Abstract

Background

Heart failure patients have high 30-day hospital readmission rates. Interventions designed to prevent readmissions have had mixed success. Understanding heart failure home management through the patient’s experience may reframe the readmission “problem” and, ultimately, inform alternative strategies.

Objective

To understand patient and caregiver challenges to heart failure home management and perceived reasons for readmission.

Design

Observational qualitative study.

Participants

Heart failure patients were recruited from two hospitals and included those who were hospitalized for heart failure at least twice within 30 days and those who had been recently discharged after their first heart failure admission.

Approach

Open-ended, semi-structured interviews. Conclusions vetted using focus groups.

Key Results

Semi-structured interviews with 31 patients revealed a combination of physical and socio-emotional influences on patients’ home heart failure management. Major themes identified were home management as a struggle between adherence and adaptation, and hospital readmission as a rational choice in response to distressing symptoms. Patients identified uncertainty regarding recommendations, caused by unclear instructions and temporal incongruence between behavior and symptom onset. This uncertainty impaired their competence in making routine management decisions, resulting in a cycle of limit testing and decreasing adherence. Patients reported experiencing hopelessness and frustration in response to perceiving a deteriorating functional status. This led some to a cycle of despair characterized by worsening adherence and negative emotions. As these cycles progressed and distressing symptoms worsened, patients viewed the hospital as the safest place for recovery and not a “negative” outcome.

Conclusion

Cycles of limit testing and despair represent important patient-centered struggles in managing heart failure. The resulting distress and fear make readmission a rational choice for patients rather than a negative outcome. Interventions (e.g., palliative care) that focus on methods to address these patient-centered factors should be further studied rather than methods to reduce hospital readmissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Heart failure is a syndrome with high morbidity and mortality that places a substantial burden on patients, caregivers, and healthcare systems. More than 6.5 million people in the USA currently live with heart failure and projections estimate this number will rise to 8 million by 2030.1 While advances in therapies for heart failure have improved overall mortality, the physical symptoms and psychological distress associated with the syndrome lead to poor quality of life in patients and caregivers.2,3 Furthermore, the high costs associated with heart failure treatment, expected to reach $70 billion in the USA by 2030, remain a major concern for public health policy.1 Healthcare systems have been incentivized to reduce heart failure rehospitalizations by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services through financial penalties for high 30-day readmission rates.4

Interventions to reduce readmissions have targeted three main time periods: pre-discharge in the hospital, the transitional period between hospital discharge and stable outpatient management, and post-discharge as an outpatient.5,6 While these interventions have had mixed success, those that target the transitional period have shown the most promise.5,6,7 During the transitional period, patients must adapt their behaviors in order to put into effect new and challenging self-management techniques, and navigate a complex healthcare system at the same time. Interventions that include transition coaches, patient-centered discharge instructions, and provider continuity have been found to be the most effective.5,6 Yet, the most successful strategies have been difficult to adopt on a large scale given that many of them are resource-intensive and difficult to generalize to other environments.5 Perhaps most importantly, it remains unclear whether current interventions are targeting and improving the outcomes that are meaningful to patients.

Some of the shortcomings of previous interventions to reduce readmissions may stem from a misalignment of the ways in which healthcare providers, patients, and caregivers perceive heart failure, as well as differences in the outcomes they value.8 While multiple qualitative studies have explored this topic, most have assessed only the experience of managing heart failure at home or reasons for readmission.9,10,11,12,13 A major limitation to improving the management of heart failure is an incomplete understanding of the patient experience. Our study’s aim was to use qualitative methods to develop a conceptual framework for understanding patient perspectives on the interdependence between home management and rehospitalization. Such a framework will be useful to guide future quantitative research, intervention development, and selection of outcomes for intervention and measurement.

METHODS

We first used patient interviews to identify the challenges facing heart failure patients in their home management of the disease. We then used focus groups as a method of member checking (returning to the target population to discuss findings) and triangulation, a commonly used qualitative method to help improve internal validity.

Patient Interviews

We used purposive sampling to recruit two different groups of patients with heart failure to participate in a one-time, open-ended semi-structured interview: (1) patients with a readmission following a prior heart failure admission (readmission group) and (2) patients recently discharged from a heart failure admission (index admission group). The readmission group consisted of patients who had been readmitted for heart failure following at least one hospitalization in the preceding 30 days; these patients were interviewed in the hospital. The index admission group consisted of patients who had been recently discharged following their first admission with a diagnosis of heart failure; these patients were interviewed at home by telephone within 6 weeks of discharge. We chose these two patient groups to identify a more complete perspective of the challenges to home management that patients face, both the experiences that readmitted patients had in the days leading to their readmission and the experiences that discharged patients had soon after returning home. We planned to recruit participants until saturation was reached with a minimum goal of 30 interviews (15 patients in each group).

Patients were identified by admission diagnostic code in the electronic health record and recruited in person from two sites, the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, between October 2013 and December 2013. Interviews were conducted by two research coordinators from the Mixed Methods Research Lab (MMRL) under the supervision of FB. The interview guide (see Appendix I in ESM) was developed using content areas and language informed by our previous qualitative work in this area.8 Questions addressed the experience of living with heart failure and perceptions about managing heart failure at home. Standardized probes were included to maintain consistency across interviews.

Focus Groups

Focus group interview guides (see Appendices II and III in ESM) were built using the preliminary conclusions derived from the individual interviews. After completion of the individual interviews, a new group of patients and caregivers was recruited to participate in two focus groups of heart failure patients and two focus groups of caregivers to internally validate the results of our interviews through member checking and triangulation. Focus group patients were identified through the electronic health record, recruited during clinic visits, and asked to identify their primary caregiver who was also recruited. Focus groups were facilitated by a research coordinator and FB.

Analyses

We used a grounded theory approach to analysis. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded, transcribed, de-identified, and entered into NVivo 10.0 for coding and analysis. We created a codebook by jointly conducting a line-by-line review of three transcripts of patient interviews and iteratively identifying and applying codes to text. Once the list of codes was finalized, we added explicit definitions and decision rules for use of each code. MMRL research staff coded each interview independently. Teams of coders met with the investigator team, conducted inter-rater reliability checks, and discussed any discrepancies in coding until consensus was reached. This process was done until all 31 interview transcripts were coded. The content of each code was then sub-coded into more specific categories, summarized, and examined for patterns and themes.

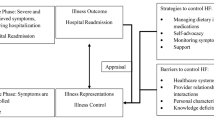

Focus group transcripts were coded using the same codebook to facilitate comparison between the interview findings and the perceptions of participants in the focus groups. Themes were divided into subthemes and were then used to develop the conceptual framework presented in Figure 1, which was reviewed by our patient partner (TG). The University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board approved this study and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Conceptual Framework. Tension between adherence to and adaptation of recommendations is a challenge to home heart failure management. This process is fueled by a cycle of limit testing and a cycle of despair. As the cycles progress and symptoms worsen, patients view readmission as a rational choice.

RESULTS

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 31 patients (mean age, 59 years; Table 1). All patients with an index admission (n = 15) had a prior outpatient diagnosis of heart failure. Data saturation was reached after approximately 12 interviews with each group; however, data collection continued until 31 participants were recruited to confirm saturation. These interviews revealed a combination of physical and socio-emotional influences on patients’ home management ability and decisions for readmission. We confirmed our interview findings with new participants who had experienced living with or caring for someone with heart failure, by presenting our preliminary findings (see Appendices II and III in ESM) to four focus groups with 19 heart failure patients and two focus groups with nine of their family caregivers (Table 2). Two caregivers were not able to attend one of the focus groups and were individually interviewed. Two main themes, discussed further below, emerged from these interview data: home management as a struggle between adherence and adaptation, and hospital readmission as a rational choice in response to distressing symptoms.

Adherence vs. Adaptation

Although many discharge instructions provide guidelines for home management, patients described adapting—as opposed to adhering to—these recommendations. Adaptation was a dynamic process through which patients modified their home management behaviors to optimize the balance between adherence with medical recommendations and competing factors such as personal circumstances, values, and emotions. Six main factors that influenced the process of adaptation were identified: (1) uncertainty regarding recommendations caused by inadequate or vague instructions; (2) temporal incongruence between behavior and symptom onset; (3) comorbidities; (4) socio-economic factors; (5) hopelessness from treatment failure despite good adherence; and (6) a strong emotional response to the limitations brought about by heart failure and its management. The degree to which a patient experienced these factors determined the extent to which patients adapted medical recommendations in order to accommodate personal reactions and medical limitations while minimizing physical symptoms. The following section details each of the above-mentioned factors. Supporting quotations are presented in Tables 3 and 4 with some quotes highlighted in the text below.

Uncertainty Regarding Recommendations

Patients reported challenges with routine management decisions caused by vague or insufficient instructions regarding diet, fluid management, and physical activity. While some patients felt they had a good understanding of heart failure, others felt they would benefit from more knowledge about the disease process and anticipatory guidance. In some, this uncertainty led to an intolerable burden in which they felt that making the wrong decision would put their lives in danger.

So I think it’s just a gripping fear “Can I do this? Can I do that?” And of course you don’t want to call your doctor even at 2:00 in the afternoon, can I take a five-mile hike? But I don’t think it’s ever been clearly defined to me what they mean. That would be very helpful because I probably did what they didn’t want me to do. (female, post-index admission)

Temporal Incongruence Between Behaviors and Symptom Onset

Patients reported difficulties identifying immediate physical effects when not adhering strictly to recommendations, particularly in relation to medications, diet, and fluid management. This led some patients to a cycle of limit testing in which the perceived lack of association between behavior and symptom onset decreased future motivation to follow recommendations. As the cycle progressed, deteriorating function went unperceived until their health status was too poor to manage at home.

Well, if I say boy, I really feel like a piece of cheese and I shouldn’t eat that because it’s very bad, and then I say hell with it and I eat it. Do I feel the effects? No, if I did, I wouldn’t eat it. (male, readmission)

Comorbidities

The presence of comorbid conditions played an important role in the ability of patients to follow recommendations. Patients reported difficulties consolidating the medication and diet instructions recommended by different healthcare providers. For some patients, comorbidities did not interfere with their management of heart failure; however, for others, comorbidities represented an additional obstacle.

Socio-economic Factors

Some patients reported financial difficulties caused by poor health insurance and physical limitations preventing them from working. Those with limited resources often made management decisions based on which medications or foods they could afford.

Hopelessness from Treatment Failure Despite Good Adherence

Patients often reported stress, frustration, hopelessness, and nihilism as a result of a perceived worsening state or lack of progress despite following treatment recommendations. These feelings were expressed regardless of whether or not patients felt comfortable managing heart failure at home. Some patients reported managing these emotions through the use of positive coping skills that did not hinder their heart failure management, such as seeking emotional support from friends and family. However, in other patients, these emotions precluded effective home heart failure management. In some patients, the emotional reactions to home management failure trapped them in a cycle of despair characterized by decreased adherence, worsening symptoms, and intensification of negative emotions.

I like to know how to manage CHF better but I don’t know if there’s a better way of managing it. I don’t know because I’ve tried to take my fluids and not eat salt and all that and I still ended up in the hospital. (female, post-index admission)

Emotional Response to Limitations

All patients reported frustration towards new limitations to their daily activities brought about by heart failure and its management. Some mourned not being able to consume their favorite foods and the burden of new physical limitations. Others reported resentment towards work restrictions and dependence on others to perform activities of daily living, at times reporting feelings of jealousy towards friends who were not limited by disease. Patients reported isolation caused by difficulties leaving their homes due to decreased physical capacity and constant urination related to use of diuretics. The emotions brought about by heart failure were so overwhelming at times that patients resorted to mitigating these negative feelings by adapting their home management strategies.

Well, they say don’t eat hot dogs, then I eat hot dogs. And they tell you to stay away from lunchmeats. Well, sometimes the lunchmeat is expensive, sometimes they’re not. But when it’s on sale, I like baloney and I like liverwurst and onion sandwich on rye. But there’s things that I like that I just go get it, because I look at it, you’re only going to live once and you might as well enjoy yourself, because if you don’t, you’re going to die and never enjoy yourself. I just figure I enjoy myself and I don’t have no problems with them. (male, post-index admission)

Readmission as a Rational Choice

Readmission was often a joint decision between patients and their families. The main reason cited for readmission was the fear brought about by difficulty distinguishing symptoms that were truly life-threatening from those that could be safely managed at home. Despite feelings of ambivalence, the hospital was ultimately viewed by patients (and endorsed by their caregivers) as the safest place for recovery. Overall, patients did not view readmission as a “negative” outcome.

Shortness of Breath and Emotional Response

Patients reported intense emotional responses to the onset of shortness of breath including fear, stress, anxiety, and depression. In some, the emotional response further exacerbated symptoms. While some patients reported consulting a health care professional following the onset of symptoms, others reported symptoms being so distressing that a return to the hospital was seen as the safest decision. Patients reported difficulties interpreting how the quality of their symptoms correlated with medical severity. Some felt stress from being unable to judge whether the slightest overexertion would trigger distressing symptoms. Others felt fear from a lack of obvious heart failure symptoms and thus an inability to know if they were overexerting themselves. This uncertainty made it challenging for patients to determine when hospitalization was necessary.

I can’t go to the hospital every time I got a pain, because I don’t know if it’s the heart or – usually when the heart acts up I can’t breathe right. Course, pneumonia does the same thing, so – you know. (male, readmission)

Ambivalence Towards Hospitalization

Patients reported a range of feelings towards the hospital. Some reported strongly disliking being in the hospital because they felt boredom, thought it was a waste of time, and did not like being confined to bed. One patient compared being in the hospital to being incarcerated, while another said it made them feel like a vegetable. Despite these negative feelings, patients and caregivers felt that the hospital was the safest place to recover and regain control of their disease.

How do I feel about being in the hospital? Is that a trick question? I mean, I like my bed at home. It’s okay. It’s okay. That’s all. I mean, I feel safer there when I’m not feeling well. Of course, I feel safer there where they can monitor me, but otherwise I’d rather be home. (male, post-index admission)

At times, patients were willing and in agreement to go to the hospital and at other times they resisted for a number of reasons, including not wanting to go to the hospital or missing out on life events. They reported that their caregivers supported the decision to return to the hospital because of fear of negative outcomes “on their watch.” No patient reported viewing rehospitalization as a “negative” outcome.

DISCUSSION

Through this qualitative study, we found that adherence to medical recommendations is not viewed by patients as a binary behavior (i.e., good vs. poor adherence), but as a part of a spectrum in which recommendations are adapted to conform with individual circumstances. The association that patients perceive between their behaviors and symptom onset and severity is an important driver of patient adaptation of medical recommendations. Ultimately, patients viewed hospital admissions as a rational choice rather than as a negative outcome. Based on these findings, we have developed a conceptual framework (Fig. 1) to understand patients’ perspectives regarding challenges to home heart failure management and reasons for readmission.

We identified two cycles that play an important role in home management behaviors of patients: a cycle of limit testing and a cycle of despair (Fig. 1). The cycle of limit testing occurred in patients who felt uncertainty regarding the recommendations that they had received, and experienced temporal incongruence between poor adherence and symptom onset. This prompted decreasing adherence, leading to worsening function, which at times, went unperceived until it was too severe to safely manage at home and resulted in readmission. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which have found inadequate instructions and insufficient knowledge to be important challenges to home heart failure management.10,11,12 Our findings provide further insight into the important role that a patient’s experience of symptoms can play in adherence. In addition, the changing nature of adherence and adaptation, as described in our study, may help explain the limited effectiveness of brief interventions that focus on anticipatory guidance and supports the use of comprehensive longitudinal interventions.6

The cycle of despair occurred in patients who experienced worsening symptoms and functional status despite perceived good adherence. This inconsistency resulted in profound psychological distress characterized by feelings of hopelessness and frustration. Their distress led to decreased adherence, worsening symptoms, and intensification of negative emotions. This finding is consistent with previous studies, which have described the strong emotions that patients experience in response to the challenges and limitations of having heart failure.9,12 Our study provides further evidence of the strong effect that emotional factors can have on adherence. This finding helps explain why interventions must address not only the logistical and physical challenges patients face, but also their psychological needs.

As both cycles progressed, patients experienced increasingly distressing symptoms and fear. This prompted many patients and caregivers to decide to return to the hospital without consulting a healthcare provider. This is consistent with previous studies, which have found worsening symptoms to be one of the most commonly cited reason for readmission by patients.9,12,13 Our study further shows that, while patients feel ambivalence towards the hospital, they view readmission as the safest and most rational choice rather than as a “negative” outcome. This novel finding supports the unique contribution that qualitative methods play in identifying patient-centered outcomes and using these to inform tailored interventions.14 In addition, this finding has significant public policy implications as the current assumption is that rehospitalization is a “systems failure” and that clinicians and hospitals should be penalized financially when it occurs. The fact that patients, in some circumstances, prefer hospitalization, challenges this assumption and suggests value in interventions and policies that focus on outcomes other than rehospitalization as a measurement of health system performance. Further, our findings suggest that “adaptation” may be a more patient-centered descriptor and target of interventions than “non-adherence.”

Our study was subject to some limitations. As with all qualitative research, our results do not make causal inferences, but are useful for hypothesis generation. The generalizability of our study is also limited. Nonetheless, having conducted our interviews in a relatively large sample of a diverse group of patients at different stages of disease and vetting our conclusions with focus groups, we believe we have arrived at internally valid results that will be a useful guide for future studies. Because our study was not designed to formally compare differences among participants with a readmission vs an index admission, we cannot determine if these groups have meaningful differences in their experiences. However, we did not identify any qualitative differences in their responses.

The conceptual framework developed in this study indicates that interventions based solely on symptom and fluid management, adherence, or knowledge may be suboptimal because they do not fully align with the needs and goals of patients, caregivers, and providers. Our findings suggest that providing care that comprises pain and symptom management, psychological, spiritual, and social support, assistance with treatment decision-making, and complex care coordination—tenets of palliative care—might optimize heart failure management. These palliative care approaches can be beneficial if applied earlier (i.e., not just at end of life) and more broadly to heart failure patients.3,15,16 Although current heart failure clinical guidelines recommend the use of palliative care,17,18 there is limited training and resources available for implementation and it is not yet standard of care. Given the millions of patients who may benefit from such care, more research is needed to determine the optimal integration of palliative care into heart failure management, particularly with regard to timing and method of administration.

References

Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2017 update: A report from the american heart association. Circulation. 2017;135(10):e146–603.

Bekelman DB, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, et al. Symptom burden, depression, and spiritual well-being: A comparison of heart failure and advanced cancer patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(5):592–8.

McIlvennan CK, Allen LA. Palliative care in patients with heart failure. BMJ (Online). 2016;353.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; hospital inpatient prospective payment systems for acute care hospitals and the long-term care hospital prospective payment system and FY 2012 rates; hospitals’ FTE resident caps for graduate medical education payment. Final rules. Fed Regist. 2011 Aug 18;76(160):51476–846.

Fleming LM, Kociol RD. Interventions for heart failure readmissions: Successes and failures. Curr Heart Fail Rep. 2014;11(2):178–87.

Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–8.

Soundarraj D, Singh V, Satija V, Thakur RK. Containing the Cost of Heart Failure Management: A Focus on Reducing Readmissions. Heart Fail Clin. 2017 Jan; 13(1):21–8.

Ahmad FS, Barg FK, Bowles KH, et al. Comparing Perspectives of Patients, Caregivers, and Clinicians on Heart Failure Management. J Card Fail. 2016;22(3):210–7.

Annema C, Luttik ML, Jaarsma T. Reasons for readmission in heart failure: Perspectives of patients, caregivers, cardiologists, and heart failure nurses. Heart Lung. 2009 Sep-Oct;38(5):427–34.

Clark AM, Spaling M, Harkness K, et al. Determinants of effective heart failure self-care: a systematic review of patients’ and caregivers’ perceptions. Heart. 2014 May; 100(9):716–21.

Currie K, Strachan PH, Spaling M, Harkness K, Barber D, Clark AM. The importance of interactions between patients and healthcare professionals for heart failure self-care: A systematic review of qualitative research into patient perspectives. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2015 Dec; 14(6):525–35.

Jeon YH, Kraus SG, Jowsey T, Glasgow NJ. The experience of living with chronic heart failure: a narrative review of qualitative studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010 Mar 24;10:77,6963–10–77.

Retrum JH, Boggs J, Hersh A, et al. Patient-identified factors related to heart failure readmissions. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013 Mar 1;6(2):171-

Curry LA, Nembhard IM, Bradley EH. Qualitative and mixed methods provide unique contributions to outcomes research. Circulation. 2009;119(10):1442–52.

Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, et al. Palliative care in heart failure: The PAL-HF randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(3):331–41.

Diop MS, Rudolph JL, Zimmerman KM, Richter MA, Skarf LM. Palliative Care Interventions for Patients with Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Palliative Med. 2017;20(1):84–92.

McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2012 Jul;33(14):1787–847.

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Oct 15;62(16):e147–239.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of Elizabeth Stelson, MSW; Breah Paciotti, MPH; and their colleagues in the Mixed Methods Research Lab (MMRL). Ms. Stelson and Ms. Paciotti conducted and coded the qualitative interviews with assistance from the MMRL staff.

The team would like to dedicate this article to Thomas Gallagher, our patient partner, who changed the way we understand the experience of people with heart failure. Tom passed away as this article was being prepared, but his voice will live on through these words.

Contributors

All those who contributed to the manuscript meet criteria for authorship.

Prior Presentations

This work was presented as a poster on April 3rd, 2017, at the 2017 American Heart Association Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Scientific Sessions in Arlington, VA.

Funding

This work has received funding from the following sources:

•PCORI grant 1IP2PI000186-02 to SEK and FKB

•American Heart Association 2016 Student Scholarship in Cardiovascular Disease to JSC.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors would like to disclose the following potential conflicts of interests:

Jonathan Sevilla-Cazes, MD, MPH: None

Kathryn H Bowles, PhD, RN, FAAN, FACMI: None

Faraz S. Ahmad, MD: None

Tom Gallagher: None

Shreya Kangovi, MD, MSHP: None

Lee R Goldberg, MD, MPH: Medtronic

Lynn Alexander: None

Anne Jaskowiak, MS, BSW: None

Barbara Riegel, PhD, RN, FAAN, FAHA: None

Frances K Barg, PhD, MEd: None

Stephen E Kimmel, MD, MSCE: Bayer, Pfizer.

Additional information

Tom Gallagher was a patient representative and died before publication of this work was completed.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 50 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sevilla-Cazes, J., Ahmad, F.S., Bowles, K.H. et al. Heart Failure Home Management Challenges and Reasons for Readmission: a Qualitative Study to Understand the Patient’s Perspective. J GEN INTERN MED 33, 1700–1707 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4542-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4542-3