Abstract

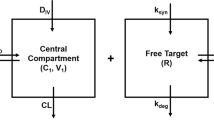

Target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) models have been applied to describe the pharmacokinetics of drugs whose distribution and/or clearance are affected by its target due to high binding affinity and limited capacity. The Michaelis–Menten (M–M) model has also been frequently used to describe the pharmacokinetics of such drugs. The purpose of this study is to investigate conditions for equivalence between M–M and TMDD pharmacokinetic models and provide guidelines for selection between these two approaches. Theoretical derivations were used to determine conditions under which M–M and TMDD pharmacokinetic models are equivalent. Computer simulations and model fitting were conducted to demonstrate these conditions. Typical M–M and TMDD profiles were simulated based on literature data for an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (TRX1) and phenytoin administered intravenously. Both models were fitted to data and goodness of fit criteria were evaluated for model selection. A case study of recombinant human erythropoietin was conducted to qualify results. A rapid binding TMDD model is equivalent to the M–M model if total target density R tot is constant, and R tot K D /(K D + C) 2 ≪ 1 where K D represents the dissociation constant and C is the free drug concentration. Under these conditions, M–M parameters are defined as: V max = k int R tot V c and K m = K D where k int represents an internalization rate constant, and V c is the volume of the central compartment. R tot is constant if and only if k int = k deg, where k deg is a degradation rate constant. If the TMDD model predictions are not sensitive to k int or k deg parameters, the condition of R tot K D /(K D + C) 2 ≪ 1 alone can preserve the equivalence between rapid binding TMDD and M–M models. The model selection process for drugs that exhibit TMDD should involve a full mechanistic model as well as reduced models. The best model should adequately describe the data and have a minimal set of parameters estimated with acceptable precision.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Michaelis L, Menten ML (1913) Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung. Biochem Z 49:333–369

Wagner J (1971) A new generalized nonlinear pharmacokinetic model and its implications. In: Wagner J (ed) Biopharmaceutics and relevant pharmacokinetics drug intelligence publications. Hamilton, IL, pp 302–317

Mager DE, Jusko WJ (2001) General pharmacokinetic model for drugs exhibiting target-mediated drug disposition. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 28:507–532

Mager DE (2006) Target-mediated drug disposition and dynamics. Biochem Pharmacol 72:1–10

Jusko WJ (1989) Pharmacokinetics of capacity-limited systems. J Clin Pharmacol 29:488–493

Bauer RJ, Dedrick RL, White ML, Murray MJ, Garovoy MR (1999) Population pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the anti-CD11a antibody hu1124 in human subjects with psoriasis. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm 27:397–420

Ng CM, Joshi A, Dedrick RL, Garovoy MR, Bauer RJ (2005) Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic-efficacy analysis of efalizumab in patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. Pharm Res 22:1088–1100

Ramakrishnan R, Cheung WK, Wacholtz MC, Minton N, Jusko WJ (2004) Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of recombinant human erythropoietin after single and multiple doses in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol 44:991–1002

Coffey GP, Fox JA, Pippig S, Palmieri S, Reitz B, Gonzales M, Bakshi A, Padilla-Eagar J, Fielder PJ (2005) Tissue distribution and receptor-mediated clearance of anti-CD11a antibody in mice. Drug Metab Dispos 33:623–629

Coffey GP, Stefanich E, Palmieri S, Eckert R, Padilla-Eagar J, Fielder PJ, Pippig S (2004) In vitro internalization, intracellular transport, and clearance of an anti-CD11a antibody (Raptiva) by human T-cells. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:896–904

Ng CM, Stefanich E, Anand BS, Fielder PJ, Vaickus L (2006) Pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics of nondepleting anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (TRX1) in healthy human volunteers. Pharm Res 23:95–103

Kato M, Kamiyama H, Okazaki A, Kumaki K, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y (1997) Mechanism for the nonlinear pharmacokinetics of erythropoietin in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 283:520–527

Chapel S, Veng-Pedersen P, Hohl RJ, Schmidt RL, McGuire EM, Widness JA (2001) Changes in erythropoietin pharmacokinetics following busulfan-induced bone marrow ablation in sheep: evidence for bone marrow as a major erythropoietin elimination pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 298:820–824

Al-Huniti NH, Widness JA, Schmidt RL, Veng-Pedersen P (2004) Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of paradoxal regulation of erythropoietin production in acute anemia. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310:202–208

Ramakrishnan R, Cheung WK, Farrell F, Joffee L, Jusko WJ (2003) Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic modeling of recombinant human erythropoietin after intravenous and subcutaneous dose administration in cynomolgus monkeys. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306:324–331

Woo S, Krzyzanski W, Jusko WJ (2007) Target-mediated pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic model of recombinant human erythropoietin (rHuEPO). J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 34:849–868

Roskos LK, Lum P, Lockbaum P, Schwab G, Yang BB (2006) Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic modeling of pegfilgrastim in healthy subjects. J Clin Pharmacol 46:747–757

Mager DE, Krzyzanski W (2005) Quasi-equilibrium pharmacokinetic model for drugs exhibiting target-mediated drug disposition. Pharm Res 22:1589–1596

Gibiansky L, Gibiansky E, Kakkar T, Ma P (2008) Approximations of the target-mediated drug disposition model and identifiability of model parameters. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 35:573–591

Della Paschoa OE, Mandema JW, Voskuyl RA, Danhof M (1998) Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of the anticonvulsant and electroencephalogram effects of phenytoin in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 284:460–466

Burton ME, Shaw LM, Schentag JJ, Evans WE (2005) Applied pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics: principles of therapeutic drug monitoring. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore

Marathe A, Krzyzanski W, Mager DE (2009) Numerical validation and properties of a rapid binding approximation of a target-mediated drug disposition pharmacokinetic model. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 36:199–219

Akaike H (1974) A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automat Contr 19:716–723

Gabrielsson J, Weiner D (2007) Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data analysis: concepts and applications. Swedish Pharmaceutical Press, Stockholm, Sweden

Abraham AK, Krzyzanski W, Mager DE (2007) Partial derivative-based sensitivity analysis of models describing target-mediated drug disposition. AAPS J 9:E181–E189

Levy G (1994) Pharmacologic target-mediated drug disposition. Clin Pharmacol Ther 56:248–252

Jarsch M, Brandt M, Lanzendorfer M, Haselbeck A (2008) Comparative erythropoietin receptor binding kinetics of C.E.R.A. and epoetin-beta determined by surface plasmon resonance and competition binding assay. Pharmacology 81:63–69

Veng-Pedersen P, Freise KJ, Schmidt RL, Widness JA (2008) Pharmacokinetic differentiation of drug candidates using system analysis and physiological-based modelling. Comparison of C.E.R.A. and erythropoietin. J Pharm Pharmacol 60:1321–1334

Gibiansky L, Gibiansky E (2009) Target-mediated drug disposition model: approximations, identifiability of model parameters and applications to the population pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic modeling of biologics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 5:803–812

Yan X, Mager DE, Krzyzanski W (2008) Selection between Michaelis–Menten and target-mediated drug disposition pharmacokinetic models. AAPS J 10(S2)

Peletier LA, Gabrielsson J (2009) Dynamics of target-mediated drug disposition. Eur J Pharm Sci 38:445–464

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Grant 57980 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Derivation of Wagner equation (Eq. 19)

The Eq. 12a, b can be rearranged to the following form:

Differentiating both sides of Eq. A1 gives:

Solving above equation for dC/dt results in:

Substitution of dC tot /dt from Eq. 13 into Eq. A3 and further replacement of C tot with Eq. A1 yield:

If R tot is constant, then dR tot /dt = 0, and one obtains Eq. 19.

Appendix 2

Theorem: for the TMDD model, R tot is constant if and only if k int = k deg

Proof

-

(a)

Proof of the sufficient condition

At steady state, from Eq. 14 it can be reached:

Hence,

If R tot is constant, Eq. 14 implies:

Replacing k syn with Eq. A6, one can obtain:

From Eq. 12a, b, it can be concluded:

That R tot is constant implies:

Substitution of R tot and R tot0 from Eqs. A9 and A10 to Eq. A11 results in:

Rearrangement of Eq. A12 gives:

Replacing R 0 –R in Eq. A8 with Eq. A13 yields:

Since \( RC_{0} - RC \ne 0 \) after drug administration, the Eq. A14 implies:

-

(b)

Proof of the necessary condition

If \( k_{int} = k_{deg } , \) then Eq. 14 implies:

Replacing k syn in Eq. A16 with Eq. A6 yields:

Substitution of k int with k deg gives:

Given \( R_{tot0} = RC_{0} + R_{0} , \) Eq. A18 reduces to:

Since Eq. A19 starts from initial condition, it can be concluded that:

End of proof.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, X., Mager, D.E. & Krzyzanski, W. Selection between Michaelis–Menten and target-mediated drug disposition pharmacokinetic models. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 37, 25–47 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-009-9142-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10928-009-9142-8