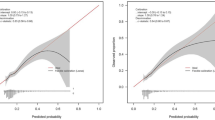

Objectives: Women in poverty may benefit from avoiding closely spaced pregnancies. This study sought to identify predictive factors that could identify women at risk for closely spaced pregnancies. Methods: We studied 20,028 women receiving welfare (cash assistance) from Washington State. Using Cox proportional hazards methods, we estimated the effects of individual- and community-level variables on time from an index birth until a subsequent pregnancy (between June 1992 and December 1999). Prediction models developed in a random half of our data were validated in the other half. Receiver operator characteristic plots appropriate for proportional hazards models were calculated to compare the sensitivity and specificity of each model. Results: At 5 years of follow-up, the most predictive model contained just individual-level variables (age, education, race, marital status, number of prior pregnancies); the area under the receiver operator characteristic curve was 0.66 (.62–.69). The addition of community-level variables (percent in poverty, with a high school degree or higher, Black, Hispanic, in an urban area; female unemployment rate; income inequality) added little predictive ability. Differences were found between women with different individual- and community-level characteristics, but the results suggest that these factors are not strong predictors of pregnancy spacing. Conclusions: Individual- and community-level characteristics are associated with interpregnancy intervals; however, we found little evidence that the selected variables predicted pregnancy interval in a useful manner.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

Nelson MD. Socioeconomic status and childhood mortality in North, Carolina. Am J Public Health 1992;82(8):1131–3.

CDC. Poverty and infant mortality–United, States, 1988. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep 1995;44:922–7.

Mansfield CJ, Wilson JL, Kobrinski EJ, Mitchell J. Premature mortality in the United States: The roles of geographic area, socioeconomic status, household type, and availability of medical care. Am J Public Health 1999;89(6):893–8.

Aber JL, Bennett NG, Conley DC, Li J. The effects of poverty on child health and development. Annu Rev Public Health 1997;18: 463–83.

Harris KM. Life after welfare: Women, work, and repeat dependency. Am Sociol Rev 1996;61:407–26.

Stewart J, Dooley MD. The duration of spells on welfare and off welfare among lone mothers in Ontario. Can Public Pol 1999;25:S47–S72.

Zhu BP, Rolfs RT, Nangle BE, Horan JM. Effect of the interval between pregnancies on perinatal outcomes. New Engl J Med 1999;340(8):589–94.

Wineberg H. The timing of the second birth. Sociol Soc Res 1988;72:96–101.

CDC. Risk factors for short interpregnancy interval—Utah, June 1996–June 1997. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Rep 1998;47:930–4.

Klerman LV, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL. The impact of short interpregnancy intervals on pregnancy outcomes in a low-income population. Am J Public Health 1998;88:1182–5.

Kalmuss DS, Namerow PB. Subsequent childbearing among teenage mothers: The determinants of a closely spaced second birth. Family Plann Perspect 1994;26:149–53, 159.

Manlove J, Mariner C, Papillo AR. Subsequent fertility among teen mothers: Longitudinal analyses of recent national data. J Marriage Family 2000;62:430–48.

Mott FL. The pace of repeated childbearing among young American mothers. Family Plann Perspect 1986;18:5–12.

Mosher WD, Deang LP, Bramlett MD. Community environment and women's health outcomes: Contextual data. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 2003;23(23).

Gold R, Kawachi I, Kennedy B, Lynch J, Connell F. Ecological analysis of teen birth rates: Association with community income and income inequality. Matern Child Health J 2001;5:161–7.

Gold R, Kennedy B, Connell F, Kawachi I. Teen births, income inequality, and social capital: Developing an understanding of the causal pathway. Health Place 2002;8:77–83.

Kirby D, Coyle K, Gould JB. Manifestations of poverty and birthrates among young teenagers in California ZIP code areas. Family Plann Perspect 2001;33:63–9.

Averett SL, Rees DI, Argys LM. The impact of government policies and neighborhood characteristics on teenage sexual activity and contraceptive use. Am J Public Health 2002;92:773–8.

Crane J. The epidemic theory of ghettos and neighborhood effects on dropping out and teenage childbearing. Am J Sociol 1991;96:1226–59.

Brewster KL, Billy JOG, Grady WR. Social context and adolescent behavior: The impact of community on the transition to sexual activity. Soc Forces 1993;71:713–40.

Brewster KL. Neighborhood context and the transition to sexual activity among young black women. Demography 1994;31:603–13.

Billy JOG, Moore DE. A multilevel analysis of marital and nonmarital fertility in the US. Soc Forces 1992;70:977–1011.

Cawthon ML, Kenny F, Schrager L. The, First Steps, Expansion Group: A Study of Women, Newly Eligible for Medicaid, Through Expanded, Eligibility. First Steps Database, Office of Research and Data Analysis, Planning, Research and Development. 1992. Washington State Department of Social and Health, Services. Olympia, WA.

Gold R, Connell F, Heagerty P, Bezruchka S, Davis R, Cawthon ML. Income inequality and pregnancy spacing. Soc Sci Med 2004;59:1117–26.

Kotelchuck, M, Costello CA, Wise PH. Race differences in utilization of prenatal care services in the U.S. Handout: SAS, Computational Program. Presented at the 115th Annual, Meeting of the American, Public Health, Association; October 18–21, 1987; New Orleans, LA (Modified 11/91).

SAS Institute, Inc. Copyright © 1999–2001. SAS, Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied, Survival Analysis: Regression, Modeling of Time to Event Data. New York: Wiley, 1999.

Kawachi I, Kennedy BP. The relationship of income inequality to mortality: Does the choice of indicator matter? Soc Sci Med 1997;45:1121–7.

1990 U.S. Census, Summary Tape File STF3.

Atkinson AC. A note on the generalized information criterion for choice of a model. Biometrika 1980;67:413–8.

Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc 1989;84:1074–8.

Diez-Roux AV. The examination of neighborhood effects on health: Conceptual and methodological issues related to the presence of multiple levels of organization. In: Kawachi, I, Berkman LF, editors, Neighborhoods and Health. 2003. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics 2000;56:337–44.

Bennett T, DeClerque Skatrud J, Guild P, Loda F, Klerman LV. Rural adolescent pregnancy: A view from the South. Family Plann Perspect 1997;29:256–60.

Wilson M, Daly M. Life expectancy, economic inequality, homicide, and reproductive timing in Chicago neighborhoods. Br Med J 1997;314:1271–4.

UNICEF. Teenage births in rich nations. Innocenti Report Card, July 2001, Issue 3.

Pepe MS, Janes H, Longton G, Leisenring W, Newcomb P. Limitations of the odds ratio in gauging the performance of a diagnostic, prognostic, or screening marker. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:882–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gold, R., Connell, F.A., Heagerty, P. et al. Predicting Time to Subsequent Pregnancy. Matern Child Health J 9, 219–228 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-005-0005-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-005-0005-7