Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to compare acute changes of non-esterified fatty acids (NEFA) in relation to beta cell function (BCF) and insulin resistance in obese patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) who underwent laparoscopic gastric bypass (GBP), laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (SG) or very low calorie diet (VLCD).

Methods

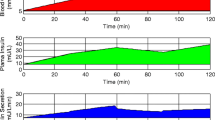

In a non-randomised study, fasting plasma samples were collected from 38 obese patients with T2D, matched for age, body mass index (BMI) and glycaemic control, who underwent GBP (11) or SG (14) or VLCD (13). Samples were collected the day before and 3 days after the intervention, during a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test. Glucose, insulin, c-peptide, glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP) were measured, and individual NEFAs were measured using a triple-quadrupole liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). BCF by mathematical modelling and insulin resistance were estimated.

Results

Palmitic acid significantly decreased after each intervention. Monounsaturated/polyunsaturated ratio (MUFA/PUFA) and unsaturated/saturated fat ratios increased after each intervention. BCF was improved only after VLCD. Linoleic acid was positively correlated with total insulin secretion (p = 0.03). Glucose sensitivity correlated with palmitic acid (p = 0.01), unsaturated/saturated ratio (p = 0.0008) and MUFA/PUFA (p = 0.009). HOMA-IR correlated with stearic acid (p = 0.03), unsaturated/saturated ratio (p = 0.005) and MUFA/PUFA (p = 0.009). GIP AUC0–120 correlated with stearic acid (p = 0.04), but not GLP-1.

Conclusions

GBP, SG and VLCD have similar acute effects on decreasing palmitic acid. Several NEFAs correlated with BCF parameters and HOMA-IR.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abbasi F, McLaughlin T, Lamendola C, et al. Insulin regulation of plasma free fatty acid concentrations is abnormal in healthy subjects with muscle insulin resistance. Metabolism. 2000;49(2):151–4.

McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Lamendola C, et al. Metabolic changes following sibutramine-assisted weight loss in obese individuals: role of plasma free fatty acids in the insulin resistance of obesity. Metabolism. 2001;50(7):819–24.

Boden G. Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and NIDDM. Diabetes. 1997;46(1):3–10.

Boden G. Obesity and free fatty acids. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2008;37(3):635–46.

Vessby B. Dietary fat, fatty acid composition in plasma and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14(1):15–9.

Large V, Peroni O, Letexier D, et al. Metabolism of lipids in human white adipocyte. Diabetes & metabolism. 2004;30(4):294–309.

Stumvoll M, Jacob S. Multiple sites of insulin resistance: muscle, liver and adipose tissue. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes: official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 1999;107(2):107.

Carlson OD, David JD, Schrieder JM, et al. Contribution of nonesterified fatty acids to insulin resistance in the elderly with normal fasting but diabetic 2-hour postchallenge plasma glucose levels: the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Metabolism. 2007;56(10):1444–51.

Kashyap S, Belfort R, Gastaldelli A, et al. A sustained increase in plasma free fatty acids impairs insulin secretion in nondiabetic subjects genetically predisposed to develop type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2003;52(10):2461–74.

Stumvoll M, Goldstein BJ, van Haeften TW. Type 2 diabetes: principles of pathogenesis and therapy. Lancet. 2005;365(9467):1333–46.

Plourde CÉ, Grenier-Larouche T, Caron-Dorval D, et al. Biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch improves insulin sensitivity and secretion through caloric restriction. Obesity. 2014;22(8):1838–46.

Lim E, Hollingsworth K, Aribisala B, et al. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia. 2011;54(10):2506–14.

Goldrick R, Hirsch J. Serial studies on the metabolism of human adipose tissue. II. Effects of caloric restriction and refeeding on lipogenesis, and the uptake and release of free fatty acids in obese and nonobese individuals. J Clin Investig. 1964;43(9):1793.

Boden G. Effects of free fatty acids (FFA) on glucose metabolism: significance for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Experimental and clinical endocrinology & diabetes: official journal, German Society of Endocrinology [and] German Diabetes Association. 2003;111(3):121–4.

Kang Z, Deng Y, Zhou Y, et al. Pharmacological reduction of NEFA restores the efficacy of incretin-based therapies through GLP-1 receptor signalling in the beta cell in mouse models of diabetes. Diabetologia. 2013;56(2):423–33.

Karpe F, Dickmann JR, Frayn KN. Fatty acids, obesity, and insulin resistance: time for a reevaluation. Diabetes. 2011;60(10):2441–9.

Buchwald H, Estok R, Fahrbach K, et al. Weight and type 2 diabetes after bariatric surgery: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med. 2009;122(3):248–56. e5.

Kashyap SR, Gatmaitan P, Brethauer S, et al. Bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes: weighing the impact for obese patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2010;77(7):468–76.

Klein S, Mittendorfer B, Eagon JC, et al. Gastric bypass surgery improves metabolic and hepatic abnormalities associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(6):1564–72.

Risérus U, Willett WC, Hu FB. Dietary fats and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48(1):44–51.

Salinari S, Bertuzzi A, Asnaghi S, et al. First-phase insulin secretion restoration and differential response to glucose load depending on the route of administration in type 2 diabetic subjects after bariatric surgery. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(3):375–80.

Matthews D, Hosker J, Rudenski A, et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia. 1985;28(7):412–9.

Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA. Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(9):1462–70.

Stumvoll M, Gerich J. Clinical features of insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction and the relationship to type 2 diabetes. Clin Lab Med. 2001;21(1):31–51.

Mari A, Schmitz O, Gastaldelli A, et al. Meal and oral glucose tests for assessment of β-cell function: modeling analysis in normal subjects. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2002;283(6):E1159–E66.

Mari A, Tura A, Gastaldelli A, et al. Assessing insulin secretion by modeling in multiple-meal tests role of potentiation. Diabetes. 2002;51(suppl 1):S221–S6.

Tura A, Mari A, Winzer C, et al. Impaired β-cell function in lean normotolerant former gestational diabetic women. Eur J Clin Investig. 2006;36(1):22–8.

Santoro N, Caprio S, Giannini C, et al. Oxidized fatty acids: a potential pathogenic link between fatty liver and type 2 diabetes in obese adolescents? Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(2):383–9.

Toledo K, Aranda M, Asenjo S, et al. Unsaturated fatty acids and insulin resistance in childhood obesity. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27(5–6):503–10.

McGarry J, Dobbins R. Fatty acids, lipotoxicity and insulin secretion. Diabetologia. 1999;42(2):128–38.

Sako Y, Grill VE. A 48-hour lipid infusion in the rat time-dependently inhibits glucose-induced insulin secretion and B cell oxidation through a process likely coupled to fatty acid oxidation*. Endocrinology. 1990;127(4):1580–9.

Kelly A, Ryder J, Marlatt K, et al. Changes in inflammation, oxidative stress and adipokines following bariatric surgery among adolescents with severe obesity. Int J Obes. 2016;40:275–80.

Murri M, García-Fuentes E, García-Almeida JM, et al. Changes in oxidative stress and insulin resistance in morbidly obese patients after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2010;20(3):363–8.

Chait A, Kim F. Saturated fatty acids and inflammation: who pays the toll? Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30(4):692–3.

Ehses J, Meier D, Wueest S, et al. Toll-like receptor 2-deficient mice are protected from insulin resistance and beta cell dysfunction induced by a high-fat diet. Diabetologia. 2010;53(8):1795–806.

Hirabara SM, Curi R, Maechler P. Saturated fatty acid-induced insulin resistance is associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010;222(1):187–94.

Jové M, Planavila A, Laguna JC, et al. Palmitate-induced interleukin 6 production is mediated by protein kinase C and nuclear-factor κB activation and leads to glucose transporter 4 down-regulation in skeletal muscle cells. Endocrinology. 2005;146(7):3087–95.

Tiganis T. Reactive oxygen species and insulin resistance: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32(2):82–9.

Ma W, Wu JH, Wang Q, et al. Prospective association of fatty acids in the de novo lipogenesis pathway with risk of type 2 diabetes: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(1):153–63.

Shah M, Adams-Huet B, Brinkley L, et al. Lipid, glycemic, and insulin responses to meals rich in saturated, cis-monounsaturated, and polyunsaturated (n-3 and n-6) fatty acids in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(12):2993–8.

Grapov D, Adams SH, Pedersen TL, et al. Type 2 diabetes associated changes in the plasma non-esterified fatty acids, oxylipins and endocannabinoids. PLoS One. 2012;7(11):e48852.

Imamura S, Morioka T, Yamazaki Y, et al. Plasma polyunsaturated fatty acid profile and delta-5 desaturase activity are altered in patients with type 2 diabetes. Metabolism. 2014;63(11):1432–8.

Griffo E, Nosso G, Lupoli R, et al. Early improvement of postprandial lipemia after bariatric surgery in obese type 2 diabetic patients. Obes Surg. 2014;24(5):765–70.

Jørgensen NB, Dirksen C, Bojsen-Møller KN, et al. Exaggerated glucagon-like peptide 1 response is important for improved β-cell function and glucose tolerance after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2013;62(9):3044–52.

Rocca A, Brubaker P. Role of the vagus nerve in mediating proximal nutrient-induced glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion 1. Endocrinology. 1999;140(4):1687–94.

Nauck MA. Unraveling the science of incretin biology. Am J Med. 2009;122(6):S3–S10.

Isbell JM, Tamboli RA, Hansen EN, et al. The importance of caloric restriction in the early improvements in insulin sensitivity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(7):1438–42.

Burcelin R, Serino M, Cabou C. A role for the gut-to-brain GLP-1-dependent axis in the control of metabolism. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2009;9(6):744–52.

Hirasawa A, Tsumaya K, Awaji T, et al. Free fatty acids regulate gut incretin glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion through GPR120. Nat Med. 2005;11(1):90–4.

DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R. Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology. 1979;237(3):G214–G23.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Jens Henrik Jensen Academic Fellowship and Auckland A+ Research Trust.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the local ethics committee (Northern X Regional ethics committee), and all patients gave informed written consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

A Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Financial Support

We acknowledge financial support from the Faculty of Health and Environmental Sciences, Auckland University of Technology, and from Lottery Health Research and Maurice and Phyllis Paykel Trust for the LC-MS facility.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 17.8 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nemati, R., Lu, J., Tura, A. et al. Acute Changes in Non-esterified Fatty Acids in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Receiving Bariatric Surgery. OBES SURG 27, 649–656 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2323-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-016-2323-9