Abstract

A theoretical framework is presented to explain how agents respond to information under uncertainty in contingent valuation surveys. Agents are provided with information signals and referendum prices as part of the elicitation process. Agents use Bayesian updating to revise prior distributions. An information prompt is presented to reduce hypothetical bias. However, we show the interaction between anchoring and the information prompt creates a systematic bias in willingness to pay. We test our hypotheses in an experimental setting where agents are asked to make a hypothetical, voluntary contribution to a public good. Experimental results are consistent with the model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Murphy et al. (2005a) for a review of the hypothetical bias literature in contingent valuation.

We later extend our theory to address the double-bounded dichotomous choice (DBDC) format, where the issue of incentive incompatibility is discussed.

Herriges and Shogren (1996) and McLeod and Bergland (1999) use a Bayesian approach to examine the issues of anchoring bias (where agents are induced by the question format itself to anchor their responses to an opening referendum price) and incentive incompatibility (where agents are induced by the question format to provide untruthful responses) in CV surveys. Unlike their studies, however, we aim to provide a more formal and general theory of the origins of hypothetical bias and the Bayesian updating process during the value elicitation process.

The empirical evidence is mixed on whether cheap talk is, in general, an effective means of eliminating hypothetical bias in CV and field experiments. Cummings and Taylor (1999) find that a long cheap-talk script is effective in eliminating hypothetical bias. List (2001) and Lusk (2003) use a script similar to that of Cummings and Taylor and find that cheap talk only works for inexperienced consumers. Poe et al. (2002) report that a shorter cheap-talk script is ineffective in eliminating hypothetical bias; Loomis, Gonzales-Caban and Gregory (1994) and Neil (1995) find that reminders about budget constraints and substitutes also are ineffective. Aadland and Caplan (2003) find that, although cheap talk is ineffective overall, it successfully reduces hypothetical bias for certain groups of respondents. However in other work, Cummings, Harrison and Taylor (1995b) and Aadland and Caplan (2006) use a shorter script and find that cheap talk may even exacerbate the hypothetical bias. We offer a theory that is independent of script length and has the potential to explain some of the results that script length cannot. We note, however, that it would be fairly straightforward to incorporate a script-length effect into our Bayesian framework whereby long scripts evoke a larger WTP revision than short scripts.

See Hogg and Craig (1978) for a discussion of Bayesian estimation.

Throughout the paper, we refer to τ i as the “announced price”. In the contingent valuation literature, it is common to refer to τ i as the “referendum bid” or “bid”. We avoid using the term bid in this paper so as not to create any confusion associated with its use in other areas of economics such as auction theory. In the experiment described below subjects are presented with “investment” levels in the public good.

In practice, not all cheap-talk scripts directly inform agents of the magnitude of the hypothetical bias. Instead they often report differences in actual and hypothetical participation rates for public programs or goods (e.g., Cummings and Taylor 1999; Lusk 2003), percentage difference in stated and revealed WTP e.g., (e.g., List 2001), or make a general statement that WTP tends to be misstated in hypothetical scenarios (e.g., Carlsson, Frykblom and Lagerkvist 2005; Aadland and Caplan 2006). It would be fairly straightforward to modify our theory so that, rather than being directly informed of μ and knowing it with certainty, the agent received an indirect signal about μ and was required to infer its value.

The weighted-average form of the updating function in Eq. 11 results if g i (s i |δ i ) is a normal distribution and \(\alpha=\sigma_{h}^{2}/(\sigma_{g}^{2}+\sigma_{h}^{2})\), where \(\sigma_{g}^{2}\) is the variance of g i (s i |δ i ) and \(\sigma_{h}^{2}\) is the variance of the prior distribution h i (δ i ). The formal derivation of Eq. 11 is shown in Appendix 1.

See Laibson and Zeckhauser (1998) for a discussion that relates Kahneman and Tversky’s work to the burgeoning field of “behavioral economics”.

Some may argue that agents are unlikely to adjust their WTP perfectly to the signal c i = μ. For simplicity, we assume perfect adjustments; however it is important to recognize that the subsequent results are robust to partial adjustments where 0 < E i (δ i |c i = μ) < μ.

An interesting implication of this result is that samples with a substantial number of nay-sayers (i.e., low WTP individuals (Carson 2000)) will appear to be more often associated with effective cheap-talk scripts.

For further details on public good experiments, see chapter two in the Handbook on Experimental Economics by Ledyard (1995).

Subjects were informed that not everyone in the group was receiving the same price but were not informed of the distribution of prices across players. In standard CV surveys, agents are given a randomized announced price but generally do not inquire about (and thus are not made aware of) the prices other respondents receive. This is because the cooperative nature of the public good game is not made explicit in field surveys, and because respondents complete the survey independently of one another, thus precluding the need to provide additional knowledge to respondents. The provision of this information represents a deviation from CV surveys in practice, but we do not feel that this alters the fundamental behavioral motives associated with hypothetical bias, cheap talk, and anchoring bias in our experiments.

Recall that the cheap-talk meaure Δ i in Eq. 13 varies across all agents. Here, we are interested in specifying an estimable equation with a constant cheap-talk coefficient, Δ, that is similar to that commonly estimated in the literature and that will enable us to highlight the biases associated with failing to recognize the interaction between cheap talk and anchoring. Also, note that although i in Eq. 13 is defined as the difference between expected values (with and without cheap talk) for the same agent, the econometric analysis will contrast the expected WTP of one set of agents that receive cheap talk (treatment group) with a different set of agents that do not receive cheap talk (control group), holding all other observable factors constant.

As pointed out by an anonymous reviewer, responses to open-ended WTP questions are governed by different incentive compatibility properties than responses to referendum questions. As such, one should exercise caution when using open-ended questions to guide responses to referendum questions. The extent to which the initial open-ended question might alter the agent’s response to cheap talk and the subsequent referendum question is an open and interesting research question.

We also estimated WTP controlling for the demographic variables elicited on the last page of the experiment (see Appendix 2). The control variables include age, gender, income, college GPA, college rank and degree of risk aversion. The observed heterogeneity associated with these variables was not capable of explaining the willingness to invest in the public good. Most of the coefficient estimates associated with the demographic variables were statistically insignificant and did not qualitatively change the estimates of the anchoring and cheap-talk parameters.

The early literature on incentive incompatibility in CV studies (Cummings et al. 1995a, 1997) appears to characterize incentive incompatibility more broadly than some of the more recent studies. For example, Cummings et al. (1995a) on page 260 state that incentive compatibility “implies that subjects will answer the CVM’s hypothetical question in the same way as they would answer an identical question asking for a real commitment.” Whitehead (2002) in a more recent study states on page 287 that in DBDC formats “if the follow-up questions are not incentive compatible, stated willingness to pay will be based on true willingness to pay with a shift parameter.”

References

Aadland, David and Arthur J. Caplan. (2003). “Willingness to Pay for Curbside Recycling with Detection and Mitigation of Hypothetical Bias,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85(2), 492–502.

Aadland, David and Arthur J. Caplan. (2006). “Cheap Talk Reconsidered: Evidence from CVM,” Journal of Economics and Behavioral Organization 60(4), 562–578.

Adamowicz, Wiktor, Jordan Louviere, and Michael Williams. (1994). “Combining Revealed and Stated Preference Methods for Valuing Environmental Amenities,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 26, 271–292.

Alberini, Anna, Barbara Kanninen, and Richard T. Carson. (1997). “Modeling Response Incentive Effects in Dichotomous Choice Contingent Valuation Data,” Land Economics 73(3), 309–324.

Anderson, Lisa R. and Charles A. Holt. (1997). “Information Cascades in the Laboratory,” American Economic Review 87(5), 847–862.

Armantier, Olivier. (2006). “Estimates of Own Lethal Risks and Anchoring Effects,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 32(1), 37–56.

Arrow, Kenneth, Robert Solow, Paul R. Portney, Edward E. Leamer, Roy Radner, and Howard Schuman. (1993). “Report of the NOAA Panel on Contingent Valuation,” Federal Register 58(10), 4601–4614.

Bernheim, Douglas. (1994). “A Theory of Conformity,” Journal of Political Economy 102, 841–877.

Brookshire, David S., Mark A. Thayer, William D. Schulze, and Ralph C. D’Arge. (1982). “Valuing Public Goods: A Comparison of Survey and Hedonic Approaches,” American Economic Review 72(1), 165–177.

Brown, Thomas C., Icek Azjen, and Daniel Hrubes. (2003). “Further Tests of Entreaties to Avoid Hypothetical Bias in Referendum Contingent Valuation,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 46, 353–361.

Cameron, Trudy Ann. (2005).“Updating Subjective Risks in the Presence of Conflicting Information: An Application to Climate Change,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 30(1), 63–97.

Cameron, Trudy Ann and Michelle D. James. (1987). “Efficient Estimation Methods for Close-Ended Contingent Valuation Surveys,” Review of Economics and Statistics 69, 269–276.

Carlsson, Fredrik, Peter Frykblom, and Carl Johan Lagerkvist. (2005). “Using Cheap Talk as a Test of Validity in Choice Experiments,” Economics Letters 89, 147–152.

Carson, Richard T. (2000). “Contingent Valuation: A User’s Guide,” Environmental Science and Technology 34(8), 1413–1418.

Carson, Richard T., Theodore Groves, and Mark J. Machina. (1999). “Incentive and Informational Properties of Preference Questions.” Plenary address, European Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, Oslo, Norway.

Chanel, Olivier, Frederic Aprahamian, and Stephane Luchini. (2007). “Modeling Starting Point Bias as Unobserved Heterogeneity in Contingent Valuation Surveys: An Application to Air Pollution,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 89(2), 533–547.

Cherry, Todd L. and John Whitehead. (2007). “The Cheap-Talk Protocol and the Estimation of the Benefits of Wind Power,” Resource and Energy Economics (in press).

Cummings, Ronald G., David S. Brookshire, and William D. Schulze (eds). (1986). Valuing Environmental Goods: A State of the Art Assessment of the Contingent Valuation Method. Totowa, NJ: Rowman and Allanheld.

Cummings, Ronald G., Glenn W. Harrison, and E. Elisabet Rutstrom. (1995a). “Homegrown Values and Hypothetical Surveys: Is the Dichotomous Choice Approach Incentive Compatible?” American Economic Review 85(1), 260–266.

Cummings, Ronald G., Glenn W. Harrison, and Laura O. Taylor. (1995b). “Can the Bias of Contingent Valuation Surveys be Reduced? Evidence from the Laboratory.” Unpublished manuscript, Division of Research, College of Business Administration, University of South Carolina.

Cummings, Ronald G. and Laura O. Taylor. (1999). “Unbiased Value Estimates for Environmental Goods: A Cheap Talk Design for the Contingent Valuation Method,” American Economic Review 89(3), 649–666.

Cummings, Ronald G., Steven Elliot, Glenn W. Harrison, and James Murphy. (1997). “Are Hypothetical Referenda Incentive Compatible?” Journal of Political Economy 105(3), 609–621.

Gibbons, Robert. (1992). Game Theory for Applied Economists. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Green, Donald, Karen E. Jacowitz, Daniel Kahneman, and Daniel McFadden. (1998). “Referendum Contingent Valuation, Anchoring, and Willingness to Pay for Public Goods,” Resource and Energy Economics 20(2), 85–116.

Hausman, Jerry A. (1993). Contingent Valuation: A Critical Assessment. North Holland, Amsterdam.

Herriges, Joseph A. and Jason F. Shogren. (1996). “Starting Point Bias in Dichotomous Choice Valuation with Follow-Up Questioning,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 30, 112–131.

Hogg, Robert V. and Allen T. Craig. (1978). Introduction to Mathematical Statistics. New York: MacMillan.

Hurd, Michael D. (1999). “Anchoring and Acquiescence Bias in Measuring Assets in Household Surveys,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 19(1), 111–136.

Johannesson, Magnus, Glenn C. Blomquist, Karen Blumenschein, Per-Olov Johansson, Bengt Liljas, and Richard M. O’Conor. (1999). “Calibrating Hypothetical Willingness to Pay Responses,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 8, 21–32.

Kahneman, Daniel and Jack L. Knetsch. (1992). “Valuing Public Goods: The Purchase of Moral Satisfaction,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 22, 57–70.

Laibson, David and Richard Zeckhauser. (1998). “Amos Tversky and the Ascent of Behavioral Economics,” Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 16, 7–47.

Ledyard, John O. (1995). “Public Goods: A Survey of Experimental Research.” In John H. Kagel and Alvin E. Roth (eds), The Handbook of Experimental Economics, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

List, John A. (2001). “Do Explicit Warnings Eliminate the Hypothetical Bias in Elicitation Procedures? Evidence from Field Auction Experiments,” American Economic Review 91(5), 1498–1507.

Loomis, John B., Armando Gonzalez-Caban, and Robin Gregory. (1994). “Do Reminders of Substitutes and Budget Constraints Influence Contingent Valuation Estimates?” Land Economics 70(4), 499–506.

Lusk, Jayson L. (2003). “Effects of Cheap Talk on Consumer Willingness-to-Pay for Golden Rice,” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 85(4), 840–856.

McFadden, Daniel. (2001). “Economic Choices,” American Economic Review 91(3), 351–378.

McLeod, Donald M. and Olvar Bergland. (1999). “Willingness-to-Pay Estimates Using Double-Bounded Dichotomous-Choice Contingent Valuation Format: A Test for Validity and Precision in a Bayesian Framework,” Land Economics 75(1), 115–125.

Mitchell, Robert C. and Richard T. Carson. (1989). “Using Surveys to Value Public Goods: The Contingent Valuation Method.” Unpublished manuscript, Resources for the Future, Washington, DC.

Murphy, James J., P. Geoffrey Allen, Thomas Stevens, and Darryl Weatherhead. (2005a). “A Meta-Analysis of Hypothetical Bias in Stated Preference Valuation,” Environmental and Resource Economics 30(3), 313–325.

Murphy, James J., Thomas Stevens, and Darryl Weatherhead. (2005b). “Is Cheap Talk Effective at Eliminating Hypothetical Bias in a Provision Point Mechanism?” Environmental and Resource Economics 30(3), 327–343.

Neil, Helen. (1995). “The Context for Substitutes in CVM Studies: Some Empirical Observations,” Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 29, 393–397.

Poe, Gregory L., Jeremy E. Clark, Daniel Rondeau, and William D. Schulze. (2002). “Provision Point Mechanisms and Field Validity Tests of Contingent Valuation,” Environmental and Resource Economics 23, 105–131.

Tversky, Amos and Daniel Kahneman. (1974). “Judgement Under Uncertainty,” Science 185, 1122–1131.

Viscusi, W. Kip and Charles J. O’Connor. (1984). “Adaptive Responses to Chemical Labeling: Are Workers Bayesian Decision Makers?” American Economic Review 74(5), 942–956.

Whitehead, John C. (2002). “Incentive Incompatibility and Starting-Point Bias in Iterative Valuation Questions,” Land Economics 78(2), 285–297.

Woolridge, Jeffrey M. (2002). Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Support from the Paul Lowham Research Fund is gratefully appreciated. We thank Chris McIntosh and NeilWilmot for their assistance with the experiments. Helpful comments on earlier drafts were received from Don McLeod and participants at the American Agricultural Economic Association meetings, Western Agricultural Economic Association annual meetings, the joint U.S. Forest Service / Colorado State University seminar series, University of Kentucky, and the CU Environmental and Resource Economics Workshop.

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Appendix 1: Derivation of the Bayesian weighted-average updating function

Start by considering Bayes’ formula

where ∝ stands for “proportional to” as the marginal distribution for τ is dropped. This is standard in Bayesian analysis. Now let the conditional and prior distributions be

The posterior distribution is then

which after expanding the squared terms and dropping constants gives

Finally, we complete the square in WTP to get

This implies that the mean of the posterior distribution (or the updated WTP value) is

which if we define \(\alpha=\sigma_{h}^{2}/\left(\sigma_{g}^{2}+\sigma_{h}^{2}\right)\), can be written as

1.2 Appendix 2: Experimental instructions for NCT and CT treatments

1.2.1 Instructions

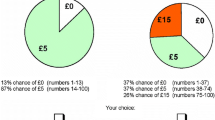

This is an experiment on how people make investment decisions. There are no right or wrong decisions. You have been given $10 to participate. This is yours to keep. You will not be paid anything more. Before the experiment begins, an example of how the experiment works is described. The actual experiment will be conducted after going through this example.

Suppose there are five people, each of whom is given $2 that he or she can invest. The individuals have made the following decisions:

-

Person #1—Invests nothing.

-

Persons #2 and #3—Invest $1 each.

-

Persons #4 and #5—Invest $2 each.

This results in a total of $6 invested from the five people, for an average investment of $6/5 individuals = $1.20. Using the table below, we can now calculate the return on the investment for each person.

Payout Chart—This is only an example

Average group investment | Range of payouts based on your investment choice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

“YES, I’ll invest” | “NO, I won’t invest” | |||||

Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | |

Greater than $0; less than or equal to $1 | $0 | $1 | $2 | $1 | $2 | $3 |

Greater than $1; less than or equal to $2 | $1 | $2 | $3 | $2 | $3 | $4 |

Begin by noting that each person’s payout range is determined in part by his or her investment choice and the average investment of the group. The average investment of $1.20 falls between $1 and $2 so we can focus on the second row of numbers in the table. The exact payout is then determined by the roll of a die. The roll of the die gives equal chances to the Min, Mid and Max payouts. For both the “YES” and “NO” columns, if a 1 or 2 is rolled the Min is paid; if a 3 or 4 is rolled the Mid is paid; and if a 5 or 6 is rolled the Max is paid.

For example, assume a “3” is rolled, so the Mid payout occurs. Person #1 invested nothing. The average group investment was $1.20. Therefore, the person receives a final payout of $3 ($3 payout less $0 invested). Persons #2 and #3 each invested $1. They receive a payout of $2, and their net return is $1 ($2 payout less $1 invested). Persons #4 and #5 each invested $2 and also receive a final payout of $2. Their net return is zero.

Are there any questions before we begin?

1.2.2 Experiment

1.2.2.1 Directions

Use the payout chart below to decide whether to hypothetically invest all, part, or none of your $10. If this experiment were for real, your payout range would be determined by your investment choice and the average investment of the group. (Note that if the total group investment is zero, the payout is zero to everyone.) The exact payout would be determined by the roll of a die. For both the YES and NO columns, if a 1 or 2 is rolled the Min is paid; if a 3 or 4 is rolled the Mid is paid; and if a 5 or 6 is rolled the Max is paid.

Payout Chart

Average group investment | Range of payouts based on your investment choice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

“YES, I’ll invest” | “NO, I won’t invest” | |||||

Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | |

Greater than $0; less than or equal to $2 | $0 | $1 | $2 | $1 | $2 | $3 |

Greater than $2; less than or equal to $4 | $3 | $4 | $5 | $4 | $5 | $6 |

Greater than $4; less than or equal to $6 | $6 | $7 | $8 | $7 | $8 | $9 |

Greater than $6; less than or equal to $8 | $9 | $10 | $11 | $10 | $11 | $12 |

Greater than $8; less than or equal to $10 | $12 | $13 | $14 | $13 | $14 | $15 |

(No cheap talk) Experiment (page 2)

The payout chart below is reproduced from the previous page in order to help you answer the following question.

Payout Chart

Average group investment | Range of payouts based on your investment choice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

“YES, I’ll invest” | “NO, I won’t invest” | |||||

Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | |

Greater than $0; less than or equal to $2 | $0 | $1 | $2 | $1 | $2 | $3 |

Greater than $2; less than or equal to $4 | $3 | $4 | $5 | $4 | $5 | $6 |

Greater than $4; less than or equal to $6 | $6 | $7 | $8 | $7 | $8 | $9 |

Greater than $6; less than or equal to $8 | $9 | $10 | $11 | $10 | $11 | $12 |

Greater than $8; less than or equal to $10 | $12 | $13 | $14 | $13 | $14 | $15 |

(Cheap talk) Experiment (page 2)

The payout chart below is reproduced from the previous page in order to help you answer the following question.

Payout Chart

Average group investment | Range of payouts based on your investment choice | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

“YES, I’ll invest” | “NO, I won’t invest” | |||||

Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | Min payout | Mid payout | Max payout | |

Greater than $0; less than or equal to $2 | $0 | $1 | $2 | $1 | $2 | $3 |

Greater than $2; less than or equal to $4 | $3 | $4 | $5 | $4 | $5 | $6 |

Greater than $4; less than or equal to $6 | $6 | $7 | $8 | $7 | $8 | $9 |

Greater than $6; less than or equal to $8 | $9 | $10 | $11 | $10 | $11 | $12 |

Greater than $8; less than or equal to $10 | $12 | $13 | $14 | $13 | $14 | $15 |

Before answering the next question please note that in previous runs of this experiment we found that people typically overstate their true willingness to invest by approximately $2.00 when asked to do so in a hypothetical setting like this. Please keep this in mind when answering the next question.

1.3 Demographic questions

Please answer the following questions to the best of your ability. These questions are very important to us. Remember that all information is completely anonymous and confidential.

-

1.

Gender: Male

Female

Female

-

2.

Age_____________

-

3.

Class: Freshman

Sophomore

Junior

Senior

Graduate

-

4.

Cumulative GPA _____________

-

5.

Have you declared a major?

Yes

No

No

If yes, what is your major? __________________________

-

6.

In which range do you think your before-tax annual income falls (income includes wages, salary, and money from parents but excludes student loans)?

Less than $10,000.

Less than $10,000. Greater than $10,000 but less than $20,000.

Greater than $10,000 but less than $20,000. Greater than $20,000 but less than $30,000.

Greater than $20,000 but less than $30,000. Greater than $30,000.

Greater than $30,000. -

7.

Which would you choose?

$10 with certainty.

$10 with certainty. 50% chance of $0; 50% chance of $20.

50% chance of $0; 50% chance of $20. I’m indifferent between the two choices above.

I’m indifferent between the two choices above.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aadland, D.M., Caplan, A.J. & Phillips, O.R. A Bayesian examination of information and uncertainty in contingent valuation. J Risk Uncertainty 35, 149–178 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9022-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-007-9022-9

Female

Female