Abstract

Concurrent sexual partnerships (i.e., relationships that overlap in time) contribute to higher HIV acquisition risk. Social capital, defined as resources and connections available to individuals is hypothesized to reduce sexual HIV risk behavior, including sexual concurrency. Additionally, we do not know whether any association between social capital and sexual concurrency is moderated by gender. Multivariable logistic regression tested the association between social capital and sexual concurrency and effect modification by gender. Among 1445 African Americans presenting for care at an urban STI clinic in Jackson, Mississippi, mean social capital was 2.85 (range 1–5), mean age was 25 (SD = 6), and 62% were women. Sexual concurrency in the current year was lower for women compared to men (45% vs. 55%, χ2(df = 1) = 11.07, p = .001). Higher social capital was associated with lower adjusted odds of sexual concurrency for women compared to men (adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] = 0.62 (95% CI 0.39–0.97), p = 0.034), controlling for sociodemographic and psychosocial covariates. Interventions that add social capital components may be important for lowering sexual risk among African Americans in Mississippi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

African Americans remain the racial group with the highest prevalence and incidence of HIV infection in the United States (U.S), especially in the south [1]. The southern region, where more than 50% of African Americans reside, is the region with the highest lifetime HIV risk [2]. Jackson, Mississippi (MS), the setting for this study, ranks 6th for new HIV diagnosis and 1st for late HIV diagnosis (i.e., HIV concurrently diagnosed with AIDS) among 95 metropolitan areas in the US [3]. Disparities by race and gender are pronounced. Within Jackson, MS, in 2017, the rate of infection per 100,000 was 62 for African American men compared to 7 for white men, 15 for African American women, and 2 for white women [4].

Racial and ethnic disparities in HIV are not wholly explained by differences in sexual or drug use risk behaviors but rather, attributed to other factors such as delays in testing and accessing HIV prevention, differences in sociodemographic factors of sexual partners (e.g., age and gender), higher HIV prevalence in sexual networks, assortative sexual mixing, and concurrent sexual partnerships [5,6,7,8]. Concurrent sexual partnerships (i.e., sexual relationships that overlap in time), is one type of sexual network characteristic that can raise HIV acquisition risks [9] and the magnitude of risk is hypothesized to vary by local epidemiologic context [10]. In some American cities with a high proportion of African Americans, structural factors, including incarceration and poor economic prospects increase the flow of people that leave while also creating imbalances in male to female sex ratios among those who remain [11, 12]. Jackson, MS is the 3rd highest racially segregated city in the U.S [13], and the overall population of MS has been declining, primarily due to domestic outmigration [14].

Previous studies have identified high rates of concurrent sexual partnerships in Mississippi [15, 16]. Therefore, understanding risk factors for concurrent sexual partnerships may inform interventions that reduce self-reported HIV risk behaviors.

Social capital is a multidimensional construct that is operationalized typically within two broad approaches: cognitive and structural [17]. The construct is more frequently conceptualized as a property of the community/neighborhood [18], while others view it as a property of individuals or networks [19]. The cognitive approach, also sometimes referred to as social cohesion, emphasizes perceptions of trust, sharing, and reciprocity. In contrast, the structural approach emphasizes social networks, civic engagement, participation in organiztions, social control, and other group-level properties. There is some debate whether social cohesion is an antecedent to social capital [20]. Others find utility in seeing both as one broad construct [18], encompassing multiple forms, and connected to social embeddedness [21]. Thus, we define social capital broadly as collective resources available to individuals based on social connections [18, 19]. In this study, perceived neighborhood social capital was operationalized at the individual level. This means that individuals reported their perceptions, but the data were not aggregated to the neighborhood level because geographic identifiers were not available. Social capital has been put forth in many theoretical models as a determinant that influences self-reported HIV risk and transmission [22, 23].

Although seen as a broad concept, cognitive-based indicators often used to operationalize social capital in health-related studies have varied tremendously, including in studying HIV/AIDS [24,25,26]. Some mechanisms are related to the acquisition of social capital at the individual level as well as facilitating links to health behaviors. Some mechanisms hypothesized to link social capital at the individual level to health behaviors include diffusion of information and psychosocial processes that improve coping, self-esteem, and respect. Those mechanisms either have direct effects or buffer the effects of other determinants such as poverty, depression, and excessive alcohol use [18, 27,28,29]. Behavioral and psychological factors such as excessive alcohol use, depression, and self-reported HIV risk may also vary by gender and thus are important to examine as main variables rather than confounders. African American women, compared to men, have lower rates of drinking and alcohol abuse [30]. While depressive symptoms may be manifested and thus diagnosed differently among African Americans [31], the diagnosed prevalence is higher among women compared to men [32]. Finally, although self-reported HIV risk is complex in that it depends on relationship status and other contextual factors such as HIV prevalence [33], African American women compared to men identify more frequently with lower self-reported HIV risk [34, 35].

There is compelling evidence that social capital is associated with HIV-related risk and protective factors such as condom use, number of sexual partners, and HIV testing [26]. It is unclear, however, whether social capital is associated with sexual concurrency, which is the first question we investigate in this study. Broadly, mechanisms hypothesized to link social capital to lower self-reported HIV risk include higher access to material resources, which can leverage negotiating safer sexual practices such as using condoms and reducing the number of overlapping sexual partners [36, 37]. It is also possible that higher social capital could increase HIV transmission risk if higher perceived trust in one’s community and residens facilitates greater opportunities for casual sexual relationships with multiple people [38].

Based on theory and empirical evidence, it is plausible that gender may modify the relationship between social capital at the individual level and self-reported HIV risk behaviors, such as sexual concurrency, which is the second question we investigate in this study. The theory of gender and power posits that there are gendered relationships between men and women [39] that could influence risk. The division of labor can produce gender differences in self-reported HIV risk, particularly in the south, because women are posited to more heavily rely on their social networks for support [40]. For instance, African American women in Mississippi earn fifty-five cents for every dollar earned by a white man [41] and the average cost of child-care exceeds 20% of women’s median annual earnings. Women compared to men also tend to have higher levels of family responsibilities (e.g., raising children) and consequently may have limited time to engage in social activities that accumulate social capital as well as financial resources [42].

There are also gendered relationships within cultural norms that structure women’s perceptions of expectations of sexual roles and intimate relationships as well as how society expects women to behave [43, 44]. Also, individual and societal perceptions and expectations of sexual roles, structural conditions such as incarceration differentially affect social capital levels between African American men and women. High incarceration rates of African American men in the U.S [45]. shrink the pool of potential partners [46] and result in higher female-to-male sex ratios. These conditions create higher likelihoods that African American women end up or stay in non-monogamous and overlapping sexual relationships with their male partners [40]. Other work has shown that prior incarceration is associated with an increased rate of lifetime sexual partnerships for men [47].

There is compelling empirical evidence of gender differences in the association between social capital and HIV diagnosis and sexual risk behavior [48]. However, the evidence is mixed about the directions of associations and no studies have examined sexual concurrency. One study in Eastern Zimbabwe showed that social capital was associated with lower HIV incidence, yet the magnitude of the association was larger for women compared to men. Women were able to leverage their social capital to adopt safer sexual practices [49]. One study among adults in South Africa found that cognitive social capital (e.g., perceived reciprocity and support) was significantly associated with higher odds of consistent condom use and condom use at last sex for men but not for women [50]. That study did not provide sufficient explanations for the gendered patterns of those associations.

Understanding the role of social capital in having concurrent sexual partnerships (hereafter, sexual concurrency), as one HIV acquisition risk factor, may be necessary to reduce racial disparities, especially among women, in the Mississippi and across the south.

In the present study, we examined the association between social capital and sexual concurrency and then tested whether gender modified that association. As a second objective, we tested the hypothesis that psychosocial and behavioral factors: excessive alcohol use, depressive symptoms, and self-reported HIV risk attenuate any gender differences found.

Methods

Study Design and Sample

Data were drawn from a cross-sectional study of 1542 individuals who presented for care at a publicly funded STI clinic in Jackson, Mississippi. Recruitment and data collection procedures have been previously described Nunn et al. [51]. Briefly, individuals presenting for care between January and June 2011 were offered participation in the study; 93% of individuals accepted. Individuals were eligible to participate if they met the following criteria: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) presenting for STI and HIV screening, (3) willing to complete a 30 min computerized behavioral survey, and (4) spoke English. Participants did not receive compensation for their participation, and all provided informed consent before completing the self-administered computerized survey. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the Mississippi State Department of Health, and The Miriam Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island. We restricted this sample to African Americans (n = 1445).

Measures

Social Capital

The computerized survey solicited information regarding sociodemographic characteristics, substance use, sexual behavior history, access to medical care, as well as structural factors. A social cohesion-based approach [18] was used to operationalize perceived neighborhood social capital, which was assessed using a validated scale [52]. Participants were asked to rate the following statements on a scale of 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree): (1) “people around here are willing to help their neighbors”, (2) “people in my neighborhood can be trusted”, (3) “people in my neighborhood generally get along with each other”, (4) “people in my neighborhood generally share the same values”, and (5) “I live in a close-knit neighborhood”. Consistent with prior work [52], a z-scored summary index variable with mean of 0 and SD of 1 was created, rather than analyze individual items. This index variable was created through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) confirmatory factor analysis techniques [53] using STATA v14.1 software [54]. Although the questions ask about their neighborhood and neighbors, the data are all at the individual level.

Concurrency

To determine sexual concurrency, the following information was solicited from participants: “Please list your three most recent sexual partners in the past 6 months.” Sex, in the context of the survey, was defined as vaginal, anal or oral intercourse. Patients were then asked the following binary (yes/no) question: “During the time period you were having sex with PARTNER INITIALS, did you also have other sexual partners?” If participants responded “yes”, they were coded as engaged in a concurrent partnership for either the past or current year.

Covariates

In our analyses, we included the following socioeconomic variables: age, gender (men vs. women), sexual orientation (heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual), marital status (single, married or in a common-law union, divorced or other), highest level of education obtained (high school or less, some college, college degree or higher), monthly gross income (< $500, $501–$1500, $1501–$3000, > $3000), employment (full or part-time, unemployed and looking for work, unemployed and not looking for work), and receipt of public assistance (yes vs. no).

Psychosocial and Behavioral Variables

In addition, to examine whether psychosocial and behavioral factors can attenuate gender differences in social capital and sexual concurrency, the following variables were examined: excessive alcohol use operationalized through the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)-C cutoff (on a scale of 1–12 based on 10 AUDIT-C questions where ≥ 4 for men or ≥ 3 for women was considered hazardous use), self-reported depression (In the past 30 days, have you felt downhearted or depressed for more than a day? yes vs. no), and self-reported HIV risk (How would you rate your own HIV risk? not at risk, low, moderate, high).

Statistical Analyses

We first examined the distributional properties of each variable. To assess the relationship between social capital and sexual concurrency in our analytic sample, we used multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, gender, sexual orientation, marital status, education, income, employment, and public assistance (Model 1).

In order to examine effect modification (hereafter, interaction) between gender and continuously coded social capital in our sample, we created an interaction term between gender*social capital and entered it into the model, adjusting for covariates. We tested for differences on the multiplicative scale between men and women using the Adjusted Wald Test and confirmed the results by performing interaction contrasts of gender differences on the probability scale (margins), and on the additive scale since interactions may be present on one scale but not another [55, 56]. We then calculated the relative excess risk due to the interaction (RERI) and test the significance of the RERI using STATA code provided by VanderWeele and Knol 2014 [57]. Social capital was coded into a binary variable to calculate the RERI since values have to be chosen even from continuously scored variables. We created a binary variable (− 2/0 classified as low and anything higher classified as high).

To accomplish our secondary objective, whether psychosocial and behavioral factors can attenuate gender differences in social capital and concurrency, an additional model was created (Model 2) in which we subsequently adjusted for excessive alcohol use, self-reported depression, and self-reported HIV risk. To improve specification of the model, we entered an interaction term between AUDIT-C hazardous alcohol use and self-reported HIV risk because prior work showed strong causal associations in the context of sexual risk [58]. All variables that were significant at p < 0.10 in bivariable analyses were included in both models. We reported two-sided p-values. We assessed the significance of the interactions at p < 0.05. When significant interactions were found, we plot the results using the margins command based on the adjusted Model 2.

Results

Table 1 shows the sociodemographic characteristics of the analytic sample. The average age was 24.7 years, approximately 61.5% of the participants were men, single (87.3%) and heterosexual (89.6%). Over forty percent (42%) of the sample had a high school or less education and a little over half (53.2%) of the participants reported being employed full or part-time with almost sixty percent (58.7%) receiving public assistance. A total of 482 participants (34.8%) self-reported depression. About 48% met criteria for hazardous alcohol use, while 48.8% had some self-reported HIV risk. Fifty-five percent of men and 45% of women reported having concurrent sexual relationships in the current year. The average social capital score for the whole analytic sample was 2.84 (with 1 being the lowest score and 5 being the highest), and there were no significant differences in mean social capital between men and women (results not displayed).

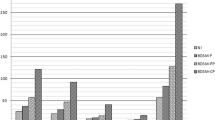

Table 2 shows the multivariable logistic regression models for sexual concurrency in the current year. In initial main effect models, gender but not social capital was significant (result not displayed). From the interaction models, we found that gender significantly modified the association between social capital and sexual concurrency, while adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (Model 1, χ2 (df = 1) = 5.02, p = 0.025). Specifically, higher social capital was associated with lower odds of sexual concurrency among women [aOR] = 0.60 (95% CI 0.38, 0.94), p = 0.025 compared to men [aOR] = 1.66 (95% CI 1.06, 2.59), p = 0.025. Model 2 contains the addition of psychosocial factors (depressive symptoms and the interaction between AUDIT-c hazardous alcohol use * self-reported HIV risk) in the multivariable model for sexual concurrency in the current year. The gender by social capital effect modification remained significant (Model 1, χ2 (df = 1) = 4.45, p = 0.035). Addition of these variables did not meaningfully alter the magnitude of associations for women [aOR] = 0.62 (95% CI 0.39, 0.97), p = 0.035 or men [aOR] = 1.62 (95% CI 1.03, 2.53), p = 0.035. Men’s risk was still about 60% higher compared to women at mean levels of social capital. The graphical illustration in Fig. 1 shows a diverging direction of trends and different magnitudes by gender, which provides compelling evidence that men’s risk of being in a concurrent sexual relationship is higher as social capital increased. Table 3 contains results of analyses from sexual concurrency in the past year. The pattern of results and the interaction plot (not presented) were very similar to those in the current year and so are not presented. The previous effect modification coefficients were presented on the multiplicative scale for men and women. The relative excess risk due to the interaction (RERI), which is effect modification on the additive scale, was − 0.56 95% CI (− 1.09, − 0.03), p = 0.08. This results suggests that if social capital was a scarce resource, then social capital interventions for sexual concurrency might have a greater public health benefit if targeted towards men, and this interpretation was based on us coding men 0 and women 1 in the statistical models.

Discussion

Sexual concurrency remains a key risk factor that contributes to high HIV incidence among African Americans, particularly in the south, and more likely to have an adverse impact on women. Social capital has been associated with other self-reported HIV risk behaviors such condom use. However, no prior studies examined its association with sexual concurrency. Therefore, we examined whether social capital was associated with sexual concurrency, and whether gender moderated any association found. Our second question was informed by the theory of gender and power and empirical work on the topic [40, 49, 50].

We found strong statistical evidence for divergent slopes and magnitude in the association between social capital and sexual concurrency, therefore we conclude effect modification based on gender. Specifically, as social capital increased, the predicted probability that one would have a concurrent sexual partner was increasing for men but decreasing for women.

This gender effect modification pattern could potentially be explained by a few possibilities. First, we speculate that social capital is both accumulated and used differentially by men and women. For instance, one study from East Zimbabwe that examined gender, and HIV incidence in association with social capital through indicators of community group membership participation [58, 59]. The authors found that social capital was associated with lower HIV incidence for women compared to men and that gender difference was primarily driven through women’s increased self-efficacy to persuade their partners to practice safer sex [58, 59]. In our study, social capital was measured via a social cohesion approach (i.e., including indicators such as perceived trust and belonging to community). From the social cohesion perspective, it is possible that women with higher social cohesion are protected from some social and structural factors associated with sexual concurrency, such as economic dependence on partners [60]. Women in this possible scenario could be engaged in social networks with positive norms that discourage specific behavioral characteristics [61] and may become more trusting of their community and in turn, the partners found in their community. Women may also feel more able to seek economic help from the community rather than through overlapping sexual partners.

Second, it is possible that gender differences may be a function of where social capital was obtained. In the East Zimbabwe study, men were more likely to participate in sports clubs and political associations, whereas women frequently participated in church groups and events that discussed AIDS [58]. In Jackson, MS, how social capital is generated for men and women may also be different and possibly depend on one’s neighborhood of residence. Social capital has often been conceptualized at the neighborhood level and neighborhood social cohesion has been associated with condom use [62], although ther are no studies linking it to sexual concurrency.

Third, gender differences in the association could be differential participation in social capital generating activities. It is well documented that African American women have higher levels of religious participation compared to men [63] and that the Black Church (i.e., religious and faith congregations with predominantly black parishioners) tend to be more conservative regarding sexual behaviors [64]. Therefore, it is possible that religious involvement may be on a causal pathway through which social capital influenced lower concurrency among women by discouraging risky sexual behaviors such as sexual concurrency [65].

Fourth, divergent gender patterns could possibly be explained by the economic and psychosocial coping opportunities that social capital provides, which may differ for men and women. Some posit that for men, having multiple overlapping sexual partnerships may be a strategy for survival or primary source of social support and capital [66]. Prior research on sexual concurrency among African American men in Philadelphia found that men relied on concurrent sexual partners for food, shelter, and economic support [67]. However, there is another side not often discussed, which are that some men may be seeking psychosocial and emotional support to buffer against hardships and constant threat associated with being a black male in America. This point is well illustrated in barbershop intervention study that assessed HIV prevention among heterosexually-identified men [68]. Men reported in qualitative interviews that multiple overlapping sexual partners provided emptional support and security, as demonstrated by one participant who said the women helped him cope with abandonment he experienced earlier in life [68].

For women, the reasons may be different. One study in Jackson, MS found that women were more likely to engage in sexual concurrency if they had one or more partners with a history of incarceration [51]. One study that used a Black feminist framework analyzed qualitative data posited that some African American women may engage in concurrent sexual partnership as a form of resistance to male-dominated sexual norms within society [69]. However, although autonomy may be important for self-esteem and resilience, studies have shown low or inconsistent use of preventive self-reported HIV risk behaviors among women who engaged in those relationships, which is problematic for HIV prevention [69, 70].

Societal expectations could potentially account for these gender differences we observed. It is possible that women may be socially forced to comply with gender norms of having one partner [71]. Gender norms, when intersecting with race relations in Jackson, MS, have had a lasting negative impact on African American women in this sociocultural conservative region of the country [72]. At the same time, male-dominated gender relations may also make it easier for men to engage in double standards so that the more social capital they have, the more access and opportunity to engage in extramarital affairs and concurrent sexual relationships [73].

A secondary objective of our study was to identify whether psychosocial factors could attenuate any gender differences observed. Previous work by Gregson et al. [49] found that men were more likely than women to participate in events that involved alcohol use. Additionally, excessive alcohol use and self-reported depression may indicate social problems for which seeking social support (whether through sexual partnerships or otherwise) may be a coping mechanism [74, 75]. Adjusting for these factors did not materially alter the degree to which gender modified the relationship between social capital and sexual concurrency in our study.

Our study is perhaps the first published work internationally or domestically to examine the association between social capital and sexual concurrency and demonstrate effect modification by gender. We build upon prior work that highlighted the socio-contextual determinants of self-reported HIV risk among African Americans concerning sexual concurrency as a primary driver [76]. Our findings, if confirmed in replicate studies with other populations, could have major implications for HIV-behavioral and biomedical interventions. Stakeholders will then have to decide who to target for interventions. Based on the RERI coefficient < 0, the statistical model would suggest a greater public health impact by targeting men.

Statistics, though need not be the drivig factor. One could easily argue for intervening among women to keep sexual concurrency low among them by adding social capital components [65] to existing and successful evidence-based interventions to reduce HIV risk among African-American women (e.g., Healthy Love) [77]. In that intervention, one could potentially add components to the module that show women how to identify resources of social capital within their networks and leverage that for strength in negotiating relationships and other sexual behaviors [78]. In his 2015 movie Chi-Raq, Spike Lee illustrates how black women gathered together and withheld sex from their husbands [79], which was their intervention to reduce violence in their neighborhood. Although the movie was fiction, women demonstrated several components of social capital [80] such as strong connections to their neighborhoods, which led them to take action in response to a public health problem that threatned people they love.

For men, interventions may be more complex because the HIV epidemiologic profile among black men is patterned by transmission status. Male to male sexual contact among black men accounts for 80% of new HIV diagnosis compared to 14% from heterosexual contact. Therefore, the implications for sexual concurrency will depend on which subgroup of men are targeted. For example, the Barbershop Talk with Brothers (BTWB) targeted heterosexually identified men and is one successful intervention that showed a 60% increase in likelihood of using condoms during sex, among the intervention compared to control group [81]. Earlier work from that same sample of men identified sexual concurrency as an issue, though it was not an end point of the study [68].

Social cohesion and capital are group level properties and so its possible for one to conceptualize barbershops as “neighborhoods” since each shop has a unique culture, social norms and geographic boundaries. Barbershops are an ideal setting for social cohesion generation among black men because there is often perceived trust and belongingness. Therefore, one can potentially add modules to BTWB (and similar interventions) to discuss the sexual, HIV-related and other societal implications of having multiple overlapping sexual partners.

For black men who have sex with men (MSM), there are a number of interventions with varying success, which have foused mainly on sexual risk reduction strategies including: consistent condom use and timely HIV testing, dealing with homophobia, sexual identity, and partner selection, but none on systematically addressed concurrent sexual partnerships [82]. Nevertheless, there are interventions such as Many Men Many Voices (3MV) that are based in neighborhoods and developed and delivered by community-based organziations that serve black MSM [83]. One randomized trial study evaluating 3MV found a 25% greater reduction number of casual sexual partners, among those in the intervention compared to comparison group [83]. Future interventions could leverage prior social capital and HIV-related behavior research among black MSM in the U.S [84,85,86]. and internationally [87] to develop modules that are consistent with social cohesion indicators.

Our results are subject to several limitations. This sample was drawn from an urban STI clinic with individuals at particularly high risk; thus our findings may not generalize to other African American groups with more variable risk. Our data were from an observational cross-sectional sample, so we cannot make causal inference statements about the relationship between social capital and sexual concurrency. The social capital measures in these data were limited to social cohesion indicators and at the individual level. We did not collect the residential address information from participants, nor did we ask about other social capital indicators. There are alternative and numerous conceptualizations of social capital beyond cognitive measures (e.g., informal social control and civic participation) [17, 26] that may be important for sexual concurrency. Social capital has also been frequently conceived as a property of neighborhoods. Studies that examine different measures and at the neighborhood level may provide further insight into how men and women interact with their community and any subsequent impact on sexual concurrency. Researchers should select those measures and units of analysis informed by specific theories about relationships between social capital and behaviors they study [17, 88].

There are multiple definitions of sexual concurrency (e.g., UNAIDS version, which additionally asks about the intention to have sex again with the partner). We analyzed only self-reported concurrency because of the larger sample of non-missing data and previous work indicating (1) high overlap across definitions, and (2) no significant differences in the sociodemographic correlates of concurrency based on either definition [51]. Self-reported concurrency measures may be influenced social desirability bias that is gendered. Men tend to overreport sexual partners, so the gender differences we found may be overestimated.

Lastly, in this study, we focused on a handful of psychosocial predictors (excessive alcohol use, self-reported depression, and self-reported HIV risk) as potential explanatory mechanisms. There are other structural factors, particularly incarceration [11, 12, 47] likely to significantly explain gender differences in sexual concurrency. However, incarceration, which falls under a greater umbrella of involvement with the criminal legal system is complex because of nuances such as duration and timing of incarceration [89], frequency of arrests, involvement in jails vs prison. A topic with such depth was outside the scope of the current study.

Conclusion

African Americans compared to other racial and ethnic groups, particularly in the southern cities such as Jackson, MS continue to experience high rates of new HIV infection [4]. Racial disparities in HIV infection are driven primarily through higher HIV prevalence among sexual networks, assortative mixing among African Americans, and engaging in concurrent sexual partnerships, which increases the likelihood of HIV transmission [5, 9]. We show that for men, higher social capital was associated with higher risk of having overlapping sexual partners but lower overlapping partners for women. These findings suggest that in this area, existing behavioral interventions should consider adding social cohesion components to address HIV-related disparities for African Americans. Replicate studies in other southern cities are necessary to support these findings and identify which types of social capital components are best to use.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, volume 28: diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States and dependent areas, 2016 Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/reports/surveillance/cdc-hiv-surveillance-report-2016-vol-28.pdf. Accessed 24 Jan 2018.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States by geographic distribution Atlanta, GA: CDC; 2016 [updated November 29 2016]. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html. Accessed 13 Dec 2016.

Hess KL, Hu X, Lansky A, Mermin J, Hall HI. Lifetime risk of a diagnosis of HIV infection in the United States. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(4):238–43.

Mississippi State Department of Health. 2015 STD/HIV Epidemiologic Profile Mississippi: Department of Health, STD/HIV Office; 2017. https://www.webcitation.org/query?url=https%3A%2F%2Fmsdh.ms.gov%2Fmsdhsite%2F_static%2Fresources%2F7543.pdf&date=2018-03-15. Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Aral SO, Adimora AA, Fenton KA. Understanding and responding to disparities in HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in African Americans. Lancet. 2008;372(9635):337–40.

Messer LC, Quinlivan EB, Parnell H, Roytburd K, Adimora AA, Bowditch N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to testing, treatment entry, and engagement in care by HIV-positive women of color. AIDS Patient Care ST. 2013;27(7):398–407.

Millett GA, Peterson JL, Flores SA, Hart TA, Jeffries WL 4th, Wilson PA, et al. Comparisons of disparities and risks of HIV infection in black and other men who have sex with men in Canada, UK, and USA: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;380(9839):341–8.

Marshall BDL, Perez-Brumer AG, MacCarthy S, Mena L, Chan PA, Towey C, et al. Individual and partner-level factors associated with condom non-use among African American STI clinic attendees in the deep south: an event-level analysis. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(6):1334–422.

Garnett GP, Johnson AM. Coining a new term in epidemiology: concurrency and HIV. AIDS. 1997;11(5):681–3.

Boily M-C, Alary M, Baggaley RF. Neglected issues and hypotheses regarding the impact of sexual concurrency on HIV and sexually transmitted infections. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):304–11.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ, Martinson F, Donaldson KH, Stancil TR, Fullilove RE. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African Americans in the rural south. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14(3):155–60.

Grieb SMD, Davey-Rothwell M, Latkin CA. Concurrent sexual partnerships among urban African American high-risk women with main sex partners. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(2):323–33.

24/7 Wall St. America's most segregated cities Online: Huffingtonpost.com; 2016. https://www.webcitation.org/query?url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.huffingtonpost.com%2Fentry%2Famericas-most-segregated-cities_us_57d2c19ae4b0f831f7071b3d&date=2018-03-15. Accessed 15 Mar 2018.

Parisi M. Mississippi fact sheet: population growth, millennials, brain drain, and the economy Starkville, MS: Mississippi State University; 2018. https://www.nsparc.msstate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Mississippi-Population-Fact-Sheet.pdf. Accessed 14 Sept 2019.

Nunn A, Barnes A, Cornwall A, Rana A, Mena L. Addressing Mississippi's HIV/AIDS crisis. Lancet. 2011;378(9798):1217.

Barnes A, Nunn A, Karakala S, Sunesara I, Johnson K, Parham J, et al. State of the ART: characteristics of HIV infected patients receiving care in Mississippi (MS), USA from the medical monitoring project, 2009–2010. J Miss State Med Assoc. 2015;56(12):376–81.

Villalonga-Olives E, Kawachi I. The measurement of social capital. Gac Sanit. 2015;29(1):62–4.

Kawachi I, Berkman L. Social cohesion, social capital and health. In: Kawachi I, Berkman L, Glymour M, editors. Social epidemiology. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2014. p. 291–319.

Lin N. Building a network theory of social capital. Connections. 1999;22(1):28–51.

Carpiano RM. Toward a neighborhood resource-based theory of social capital for health: can Bourdieu and sociology help? Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):165–75.

Esser H. The two meanings of social capital. In: Castiglione D, Deth JW, Wolleb G, editors. The handbook of social capital. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008. p. 23–49.

Pellowski JA, Kalichman SC, Matthews KA, Adler N. A pandemic of the poor: social disadvantage and the US HIV epidemic. AM Psychol. 2013;68(4):197–209.

Poundstone K, Strathdee S, Celentano D. The social epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 2004;26(1):22–35.

Kawachi I, Kim D, Coutts A, Subramanian S. Reconciling the three accounts of social capital. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33:682–90.

Kawachi I, Subramanian S. Social epidemiology for the 21st century. Soc Sci Med. 2017;196:240–5.

Ransome Y, Thurber KA, Swen M, Crawford ND, German D, Dean LT. Social capital and HIV/AIDS in the United States: knowledge, gaps, & future directions. SSM-Popul Health. 2018;5:73–85.

Uphoff EP, Pickett KE, Cabieses B, Small N, Wright J. A systematic review of the relationships between social capital and socioeconomic inequalities in health: a contribution to understanding the psychosocial pathway of health inequalities. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12:54.

Wilmot NA, Dauner KN. Examination of the influence of social capital on depression in fragile families. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2017;71(3):296–302.

Weitzman ER, Chen Y-Y. Risk modifying effect of social capital on measures of heavy alcohol consumption, alcohol abuse, harms, and secondhand effects: national survey findings. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(4):303–9.

Ransome Y, Gilman SE. The role of religious involvement in black-white differences in alcohol use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77:792–801.

Walton QL, Shepard PJ. Missing the mark: cultural expressions of depressive symptoms among African-American women and men. Soc Work Ment Health. 2016;14(6):637–57.

Williams DR, González HM, Neighbors H, Nesse R, Abelson JM, Sweetman J, et al. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites: results from the National Survey of American Life. JAMA Psychiatry. 2007;64(3):305–15.

Blackstock OJ, Frew P, Bota D, Vo-Green L, Parker K, Franks J, et al. Perceptions of community HIV/STI risk among U.S women living in areas with high poverty and HIV prevalence rates. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2015;26(3):811–23.

Mays VM, Cochran SD. Issues in the perception of AIDS risk and risk reduction activities by Black and Hispanic/Latina women. Am Psychol. 1988;43(11):949–57.

Nunn A, Zaller N, Cornwall A, Mayer KH, Moore E, Dickman S, et al. Low perceived risk and high HIV prevalence among a predominantly African American population participating in Philadelphia's rapid HIV testing program. AIDS Patient Care ST. 2011;25(4):229–35.

Fonner VA, Kerrigan D, Mnisi Z, Ketende S, Kennedy CE, Baral S. Social cohesion, social participation, and HIV related risk among female sex workers in Swaziland. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1):e87527.

Campbell C, Williams B, Gilgen D. Is social capital a useful conceptual tool for exploring community level influences on HIV infection? An exploratory case study from South Africa. AIDS Care. 2002;14(1):41–544.

Holtgrave DR, Crosby RA. Social capital, poverty, and income inequality as predictors of gonorrhoea, syphilis, chlamydia and AIDS case rates in the United States. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79:62–4.

Connell R. Gender and power. Standford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1987. p. 317.

Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. Application of the theory of gender and power to examine HIV-related exposures, risk factors, and effective interventions for women. Health Educ Behav. 2000;27(5):539–65.

DuMonthier A, Childers C, Milli J. The status of black women in the United States. Washington D.C.: Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 2017.

O'Neill B, Gidengil E, editors. Gender and social capital. New York, NY: Routledge; 2005.

Lefkowitz ES, Shearer CL, Gillen MM, Espinosa-Hernandez G. How gendered attitudes relate to women’s and men’s sexual behaviors and beliefs. Sex Cult. 2014;18(4):833–46.

Lima AC, Davis TL, Hilyard K, deMarrais K, Jeffries WL, Muilenburg JL. Individual, interpersonal, and sociostructural factors influencing partner nonmonogamy acceptance among young African American women. Sex Roles. 2018;78(7):467–81.

Pettit B. Invisible men: mass incarceration and the myth of black progress. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation; 2012.

Lopoo LM, Western B. Incarceration and the formation and stability of marital unions. J Marriage Fam. 2005;67(3):721–34.

Knittel AK, Snow RC, Griffith DM, Morenoff J. Incarceration and sexual risk: examining the relationship between men’s involvement in the criminal justice system and risky sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2703–14.

Ransome Y, Galea S, Pabayo R, Kawachi I, Braunstein S, Nash D. Social capital is associated with late HIV diagnosis: an ecological analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Synd. 2016;73(2):213–21.

Gregson S, Mushati P, Grusin H, Nhamo M, Schumacher C, Skovdal M, et al. Social capital and women's reduced vulnerability to HIV infection in rural Zimbabwe. Popul Dev Rev. 2011;37(2):333–59.

Pronyk PM, Harpham T, Morison LA, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, Phetla G, et al. Is social capital associated with HIV risk in rural South Africa? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(9):1999–2010.

Nunn A, MacCarthy S, Barnett N, Rose J, Chan P, Yolken A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of concurrent sexual partnerships in a predominantly African American population in Jackson, Mississippi. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(12):2457–68.

Sampson R, Raudenbush S, Earls F. Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science. 1997;277:918–24.

Acock AC. Discovering structural equation modeling using Stata. Revised ed. College Station, TX: STATA Press; 2013. p. 306.

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14.1. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015.

VanderWeele TJ, Knol MJ. A tutorial on interaction. Epidemiol Methods. 2014;3(1):33–72.

Schwartz S. Modern epidemiologic approaches to interaction: applications to the study of genetic interactions. In: Committee on assessing interactions among social b, and genetic factors in health,, Hernandez LM, Blazer DG, editors. Genes, behavior, and the social environment: Moving beyond the nature/nurture debate. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. p. 310–37.

Knol MJ, VanderWeele TJ. Recommendations for presenting analyses of effect modification and interaction. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41(2):514–20.

Scott-Sheldon LAJ, Carey KB, Cunningham K, Johnson BT, Carey MP, Team TMR. Alcohol use predicts sexual decision-making: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the experimental literature. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(1):19–39.

Gregson S, Terceira N, Mushati P, Nyamukapa C, Campbell C. Community group participation: can it help young women to avoid HIV? an exploratory study of social capital and school education in rural Zimbabwe. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58(11):2119–322.

Nunn A, Dickman S, Cornwall A, Kwakwa H, Mayer KH, Rana A, et al. Concurrent sexual partnerships among African American women in Philadelphia: results from a qualitative study. Sex Health. 2012;9(3):288–96.

Haley DF, Wingood GM, Kramer MR, Haardörfer R, Adimora AA, Rubtsova A, et al. Associations between neighborhood characteristics, social cohesion, and perceived sex partner risk and non-monogamy among HIV-seropositive and HIV-seronegative women in the Southern U.S. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(5):1451–63.

Kerrigan D, Witt S, Glass B, Chung SE, Ellen J. Perceived neighborhood social cohesion and condom use among adolescents vulnerable to HIV/STI. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(6):723–9.

Taylor RJ, Chatters LM, Brown RK. African American religious participation. Rev Relig Res. 2014;56(4):513–38.

Stewart JM, Rogers CK, Bellinger D, Thompson K. A contextualized approach to faith-based HIV risk reduction for African American women. West J Nurs Res. 2016;38(7):819–36.

Wingood GM, Robinson LR, Braxton ND, Er DL, Conner AC, Renfro TL, et al. Comparative effectiveness of a faith-based HIV intervention for African American women: importance of enhancing religious social capital. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(12):2226–33.

Dean LT, Subramanian SV, Williams DR, Armstrong K, Zubrinsky Charles C, Kawachi I. Getting back men to undergo prostate cancer screening: the role of social capital. Am J Mens Health. 2014;9(5):385–96.

Nunn A, Dickman S, Cornwall A, Rosengard C, Kwakwa H, Kim D, et al. Social, structural and behavioral drivers of concurrent partnerships among African American men in Philadelphia. AIDS Care. 2011;23(11):1392–9.

Taylor TN, Joseph M, Henny KD, Pinto AR, Agbetor F, Camilien B, et al. Perceptions of HIV risk and explanations of sexual risk behavior offered by heterosexual black male barbershop patrons in Brooklyn, NY. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2014;7(6):1.

Campos S, Benoit E, Dunlap E. Black women with multiple sex partners: the role of sexual agency. J Black Sex Relatsh. 2016;3(2):53–74.

Lima AC, Hilyard K, Davis TL, de Marrais K, Jeffries WL, Muilenburg JL. Protective behaviours among young African American women with non-monogamous sexual partners. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20(4):442–57.

Thieme S, Siegmann KA. Coping on women’s backs: social capital-vulnerability links through a gender lens. Curr Soc. 2010;58(5):715–37.

Stockett K. The help. New York, NY: The Penguin Group; 2009. p. 418.

Stephenson R. Community-level gender equity and extramarital sexual risk-taking among married men in eight African countries. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2010;36(4):178–88.

Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. Multiple-recent sexual partnerships and alcohol use among sexually transmitted infection clinic patients, Cape Town South Africa. Sex Transm Dis. 2011;38(1):18–23.

Martínez-Hernáez A, Carceller-Maicas N, DiGiacomo SM, Ariste S. Social support and gender differences in coping with depression among emerging adults: a mixed-methods study. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2016;10(1):2.

Adimora AA, Schoenbach VJ. Social context, sexual networks, and racial disparities in rates of sexually transmitted infections. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(Supplement 1):S115–S12222.

Diallo DD, Moore TW, Ngalame PM, White LD, Herbst JH, Painter TM. Efficacy of a single-session HIV prevention intervention for Black women: a group randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):518–29.

Shushtari ZJ, Hosseini SA, Sajjadi H, Salimi Y, Latkin C, Snijders TAB. Social network and HIV risk behaviors in female sex workers: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1020.

Lee S. Chi-Raq. USA2015.

Coleman JS. Social capital in the creation of human capital. Am J Sociol. 1988;94:S95–S120.

Wilson TE, Gousse Y, Joseph MA, Browne RC, Camilien B, McFarlane D, et al. HIV prevention for black heterosexual men: the barbershop talk with brothers cluster randomized trial. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(8):1131–7.

Maulsby C, Millett G, Lindsey K, Kelley R, Johnson K, Montoya D, et al. A systematic review of HIV interventions for black men who have sex with men (MSM). BMC Public Health. 2013;13:625.

Wilton L, Herbst JH, Coury-Doniger P, Painter TM, English G, Alvarez ME, et al. Efficacy of an HIV/STI Prevention Intervention for Black Men Who Have Sex with Men: Findings from the ManyMen, ManyVoices (3MV) Project. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(3):532–44.

Frye V, Nandi V, Egan JE, Cerda M, Rundle A, Quinn JW, et al. Associations among neighborhood characteristics and sexual risk behavior among black and white MSM living in a major urban area. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(3):870–90.

Ransome Y, Zarwell MC, Robinson WT. Participation in community groups increases the likelihood of PrEP awareness: New Orleans NHBS-MSM Cycle, 2014. PLoS ONE. 2018.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213022

Zarwell MC, Robinson WT. The influence of constructed family membership on HIV risk behaviors among gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men in New Orleans. J Urban Health. 2018;95:179–87.

Grover E, Grosso A, Ketende S, Kennedy C, Fonner V, Adams D, et al. Social cohesion, social participation and HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Swaziland. AIDS Care. 2016;28(6):795–804.

Agampodi TC, Agampodi SB, Glozier N, Siribaddana S. Measurement of social capital in relation to health in low and middle income countries (LMIC): a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:95–104.

Khan MR, Miller WC, Schoenbach VJ, Weir SS, Kaufman JS, Wohl DA, et al. Timing and duration of incarceration and high-risk sexual partnerships among African Americans in North Carolina. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18(5):403–10.

Funding

This publication was made possible with support from the National Institute of Mental Health K01MH111374 (Yusuf Ransome), R01MH114657 (Philip Chan), R25MH083620 (Karlene Cunningham, Cassandra Sutten-Coates, Philip Chan, Dantrell Simmons, Tiara Willie, Amy Nunn), and National Institute on Drug Abuse T32DA13911 (Dantrell Simmons), National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism K01AA020228 (Amy Nunn).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Ethnical considerations reviewed and approved by institutional review boards at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, the Mississippi State Department of Health, and The Miriam Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Research Involving Human and Animal Rights

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.”

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ransome, Y., Cunningham, K., Paredes, M. et al. Social Capital and Risk of Concurrent Sexual Partners Among African Americans in Jackson, Mississippi. AIDS Behav 24, 2062–2072 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02770-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02770-8