Abstract

Background

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a Th2 inflammatory bowel disease characterized by increased IL-5 and IL-13 expression, eosinophilic/neutrophilic infiltration, decreased mucus production, impaired epithelial barrier, and bacterial dysbiosis of the colon. Acetylcholine and nicotine stimulate mucus production and suppress Th2 inflammation through nicotinic receptors in lungs but UC is rarely observed in smokers and the mechanism of the protection is unclear.

Methods

In order to evaluate whether acetylcholine can ameliorate UC-associated pathologies, we employed a mouse model of dextran sodium sulfate (DSS)-induced UC-like conditions, and a group of mice were treated with Pyridostigmine bromide (PB) to increase acetylcholine availability. The effects on colonic tissue morphology, Th2 inflammatory factors, MUC2 mucin, and gut microbiota were analyzed.

Results

DSS challenge damaged the murine colonic architecture, reduced the MUC2 mucin and the tight-junction protein ZO-1. The PB treatment significantly attenuated these DSS-induced responses along with the eosinophilic infiltration and the pro-Th2 inflammatory factors. Moreover, PB inhibited the DSS-induced loss of commensal Clostridia and Flavobacteria, and the gain of pathogenic Erysipelotrichia and Fusobacteria.

Conclusions

Together, these data suggest that in colons of a murine model, PB promotes MUC2 synthesis, suppresses Th2 inflammation and attenuates bacterial dysbiosis therefore, PB has a therapeutic potential in UC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), where inflammation is mainly restricted to colon. The incidence of UC is steadily increasing particularly in the Western world [1]. Although the exact etiology of UC is unclear, increasing evidence suggests that a combination of factors including genetics, environmental agents, immune dysregulation, gut barrier dysfunction, and dysbiosis of the gut microbiota influence the course of the disease [2, 3]. UC is rarely observed in smokers, as nicotine/nicotinic receptor agonists suppress colitis [4]; however, the mechanism by which cigarette smoke/nicotine suppresses the development of UC is unclear. UC is primarily a Th2-mediated IBD associated with eosinophilic infiltration and overproduction of Th2 chemokines/cytokines including eotaxin (CCL11), IL-5, and IL-13 [5,6,7]. In animal models, activation of pulmonary nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) moderates eosinophilic infiltration through suppression of Th2 responses [8]. In mammals, acetylcholine (ACh) is the only known biological ligand for nAChRs, and increasing evidence suggests that ACh and PB—the latter of which increases ACh by inhibiting acetylcholine esterase (AChE)—tend to protect against tissue injury [9, 10]. We and others have shown that nicotine, ACh, and the AChE inhibitor neostigmine bromide (similar to PB) promote mucus formation in human lung epithelial cells through α7-nAChRs [11, 12]. MUC2, the predominant mucin in the gut, plays a critical role in gut homeostasis, and MUC2-deficient mice develop colitis spontaneously [13]; however, unlike MUC5AC in bronchial epithelial cells [14], IL-13 does not always stimulate MUC2 [15]. UC also affects gut microbiota and the integrity of the epithelial barrier in the colon [2, 5, 6]; thus normal fecal microbial transplantation is a promising treatment for UC [16, 17]. As DSS has been found to induce UC-like conditions in a mouse model [18, 19], in this study we examined whether PB attenuated DSS-induced colon pathology in C57BL/6 mice.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Pathogen-free 5–6-week-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). Animals were kept in chambers as described previously [11]. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

DSS and PB Treatment

Mice (8–9 weeks old) were divided into three groups (control, DSS, and DSS+PB) with 6–8 animals/group. PB and DSS were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, USA. Mice were given PB through intraperitoneally implanted Alzet mini-osmotic pumps [20] starting at day 7 prior to DSS treatment and continued until they were euthanized. Mice implanted with mini-osmotic pumps containing sterile saline served as the control. The pumps provided PB at a concentration of 2 mg/day/kg body weight. Colitis was induced by 3.0% (w/v) DSS-containing water. The treatment continued for 7 days; the animals were euthanized and colons harvested on day 8. Animals were weighed daily after DSS treatment. Where indicated, intestines were dissected to obtain ileum, cecum, and colon; tissues were frozen for RNA and protein, and fecal material for bacterial microbiome analysis.

Histochemical Staining and Scoring

Formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections (5 μm) were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for general histology. Histochemical staining with Alcian Blue and periodic acid–Schiff reagent (AB–PAS) was carried out as described previously [21]. Eosinophils and goblet cells were enumerated microscopically. Tissue sections were coded and assessed in a blinded manner. Histological damage was scored as described previously [18]. Briefly, sections were scored for eosinophil infiltration (0–3), with 0 representing less than three eosinophils per field of view at 40× magnification in the lamina propria, 1 for greater than three eosinophils per field of view in the lamina propria, 2 representing confluence of eosinophils extending into the submucosa, and 3 representing confluence of eosinophils present in all tissue layers.

Immunofluorescence Imaging

Deparaffinized and hydrated tissue sections were washed in 0.05% v Brij-35 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and immunostained for antigen expression as described previously [22]. Briefly, the antigens were unmasked and incubated in a blocking solution. The sections were stained with antibodies to ZO-1 (Invitrogen Inc., Carlsbad, CA, USA) or anti-eosinophil antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), or isotype control antibodies. Immunofluorescence images were captured with a BZX700 all-in-one microscope (Keyence Corp., Japan).

qRT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA from frozen mouse colon tissue was isolated using TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Inc., Cincinnati, OH, USA). Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was performed using the StepOnePlus detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the TaqMan One-Step RT-PCR kit containing AmpliTaq Gold® DNA polymerase [23]. Specific primers and probes were obtained from Applied Biosystems. Fold changes in qPCR expression were calculated by the 2(−ΔΔCT) method [24].

Western Blot Analysis

Western blot analysis of eotaxin, IL-5, IL-13 and MUC2 in mice colon homogenates was performed as described previously [23]. Briefly, colon homogenates (70 μg) were fractionated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) for eotaxin, IL-5, and IL-13, and 5% SDS-PAGE for MUC2. After transfer to nitrocellulose membranes, blots were probed with antibodies to eotaxin, IL-5, IL-13, and MUC2 (Abcam), and after stripping were re-probed with anti–β actin antibody.

Histological Grading

The H&E-stained sections were analyzed for histological grading to evaluate the severity of inflammation. The total score ranged from 0 to 14, representing the sum of scores from the following: (1) severity of inflammation, with 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, and 3 = severe; (2) mucosal damage, with 0 = none, 1 = mucosal layer, 2 = submucosa, and 3 = transmural; (3) crypt damage, with 0 = none, 1 = basal one-third damage, 2 = basal two-thirds damage, 3 = crypt lost with intact epithelium, and 4 = crypt and epithelium lost; and (4) percentage involvement, with 0 = none, 1 = ≤25%, 2 = 26–50%, 3 = 51–75%, and 4 = 76–100%, as previously described [25].

Bacterial Microbiome Analysis: Sequencing and 16S DNA Analysis

Fecal contents were collected from the gut encompassing distal cecum and distal sigmoid colon and frozen on dry ice. The fecal matter was lysed using glass beads in a MagNA Lyser tissue disruptor (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) and total DNA was isolated using the DNeasy Powersoil® or AllPrep PowerFecal® DNA isolation kits (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and quantified as described elsewhere [26]. Briefly, the bacterial 16S V4 rDNA region was amplified using fusion primers, and each sample was PCR-amplified with two differently barcoded V4 fusion primers and loaded into the MiSeq cartridge (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The amplicons were sequenced for 250 cycles with custom primers designed for paired-end sequencing. Using the QIIME platform, sequences were quality-filtered and demultiplexed using exact matches to the supplied DNA barcodes. The sequences were searched against the Greengenes reference database and clustered at 97% by UCLUST (closed-reference operational taxonomic unit [OTU] picking). The relative abundance of OTUs constituting a single phylum in treated animals was normalized with the OTUs in controls. The resulting ratios were analyzed using Prism software (GraphPad Software, LA Jolla, CA, USA) to identify changes between groups in the five major bacterial phyla in the microbiome.

Results and Discussion

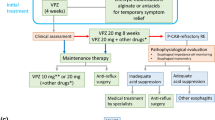

PB Ameliorates the DSS-Induced Increase in IL-5 and Eotaxin

While the exact pathophysiology of UC is unknown, several immune cell types, including neutrophils, eosinophils, and lymphocytes, have been implicated in the disease process [27, 28]. Similar to allergic asthma in the lungs, UC is a Th2 disease where eosinophils and eosinophil-associated proteins play a significant role in the disease pathology [29], and eosinophilic granulocyte infiltration is seen in UC-associated inflammation [5, 30] and implicated in the pathophysiology of UC in humans [31, 32]. Moreover, eosinophils are a therapeutic target for gut inflammation [33]. IL-5 drives the growth of eosinophils, and eotaxin is the most potent chemokine that stimulates eosinophilic infiltration, while IL-13 affects the gut epithelial barrier; these factors are elevated in UC [27, 32], and interestingly, eosinophilic granules contain IL-5, IL-13, and eotaxin [34, 35]. Eotaxin has been established as the chemokine that drives eosinophilic infiltration in UC. We analyzed colonic tissues from control, DSS-treated, and DSS+PB-treated mice for eosinophil infiltration of the tissue. Eosinophils were visualized by immunohistochemistry using an eosinophil-specific antibody that showed that DSS stimulated eosinophilic infiltration of the colon (Fig. 1a, left panel), with a pathology score of > 3.0, which was significantly reduced by PB treatment (Fig. 1a, right panel), indicating that inhibition of AChE partially protects the colon from infiltration by eosinophils. Accumulation of eosinophils at the site of inflammation requires cooperation between IL-5 and eotaxin [36], where IL-5 promotes proliferation and differentiation of eosinophils, and eotaxin is a potent chemoattractant for eosinophils that is increased significantly in UC [5, 32, 33]. We determined the expression of IL-5 and eotaxin by Western blot and/or RT-qPCR analyses. The results showed that DSS doubled the amount of IL-5 protein in the colon, which was significantly reduced by the PB treatment (Fig. 1b). DSS-induced IL-5 levels were comparable to IL-5 mRNA levels observed in rectal biopsy samples from UC patients [5]. Similarly, PB reduced eotaxin protein (Fig. 1c) and eotaxin mRNA (Fig. 1d) levels. DSS treatment has also been found to cause body weight loss in mice [4]. Following DSS treatment, we weighed mice daily. On day 4, DSS-treated animals began to exhibit loss of body weight, and the decrease was statistically significant compared with control mice on day 5. However, on day 5 there was no significant difference in body weight between the control and DSS+PB groups (Fig. 1E). This difference in body weight became significant on day 7/8, but the reduction was lower than in the animals treated with DSS alone ((Fig. 1e). These results suggest that PB slightly but significantly moderates DSS-induced weight loss in mice. Thus, PB appears to attenuate the pro-eosinophilic effects of DSS in the mouse colon through downregulation of IL-5 and eotaxin expression and moderates the DSS-induced loss of body weight.

PB ameliorates the DSS-induced eosinophilic infiltration and increased expression of IL-5 and eotaxin in the colon, and the reduction in body weight. a Colonic tissues from mice treated with DSS alone or PB+DSS were analyzed for eosinophils on H&E-stained sections and were compared with controls (magnification 400×). b Western blot analysis of IL-5 in colonic homogenates (70 µg). Blots were probed for IL-5 and β-actin levels and quantitated as the ratio of IL-5/β-actin following densitometric analysis. c Eotaxin expression by Western blots of colonic homogenates (70 µg) (left panel), densitometric quantitation of eotaxin (right panel). d RT-qPCR analysis of eotaxin mRNA expression in total colonic RNA. e PB effects on DSS-induced body weight reduction on day 8 after DSS treatment. Groups are as follows: Control (Cont), DSS: dextran sodium sulfate-treated, and DSS+PB: DSS and pyridostigmine bromide-treated. Figures are representative of two separate experiments (n = 4–5/group) for A, B, C, and D and one experiment for E (n = 6–8 animals). *≤ 0.01; **≤ 0.001; ***≤ 0.0001

PB Inhibits DSS-Induced IL-13 Expression and Improves Colonic Epithelial Integrity and MUC2 Mucin Expression

UC is predominantly a Th2 inflammatory disease and IL-13 is the key effector cytokine in UC pathogenesis [6, 37], which in excessive concentrations impairs the integrity of colonic epithelium [38,39,40]. In the lung, IL-13 induces airway mucin (MUC5AC) formation [11]; however, unlike the lung, IL-13 does not regulate mucin (MUC2) production in the intestinal epithelial cells [41]. The lamina propria of UC patients produces substantially more IL-13 than normal individuals [28, 42] and neutralization of IL-13 prevents experimental UC and attenuates human UC [37, 43]. Therefore, we analyzed the effects of PB on the IL-13 expression in gut tissues. Western blot analysis indicated that DSS upregulates the expression of IL-13 protein and PB significantly downregulates this response (Fig. 2a). The intestinal barrier consists of epithelial columnar cells connected by intracellular junctions that are covered by mucus. The epithelium and the mucus layer inhibit the invasion of gut mucosa by luminal microbes. Impaired colonic barrier promotes gut inflammation and the thickness of the mucus layer is decreased in active UC patients [44, 45]. Mucus is made by goblet cells, and the major gel-forming mucin in the gut is MUC2 [46]. MUC2 synthesis is defective in UC patients, and variants of MUC2 gene are associated with increased incidence of UC [47]. In UC patients and experimental animals, bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable colonic mucus layer and MUC2 expression is strongly downregulated in UC [48]. MUC2 provides protection against colitis, and MUC2-deficient mice exhibit increased susceptibility to colitis [49, 50]. We compared the expression of MUC2 protein in DSS and DSS+PB colons by Western blot analysis. The results presented in Fig. 2B show that compared to normal colonic tissues, MUC2 protein expression is significantly decreased (p < 0.05) by DSS; however, PB treatment strongly upregulates the expression of MUC2 protein in DSS-treated animals (p < 0.01), and MUC2 expression is even higher (p < 0.05) than the control group. These results suggest that loss of MUC2 protein expression is associated with UC inflammation, and PB promotes MUC2 expression.

PB suppresses DSS-induced IL-13 expression and induces MUC2 expression. a WB analysis of IL-13 in colonic homogenates (70 µg). The blots were probed with anti-IL-13-specific antibody. The bar graph represents quantitation by densitometry (ratio of IL-13/β-actin). b Analysis of MUC2 expression by WB analysis of colon tissue homogenates (70 µg) probed with MUC2-specific antibody. The bar graph is quantitation of MUC2 by densitometry (ratio MUC2/β-actin). Figures are representative of two separate experiments (n = 4–5/group); where *≤ 0.01, **≤ 0.001, and ***≤ 0.0001

Normal functioning of the gut epithelium requires tight junction (TJ) proteins, which provide structural integrity to the tissue by forming a highly polarized barrier with selective paracellular permeability [51]. Histopathologically, UC is associated with disruption of TJ proteins and the TJs are composed of proteins that include occludin, claudins, junctional adhesion molecules, and intracellular scaffold proteins such as zonula occludens (ZO), including ZO-1 [52]. ZO-1 is a scaffolding linker protein that interacts with occludin and is reduced in UC patients [53]. To determine the effects of PB on colonic architecture, colon tissues were stained with H&E and analyzed for histological grading to evaluate the severity of UC. We based the disease severity primarily on histopathological changes in the colon on a scale of 0–14 (see “Materials and methods” section). As assessed by these criteria, Fig. 3a shows that DSS-induced disease severity of 6.33 ± 0.42, which was significantly moderated by PB to 2.67 ± 0.33. Moreover, as seen by immunofluorescence/immunohistochemistry analysis, the DSS-induced reduction in colonic ZO-1 was attenuated by PB treatment (Fig. 3b, in green). These results suggest that PB partially protected mice from DSS-induced disruption of the gut epithelial architecture.

PB ameliorates the colonic epithelial integrity loss and inflammation. a Representative H&E stained colon sections and the histological scoring of pathological severity. The lower panel shows the enlarged images of the inset drawn on upper panels (scale, 50 microns). b Representative colonic expression of ZO-1 as assessed by immunofluorescence analysis. Images show ZO-1 (in green) and DAPI-stained nuclei (in blue). Lower panels show the enlarged images of the inset drawn on upper panels. Image magnification 100× for upper panel and 400× for lower panel. Figures are representative of two separate experiments (n = 4–5/group); where *≤ 0.01, **≤ 0.001, and ***≤ 0.0001

PB Attenuates DSS-Induced Dysbiosis of Microbiota in the Colon

The intestines, particularly the colon, are inhabited by a large number of microorganisms that normally provide symbiotic benefits to the host; however, barrier dysfunction in UC causes unfavorable changes in the composition of gut microbiota (dysbiosis) that facilitates the penetration of colonic mucus layers by these bacteria to induce gut inflammation [13, 38, 54]. Normal gut bacterial microbial community is typically dominated (nearly 95%) by phyla Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes, and Proteobacteria [55], and each phylum has members that are beneficial or pathogenic in the gut. Imbalances in gut microbiota are seen in the DSS-induced UC in mice [56], and recent results suggest that fecal transplants containing normal bacterial microbiota attenuate UC symptoms in patients [17, 57] and in experimental animal models [58].

To determine whether DSS-induced changes in the bacterial composition of the colon are attenuated by PB, we analyzed the colonic 16S V4-rDNA. Figure 4a shows that in a normal mouse colon (CON), Erysipelotrichia, Clostridia, Flavobacteria, and Fusobacteria represent approximately 69%, 14%, 13%, and 4% of all sequences, respectively, and DSS treatment alters this composition to 82%, 3%, 7%, and 8%, respectively. Thus, DSS increases Erysipelotrichia and Fusobacteria and decreases Clostridia and Fusobacteria in the gut. PB treatment nearly restored the normal microbiota composition of Erysipelotrichia, Clostridia, Flavobacteria, and Fusobacteria to about 73%, 12%, 11% and 4%, respectively. The weighted Unifrac principal coordinate analysis of the microbiome data shows that the microbiome from the control animals cluster distinctly compared to the DSS-treated animals (Fig. 4b).

PB attenuates DSS-induced dysbiosis of microbiota in the colon. a Colonic 16S V4-rDNA from various groups was analyzed for sequences specific for Erysipelotrichia, Clostridia, Flavobacteria and Fusobacteria. b The weighted Unifrac principal coordinate analysis of the three groups. Microbiome from the control animals is seen to cluster distinctly compared to DSS-treated animals. The PB+DSS group is seen to cluster with the control group. p-value is 0.01 (control vs. DSS), 0.038 (DSS vs. PB+DSS) and 0.2 (control vs. PB+DSS). Test of significance was a two-sided Student two-sample t test, and non-parametric p-values (exact) were calculated using 999 Monte Carlo permutations. The figure presents the mean distribution of the bacterial types (n = 4–5 colons/group) and is representative of two separate experiments

Clostridia difficile infection is known to recur in UC patients and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality in this population [59]; however, organisms within Clostridia genera are higher in normal gut flora and normal fecal microbiota is used to treat recurrent Clostridia difficile infection [60]. Both Clostridia and Erysipelotrichia belong to phylum Firmicutes, but commensal Clostridia maintains gut homeostasis and moderates Clostridia difficile infection [60, 61]. Commensal Clostridia promotes the development of anti-inflammatory IL-10-producing Fox3p+ T-reg cells in the gut [62,63,64], and defects in the IL-10 or IL-10 receptor are known to promote early onset of UC [65]. On the other hand, Erysipelotrichia increases mucosal permeability and stimulates inflammatory immune responses in the gut [66]. The role of Flavobacteria in the human gut has not been clearly defined; however, Flavobacteria are less abundant in human IBD [67]. Similarly, the function of Fusobacteria in the gut are unknown, but their numbers increase in colorectal cancer [68], and UC increases susceptibility to colon cancer [69]. Therefore, it is likely that PB, through increased acetylcholine levels, (a) increases mucus formation and (b) inhibits the DSS-induced loss of the epithelial barrier function by suppressing IL-13 production. Together, this inhibits the DSS-induced migration of pathogenic bacteria and bacterial dysbiosis in the gut. Thus, PB has the potential to stabilize gut flora and attenuate inflammation associated with UC.

Cholinergic stimuli involving ACh are important in the regulation of gut function, and ACh regulates both motility and mucosal responses in the gut. Recent evidence suggests that ACh and PB tend to be protective against experimental tissue injury. PB restored cardiac autonomic balance in mice and rats after experimental myocardial infarction [9, 70, 71], and heart-specific overexpression of the ACh-synthesizing enzyme choline acetyltransferase was found to protect the myocardium against ischemia-induced injury in mice [72]. PB has also been shown to help some patients with spinal cord injuries [73] and diabetic patients with gastrointestinal disorders [74]. Moreover, release of ACh through electrical stimulation of the vagus nerve ameliorates gut inflammation through nAChRs [75]. We have shown that ACh and neostigmine bromide induce mucus production in airway epithelial cells through α7-nAChRs [11], and nicotine suppresses both inflammatory and adaptive immune responses [76, 77]; interestingly, tobacco smokers were found to be very resistant to UC [78]. In mammals, ACh is the only known biological ligand that reacts with nicotinic as well as muscarinic receptors, and nAChRs on non-neuronal cells respond to very low concentrations of nicotine [11, 79]. Therefore, it is likely that at lower concentrations, ACh reacts primarily with nAChRs thereby protecting the gut from colitis and bacterial dysbiosis and has the potential to suppress UC. Because nAChRs are present on many different cell types, including T cells, monocytes/macrophages, and epithelial cells, at present the identity of the cell type(s) that is/are the primary target of acetylcholine in the gut is unclear. In the lung, bronchial epithelial cells express nAChRs, and acetylcholine, neostigmine bromide, and nicotine promote mucus production from these cells [11, 80]; however, nicotine is known to inhibit Th2 immune responses through its effects on T cells and macrophages [8, 81]. It is therefore likely that the effects of acetylcholine/PB on UC severity involve multiple cell types. Further experiments are needed to identify the target cell type(s) that is/are critical in moderating UC in this model.

Abbreviations

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- PB:

-

Pyridostigmine bromide

- DSS:

-

Dextran sodium sulfate

- nAChR:

-

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- AChe:

-

Acetylcholine esterase

- TJ:

-

Tight junction

- ZO-1:

-

Zona occludin-1

References

Burisch J, Munkholm P. The epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:942–951.

Fakhoury M, Negrulj R, Mooranian A, Al-Salami H. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and treatments. J Inflamm Res. 2014;7:113–120.

de Mattos BR, Garcia MP, Nogueira JB, et al. Inflammatory bowel disease: an overview of immune mechanisms and biological treatments. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:493012.

Hayashi S, Hamada T, Zaidi SF, et al. Nicotine suppresses acute colitis and colonic tumorigenesis associated with chronic colitis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G968–978.

Lampinen M, Waddell A, Ahrens R, Carlson M, Hogan SP. CD14+ CD33+ myeloid cell-CCL11-eosinophil signature in ulcerative colitis. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1061–1070.

Mar JS, LaMere BJ, Lin DL, et al. Disease severity and immune activity relate to distinct interkingdom gut microbiome states in ethnically distinct ulcerative colitis patients. MBio. 2016;7:e01072.

Nemeth ZH, Bogdanovski DA, Barratt-Stopper P, Paglinco SR, Antonioli L, Rolandelli RH. Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis show unique cytokine profiles. Cureus. 2017;9:e1177.

Mishra NC, Rir-Sima-Ah J, Langley RJ, et al. Nicotine primarily suppresses lung Th2 but not goblet cell and muscle cell responses to allergens. J Immunol. 2008;180:7655–7663.

Santos-Almeida FM, Girao H, da Silva CA, Salgado HC, Fazan R Jr. Cholinergic stimulation with pyridostigmine protects myocardial infarcted rats against ischemic-induced arrhythmias and preserves connexin43 protein. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2015;308:H101–H107.

Feriani DJ, Coelho-Junior HJ, de Oliveira J, et al. Pyridostigmine improves the effects of resistance exercise training after myocardial infarction in rats. Front Physiol. 2018;9:53.

Gundavarapu S, Wilder JA, Mishra NC, et al. Role of nicotinic receptors and acetylcholine in mucous cell metaplasia, hyperplasia, and airway mucus formation in vitro and in vivo. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:e711.

Maouche K, Medjber K, Zahm JM, et al. Contribution of alpha7 nicotinic receptor to airway epithelium dysfunction under nicotine exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:4099–4104.

Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, Velcich A, Holm L, Hansson GC. The inner of the two Muc2 mucin-dependent mucus layers in colon is devoid of bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15064–15069.

Kondo M, Tamaoki J, Takeyama K, Nakata J, Nagai A. Interleukin-13 induces goblet cell differentiation in primary cell culture from Guinea pig tracheal epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:536–541.

Ren C, Dokter-Fokkens J, Figueroa Lozano S, et al. Lactic acid bacteria may impact intestinal barrier function by modulating goblet cells. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2018;62:e1700572.

Kunde S, Pham A, Bonczyk S, et al. Safety, tolerability, and clinical response after fecal transplantation in children and young adults with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;56:597–601.

Moayyedi P, Surette MG, Kim PT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission in patients with active ulcerative colitis in a randomized controlled trial. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:e106.

Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Lab Invest. 1993;69:238–249.

Yu XT, Xu YF, Huang YF, et al. Berberrubine attenuates mucosal lesions and inflammation in dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis in mice. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194069.

Singh SP, Kalra R, Puttfarcken P, Kozak A, Tesfaigzi J, Sopori ML. Acute and chronic nicotine exposures modulate the immune system through different pathways. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;164:65–72.

Chand HS, Mebratu YA, Kuehl PJ, Tesfaigzi Y. Blocking Bcl-2 resolves IL-13-mediated mucous cell hyperplasia in a Bik-dependent manner. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:1456–1459.

Hussain SS, George S, Singh S, et al. A small molecule BH3-mimetic suppresses cigarette smoke-induced mucous expression in airway epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:13796.

Singh SP, Chand HS, Gundavarapu S, et al. HIF-1alpha plays a critical role in the gestational sidestream smoke-induced bronchopulmonary dysplasia in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137757.

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408.

Kihara N, de la Fuente SG, Fujino K, Takahashi T, Pappas TN, Mantyh CR. Vanilloid receptor-1 containing primary sensory neurones mediate dextran sulphate sodium induced colitis in rats. Gut. 2003;52:713–719.

Banerjee S, Sindberg G, Wang F, et al. Opioid-induced gut microbial disruption and bile dysregulation leads to gut barrier compromise and sustained systemic inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1418–1428.

Fries W, Comunale S. Ulcerative colitis: pathogenesis. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1373–1382.

Li J, Ueno A, Fort Gasia M, et al. Profiles of lamina propria T helper cell subsets discriminate between ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22:1779–1792.

Spencer LA, Szela CT, Perez SA, et al. Human eosinophils constitutively express multiple Th1, Th2, and immunoregulatory cytokines that are secreted rapidly and differentially. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;85:117–123.

Mishra A. Significance of mouse models in dissecting the mechanism of human eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (EGID). J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2013;2:845–853.

Raab Y, Fredens K, Gerdin B, Hallgren R. Eosinophil activation in ulcerative colitis: studies on mucosal release and localization of eosinophil granule constituents. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1061–1070. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018843104511.

Forbes E, Murase T, Yang M, et al. Immunopathogenesis of experimental ulcerative colitis is mediated by eosinophil peroxidase. J Immunol. 2004;172:5664–5675.

Hogan SP, Rothenberg ME. Review article: the eosinophil as a therapeutic target in gastrointestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:1231–1240.

Schmid-Grendelmeier P, Altznauer F, Fischer B, et al. Eosinophils express functional IL-13 in eosinophilic inflammatory diseases. J Immunol. 2002;169:1021–1027.

Woerly G, Lacy P, Younes AB, et al. Human eosinophils express and release IL-13 following CD28-dependent activation. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:769–779.

Mould AW, Matthaei KI, Young IG, Foster PS. Relationship between interleukin-5 and eotaxin in regulating blood and tissue eosinophilia in mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:1064–1071.

Heller F, Florian P, Bojarski C, et al. Interleukin-13 is the key effector Th2 cytokine in ulcerative colitis that affects epithelial tight junctions, apoptosis, and cell restitution. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:550–564.

Hering NA, Fromm M, Schulzke JD. Determinants of colonic barrier function in inflammatory bowel disease and potential therapeutics. J Physiol. 2012;590:1035–1044.

Boldeanu MV, Silosi I, Ghilusi M, et al. Investigation of inflammatory activity in ulcerative colitis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1345–1351.

Buzza MS, Johnson TA, Conway GD, et al. Inflammatory cytokines down-regulate the barrier-protective prostasin-matriptase proteolytic cascade early in experimental colitis. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:10801–10812.

Takeda K, Hashimoto K, Uchikawa R, Tegoshi T, Yamada M, Arizono N. Direct effects of IL-4/IL-13 and the nematode Nippostrongylus brasiliensis on intestinal epithelial cells in vitro. Parasite Immunol. 2010;32:420–429.

Rosen MJ, Karns R, Vallance JE, et al. Mucosal expression of type 2 and type 17 immune response genes distinguishes ulcerative colitis from colon-only Crohn’s disease in treatment-naive pediatric patients. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1345–1357.

Hoving JC, Cutler AJ, Leeto M, et al. Interleukin 13-mediated colitis in the absence of IL-4Ralpha signalling. Gut. 2017;66:2037–2039.

Strugala V, Dettmar PW, Pearson JP. Thickness and continuity of the adherent colonic mucus barrier in active and quiescent ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:762–769.

Pullan RD, Thomas GA, Rhodes M, et al. Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis. Gut. 1994;35:353–359.

Tytgat KM, Opdam FJ, Einerhand AW, Buller HA, Dekker J. MUC2 is the prominent colonic mucin expressed in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996;38:554–563.

Visschedijk MC, Alberts R, Mucha S, et al. Pooled resequencing of 122 ulcerative colitis genes in a large Dutch cohort suggests population-specific associations of rare variants in MUC2. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0159609.

Dharmani P, Leung P, Chadee K. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha and Muc2 mucin play major roles in disease onset and progression in dextran sodium sulphate-induced colitis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25058.

Kawashima H. Roles of the gel-forming MUC2 mucin and its O-glycosylation in the protection against colitis and colorectal cancer. Biol Pharm Bull. 2012;35:1637–1641.

Van der Sluis M, De Koning BA, De Bruijn AC, et al. Muc2-deficient mice spontaneously develop colitis, indicating that MUC2 is critical for colonic protection. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:117–129.

Okumura R, Takeda K. Maintenance of intestinal homeostasis by mucosal barriers. Inflamm Regen. 2018;38:5.

Kim DY, Furuta GT, Nguyen N, Inage E, Masterson JC. Epithelial claudin proteins and their role in gastrointestinal diseases. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;68:611–614.

Das P, Goswami P, Das TK, et al. Comparative tight junction protein expressions in colonic Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, and tuberculosis: a new perspective. Virchows Arch. 2012;460:261–270.

Johansson ME, Gustafsson JK, Holmen-Larsson J, et al. Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon mucus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2014;63:281–291.

Mahowald MA, Rey FE, Seedorf H, et al. Characterizing a model human gut microbiota composed of members of its two dominant bacterial phyla. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5859–5864.

Osaka T, Moriyama E, Arai S, et al. Meta-analysis of fecal microbiota and metabolites in experimental colitic mice during the inflammatory and healing phases. Nutrients. 2017;9:1329.

Holleran G, Scaldaferri F, Ianiro G, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of patients with ulcerative colitis and other gastrointestinal conditions beyond Clostridium difficile infection: an update. Drugs Today (Barc). 2018;54:123–136.

Yan ZX, Gao XJ, Li T, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in experimental ulcerative colitis reveals associated gut microbial and host metabolic reprogramming. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2018;84:e00434.

Negron ME, Rezaie A, Barkema HW, et al. Ulcerative colitis patients with clostridium difficile are at increased risk of death, colectomy, and postoperative complications: a population-based inception cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:691–704.

Carlucci C, Petrof EO, Allen-Vercoe E. Fecal microbiota-based therapeutics for recurrent clostridium difficile infection, ulcerative colitis and obesity. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:37–45.

Stefka AT, Feehley T, Tripathi P, et al. Commensal bacteria protect against food allergen sensitization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:13145–13150.

Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500:232–236.

Round JL, Mazmanian SK. Inducible Foxp3+ regulatory T-cell development by a commensal bacterium of the intestinal microbiota. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12204–12209.

Geuking MB, Cahenzli J, Lawson MA, et al. Intestinal bacterial colonization induces mutualistic regulatory T cell responses. Immunity. 2011;34:794–806.

Glocker EO, Kotlarz D, Klein C, Shah N, Grimbacher B. IL-10 and IL-10 receptor defects in humans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1246:102–107.

Jakobsson HE, Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Schutte A, et al. The composition of the gut microbiota shapes the colon mucus barrier. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:164–177.

Ng SC, Lam EF, Lam TT, et al. Effect of probiotic bacteria on the intestinal microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:1624–1631.

Park CH, Han DS, Oh YH, Lee AR, Lee YR, Eun CS. Role of Fusobacteria in the serrated pathway of colorectal carcinogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25271.

Binder V, Both H, Hansen PK, Hendriksen C, Kreiner S, Torp-Pedersen K. Incidence and prevalence of ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in the County of Copenhagen, 1962 to 1978. Gastroenterology. 1982;83:563–568.

Durand MT, Becari C, de Oliveira M, et al. Pyridostigmine restores cardiac autonomic balance after small myocardial infarction in mice. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104476.

de La Fuente RN, Rodrigues B, Moraes-Silva IC, et al. Cholinergic stimulation with pyridostigmine improves autonomic function in infarcted rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2013;40:610–616.

Kakinuma Y, Tsuda M, Okazaki K, et al. Heart-specific overexpression of choline acetyltransferase gene protects murine heart against ischemia through hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-related defense mechanisms. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2:e004887.

Wecht JM, Cirnigliaro CM, Azarelo F, Bauman WA, Kirshblum SC. Orthostatic responses to anticholinesterase inhibition in spinal cord injury. Clin Auton Res. 2015;25:179–187.

Bharucha AE, Low P, Camilleri M, et al. A randomised controlled study of the effect of cholinesterase inhibition on colon function in patients with diabetes mellitus and constipation. Gut. 2013;62:708–715.

Costantini TW, Krzyzaniak M, Cheadle GA, et al. Targeting alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor in the enteric nervous system: a cholinergic agonist prevents gut barrier failure after severe burn injury. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:478–486.

Sopori M. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:372–377.

Wang H, Yu M, Ochani M, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha7 subunit is an essential regulator of inflammation. Nature. 2003;421:384–388.

Lunney PC, Leong RW. Review article: ulcerative colitis, smoking and nicotine therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2012;36:997–1008.

Razani-Boroujerdi S, Boyd RT, Davila-Garcia MI, et al. T cells express alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunits that require a functional TCR and leukocyte-specific protein tyrosine kinase for nicotine-induced Ca2+ response. J Immunol. 2007;179:2889–2898.

Fu XW, Wood K, Spindel ER. Prenatal nicotine exposure increases GABA signaling and mucin expression in airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44:222–229.

Vassallo R, Tamada K, Lau JS, Kroening PR, Chen L. Cigarette smoke extract suppresses human dendritic cell function leading to preferential induction of Th-2 priming. J Immunol. 2005;175:2684–2691.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ruben Castro and Shah Hussain for help with staining and imaging of the tissue sections. This work was supported by a grant from CDMRP (GW150022) and NIH (RO1 HL 125000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, S.P., Chand, H.S., Banerjee, S. et al. Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitor Pyridostigmine Bromide Attenuates Gut Pathology and Bacterial Dysbiosis in a Murine Model of Ulcerative Colitis. Dig Dis Sci 65, 141–149 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05838-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05838-6