Abstract

Purpose

Theoretical and empirical evidence from basic psychological research suggests that much of affective processing occurs outside of conscious awareness and that this unconscious processing can have profound impacts on attitudes and behaviors. However, research in the management domain examining unconscious affective processing is almost completely absent. To address this void, we examined the role of unconsciously derived affect in work-related judgments and behaviors.

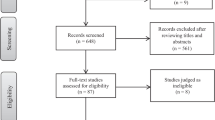

Design/Methodology/Approach

In two studies, participants were primed with subliminal affective cues while performing work-related tasks.

Findings

Across the two studies, the results showed that positively valenced stimuli impacted reports of task satisfaction and performance on some, but not all, types of tasks. The effects of this unconsciously derived affect generally remained even when participants were explicitly told that they would be exposed to these primes.

Implications

This study demonstrates the potential importance of unconsciously derived affect for work-related outcomes. The results provide initial evidence that affect that emerges through sources outside of conscious awareness can impact individuals’ feelings about, and performance on, work-related tasks. This finding may help leaders and employees to make the work environment more conducive to serving employee and organizational objectives.

Originality/Value

This is an initial examination of the effects of unconsciously derived affect on reactions to, and performance on, work-relevant tasks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In well-being research, negative affect scores are routinely subtracted from positive affect scores to form an overall affect score (e.g., Diener 2009; Diener et al. 2012; Robinson et al. 1991; Van Schuur and Kruijtbosch 1995). The resulting affect score is called the “affect balance,” which represents one’s overall experienced psychological well-being at a given point in time (Bradburn 1969). Individuals with high affect balance were said to be in an overall affective mood state whereas those with low affect balance were said to have an overall negative affective state. Bradbum’s (1969) approach (i.e., compute the difference score between positive affect and negative affect) to measure overall affect has proven to be valid, in that the difference score correlates more strongly with two other prominent indicators of well-being, happiness and life satisfaction, than does either the positive or negative affect score, respectively (Bradburn 1969; Harding 1982). In addition, it has been suggested that one’s affective state is composed of both positive and negative states, and thus is better represented by a composite index (e.g., the difference score) than by either positive affect or negative affect separately (Robinson et al. 1991). Although previous research has suggested that positive and negative affect are distinct factors (e.g., Warr et al. 1983; Watson and Tellegen 1985, but also see Diener et al. 1985; Russell and Carroll 1999 for support for the bipolarity of positive and negative affect), Headey et al. (1984) argued that this should not prevent the use of the composite index and that the composite affect score can be better understood if compared with the measurement of intelligence: “general intelligence tests usually have separate sections dealing with quantitative ability and verbal ability, and results for the sections are considered separately… However, it is generally found that, if an overall measure of intelligence is required, it is best to combine the two scores” (p. 116). Thus, to describe individuals’ global affective states, composite scores computed based on positive and negative affect seem most appropriate. For these reasons and considerations, we computed the difference score between positive affect and negative affect and used it as a measure of participants’ overall affective state during the study (Bradburn 1969; van Schuur and Kruijtbosch 1995).

Univariate analyses showed that those in the positive condition liked the proofreading task more than did those in the negative condition (p < 0.05). No significant difference was found for the creative task.

Creativity has also been operationalized as the product of novelty and usefulness in previous research (Zhou and Oldham 2001). Thus, we also ran an ANOVA using the product of novelty and usefulness as the dependent variable. The result showed no significant difference among the three conditions, F (2,105) = 1.33, p > 0.05.

Univariate analyses showed that both those in the primed condition (p < 0.05) and those in the primed-and-told condition (p < 0.05) liked the proofreading task more than did those in the control condition. No significant difference was found for the creative tasks.

Again, we also ran an ANOVA using the product of novelty and usefulness as the dependent variable for each task. Results yielded a significant effect for the brainstorming task, F (2,101) = 3.56, p < 0.05, but a non-significant effect for the problem-solving task, F (2,101) = .07, p > 0.05. Post-hoc comparisons revealed that participants in the primed condition had higher creativity scores than those in the control condition (p < 0.05).

We thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out this possibility.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this future direction.

We conducted regression analyses predicting post-study affect from condition, controlling for pre-study affect. These analyses revealed that, in Study 1, the effect of the condition was not significant at p < 0.05 for either positive affect, F (2,105) = 32.34, or negative affect, F (2,105) = 20.71. In Study 2, the effect of the condition was significant at p < 0.05 for positive affect, F (2,102) = 10.92, but not significant for negative affect, F (2,102) = 12.14.

References

Alloy, L. B., Abramson, L. Y., & Viscusi, D. (1981). Induced mood and the illusion of control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41, 1129–1140. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.41.6.1129.

Amabile, T. M. (1982). Social psychology of creativity: A consensual assessment technique. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 997–1013. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.43.5.997.

Ambady, N., & Gray, H. M. (2002). On being sad and mistaken: Mood effects on the accuracy of thin-slice judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 947–961. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.947.

Baas, M., De Dreu, C. K. W., & Nijstad, B. A. (2008). A meta-analysis of 25 years of mood-creativity research: hedonic tone, activation, or regulatory focus? Psychological Bulletin, 134, 779–806. doi:10.1037/a0012815.

Baker, J. R., & Doran, M. S. (2002). Human resource management: In-basket exercises for school administrators. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Pub Inc.

Bargh, J. A. (2006). What have we been priming all these years? On the development, mechanisms, and ecology of unconscious social behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 147–168. doi:10.1002/ejsp.336.

Bargh, J. A. (2007). Social psychology and the unconscious: The automaticity of higher mental processes. New York: Psychology Press.

Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. L. (1999). The unbearable automaticity of being. American Psychologist, 54, 462–479. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.7.462.

Barling, J., & MacEwen, K. E. (1991). Maternal employment experiences, attention problems and behavioral performance: A mediational model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 12, 495–505. doi:10.1002/job.4030120604.

Barsade, S., Brief, A., & Spataro, S. (2003). The affective revolution in organizational behavior: the emergence of a paradigm. In J. Greenbrg (Ed.), Organizational Behavior: The State of the Science (pp. 3–52). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Barsade, S. G., Ramarajan, L., & Westen, D. (2009). Implicit affect in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 29, 135–162. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2009.06.008.

Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 1054–1068.

Berridge, K. C., & Winkielman, P. (2003). What is an unconscious emotion? (The case for unconscious “liking”). Cognition and Emotion, 17, 181–211. doi:10.1080/02699930302289.

Bolls, P. D., Lang, A., & Potter, R. F. (2001). The effects of message valence and listener arousal on attention, memory, and facial muscular responses to radio advertisements. Communication Research, 28, 627–651. doi:10.1177/009365001028005003.

Bradburn, N. M. (1969). The structure of psychological well-being. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Bradley, M. M., Greenwald, M. K., Petry, M. C., & Lang, P. J. (1992). Remembering pictures: Pleasure and arousal in memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 379–390. doi:10.1037//0278-7393.18.2.379.

Brief, A. P., & Weiss, H. M. (2002). Affect in the workplace. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 279–307. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135156.

Chartrand, T. L., Baaren, R. B. V., & Bargh, J. A. (2006). Linking automatic evaluation to mood and information processing style: Consequences for experienced affect, impression formation, and stereotyping. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 135, 70–77. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.135.1.70.

Chartrand, T. L., & Bargh, J. A. (2002). Unconscious motivations: Their activation, operation, and consequences. In A. Tesser, D. Stapel, & J. Wood (Eds.), Self and motivation: Emerging psychological perspectives (pp. 13–41). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Clore, G., & Colcombe, S. (2003). The parallel worlds of affective concepts and feelings. In J. Musch & K. C. Klauer (Eds.), The psychology of evaluation (pp. 169–188). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Dalal, R. S., Lam, H., Weiss, H. M., Welch, E. R., & Hulin, C. L. (2009). A within-person approach to work behavior and performance: Concurrent and lagged citizenship- counterproductivity associations, and dynamic relationships with affect and overall job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 52, 1051–1066. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2009.44636148.

Davis, M. A. (2009). Understanding the relationship between mood and creativity: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 100, 25–38. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2008.04.001.

Diener, E. (2009). Assessing well-being: The collected works of Ed Diener. Dordrecht: Springer.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Fujita, F., Tay, L., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2012). Purpose, mood, and pleasure in predicting satisfaction judgments. Social Indicators Research, 105, 333–341.

Elsbach, K. D., & Pratt, M. G. (2008). The physical environment in organizations. In J. P. Walsh & A. P. Brief (Eds.), Annals of the Academy of Management (pp. 181–224). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden and build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218.

Freydefont, L., Gendolla, G. H. E., & Silvestrini, N. (2012). Beyond valence: The differential effect of masked anger and sadness stimuli on effort-related cardiac response. Psychophysiology, 49, 665–671. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01340.x.

Gasper, K., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Attending to the big picture: Mood and global versus local processing of visual information. Psychological Science, 13, 33–39. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00406.

Gendolla, G. H. E. (2012). Implicit affect primes effort: Theory and research on cardiovascular response. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 86, 123–135. doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2012.05.003.

George, J. M. (2009). The illusion of will in organizational behavior research: Nonconscious processes and job design. Journal of Management, 35, 1318–1339. doi:10.1177/0149206309346337.

George, J. M., & Zhou, J. (2002). Understanding when bad moods foster creativity and good ones don’t: The role of context and clarity of feelings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 687–697. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.687.

Harding, S. D. (1982). Psychological well-being in Great Britain: An evaluation of the Bradburn Affect Balance Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 3, 167–175.

Hassin, R. R., Uleman, J. S., & Bargh, J. A. (2005). The new unconscious. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Headey, B., Holstrom, E., & Wearing, A. (1984). Well-being and ill-being: Different dimensions? Social Indicators Research, 14, 115–140.

Huberty, C. J., & Morris, J. D. (1989). Multivariate analysis versus multiple univariate analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 302–308. doi:10.1037/10109-030.

Johnson, S. K., & Johnson, C. S. (2009). The secret life of mood: Causes and consequences of unconscious affect at work. In C. E. Hartel (Ed.), Emotions in groups, organizations and cultures (pp. 103–121). Bingley, UK: JAI Press.

Johnson, R. E., Tolentino, A. L., Rodopman, O. B., & Cho, E. (2010). We (sometimes) know not how we feel: Predicting work behaviors with an implicit measure of trait affectivity. Personnel Psychology, 63, 197–219. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.2009.01166.x.

Kaufmann, G. (2003). Expanding the mood–creativity equation. Creativity Research Journal, 15, 131–135. doi:10.1207/S15326934CRJ152&3_03.

Lambie, J. A., & Marcel, A. J. (2002). Consciousness and the varieties of emotion experience: A theoretical framework. Psychological Review, 109, 219–259. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.2.219.

Lasauskaite, R., Gendolla, G. H. E., & Silvestrini, N. (2013). Do sadness-primes make me work harder because they make me sad? Cognition and Emotion, 27, 158–165. doi:10.1080/02699931.2012.689756.

Leventhal, H., & Scherer, K. (1987). The relationship of emotion to cognition: a functional approach to semantic controversy. Cognition and Emotion, 1, 3–28. doi:10.1080/02699938708408361.

Levine, L. J., & Burgess, S. L. (1997). Beyond general arousal: Effects of specific emotions on memory. Social Cognition, 15, 157–181. doi:10.1521/soco.1997.15.3.157.

Liddell, B. J., Williams, L. M., Rathjen, J., Shevrin, H., & Gordon, E. (2004). A temporal dissociation of subliminal versus supraliminal fear perception: An event-related potential study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16, 479–486. doi:10.1162/089892904322926809.

Monahan, J. L., Murphy, S. T., & Zajonc, R. B. (2000). Subliminal mere exposure: Specific, general, and diffuse effects. Psychological Science, 11, 462–466. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.00289.

Nielsen, L., & Kaszniak, A. W. (2007). Conceptual, theoretical, and methodological issues in inferring subjective emotional experience: Recommendations for researchers. In J. J. B. Allen & J. Coan (Eds.), The Handbook of Emotion Elicitation and Assessment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Oldham, G. R., Cummings, A., Mischel, L. J., Schmidtke, J. M., & Zhou, J. (1995). Listen while you work? Quasi-experimental relations between personal-stereo handset use and employee work responses. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 547–564. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.80.5.547.

Quirin, M., Kazén, M., & Kuhl, J. (2009). When nonsense sounds happy or sad: The implicit positive and negative affect test (IPANAT). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97, 500–516. doi:10.1037/a0016063.

Ravaja, N. (2004). Effects of image motion on a small screen on emotion, attention, and memory: Moving face vs. static face newscaster. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 48, 108–133. doi:10.1207/s15506878jobem4801_6.

Ravaja, N., Kallinen, K., Saari, T., & Keltikangas-Järvinen, L. (2004). Suboptimal exposure to facial expressions when viewing video messages from a small screen: effects on emotion, attention, and memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology Applied, 10, 120–131. doi:10.1037/1076-898X.10.2.120.

Robinson, J. P., Shaver, P. R., & Wrightsman, L. S. (1991). Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Russell, J. A., & Carroll, J. B. (1999). On the bipolarity of positive and negative affect. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 3–30.

Ruys, K. I., & Stapel, D. A. (2008). How to heat up from the cold: Examining the preconditions for (unconscious) mood effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 94, 777–791. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.94.5.777.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. (1983). Mood, misattribution, and judgments of well-being: Informative and directive influences of affective states. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 513–523. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.3.513.

Schwarz, N., & Clore, G. L. (2003). Mood as information: 20 years later. Psychological Inquiry, 14, 296–303. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1403&4_20.

Shalley, C. E. (1991). Effects of productivity goals, creativity goals, and personal discretion on individual creativity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 179–185. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.76.2.179.

Shantz, A., & Latham, G. P. (2009). An exploratory field experiment of the effect of subconscious and conscious goals on employee performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 109, 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.01.001.

Silvestrini, N., & Gendolla, G. H. E. (2011a). Do not prime too much: Prime frequency effects of masked affective stimuli on effort-related cardiovascular response. Biological Psychology, 87, 195–199. doi:10.1016/j.biopsycho.2011.01.006.

Silvestrini, N., & Gendolla, G. H. E. (2011b). Masked affective stimuli moderate task difficulty effects on effort-related cardiovascular response. Psychophysiology, 48, 1157–1164. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.2011.01181.x.

Sohlberg, S., Billinghurst, A., & Nylén, S. (1998). Moderation of mood change after subliminal symbiotic stimulation. Four experiments contributing to the further demystification of Silverman’s “mommy and I are one” findings. Journal of Research in Personality, 32, 33–54. doi:10.1006/jrpe. 1997.2199.

Stajkovic, A. D., Locke, E. A., & Blair, E. S. (2006). A first examination of the relationships between primed subconscious goals, assigned conscious goals, and task performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91, 1172–1180. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1172.

Taber, T. D. (1991). Triangulating job attitudes with interpretive and positivist measurement methods. Personnel Psychology, 44, 577–600. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb02404.x.

Van Schuur, W. H., & Kruijtbosch, M. (1995). Measuring subjective well-being: Unfolding the bradburn affect balance scale. Social Indicators Research, 36, 49–74. doi:10.1007/BF01079396.

Velmans, M. (2009). How to define consciousness: And how not to define consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 16, 139–156.

Warr, P., Barter, J., & Brownbridge, G. (1983). On the independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 644–651.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063.

Watson, D., & Tellegen, A. (1985). Toward a consensual structure of mood. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 219–235. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.219.

Weiss, H. M., & Cropanzano, R. (1996). Affective events theory: A theoretical discussion of the structure, causes and consequences of affective experiences at work. Research in Organizational Behavior, 18, 1–74.

Westen, D. (1998). Unconscious thought, feeling and motivation: The end of a century-long debate. In R. F. Bornstein & J. M. Masling (Eds.), Empirical perspectives on the psychoanalytic unconscious (pp. 1–43). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Williams, J. M. G., Mathews, A., & MacLeod, C. (1996). The emotional stroop task and psychopathology. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 3–24.

Winkielman, P., & Berridge, K. C. (2004). Unconscious emotion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 120–123. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00288.x.

Winkielman, P., Berridge, K. C., & Wilbarger, J. L. (2005). Unconscious affective reactions to masked happy versus angry faces influence consumption behavior and judgments of value. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 121–135. doi:10.1177/0146167204271309.

Winkielman, P., Knutson, B., Paulus, M., & Trujillo, J. L. (2007). Affective influence on judgments and decisions: moving towards core mechanisms. Review of General Psychology, 11, 179–192. doi:10.1037/1089-2680.11.2.179.

Winkielman, P., Zajonc, R. B., & Schwarz, N. (1997). Subliminal affective priming resists attributional interventions. Cognition and Emotion, 11, 433–465.

Zemack-Rugar, Y., Bettman, J. R., & Fitzsimons, G. J. (2007). The effect of nonconsciously priming emotion concepts on behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93, 927–939. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.927.

Zhou, J., & Oldham, G. R. (2001). Enhancing creative performance: Effects of expected developmental assessment strategies and creative personality. Journal of Creative Behavior, 35, 151–167.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hu, X., Kaplan, S. The Effects of Unconsciously Derived Affect on Task Satisfaction and Performance. J Bus Psychol 30, 119–135 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9331-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9331-8