Abstract

Purpose

The mechanisms driving the physical activity–breast cancer association are unclear. Exercise both increases reactive oxygen species production, which may transform normal epithelium to a malignant phenotype, and enhances antioxidant capacity, which could protect against subsequent oxidative insult. Given the paradoxical effects of physical activity, the oxidative stress pathway is of interest. Genetic variation in CAT or antioxidant-related polymorphisms may mediate the physical activity–breast cancer association.

Methods

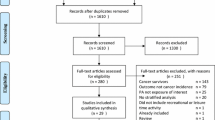

We investigated the main and joint effects of three previously unreported polymorphisms in CAT on breast cancer risk. We also estimated interactions between recreational physical activity (RPA) and 13 polymorphisms in oxidative stress-related genes. Data were from the Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project, with interview and biomarker data available on 1,053 cases and 1,102 controls.

Results

Women with ≥1 variant allele in CAT rs4756146 had a 23 % reduced risk of postmenopausal breast cancer compared with women with the common TT genotype (OR = 0.77; 95 % CI = 0.59–0.99). We observed two statistical interactions between RPA and genes in the antioxidant pathway (p = 0.043 and 0.006 for CAT and GSTP1, respectively). Highly active women harboring variant alleles in CAT rs1001179 were at increased risk of breast cancer compared with women with the common CC genotype (OR = 1.61; 95 % CI, 1.06–2.45). Risk reductions were observed among moderately active women carrying variant alleles in GSTP1 compared with women homozygous for the major allele (OR = 0.56; 95 % CI, 0.38–0.84).

Conclusions

Breast cancer risk may be jointly influenced by RPA and genes involved in the antioxidant pathway, but our findings require confirmation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ambrosone CB (2000) Oxidants and antioxidants in breast cancer. Antioxid Redox Signal 2:903–917

Kang DH (2002) Oxidative stress, DNA damage, and breast cancer. AACN Clin Issues 13:540–549

Behrend L, Henderson G, Zwacka RM (2003) Reactive oxygen species in oncogenic transformation. Biochem Soc Trans 31:1441–1444. doi:10.1042/

Caporaso N (2003) The molecular epidemiology of oxidative damage to DNA and cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 95:1263–1265

Halliwell B (2000) The antioxidant paradox. Lancet 355:1179–1180. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02075-4

Martin KR, Barrett JC (2002) Reactive oxygen species as double-edged swords in cellular processes: low-dose cell signaling versus high-dose toxicity. Hum Exp Toxicol 21:71–75

Cooke MS, Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M et al (2003) Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J 17:1195–1214. doi:10.1096/fj.02-0752rev

Klaunig JE, Kamendulis LM (2004) The role of oxidative stress in carcinogenesis. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 44:239–267. doi:10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121851

Tas F, Hansel H, Belce A et al (2005) Oxidative stress in breast cancer. Med Oncol 22:11–15. doi:10.1385/MO:22:1:011

Forsberg L, Lyrenas L, de Faire U et al (2001) A common functional C-T substitution polymorphism in the promoter region of the human catalase gene influences transcription factor binding, reporter gene transcription and is correlated to blood catalase levels. Free Radic Biol Med 30:500–505

Ahn J, Gammon MD, Santella RM et al (2005) Associations between breast cancer risk and the catalase genotype, fruit and vegetable consumption, and supplement use. Am J Epidemiol 162:943–952. doi:10.1093/aje/kwi306

Nadif R, Mintz M, Jedlicka A et al (2005) Association of CAT polymorphisms with catalase activity and exposure to environmental oxidative stimuli. Free Radic Res 39:1345–1350. doi:10.1080/10715760500306711

Ahn J, Nowell S, McCann SE et al (2006) Associations between catalase phenotype and genotype: modification by epidemiologic factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 15:1217–1222. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0104

Bastaki M, Huen K, Manzanillo P et al (2006) Genotype-activity relationship for Mn-superoxide dismutase, glutathione peroxidase 1 and catalase in humans. Pharmacogenet Genomics 16:279–286. doi:10.1097/01.fpc.0000199498.08725.9c

Quick SK, Shields PG, Nie J et al (2008) Effect modification by catalase genotype suggests a role for oxidative stress in the association of hormone replacement therapy with postmenopausal breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 17:1082–1087. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2755

Li Y, Ambrosone CB, McCullough MJ et al (2009) Oxidative stress-related genotypes, fruit and vegetable consumption and breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 30:777–784. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgp053

Friedenreich CM, Cust AE (2008) Physical activity and breast cancer risk: impact of timing, type and dose of activity and population subgroup effects. Br J Sports Med 42:636–647. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.029132

Rundle A (2005) Molecular epidemiology of physical activity and cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:227–236

Neilson HK, Friedenreich CM, Brockton NT et al (2009) Physical activity and postmenopausal breast cancer: proposed biologic mechanisms and areas for future research. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 18:11–27. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0756

McTiernan A (2008) Mechanisms linking physical activity with cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 8:205–211. doi:10.1038/nrc2325

Gammon MD, Neugut AI, Santella RM et al (2002) The Long Island Breast Cancer Study Project: description of a multi-institutional collaboration to identify environmental risk factors for breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 74:235–254

Zongli X, Taylor J (2009) SNPinfo: Integrating GWAS and candidate gene information into Functional SNP Selection for Genetic Association Studies

International HapMap Consortium (2003) The International HapMap project. Nature 426:789–796. doi:10.1038/nature02168

Terry MB, Gammon MD, Zhang FF et al (2004) Polymorphism in the DNA repair gene XPD, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon-DNA adducts, cigarette smoking, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13:2053–2058

Gaudet MM, Bensen JT, Schroeder J et al (2006) Catechol-O-methyltransferase haplotypes and breast cancer among women on Long Island, New York. Breast Cancer Res Treat 99:235–240. doi:10.1007/s10549-006-9205-0

Ahn J, Gammon MD, Santella RM et al (2005) No association between glutathione peroxidase Pro198Leu polymorphism and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 14:2459–2461. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0459

Ahn J, Gammon MD, Santella RM et al (2006) Effects of glutathione S-transferase A1 (GSTA1) genotype and potential modifiers on breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 27:1876–1882. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgl038

Steck SE, Gaudet MM, Britton JA et al (2007) Interactions among GSTM1, GSTT1 and GSTP1 polymorphisms, cruciferous vegetable intake and breast cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 28:1954–1959. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgm141

Gaudet MM, Gammon MD, Santella RM et al (2005) MnSOD Val-9Ala genotype, pro- and anti-oxidant environmental modifiers, and breast cancer among women on Long Island, New York. Cancer Causes Control 16:1225–1234. doi:10.1007/s10552-005-0375-6

Ahn J, Gammon MD, Santella RM et al (2004) Myeloperoxidase genotype, fruit and vegetable consumption, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Res 64:7634–7639. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1843

Bernstein L, Henderson BE, Hanisch R et al (1994) Physical exercise and reduced risk of breast cancer in young women. J Natl Cancer Inst 86:1403–1408

McCullough LE, Eng SM, Bradshaw PT et al (2012) Fat or fit: the joint effects of physical activity, weight gain, and body size on breast cancer risk. Cancer. doi:10.1002/cncr.27433

Ziegler A, Konig I (2006) A statistical approach to genetic epidemiology. Wiley, New York

Kleinbaum DG, Klein M (2002) Logistic Regression: A Self-Learning Text, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Greenland S, Brumback B (2002) An overview of relations among causal modelling methods. Int J Epidemiol 31:1030–1037

Greenland S (1989) Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. Am J Public Health 79:340–349

Breslow NE, Day NE (1980) Statistical methods in cancer research. volume i—the analysis of case-control studies. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon

Yang XR, Chang-Claude J, Goode EL et al (2011) Associations of breast cancer risk factors with tumor subtypes: a pooled analysis from the Breast Cancer Association Consortium studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 103:250–263. doi:10.1093/jnci/djq526

Assmann SF, Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S et al (1996) Confidence intervals for measures of interaction. Epidemiology 7:286–290

Rothman K, Greenland S (1998) Modern Epidemiology, 2nd edn. Maple Press, Philadelphia

Kanter MM (1994) Free radicals, exercise, and antioxidant supplementation. Int J Sport Nutr 4:205–220

Ayres S, Baer J, Subbiah MT (1998) Exercised-induced increase in lipid peroxidation parameters in amenorrheic female athletes. Fertil Steril 69:73–77

Clarkson PM, Thompson HS (2000) Antioxidants: what role do they play in physical activity and health? Am J Clin Nutr 72:637S–646S

Singh VN (1992) A current perspective on nutrition and exercise. J Nutr 122:760–765

Guerra A, Rego C, Castro E et al (2000) LDL peroxidation in adolescent female gymnasts. Rev Port Cardiol 19:1129–1140

Guerra A, Rego C, Laires MJ et al (2001) Lipid profile and redox status in high performance rhythmic female teenagers gymnasts. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 41:505–512

Vani M, Reddy GP, Reddy GR et al (1990) Glutathione-S-transferase, superoxide dismutase, xanthine oxidase, catalase, glutathione peroxidase and lipid peroxidation in the liver of exercised rats. Biochem Int 21:17–26

Evelo CT, Palmen NG, Artur Y et al (1992) Changes in blood glutathione concentrations, and in erythrocyte glutathione reductase and glutathione S-transferase activity after running training and after participation in contests. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 64:354–358

Miyazaki H, Oh-ishi S, Ookawara T et al (2001) Strenuous endurance training in humans reduces oxidative stress following exhausting exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol 84:1–6

Powers SK, Ji LL, Leeuwenburgh C (1999) Exercise training-induced alterations in skeletal muscle antioxidant capacity: a brief review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 31:987–997

Radak Z, Chung HY, Goto S (2008) Systemic adaptation to oxidative challenge induced by regular exercise. Free Radic Biol Med 44:153–159. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.029

Hoffman-Goetz L, Pervaiz N, Guan J (2009) Voluntary exercise training in mice increases the expression of antioxidant enzymes and decreases the expression of TNF-alpha in intestinal lymphocytes. Brain Behav Immun 23:498–506. doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.015

Siu PM, Pei XM, Teng BT et al (2011) Habitual exercise increases resistance of lymphocytes to oxidant-induced DNA damage by upregulating expression of antioxidant and DNA repairing enzymes. Exp Physiol 96:889–906. doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2011.058396

Hu X, Ji X, Srivastava SK et al (1997) Mechanism of differential catalytic efficiency of two polymorphic forms of human glutathione S-transferase P1–1 in the glutathione conjugation of carcinogenic diol epoxide of chrysene. Arch Biochem Biophys 345:32–38. doi:10.1006/abbi.1997.0269

Sundberg K, Johansson AS, Stenberg G et al (1998) Differences in the catalytic efficiencies of allelic variants of glutathione transferase P1–1 towards carcinogenic diol epoxides of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Carcinogenesis 19:433–436

Mao GE, Morris G, Lu QY et al (2004) Glutathione S-transferase P1 Ile105Val polymorphism, cigarette smoking and prostate cancer. Cancer Detect Prev 28:368–374. doi:10.1016/j.cdp.2004.07.003

Schaid DJ, Jacobsen SJ (1999) Biased tests of association: comparisons of allele frequencies when departing from Hardy-Weinberg proportions. Am J Epidemiol 149:706–711

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Environmental Health and Sciences (Grant nos. UO1CA/ES66572, P30ES009089, and P30ES10126), the Department of Defense (Grant no. BC093608), and the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Breast Cancer SPORE (Grant no. P50CA058223). Drs. Santella and Ambrosone are recipients of funding from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McCullough, L.E., Santella, R.M., Cleveland, R.J. et al. Polymorphisms in oxidative stress genes, physical activity, and breast cancer risk. Cancer Causes Control 23, 1949–1958 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-0072-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-012-0072-1