, randomized, placebo-controlled study to evaluate the safety and feasibility of autologous delipidated high-density lipoprotein plasma infusions in patients with acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol 55(24):2727–2735

Cottin SC, Sanders TA, Hall WL (2011) The differential effects of EPA and DHA on cardiovascular risk factors. Proc Nutr Soc 70(2):215–231

Mas E et al (2010) The omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA decrease plasma F(2)-isoprostanes: results from two placebo-controlled interventions. Free Radic Res 44(9):983–990

Guillot N et al (2008) Effects of docosahexaenoic acid on some megakaryocytic cell gene expression of some enzymes controlling prostanoid synthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 372(4):924–928

Vericel E et al (2003) Pro- and antioxidant activities of docosahexaenoic acid on human blood platelets. J Thromb Haemost 1(3):566–572

Dombrowsky H et al (2011) Ingestion of (n-3) fatty acids augments basal and platelet activating factor-induced permeability to dextran in the rat mesenteric vascular bed. J Nutr 141(9):1635–1642

Wada M et al (2007) Enzymes and receptors of prostaglandin pathways with arachidonic acid-derived versus eicosapentaenoic acid-derived substrates and products. J Biol Chem 282(31):22254–22266

Marcelin G, Chua S Jr (2010) Contributions of adipocyte lipid metabolism to body fat content and implications for the treatment of obesity. Curr Opin Pharmacol 10(5):588–593

Enerbäck S (2009) The origins of brown adipose tissue. N Engl J Med 360(19):2021–2023

Raclot T et al (1997) Selective release of human adipocyte fatty acids according to molecular structure. Biochem J 324(Pt 3):911–915

Vassaux G et al (1992) Differential response of preadipocytes and adipocytes to prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2: physiological implications. Endocrinology 131(5):2393–2398

Jaworski K et al (2009) AdPLA ablation increases lipolysis and prevents obesity induced by high-fat feeding or leptin deficiency. Nat Med 15(2):159–168

Vegiopoulos A et al (2010) Cyclooxygenase-2 controls energy homeostasis in mice by de novo recruitment of brown adipocytes. Science 328(5982):1158–1161

Carmen GY, Víctor SM (2006) Signalling mechanisms regulating lipolysis. Cell Signal 18(4):401–408

Fain JN et al (2004) Comparison of the release of adipokines by adipose tissue, adipose tissue matrix, and adipocytes from visceral and subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissues of obese humans. Endocrinology 145(5):2273–2282

Alexandru N, Popov D, Georgescu A (2011) Platelet dysfunction in vascular pathologies and how can it be treated. Thromb Res 129(2):116–126

Zuern CS, Lindemann S Gawaz M (2009) Platelet function and response to aspirin: gender-specific features and implications for female thrombotic risk and management. Semin Thromb Hemost 35(3):295–306

Park B-J et al (2012) The relationship of platelet count, mean platelet volume with metabolic syndrome according to the criteria of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists: a focus on gender differences. Platelets 23(1):45–50

Hamet P et al (1985) Abnormalities of platelet function in hypertension and diabetes. Hypertension 7(6 Pt 2):II135–II142

Kjeldsen SE et al (1991) The epinephrine-blood platelet connection with special reference to essential hypertension. Am Heart J 122(1 Pt 2):330–336

Wei AH et al (2009) New insights into the haemostatic function of platelets. Br J Haematol 147(4):415–430

Roethig HJ et al (2010) Short term effects of reduced exposure to cigarette smoke on white blood cells, platelets and red blood cells in adult cigarette smokers. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 57(2–3):333–337

Padmavathi P et al (2010) Smoking-induced alterations in platelet membrane fluidity and Na+/K+-ATPase activity in chronic cigarette smokers. J Atheroscler Thromb 17(6):619–627

Neubauer H et al (2009) Upregulation of platelet CD40, CD40 ligand (CD40L) and P-Selectin expression in cigarette smokers: a flow cytometry study. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 20(8):694–698

Vazzana N et al (2012) Diabetes mellitus and thrombosis. Thrombosis Res 129(3):371–377

Mylotte D et al (2012) Platelet reactivity in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a comparative analysis with survivors of myocardial infarction and the role of glycaemic control. Platelets. doi:10.3109/09537104.2011.634932

Murakami T et al (2007) Impact of weight reduction on production of platelet-derived microparticles and fibrinolytic parameters in obesity. Thromb Res 119(1):45–53

De Pergola G et al (2008) sP-selectin plasma levels in obesity: association with insulin resistance and related metabolic and prothrombotic factors. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 18(3):227–232

Anfossi G, Russo I, Trovati M (2009) Platelet dysfunction in central obesity. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 19(6):440–449

Trip MD et al (1990) Platelet hyperreactivity and prognosis in survivors of myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 322(22):1549–1554

Huo Y et al (2003) Circulating activated platelets exacerbate atherosclerosis in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Nat Med 9(1):61–67

Lievens D et al (2010) Platelet CD40L mediates thrombotic and inflammatory processes in atherosclerosis. Blood 116(20):4317–4327

Giannini S et al (2011) Interaction with damaged vessel wall in vivo in humans induces platelets to express CD40L resulting in endothelial activation with no effect of aspirin intake. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300(6):H2072–H2079

Dawood BB, Wilde J, Watson SP (2007) Reference curves for aggregation and ATP secretion to aid diagnose of platelet-based bleeding disorders: effect of inhibition of ADP and thromboxane A2 pathways. Platelets 18(5):329–345

Smyth EM (2010) Thromboxane and the thromboxane receptor in cardiovascular disease. Clin Lipidol 5(2):209–219

Wilson SJ et al (2009) Activation-dependent stabilization of the human thromboxane receptor: role of reactive oxygen species. J Lipid Res 50(6):1047–1056

Zhang M et al (2008) Thromboxane receptor activates the AMP-activated protein kinase in vascular smooth muscle cells via hydrogen peroxide. Circ Res 102(3):328–337

Kobzar G, Mardla V, Samel N (2011) Short-term exposure of platelets to glucose impairs inhibition of platelet aggregation by cyclooxygenase inhibitors. Platelets 22(5):338–344

Kobayashi T et al (2004) Roles of thromboxane A(2) and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 114(6):784–794

Pakala R, Willerson JT, Benedict CR (1997) Effect of serotonin, thromboxane A2, and specific receptor antagonists on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circulation 96(7):2280–2286

Yun DH et al (2009) Thromboxane A(2) modulates migration, proliferation, and differentiation of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Exp Mol Med 41(1):17–24

Daniel TO et al (1999) Thromboxane A2 is a mediator of cyclooxygenase-2-dependent endothelial migration and angiogenesis. Cancer Res 59(18):4574–4577

Iyu D et al (2010) The role of prostanoid receptors in mediating the effects of PGE(2) on human platelet function. Platelets 21(5):329–342

Iyu D et al (2010) PGE1 and PGE2 modify platelet function through different prostanoid receptors. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 94(1–2):9–16

Fabre JE et al (2001) Activation of the murine EP3 receptor for PGE2 inhibits cAMP production and promotes platelet aggregation. J Clin Invest 107(5):603–610

Smith JP et al (2010) PGE2 decreases reactivity of human platelets by activating EP2 and EP4. Thromb Res 126(1):e23–e29

Wang M et al (2006) Deletion of microsomal prostaglandin E synthase-1 augments prostacyclin and retards atherogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103(39):14507–14512

Philipose S et al (2010) The prostaglandin E2 Receptor EP4 is expressed by human platelets and potently inhibits platelet aggregation and thrombus formation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30(12):2416–2423

Kuriyama S et al (2010) Selective activation of the prostaglandin E2 receptor subtype EP2 or EP4 leads to inhibition of platelet aggregation. Thromb Haemost 104(4):796–803

Petrucci G et al (2010) Prostaglandin E2 differentially modulates human platelet function through the prostanoid EP2 and EP3 receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 336(2):391–402

Schober LJ et al (2011) The role of PGE(2) in human atherosclerotic plaque on platelet EP(3) and EP(4) receptor activation and platelet function in whole blood. J Thromb Thrombolysis 32(2):158–166

Rolland P et al (1984) Alteration in prostacyclin and prostaglandin E2 production. Correlation with changes in human aortic atherosclerotic disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 4(1):70–78

Ridker PM et al (2003) C-Reactive Protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events. Circulation 107(3):391–397

Pepys MB, Hirschfield GM (2003) C-reactive protein: a critical update. J Clin Investig 111(12):1805–1812

Blankenberg S et al (2010) Contribution of 30 biomarkers to 10-year cardiovascular risk estimation in 2 population cohorts: the MONICA, risk, genetics, archiving, and monograph (MORGAM) biomarker project. Circulation 121(22):2388–2397

Ridker PM et al (2002) Comparison of C-reactive protein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in the prediction of first cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med 347(20):1557–1565

Koenig W et al (1999) C-reactive protein, a sensitive marker of inflammation, predicts future risk of coronary heart disease in initially healthy middle-aged men : results from the MONICA (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease) Augsburg Cohort Study, 1984 to 1992. Circulation 99(2):237–242

Freeman DJ et al (2002) C-reactive protein is an independent predictor of risk for the development of diabetes in the West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study. Diabetes 51(5):1596–1600

Eisenhardt SU et al (2009) C-reactive protein: how conformational changes influence inflammatory properties. Cell Cycle 8(23):3885–3892

Thompson D, Pepys MB, Wood SP (1999) The physiological structure of human C-reactive protein and its complex with phosphocholine. Structure 7(2):169–177

Eisenhardt SU, Habersberger J, Peter K (2009) Monomeric C-reactive protein generation on activated platelets: the missing link between inflammation and atherothrombotic risk. Trends Cardiovasc Med 19(7):232–237

Fiedel BA, Simpson RM, Gewurz H (1982) Effects of C-reactive protein (Crp) on platelet function. Ann N Y Acad Sci 389(1):263–273

Grad E et al (2009) Aspirin reduces the prothrombotic activity of C-reactive protein. J Thromb Haemost 7(8):1393–1400

Gao XR et al (2009) Efficacy of different doses of aspirin in decreasing blood levels of inflammatory markers in patients with cardiovascular metabolic syndrome. J Pharm Pharmacol 61(11):1505–1510

Makhoul Z et al (2011) Associations of obesity with triglycerides and C-reactive protein are attenuated in adults with high red blood cell eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids. Eur J Clin Nutr 65(7):808–817

Peters-Golden M, Henderson WR Jr (2007) Leukotrienes. N Engl J Med 357(18):1841–1854

Helgadottir A et al (2004) The gene encoding 5-lipoxygenase activating protein confers risk of myocardial infarction and stroke. Nat Genet 36(3):233–239

Mechiche H et al (2004) Characterization of cysteinyl leukotriene receptors on human saphenous veins: antagonist activity of montelukast and its metabolites. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 43(1):113–120

Vinten-Johansen J (2004) Involvement of neutrophils in the pathogenesis of lethal myocardial reperfusion injury. Cardiovasc Res 61(3):481–497

Carnini C et al (2011) Synthesis of cysteinyl leukotrienes in human endothelial cells: subcellular localization and autocrine signaling through the CysLT2 receptor. FASEB J 25(10):3519–3528

Capra V et al (2003) Involvement of prenylated proteins in calcium signaling induced by LTD4 in differentiated U937 cells. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat 71(3–4):235–251

Hui Y et al (2004) Directed vascular expression of human cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor modulates endothelial permeability and systemic blood pressure. Circulation 110(21):3360–3366

Jiang W et al (2008) Endothelial cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor expression mediates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Pathol 172(3):592–602

Yu GL et al (2005) Montelukast, a cysteinyl leukotriene receptor-1 antagonist, dose- and time-dependently protects against focal cerebral ischemia in mice. Pharmacology 73(1):31–40

Sener G et al (2006) Montelukast protects against renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in rats. Pharmacol Res 54(1):65–71

Back M et al (2005) Leukotriene B4 signaling through NF-kappaB-dependent BLT1 receptors on vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis and intimal hyperplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(48):17501–17506

Subbarao K et al (2004) Role of leukotriene B4 receptors in the development of atherosclerosis: potential mechanisms. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24(2):369–375

Heller EA et al (2005) Inhibition of atherogenesis in BLT1-deficient mice reveals a role for LTB4 and BLT1 in smooth muscle cell recruitment. Circulation 112(4):578–586

Bäck M (2009) Leukotriene signaling in atherosclerosis and ischemia. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 23(1):41–48

Aiello RJ et al (2002) Leukotriene B4 receptor antagonism reduces monocytic foam cells in mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 22(3):443–449

Kaetsu Y et al (2007) Role of cysteinyl leukotrienes in the proliferation and the migration of murine vascular smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro. Cardiovasc Res 76(1):160–166

Jawien J et al (2008) The effect of montelukast on atherogenesis in apoE/LDLR-double knockout mice. J Physiol Pharmacol 59(3):633–639

Mueller CF et al (2008) Multidrug resistance protein-1 affects oxidative stress, endothelial dysfunction, and atherogenesis via leukotriene C4 export. Circulation 117(22):2912–2918

Opper C et al (1995) Increased number of high sensitive platelets in hypercholesterolemia, cardiovascular diseases, and after incubation with cholesterol. Atherosclerosis 113(2):211–217

Matsuoka T et al (2000) Prostaglandin D2 as a mediator of allergic asthma. Science 287(5460):2013–2017

Eguchi Y et al (1997) Expression of lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase (beta-trace) in human heart and its accumulation in the coronary circulation of angina patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94(26):14689–14694

Taba Y et al (2000) Fluid shear stress induces lipocalin-type prostaglandin D(2) synthase expression in vascular endothelial cells. Circ Res 86(9):967–973

Hirawa N et al (2002) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin d synthase in essential hypertension. Hypertension 39(2 Pt 2):449–454

Inoue T et al (2008) Lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase is a powerful biomarker for severity of stable coronary artery disease. Atherosclerosis 201(2):385–391

Miwa Y et al (2008) Association of serum lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase levels with subclinical atherosclerosis in untreated asymptomatic subjects. Hypertens Res 31(10):1931–1939

Sawyer N et al (2002) Molecular pharmacology of the human prostaglandin D2 receptor, CRTH2. Br J Pharmacol 137(8):1163–1172

Bohm E et al (2004) 11-Dehydro-thromboxane B2, a stable thromboxane metabolite, is a full agonist of chemoattractant receptor-homologous molecule expressed on TH2 cells (CRTH2) in human eosinophils and basophils. J Biol Chem 279(9):7663–7670

Murray JJ et al (1986) Release of prostaglandin D2 into human airways during acute antigen challenge. N Engl J Med 315(13):800–804

Tsukada T et al (1986) Immunocytochemical analysis of cellular components in atherosclerotic lesions. Use of monoclonal antibodies with the Watanabe and fat-fed rabbit. Arteriosclerosis 6(6):601–613

Nagoshi H et al (1998) Prostaglandin D2 inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 82(2):204–209

Tokudome S et al (2009) Glucocorticoid protects rodent hearts from ischemia/reperfusion injury by activating lipocalin-type prostaglandin D synthase-derived PGD2 biosynthesis. J Clin Invest 119(6):1477–1488

Baigent C et al (1998) ISIS-2: 10-year survival among patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction in randomised comparison of intravenous streptokinase, oral aspirin, both, or neither. BMJ 316(7141):1337

Juni P et al (2004) Risk of cardiovascular events and rofecoxib: cumulative meta-analysis. Lancet 364(9450):2021–2029

Kobayashi T et al (2004) Roles of thromboxane A2 and prostacyclin in the development of atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Clin Investig 114(6):784–794

Offermanns S (2006) Activation of platelet function through G protein-coupled receptors. Circ Res 99(12):1293–1304

Poredos P, Jezovnik MK (2011) Dyslipidemia, statins, and venous thromboembolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 37(8):897–902

Raychowdhury MK et al (1994) Alternative splicing produces a divergent cytoplasmic tail in the human endothelial thromboxane A2 receptor. J Biol Chem 269(30):19256–19261

Hirata T et al (1996) Two thromboxane A2 receptor isoforms in human platelets. Opposite coupling to adenylyl cyclase with different sensitivity to Arg60 to Leu mutation. J Clin Invest 97(4):949–956

Parent JL et al (1999) Internalization of the TXA2 receptor alpha and beta isoforms. Role of the differentially spliced COOH terminus in agonist-promoted receptor internalization. J Biol Chem 274(13):8941–8948

Wikström K et al (2008) Differential regulation of RhoA-mediated signaling by the TP[alpha] and TP[beta] isoforms of the human thromboxane A2 receptor: Independent modulation of TP[alpha] signaling by prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Cell Signal 20(8):1497–1512

Miggin SM, Kinsella BT (2002) Regulation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase cascades by alpha- and beta-isoforms of the human thromboxane A2 receptor. Mol Pharmacol 61(4):817–831

An S et al (1994) Isoforms of the EP3 subtype of human prostaglandin E2 receptor transduce both intracellular calcium and cAMP signals. Biochemistry 33(48):14496–14502

Liang Y et al (2008) Identification and pharmacological characterization of the prostaglandin FP receptor and FP receptor variant complexes. Br J Pharmacol 154(5):1079–1093

Wilson SJ et al (2004) Dimerization of the human receptors for prostacyclin and thromboxane facilitates thromboxane receptor-mediated cAMP generation. J Biol Chem 279(51):53036–53047

Wilson SJ et al (2007) Regulation of thromboxane receptor trafficking through the prostacyclin receptor in vascular smooth muscle cells—role of receptor heterodimerization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27(2):290–296

Ibrahim S et al (2010) Dominant negative actions of human prostacyclin receptor variant through dimerization: implications for cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30(9):1802–1809

Wilson SJ et al (2007) Heterodimerization of the alpha and beta isoforms of the human thromboxane receptor enhances isoprostane signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 352(2):397–403

Parhamifar L et al (2010) Ligand-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of cysteinyl leukotriene receptor 1 triggers internalization and signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. PLoS One 5(12):e14439

Maekawa A et al (2009) GPR17 is a negative regulator of the cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor response to leukotriene D4. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106(28):11685–11690

Maekawa A et al (2010) GPR17 regulates immune pulmonary inflammation induced by house dust mites. J Immunol 185(3):1846–1854

Patrignani P et al (2008) Differential association between human prostacyclin receptor polymorphisms and the development of venous thrombosis and intimal hyperplasia: a clinical biomarker study. Pharmacogenet Genomics 18(7):611–620

Ibrahim S et al (2010) Dominant negative actions of human prostacyclin receptor variant through dimerization: implications for cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 30(9):1802–1809

Stitham J, Stojanovic A, Hwa J (2002) Impaired receptor binding and activation associated with a human prostacyclin receptor polymorphism. J Biol Chem 277(18):15439–15444

Stitham J et al (2011) Comprehensive biochemical analysis of rare prostacyclin receptor variants study of association of signaling with coronary artery obstruction. J Biol Chem 286(9):7060–7069

Stitham J et al (2010) Comprehensive biochemical analysis of rare prostacyclin receptor variants: study of association of signaling with coronary artery obstruction. J Biol Chem 286(9):7060–7069

Mumford AD et al (2010) A novel thromboxane A2 receptor D304N variant that abrogates ligand binding in a patient with a bleeding diathesis. Blood 115(2):363–369

Thompson MD et al (2006) A functional G300S variant of the cysteinyl leukotriene 1 receptor is associated with atopy in a Tristan da Cunha isolate. Pharmacogenet Genomics 17(7):539–549

Pillai SG et al (2004) A coding polymorphism in the CYSLT2 receptor with reduced affinity to LTD4 is associated with asthma. Pharmacogenetics 14(9):627–633

Thompson MD et al (2003) A cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor variant is associated with atopy in the population of Tristan da Cunha. Pharmacogenetics 13(10):641–649

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for our outstanding eicosanoid centric colleagues who have collaborated with us in our studies on eicosanoids and cardiovascular disease. In pursuing our studies, we are also grateful for generous funding from NIH (NHLBI) and the American Heart Association. This review is dedicated to the memory of Har Gobind Khorana (1922–2011) a brilliant scientist and mentor without whom many of these studies would not have been possible.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gleim, S., Stitham, J., Tang, W.H. et al. An eicosanoid-centric view of atherothrombotic risk factors. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 69, 3361–3380 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-012-0982-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-012-0982-9