Abstract

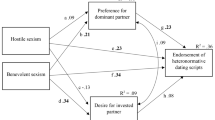

Gender-based structural power and heterosexual dependency produce ambivalent gender ideologies, with hostility and benevolence separately shaping close-relationship ideals. The relative importance of romanticized benevolent versus more overtly power-based hostile sexism, however, may be culturally dependent. Testing this, northeast US (N = 311) and central Chinese (N = 290) undergraduates rated prescriptions and proscriptions (ideals) for partners and completed Ambivalent Sexism and Ambivalence toward Men Inventories (ideologies). Multiple regressions analyses conducted on group-specific relationship ideals revealed that benevolent ideologies predicted partner ideals, in both countries, especially for US culture’s romance-oriented relationships. Hostile attitudes predicted men’s ideals, both American and Chinese, suggesting both societies’ dominant-partner advantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 111–125.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 633–642.

Begany, J. J., & Milburn, M. (2002). Psychological predictors of sexual harassment: Authoritarianism, hostile sexism, and rape myths. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 3, 119–126.

Berscheid, E., & Meyers, S. A. (1996). A social categorical approach to a question about love. Personal Relationships, 3, 19–43.

Brehm, S. S. (1992). Intimate relationships. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Burgess, D., & Borgida, E. (1999). Who women are, who women should be: Descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotyping in sex discrimination. Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law, 5, 665–692.

Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Attractive women want it all: Good genes, economic investment, parenting proclivities, and emotional commitment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 134–146.

Chen, Z., Fiske, S. T., & Lee, T. L. (2009). Ambivalent sexism and power-related gender-role ideology in marriage. Sex Roles, 60, 765–778.

Christopher, A. N., & Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 223–230.

Dion, K. K., & Dion, K. L. (1993). Individualistic and collectivistic perspectives on gender and the cultural context of love and intimacy. Journal of Social Issues, 49, 53–69.

Dion, K. K., & Dion, K. L. (1996). Cultural perspectives on romantic love. Personal Relationships, 3, 5–17.

Eastwick, P. W., Eagly, A. H., Glick, P., Johannesen-Schmidt, M., Fiske, S. T., Blum, A., et al. (2006). Is traditional gender ideology associated with sex-typed mate preferences? A test in nine nations. Sex Roles, 54, 603–614.

Feather, N. T. (2004). Value correlates of ambivalent attitudes toward gender relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 3–12.

Glick, P., Diebold, J., Bailey-Werner, B., & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1323–1334.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119–135.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The ambivalence toward men inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 519–536.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 115–188). Thousand Oaks: Academic.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., et al. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728.

Glick, P., Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., Ferreira, M. C., & de Souza, M. A. (2002). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward wife abuse in Turkey and Brazil. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 292–297.

Goodenough, W. H. (1970). Describing a culture. Description and comparison in cultural anthropology (pp. 104–119). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, S. A., Fiske, S. T., Rosen, L. D., & Rosenthal, A. M. (2002). The eye of the beholder: Romantic goals and impression biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 232–241.

Hsu, F. L. K. (1981). Americans and Chinese: Passage to differences (3rd ed.). Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii.

Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & Eagly, A. H. (2002). Another look at sex differences in preferred mate characteristics: The effects of endorsing the traditional female gender role. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 322–328.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509.

King, M. P., (Writer) & Van Patten, T. (Director). (2004). An American girl in Paris (part deux). In J. Rottenberg & E. Zuritsky (Producers), Sex and the city. New York: HBO.

Kephart, W. M. (1967). Some correlates of romantic love. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 29, 470–474.

Kurzban, R., & Weeden, J. (2005). Hurrydate: Mate preferences in action. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 227–244.

Levine, R., Sato, S., Hashimoto, T., & Verma, J. (1995). Love and marriage in eleven cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26, 554–571.

Masser, B. M., & Abrams, D. (1999). Contemporary sexism: The relationships among hostility, benevolence, and neosexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 503–517.

Masser, B. M., & Abrams, D. (2004). Reinforcing the glass ceiling: The consequences of hostile sexism for female managerial candidates. Sex Roles, 51, 609–615.

Pimentel, E. E. (2000). Just how do I love thee?: Marital relations in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 32–47.

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 269–281.

Riley, N. E. (1994). Interwoven lives: Parents, marriage, and Guanxi in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 791–803.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 743–762.

Rudman, L. A., & Heppen, J. B. (2003). Implicit romantic fantasies and women’s interest in personal power: A glass slipper effect? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1357–1370.

Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., & Glick, P. (2003). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward women who engage in premarital sex in Turkey. The Journal of Sex Research, 40, 296–302.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology Vol. 25 (pp. 1–65). Orlando: Academic.

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696.

Simpson, J., Campbell, B., & Berscheid, E. (1986). The association between romantic love and marriage: Kephart (1967) twice revisited. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, 363–372.

Sprecher, S., Aron, A., Hatfield, E., Cortese, A., Potapova, E., & Levitskaya, A. (1994). Love: American style, Russian style, and Japanese style. Personal Relationships, 1, 349–369.

Stafford, L., & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8, 217–242.

Tiedens, L. Z. (2001). Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: The effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 86–94.

United Nations Development Programme. (2005). Human development report 2005. New York: Oxford University Press.

Viki, G. T., & Abrams, D. (2002). But she was unfaithful: Benevolent sexism and reactions to rape victims who violate traditional gender role expectations. Sex Roles, 47, 289–293.

Viki, G. T., Abrams, D., & Hutchison, P. (2003). The “true” romantic: Benevolent sexism and paternalistic chivalry. Sex Roles, 49, 533–537.

Wang, C. D., & Mallinckrodt, B. S. (2006). Differences between Taiwanese and U.S. cultural beliefs about ideal adult attachment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 192–204.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrew Conway for his helpful advice on statistical analyses and Blair Moorhead for her help in coding data. We are also grateful to James Chu of Princeton University’s Office of Information Technology for his assistance in collecting open-ended data. This research was supported partially by a grant from Chinese National Social Science Foundation (09BSH045) and Culture and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (08JA630027) for the fourth author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix A

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory

Chinese version:

-

1.

很多女人拥有男人缺乏的纯洁品质。(B)

-

2.

女人应该受到男人的宠爱和保护。(B)

-

3.

女人试图通过控制男人来获得权力。(H)

-

4.

每个男人都应该有一个他爱慕的女人。(B)

-

5.

没有女人的男人不完整。(B)

-

6.

女人往往夸大她们在工作中的问题。(H)

-

7.

女人一旦得到男人对她的承诺, 就希望把他成天圈住。(H)

-

8.

当女人在与男人的公平竞争中失利时, 她们总抱怨自己受到了性别歧视。(H)

-

9.

许多女人喜欢戏弄男人, 她们让男人觉得似乎可以得到她, 然后又拒绝他。(H)

-

10.

女人比男人往往有更高的道德感。(B)

-

11.

男人应该甘愿牺牲自己为女人提供经济保证。(B)

-

12.

女权主义者正向男人提出无理要求。(H)

English version:

-

1.

Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess. (B)

-

2.

Women should be cherished and protected by men. (B)

-

3.

Women seek to gain power by getting control over men. (H)

-

4.

Every man ought to have a woman whom he adores. (B)

-

5.

Men are incomplete without women. (B)

-

6.

Women exaggerate problems they have at work. (H)

-

7.

Once a woman gets a man to commit to her, she usually tries to put him on a tight leash. (H)

-

8.

When women lose to men in a fair competition, they typically complain about being discriminated against. (H)

-

9.

Many women get a kick out of teasing men by seeming sexually available and then refusing male advances. (H)

-

10.

Women, compared to men, tend to have a superior moral sensibility. (B)

-

11.

Men should be willing to sacrifice their own well being in order to provide financially for the women in their lives. (B)

-

12.

Feminists are making unreasonable demands of men. (H)

Note. All items used a 6-point scale (0 = Disagree strongly; 5 = Agree strongly). Items denoted with (B) express benevolent attitudes; items denoted with (H) express hostile attitudes.

Appendix B

Ambivalence toward Men Inventory

Chinese version:

-

1.

即便夫妇双方都有工作, 在家里妻子也应多照顾丈夫。(H)

-

2.

男人“帮助”女人往往是为了显示他们比女人强。(H)

-

3.

每个女人都需要一个珍爱自己的男人。(B)

-

4.

如果没有一段忠诚、长期的爱情, 女人的一生就不完整。(B)

-

5.

男人生病时简直像个孩子。(H)

-

6.

男人总是争取比女人在社会上拥有更多权力。(H)

-

7.

男人可以为女人提供经济保障。(B)

-

8.

即便是那些声称自己尊重女性权利的男人, 他们其实也想要一个妻子在家里履行绝大部分家务、照顾孩子的传统夫妻关系。(H)

-

9.

男人更愿意冒着危险去帮助他人。(B)

-

10.

一旦失去身份地位, 很多男人真像孩子。(H)

-

11.

男人比女人更喜欢冒险。(B)

-

12.

一旦拥有权力和机会, 很多男人都会对女人进行性骚扰, 即使仅仅是微妙的骚扰。(H)

English version:

-

1.

Even if both members of a couple work, the woman ought to be more attentive to taking care of her man at home. (B)

-

2.

When men act to “help” women, they are often trying to prove they are better than women. (H)

-

3.

Every woman needs a male partner who will cherish her. (B)

-

4.

A woman will never be truly fulfilled in life if she doesn’t have a committed, long-term relationship with a man. (B)

-

5.

Men act like babies when they are sick. (H)

-

6.

Men will always fight to have greater control in society than women. (H)

-

7.

Men are mainly useful to provide financial security for women. (B)

-

8.

Even men who claim to be sensitive to women’s rights really want a traditional relationship at home, with the woman performing most of the housekeeping and child care. (H)

-

9.

Men are more willing to put themselves in danger to protect others. (B)

-

10.

When it comes down to it, most men are really like children. (H)

-

11.

Men are more willing to take risks than women. (B)

-

12.

Most men sexually harass women, even if only in subtle ways, once they are in a position of power over them. (H)

Note. All items used a 6-point scale (0 = Disagree strongly; 5 = Agree strongly). Items denoted with (B) express benevolent attitudes; items denoted with (H) express hostile attitudes.

Appendix C

American Men’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix D

American Men’s Proscriptive Ideals

Appendix E

American Women’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix F

American Women’s Proscriptive Ideals

Appendix G

Chinese Men’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix H

Chinese Men’s Proscriptive Ideals

Appendix I

Chinese Women’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix J

Chinese Women’s Proscriptive Ideals

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, T.L., Fiske, S.T., Glick, P. et al. Ambivalent Sexism in Close Relationships: (Hostile) Power and (Benevolent) Romance Shape Relationship Ideals. Sex Roles 62, 583–601 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x