Abstract

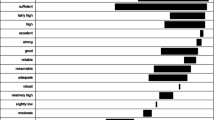

Using a field experiment with high school students, we evaluate the development of risk preferences. Examining the impact of school characteristics on preference development reveals both peer and quality effects. For the peer effect, individuals in schools with a higher percentage of students on free or reduced lunches (hence a higher proportion of low-income peers with whom to interact) are significantly more risk averse. For the quality effect, individuals in schools with smaller class sizes and a higher percentage of educators with advanced degrees have higher, more moderate levels of risk aversion. We further discuss economic, cognitive and emotional development theories of risk preferences. Data show demographic-related patterns: girls are more risk averse on average, while taller and nonwhite individuals are more risk tolerant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Further, children’s preferences often conform to standard theoretical predictions. For example, children’s decisions have been shown to conform to GARP as competently as adults by sixth grade (Harbaugh et al. 2001a), and to vary in expected or reasonable manners with changes in choice parameters (Eckel et al. 2010; Harbaugh et al. 2001b). Other studies examining the preferences of children have focused on the role of socio-economic or demographic differences between children (e.g., for time preference, see Castillo et al. 2008; for competition see Houser and Schunk 2009; Bartling et al. 2012).

Considerable prior research examines the relationship between ethnicity and risk-taking for teens. Whites are more likely to engage in some risky behaviors, like smoking, while nonwhites are more likely to engage in others, like sexual intercourse or violence (Blum et al. 2000; Gruber 2001). There does not appear to be a stable pattern of differences in risk-taking across ethnic groups, but rather such differences vary by domain.

Note that evidence suggests that adolescents and adults are able to similarly evaluate risks (Steinberg 2007 and references therein).

Additionally, Problem Behavior Theory (PBT) integrates ideas from each, but is mainly a social development theory focusing on the influence of family structure and home environment (e.g., Jessor 1991). Our study collects data at the individual level, not at the family level, so we are unable to evaluate PBT in this setting.

We are unable to examine psychobiological theories due to data limitations.

The Adult Literacy and Life Skills Survey (ALL) is a large-scale co-operative effort undertaken by governments, national statistics agencies, research institutions and multi-lateral agencies designed to enable an international comparison of skills. The development and management of the study were coordinated by Statistics Canada and the Educational Testing Service (ETS) in collaboration with the other US and international statistical agencies. The ALL study builds on the International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS). The foundation skills measured in the ALL survey include prose literacy, document literacy, numeracy, and problem solving. In this study we used the numeracy measure, which consists of 40 problems developed to assess the ability to use mathematics in everyday life. The test was provided and scored by Statistics Canada. For more detail see Statistics Canada and OECD (2005).

Several recent studies show a marked correlation between measures of cognitive ability (mathematical literacy or IQ) and risk and time preferences. Dohmen et al. (2010) address this relationship in a representative sample of one thousand German adults, and find that lower cognitive ability is associated with greater risk aversion. Burks et al. (2009) find a similar result for a sample of workers in a trucking firm.

Similar procedures were followed in St. Cloud. The implementation differed slightly in that sessions were run over the period of only one week and gift cards were for local businesses.

In some sessions the order of the dictator and ultimatum tasks was reversed.

This risk-preference measure has been used in a number of studies with average CRRA estimates that are between 0.4–0.7. Estimates appear high here, but keep in mind that is assuming the CRRA functional form is correct. Our approach in this study is to classify subjects as relatively more or less risk averse.

University students were recruited from large principles of economics classes at Virginia Tech. Six sessions were conducted in April and May of 2005 at the Lab for the Study of Human Thought and Action. The protocol was identical to that used in the high schools, including the stakes. The number of subjects was 91.

An alternative approach would be to assume a specific functional form for the utility function of participants (such as CRRA) and estimate the relationship conditional on this assumption. Since we do not have data sufficient to test the CRRA assumption, we have presented the results in a less-structured, more general form.

We also test for the impact of the school’s ethnic heterogeneity and being a member of the ethnic majority of the school, neither of which were found to be significant in any specification.

A school’s student-teacher ratio might be related to the household income and wealth of families who are sending their children to the school. A similar argument can be made for the percentage of instructors holding advanced degrees, as the higher level of resources available to schools in wealthier areas would allow them to recruit more educated teachers. However, since many of these decisions are made at the district level, and we only include schools from two districts, we do not believe these variables accurately represent economic disadvantage in our sample. Class size is controlled by the district, since it sets catchment areas for each school and school classroom capacity. Teacher qualifications are likely driven by district-wide rewards for higher degrees and, within a district, a teacher’s ability to move between schools is limited by district policies.

Note that we use the term peer effect to indicate the social and economic environment of the students’ peers at the school, rather than as the influences from students’ friends.

For a subset of the population we also have census data for their zip code. The impact of low-income peers is not affected by including census data as a control for that subset of the sample.

With one exception: the percent of families (but not individuals) in poverty is positive and statistically significant (but economically small, coef. = 0.0002). Including this variable does not alter any of the other results.

The results are not sensitive to specification as an ordered logit or to OLS, using gamble number (which would impose an underlying linear structure) or CRRA (from Table 1 above).

This elicitation is similar to “multiple price list” elicitation methods such as that developed by Coller and Williams (1999). Alternatively, these choices can be used to estimate an individual discount rate. The results are not sensitive to alternative specifications of this variable. We use this measure for simplicity.

References

Afridi, F., Li, S. X., & Ren, Y. (2011). Social identity and inequality: The impact of China’s Hukou system. Working paper.

Almås, I., Cappelen, A. W., Sørensen, E., & Tungodden, B. (2010). Fairness and the development of inequality acceptance. Science, 328(5982), 1176–1178.

Anderson, L. R., & Mellor, J. M. (2008). Predicting health behaviors with an experimental measure of risk preference. Journal of Health Economics, 27, 1260–1274.

Ball, S. B., Eckel, C. C., & Heracleous, M. (2010). Risk preferences and physical prowess: prediction choice and bias. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 41(3), 167–193.

Barsky, R. B., Juster, F. T., Kimball, M. S., & Shapiro, M. D. (1997). Preference parameters and behavioral heterogeneity: an experimental approach in the Health and Retirement Study. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(2), 537–579.

Bartling, B., Fehr, E., & Schunk, D. (2012). Health effects on children’s willingness to compete. Experimental Economics, 15(1), 58–70.

Becker, G. M., DeGroot, M. H., & Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behavioral Science, 9(3), 226–232.

Binswanger, H. (1980). Attitudes toward risk: experimental measurement in rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62, 395–407.

Binswanger, H. (1981). Attitudes toward risk: theoretical implications of an experiment in rural India. The Economic Journal, 91, 867–890.

Blum, R. W., Beuhring, T., Shew, M. L., Bearinger, L. H., Sieving, R. E., & Resnick, M. D. (2000). The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behavior. American Journal of Public Health, 90(12), 1879–1884.

Bonin, H., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2007). Cross-sectional earnings risk and occupational sorting: the role of risk attitudes. Labour Economics, 14, 926–937.

Boyer, T. W. (2006). The development of risk-taking: a multi-perspective review. Developmental Review, 26, 291–345.

Bucciol, A., Houser, D., & Piovesan, M. (2010). Willpower in children and adults: a survey of results and economic implications. International Review of Economics, 57(3), 259–267.

Burks, S., Carpenter, J., Goette, L., & Rustichini, A. (2009). Cognitive skills explain economic preferences, strategic behavior and job attachment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 106, 7745–7750.

Castillo, M., Ferraro, P., Jordan, J., & Petrie, R. (2008). The today and tomorrow of kids. Working paper.

Coller, M., & Williams, M. B. (1999). Eliciting individual discount rates. Experimental Economics, 2, 107–127.

Croson, R. T. A., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474.

Dave, C., Eckel, C. C., Johnson, C. A., & Rojas, C. (2010). Eliciting risk preferences: when is simple better? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 41(3), 219–243.

Deck, C., Lee, J., Reyes, J., & Rosen, C. (2012). Measuring risk aversion on multiple tasks: Can domain specific risk attitudes explain apparently inconsistent behavior? Unpublished manuscript, University of Arkansas.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2009). Individual risk attitudes: measurement, determinants and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? American Economic Review, 100, 1238–1260.

Donohew, L., Zimmerman, R., Cupp, P. S., Novak, S., Colon, S., & Abell, R. (2000). Sensation seeking, impulsive decision-making, and risky sex: implications for risk-taking and design of interventions. Personality and Individual Differences, 28, 1079–1091.

Eckel, C. C., & Grossman, P. J. (2008). Forecasting risk attitudes: an experimental study using actual and forecast gamble choices. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 68(1), 1–17.

Eckel, C., Johnson, C. A., & Montmarquette, C. (2005). Saving decisions of the working poor: Short- and long-term horizons. In J. Carpenter, G. W. Harrison, & J. A. List (Eds.), Research in experimental economics, Volume 10: Field experiments in economics (pp. 219–260). Greenwich: JAI Press.

Eckel, C., Grossman, P. J., Johnson, C. A., de Oliveira, A. C. M., Rojas, C., & Wilson, R. (2010). (Im)patience among adolescents: A methodological note. Working paper.

Eckel, C., Grossman, P. J., Johnson, C. A., de Oliveira, A. C. M., Rojas, C., & Wilson, R. (2011). Social norms of sharing in high school: teen giving in the dictator game. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 80(3), 603–612.

Fehr, E., Rützler, D., & Sutter, M. (2011). The development of altruism, spite and parochialism in childhood and adolescence. IZA Discussion Paper No. 5530.

Fischhoff, B., Parker, A. M., Bruine de Bruin, W., Downs, J., Palmgren, C., Dawes, R., & Manski, C. F. (2000). Teen expectations for significant life events. Public Opinion Quarterly, 64(2), 189–205.

Gollier, C., & Pratt, J. W. (1996). Risk vulnerability and the tempering effect of background risk. Econometrica, 65(4), 1109–1123.

Grossman, P. J., & Lugovskyy, O. (2011). An experimental test of the strength of gender stereotypes. Economic Inquiry, 49, 598–611.

Gruber, J. (Ed.) (2001). Risky Behavior Among Youths: An Economic Analysis. NBER Conference Report. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Guiso, L., & Paiella, M. (2008). Risk aversion, wealth, and background risk. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(6), 1109–1150.

Häger, K., Oud, B., & Schunk, D. (2011). Egalitarian envy: Cross-cultural variation in the development of envy in children. Working paper.

Harbaugh, W. T., & Krause, K. (2000). Children’s altruism in public good and dictator experiments. Economic Inquiry, 38(1), 95–109.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Berry, T. R. (2001). GARP for kids: on the development of rational choice behavior. American Economic Review, 91(5), 1539–1545.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Are adults better behaved than children? Age, experience, and the endowment effect. Economics Letters, 70(2), 175–181.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2002). Risk attitudes of children and adults: choices over small and large probability gains and losses. Experimental Economics, 5, 53–84.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., Liday Jr., S. G., & Vesterlund, L. (2003). Trust in children. In E. Ostrom & J. Walker (Eds.), Trust and reciprocity: Interdisciplinary lessons from experimental research. New York: Russell Sage.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2007). Learning to bargain. Journal of Economic Psychology, 28, 127–142.

Hill, E. M., Ross, L. T., & Low, B. S. (1997). The role of future unpredictability in human risk-taking. Human Nature, 8(4), 287–325.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. American Economic Review, 92, 1644–1655.

Houser, D., & Schunk, D. (2009). Social environments with competitive pressure: gender effects in the decisions of German schoolchildren. Journal of Economic Psychology, 30(4), 634–641.

Jessor, R. (1991). Risk behavior in adolescence: a psychosocial framework for understanding and action. Journal of Adolescent Health, 12, 597–605.

Jones, J. M. (1994). An exploration of temporality in human behavior. In: R. C. Schank & L. Ellen (Eds.), Beliefs, reasoning and decision making: Psycho-logic in honor of Bob Abelson (pp. 389–411). Lawrence Earlbaum Associates, Inc.

Kaplow, L. (2005). The value of a statistical life and the coefficient of relative risk aversion. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 31(1), 23–34.

Lee, J. (2008). The effect of the background risk in a simple chance improving decision model. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 36, 19–41.

Levin, I. P., & Hart, S. S. (2003). Risk preferences in young children: early evidence of individual differences in reaction to potential gains and losses. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 16, 397–413.

Levin, I. P., Hart, S. S., Weller, J. A., & Harshman, L. A. (2007). Stability of choices in a risky decision-making task: a 3-year longitudinal study with children and adults. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 20, 241–252.

Li, J. (2011). The demand for a risky asset in the presence of background risk. Journal of Economic Theory, 146, 372–391.

Males, M. (2009). Does the adolescent brain make risk taking inevitable. Journal of Adolescent Research, 24, 3–20.

Martinsson, P., Nordblom, K., Rützler, D., & Sutter, M. (2011). Social preferences during childhood and the role of gender and age – an experiment in Austria and Sweden. Economics Letters, 110, 248–251.

Mendoza, N. A., & Pracejus, J. W. (1997). Buy now, pay later: does a future temporal orientation affect credit overuse? Advances in Consumer Research, 24, 499–503.

Nguyen, Q. (2011). Does nurture matter: theory and experimental investigation on the effect of working environment on risk and time preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 43, 245–270.

O’Donoghue, T., & Rabin, M. (2002). Risky behavior among youths: Some issues from behavioral economics. In: J. Gruber (Ed.), Risky behavior among youths: An economics analysis. NBER Conference Report, 29–67. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Quiggin, J. (2003). Background risk in generalized expected utility theory. Economic Theory, 22, 607–611.

Robbins, R. N., & Bryan, A. (2004). Relationships between future orientation, impulsive sensation seeking, and risk behavior among adjudicated adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 428–445.

Slovic, P. (1966). Risk-taking in children: age and sex differences. Child Development, 37, 169–176.

Stanford, M. S., & Barratt, E. S. (1992). Impulsivity and the multi-impulsive personality disorder. Personality and Individual Differences, 13, 831–834.

Stanford, M. S., Greve, K. W., Boudreaux, J. K., Mathias, C. W., & Brumbelow, J. L. (1996). Impulsiveness and risk-taking behavior: comparison of high-school and college students using the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 21, 1073–1075.

Statistics Canada & OECD. (2005). Learning a living: First results of the Adult Literacy and Life Skills survey. http://www.statcan.ca/english/freepub/89-603-XIE/2005001/pdf.htm

Sutter, M., & Kocher, M. G. (2007). Trust and trustworthiness across different age groups. Games and Economic Behavior, 59, 364–382.

Sutter, M., & Rützler, D. (2010). Gender differences in competition emerge early in life. Working Papers 2010–14, Faculty of Economics and Statistics, University of Innsbruck.

Sutter, M., Kocher, M. G., Rützler, D., & Trautmann, S. T. (2010). Impatience and uncertainty: Experimental decisions predict adolescents’ field behavior. Discussion Papers in Economics 12114, University of Munich, Department of Economics.

Steinberg, L. (2007). Risk taking in adolescence: new perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 55–59.

Weber, E. U., Blais, A. R., & Betz, N. E. (2002). A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 15(4), 263–290.

White, R. T. (2002). Reconceptualizing HIV infection among poor black adolescent females: an urban poverty paradigm. Health Promotion Practice, 3, 302–312.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Herbert Gintis, the Houston Independent School District, and ISD 742, without whom this project would not have been possible. Additionally, we thank the journal’s editor, an anonymous referee, Eugenia Toma, as well as participants in the ESA International Meetings and the Conference on Measuring Preferences in a Social Context at the Center for Behavioral and Experimental Economic Science (CBEES) at the University of Texas at Dallas for their valuable comments. Funding for this project was provided by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, Network on the Nature and Origin of Preferences and Norms. Any errors remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A Instructions (text only)

Task 1

-

For this task you will select from among six different gambles the one gamble you will play. The six different gambles are illustrated below.

-

Each gamble has two possible outcomes, Low or High.

-

For every gamble, each outcome is equally likely, or has a 50% chance of happening.

-

At the end of the study, if this task is randomly selected, you will roll a ten-sided die to determine which outcome will occur.

-

If you roll a 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5, you will receive the Low outcome.

-

If you roll a 6, 7, 8, 9 or 0, you will receive the High outcome.

-

-

You must select one and only one of these gambles. To select a gamble, put a mark (a large X) on the circle for the pair of outcomes that you select. Mark only one.

-

Your earnings for this task will be determined by:

-

which of the six gambles you select; and

-

whether you roll High or roll Low.

-

For example, say you select the $6, $42 gamble and you roll High (a 6, 7, 8, 9 or 0) with the 10-sided die, you will be paid $42. If you roll Low (a 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5), you will be paid $6.

Question:

Pretend you want to select the gamble for $10, $34. Mark your choice with an X on that pair of outcomes.

Note that if you choose the −$2, $54 gamble and you roll Low, $2 will be taken from your $15 participation fee.

Task 1

You must select one and only one of these gambles. To select a gamble, put a mark (X) on the pair of outcomes that you prefer. Mark only one.

Once you have finished with your decision, close your booklet.

If this task is selected as the one determining your actual earnings, we will have you roll a die to determine the outcome.

Appendix B

Table 6.

Appendix C

Table 7.

Appendix D

Table 8.

Appendix E

Table 9.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eckel, C.C., Grossman, P.J., Johnson, C.A. et al. School environment and risk preferences: Experimental evidence. J Risk Uncertain 45, 265–292 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-012-9156-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-012-9156-2