Abstract

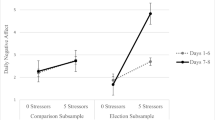

Across two studies, we examined predictors of voters’ worry about the outcome of a political election, thus testing the application of the uncertainty navigation model to political waiting periods. Using a theoretically-grounded set of predictors, we assessed voters who preferred either the Democrats or Republicans to control the House of Representatives following the 2018 U.S. midterm election (N = 376) and Trump and Clinton voters leading up to the 2016 U.S. presidential election (N = 669). Findings generally supported the predictions of the model, such that people worried more as Election Day approached, as did people who saw the election outcome as more important, who believed it was more likely their preferred candidate would lose (Study 2), and who had a set of worry-exacerbating traits. Taken together, the findings provide considerable insight into the dynamics of worry during stressful waiting periods and support the generalizability of the uncertainty navigation model to political contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

To be clear, the uncertainty navigation model is not a model of worry’s nature or function. Instead, it was developed to provide a framework for understanding how people feel and cope when they are waiting for important news. Worry is an inevitable part of that experience, and thus the model makes some predictions about the circumstances under which worry is most likely to arise (within the broader context of uncertain waiting periods). It is these predictions we test in the present paper.

Although this study was run after Study 2, which examined these processes in the 2016 U.S. presidential election, we present the studies in this order in the interest of the flow of the manuscript, such that Study 1 is followed by a larger and more complex Study 2 that included additional predictors.

For this analysis and all other multiple regression analyses in this paper, all variables were entered in the same step using the enter method.

No two predictor variables were correlated greater than r = |.49|, thus providing reassurance against multicollinearity concerns. We also inspected the residual plots for all multiple regression analyses and saw no cause for concern regarding non-normality or non-linear associations. Results were nearly identical when corrected for potential heteroscedasticity.

The possibility of repeat participation was due to a combination of an error on our part in neglecting to prevent repeat responses within the survey and the fact that we had to post several “batches” (essentially, versions of the study) on mTurk.

We tested the possibility that participants may have differed in notable ways across weeks. We ran one-way ANOVAs (continuous variables) and Chi square tests (categorical variables) comparing the eight time-based groups on demographic variables, religiosity, political orientation, and candidate preference. Only education and religiosity differed across groups. Importantly, neither education nor religiosity was notably correlated with worry, rs < .07, ps > .08.

Although we cannot be certain whether the validated properties of the LOT-R were retained with the missing item, a comparison between the results of Studies 1 and 2 provides reassurance that the measure worked in substantively the same way across studies.

These findings were consistent when examining the relationship between each individual social group (friends, family, coworkers, and acquaintances) and worry.

No two predictor variables were correlated greater than r = .43, thus providing reassurance against multicollinearity concerns. We also once again inspected residual plots, finding no cause for concern, and results were nearly identical when correcting for potential heteroscedasticity.

In Study 1, a regression analysis predicting worry from perceived importance (β = .20, p < .001) and political engagement (β = .33, p < .001) suggests that both variables are independent predictors of worry. In Study 2, the same regression analysis revealed that only perceived importance (β = .29, p < .001) and not engagement (β = − .002, p = .96) independently predicted worry.

References

Behar, E., Zuellig, A. R., & Borkovec, T. D. (2005). Thought and imaginal activity during worry and trauma recall. Behavior Therapy, 36(2), 157–168.

Bjorvatn, C., Eide, G. E., Hanestad, B. R., Øyen, N., Havik, O. E., Carlsson, A., et al. (2007). Risk perception, worry and satisfaction related to genetic counseling for hereditary cancer. Journal of Genetic Counseling, 16(2), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10897-006-9061-4.

Boelen, P. A., & Reijntjes, A. (2009). Intolerance of uncertainty and social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(1), 130–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.04.007.

Borkovec, T. D., Robinson, E., Pruzinsky, T., & DePree, J. A. (1983). Preliminary exploration of worry: Some characteristics and processes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 21(1), 9–16.

Borkovec, T. D., & Roemer, L. (1995). Perceived functions of worry among generalized anxiety disorder subjects: Distraction from more emotionally distressing topics? Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 26(1), 25–30.

Boswell, J. F., Thompson-Hollands, J., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2013). Intolerance of uncertainty: A common factor in the treatment of emotional disorders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(6), 630–645.

Bränström, R., Kasparian, N. A., Chang, Y. M., Affleck, P., Tibben, A., Aspinwall, L. G., … & Bruno, W. (2010). Predictors of sun protection behaviors and severe sunburn in an international online study. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention Biomarkers, 19(9), 2199–2210. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-10-0196.

Brewer, N. T., Weinstein, N. D., Cuite, C. L., & Herrington, J. E. (2004). Risk perceptions and their relation to risk behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 27(2), 125–130. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm2702_7.

Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. J. (2002). The intolerance of uncertainty scale: Psychometric properties of the English version. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 40(8), 931–945. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(01)00092-4.

Buhr, K., & Dugas, M. J. (2009). The role of fear of anxiety and intolerance of uncertainty in worry: An experimental manipulation. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 47(3), 215–223.

Carleton, R. N., Norton, M. P. J., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Fearing the unknown: A short version of the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.03.014.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Segerstrom, S. C. (2010). Optimism. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.01.006.

Chapman, G. B., & Coups, E. J. (2006). Emotions and preventive health behavior: Worry, regret, and influenza vaccination. Health Psychology, 25(1), 82–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.82.

Chapman, L. K., Kertz, S. J., & Woodruff-Borden, J. (2009). A structural equation model analysis of perceived control and psychological distress on worry among African American and European American young adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23(1), 69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.03.018.

Cuite, C. L., Brewer, N., Weinstein, N., Herrington, J., & Hayes, N. (2000). Illness-specific worry as a predictor of intentions to vaccinate against Lyme disease. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 22, S12.

Dawson, E., Savitsky, K., & Dunning, D. (2006). “Don’t tell me, I don’t want to know”: Understanding people’s reluctance to obtain medical diagnostic information. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36(3), 751–768. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00028.x.

DiLorenzo, T. A., Schnur, J., Montgomery, G. H., Erblich, J., Winkel, G., & Bovbjerg, D. H. (2006). A model of disease-specific worry in heritable disease: The influence of family history, perceived risk and worry about other illnesses. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9039-y.

Dugas, M. J., Gagnon, F., Ladoceur, R., & Freeston, M. H. (1998). Generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary test of a conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36, 215–226.

Dugas, M. J., Gosselin, P., & Ladouceur, R. (2001). Intolerance of uncertainty and worry: Investigating specificity in a nonclinical sample. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 25(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1005553414688.

Gibbons, A., & Groarke, A. (2016). Can risk and illness perceptions predict breast cancer worry in healthy women? Journal of Health Psychology, 21(9), 2052–2062. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105315570984.

Hay, J. L., McCaul, K. D., & Magnan, R. E. (2006). Does worry about breast cancer predict screening behaviors? A meta-analysis of the prospective evidence. Preventive Medicine, 42(6), 401–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.002.

Howell, J. L., & Sweeny, K. (2016). Is waiting bad for subjective health? Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 39(4), 652–664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-016-9729-7.

Laugesen, N., Dugas, M. J., & Bukowski, W. M. (2003). Understanding adolescent worry: The application of a cognitive model. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021721332181.

Llera, S. J., & Newman, M. G. (2014). Rethinking the role of worry in generalized anxiety disorder: Evidence supporting a model of emotional contrast avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 45(3), 283–299.

McLaughlin, K. A., Borkovec, T. D., & Sibrava, N. J. (2007). The effects of worry and rumination on affect states and cognitive activity. Behavior Therapy, 38(1), 23–38.

National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Generalized anxiety disorder: When worry gets out of control. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/generalized-anxiety-disorder-gad/index.shtml.

Newman, M. G., Llera, S. J., Erickson, T. M., Przeworski, A., & Castonguay, L. G. (2013). Worry and generalized anxiety disorder: A review and theoretical synthesis of evidence on nature, etiology, mechanisms, and treatment. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 275–297. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185544.

Norem, J. K. (2001). Defensive pessimism, optimism, and pessimism. Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice (pp. 77–100). Washington, DC: APA Press.

Norem, J. K., Butler, S., & Pravson, B. (2015, June). Validation of a new Defensive Pessimism Questionnaire-Short Form. In Association for research in personality. Conference conducted at St. Louis, Missouri.

Perkins, A. M., & Corr, P. J. (2005). Can worriers be winners? The association between worrying and job performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(1), 25–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.03.008.

Putwain, D. W., Woods, K. A., & Symes, W. (2010). Personal and situational predictors of test anxiety of students in post-compulsory education. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 80(1), 137–160. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709909X466082.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063–1087. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063.

Siddique, H. I., LaSalle-Ricci, V. H., Glass, C. R., Arnkoff, D. B., & Díaz, R. J. (2006). Worry, optimism, and expectations as predictors of anxiety and performance in the first year of law school. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30(5), 667–676. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-006-9080-3.

Strohmeier, D., Barrett, M., Bora, C., Caravita, S. C., Donghi, E., Dragoti, E., … & Rama, R. (2017). Young people’s engagement with the European Union. Zeitschrift Für Psychologie, 225(4), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.1027/2151-2604/a000314.

Sutton, S. R., & Eiser, J. R. (1990). The decision to wear a seat belt: The role of cognitive factors, fear and prior behaviour. Psychology and Health, 4(2), 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449008408145.

Sweeny, K., & Andrews, S. E. (2014). Mapping individual differences in the experience of a waiting period. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(6), 1015–1030. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036031.

Sweeny, K., Andrews, S. E., Nelson, S. K., & Robbins, M. L. (2015). Waiting for a baby: Navigating uncertainty in recollections of trying to conceive. Social Science and Medicine, 141, 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.031.

Sweeny, K., Carroll, P. J., & Shepperd, J. A. (2006). Thinking about the future: Is optimism always best? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15, 302–306.

Sweeny, K., & Cavanaugh, A. G. (2012). Waiting is the hardest part: A model of uncertainty navigation in the context of health. Health Psychology Review, 6(2), 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.520112.

Sweeny, K., & Dooley, M. D. (2017). The surprising upsides of worry. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12311.

Sweeny, K., & Falkenstein, A. (2015). Is waiting the hardest part? Comparing the emotional experiences of awaiting and receiving bad news. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 41(11), 1551–1559. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215601407.

Sweeny, K., & Howell, J. L. (2017). Bracing later and coping better: Benefits of mindfulness during a stressful waiting period. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(10), 1399–1414. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672177134.

Sweeny, K., Reynolds, C. A., Falkenstein, A., Andrews, S. E., & Dooley, M. D. (2016). Two definitions of waiting well. Emotion, 16(1), 129–143. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000117.

Taylor, K. M., & Shepperd, J. A. (1998). Bracing for the worst: Severity, testing, and feedback timing as moderators of the optimistic bias. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(9), 915–926.

Tull, M. T., Hahn, K. S., Evans, S. D., Salters-Pedneault, K., & Gratz, K. L. (2011). Examining the role of emotional avoidance in the relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity and worry. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 40(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2010.515187.

United States Election Project. (2016). 2016 November general election turnout rates. Retrieved March 3, 2017, from http://www.electproject.org/2016g.

van der Plight, J., Otten, W., Richard, R., & van der Velde, F. W. (1993). Perceived risk of AIDS: Unrealistic optimism and self-protective action. In J. B. Prior & G. D. Reeder (Eds.), The social psychology of HIV infection (pp. 39–58). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wilson, T. D., Centerbar, D. B., Kermer, D. A., & Gilbert, D. T. (2005). The pleasures of uncertainty: Prolonging positive moods in ways people do not anticipate. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.5.

Zebb, B. J., & Beck, J. G. (1998). Worry versus anxiety: Is there really a difference? Behavior Modification, 22(1), 45–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rankin, K., Sweeny, K. Divided we stand, united we worry: Predictors of worry in anticipation of a political election. Motiv Emot 43, 956–970 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09787-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-019-09787-5