Abstract

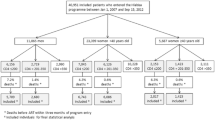

Despite a decade of advancing HIV/AIDS treatment policy in South Africa, 20% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) eligible for antiretroviral treatment (ART) remain untreated. To inform universal test and treat (UTT) implementation in South Africa, this analysis describes the rate, timeliness and determinants of ART initiation among newly diagnosed PLHIV. This analysis used routine data from 35 purposively selected primary clinics in three high HIV-burden districts of South Africa from June 1, 2014 to March 31, 2015. Kaplan–Meier survival curves estimated the rate of ART initiation. We identified predictors of ART initiation rate and timely initiation (within 14 days of eligibility determination) using Cox proportional hazards and multivariable logistic regression models in Stata 14.1. Based on national guidelines, 6826 patients were eligible for ART initiation. Under half of men and non-pregnant women were initiated on ART within 14 days (men: 39.7.0%, 95% CI 37.7–41.9; women: 39.9%, 95% CI 38.1–41.7). Pregnant women initiated at a faster rate (within 14 days: 87.6%, 86.1–89.0). ART initiation and timeliness varied significantly by district, facility location, and age, with little to no variation by World Health Organization stage, or CD4 count. Men and non-pregnant women newly diagnosed with HIV who are eligible for ART in South Africa show suboptimal timeliness of ART initiation. If treatment initiation performance is not improved, UTT implementation will be challenging among men and non-pregnant women. UTT programming should be tailored to district and location categories to address contextual differences influencing treatment initiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Johnson LF. Access to antiretroviral treatment in South Africa, 2004–2011. S Afr J HIV Med. pp. 22–7. http://www.sajhivmed.org.za/index.php/hivmed/article/view/156/261. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

SANAC. South African Global AIDS Response Progress Report. Pretoria, South Africa; 2015.

World Health Organization. WHO | Antiretroviral therapy and early mortality in South Africa. World Health Organization. http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/9/07-045294/en/. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

Shisana O, Rehle T, Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Jooste S, Zungu N, Labadarios D, Onoya DEA. South African National HIV prevalence, incidence and behaviour survey, 2012. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2014. p. 194.

UNAIDS. The gap report [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland; 2014. http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_Gap_report_en.pdf.

UNAIDS. 90-90-90 An ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. 2014;40. http://www.Unaids.Org/Sites/Default/Files/Media_Asset/90-90-90_En_0.Pdf.

World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. 2016. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/.

The National Department of Health. National Consolidated Guidelines for the prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the management of HIV in children, adolescents and adults. 2015.

World Health Organization. Use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/programmatic_update2012/en/.

UNICEF. Option B + countries and PMTCT regimen [Internet]. IATT website. 2015. http://emtct-iatt.org/b-countries-and-pmtct-regimen/.

Child K. Government updates HIV policy to allow ARV treatment for all South Africans. Times Live [Internet]. South Africa; 2016 May 10. http://www.timeslive.co.za/local/2016/05/10/Government-updates-HIV-policy-to-allow-ARV-treatment-for-all-South-Africans. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

van der Hoeven M, Kruger A, Greeff M. Differences in health care seeking behaviour between rural and urban communities in South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2012;11:31.

Ndawinz JDA, Chaix B, Koulla-Shiro S, Delaporte E, Okouda B, Abanda A, et al. Factors associated with late antiretroviral therapy initiation in Cameroon: a representative multilevel analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68:1388–99. https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkt011.

Musoke D, Boynton P, Butler C, Musoke MB. Health seeking behaviour and challenges in utilising health facilities in Wakiso district, Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2014;14:1046–55.

Aliyu MH, Blevins M, Parrish DD, Megazzini KM, Gebi UI, Muhammad MY, et al. Risk factors for delayed initiation of combination antiretroviral therapy in rural north central Nigeria. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65:e41–9.

Lahuerta M, Ue F, Hoffman S, Elul B, Kulkarni SG, Wu Y, et al. The problem of late ART initiation in Sub-Saharan Africa: a transient aspect of scale-up or a long-term phenomenon? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:359–83.

Fatukasi TV, Cole SR, Moore RD, Mathews WC, Edwards JK, Eron JJ, et al. Risk factors for delayed antiretroviral therapy initiation among HIV-seropositive patients. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0180843.

Mujugira A, Celum C, Thomas KK, Farquhar C, Mugo N, Katabira E, et al. Delay of antiretroviral therapy initiation is common in East African HIV-infected individuals in serodiscordant partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:436–42.

Ogoina D, Finomo F, Harry T, Inatimi O, Ebuenyi I, Tariladei W, et al. Factors associated with timing of initiation of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-1 infected adults in the Niger Delta Region of Nigeria. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0125665.

Abera Abaerei A, Ncayiyana J, Levin J. Health-care utilization and associated factors in Gauteng province, South Africa. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1305765.

Teasdale CA, Wang C, Francois U, Ndahimana JDA, Vincent M, Sahabo R, et al. Time to initiation of antiretroviral therapy among patients who Are ART eligible in Rwanda: improvement over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;68:314–21.

Odeny TA, DeCenso B, Dansereau E, Gasasira A, Kisia C, Njuguna P, et al. The clock is ticking: the rate and timeliness of antiretroviral therapy initiation from the time of treatment eligibility in Kenya. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:20019.

Kayigamba FR, Bakker MI, Fikse H, Mugisha V, Asiimwe A, Schim van der Loeff MF. Patient enrolment into HIV care and treatment within 90 days of HIV diagnosis in eight Rwandan health facilities: a review of facility-based registers. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e36792.

Murphy RA, Sunpath H, Taha B, Kappagoda S, Maphasa KTM, Kuritzkes DR, et al. Low uptake of antiretroviral therapy after admission with human immunodeficiency virus and tuberculosis in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:903–8.

MacLeod W, Fraser N, Shubber Z, Carmona S, Pillay Y, Gorgens M. Analysis of age-and sex-specific HIV care cascades in South Africa suggests unequal progress towards UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets. In: 21st International AIDS Conference Durban. 2016.

Grobler A, Kharsany A, Cawood C, Khanyile D, Puren A, Madurai L. Achieving UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets in a high HIV burden district in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. Durban: Int AIDS Conf; 2016.

Kranzer K, Govindasamy D, Ford N, Johnston V, Lawn SD. Quantifying and addressing losses along the continuum of care for people living with HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2012;15:17383.

Nair PS. Age structural transition in South Africa. Afr Popul Stud 2011. http://aps.journals.ac.za/pub/article/view/227. Accessed 9 Aug 2016.

McLaren Z, Brouwer E, Ederer D, Fischer K, Branson N. Gender patterns of tuberculosis testing and disease in South Africa. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:104–10.

Takarinda KC, Harries AD, Mutasa-Apollo T. Critical considerations for adopting the HIV “treat all” approach in Zimbabwe: is the nation poised? Public Heal Action. 2016;6:3–7.

Nakanyala T, Patel S, Sawadogo S, Maher A, Banda K, Wolkon A, et al. How close to 90-90-90? Measuring undiagnosed HIV infection, ART use and viral suppression in a community-based sample from Namibia’s highest prevalence region. In: 21st International AIDS Conference Durban. 2016;.

Kranzer K, Zeinecker J, Ginsberg P, Orrell C, Kalawe NN, Lawn SD, et al. Linkage to HIV care and antiretroviral therapy in Cape Town, South Africa. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e13801.

De Schacht C, Lucas C, Mboa C, Gill M, Macasse E, Dimande SA, et al. Access to HIV prevention and care for HIV-exposed and HIV-infected children: a qualitative study in rural and urban Mozambique. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:1240.

Mrisho M, Schellenberg JA, Mushi AK, Obrist B, Mshinda H, Tanner M, et al. Factors affecting home delivery in rural Tanzania. Trop Med Int Heal. 2007;12:862–72.

Auld AF, Shiraishi RW, Mbofana F, Couto A, Fetogang EB, El-Halabi S, et al. Lower levels of antiretroviral therapy enrollment among men with HIV compared with women—12 countries, 2002–2013. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:1281–6.

Tippet Barr B, Jahn A, Gupta S, Maida A, Chimbwandri F. Option B + in Malawi: have 4 years of “Treat All” shown that 90-90-90 is achievable? | In: CROI Conference. CROI Conference Boston. 2016. http://www.croiconference.org/sessions/option-b-malawi-have-4-years-treat-all-shown-90-90-90-achievable. Accessed 10 Aug 2016.

Remien RH, Chowdhury J, Mokhbat JE, Soliman C, El Adawy M, El-Sadr W. Gender and care: access to HIV testing, care, and treatment. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009. https://doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181aafd66.

Mugglin C, Estill J, Wandeler G, Bender N, Egger M, Gsponer T, et al. Loss to programme between HIV diagnosis and initiation of antiretroviral therapy in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health. 2012;17:1509–20.

Chimbwandira F, Mhango E, Makombe S, Midiani D, Houston J. Impact of an innovative approach to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV-Malawi. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2013;62:148–51.

Dellar RC, Dlamini S, Karim QA. Adolescent girls and young women: key populations for HIV epidemic control. J Int AIDS Soc. 2015;18:64–70.

Massyn N, Peer N, Padarath A, Barron P, Day C. District health barometer. Pretoria: Health Systems Trust; 2015.

Abay SM, Deribe K, Reda AA, Biadgilign S, Datiko D, Assefa T, et al. The effect of early initiation of antiretroviral therapy in TB/HIV-coinfected patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2015;14:560–70.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all those who participated in this study, all data collectors and supervisors, and members of the South Africa Howard University team. The research was performed by Howard University through a grant from the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number 1U2GGH000391.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

Funding

This study was funded by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief 1U2GGH000391.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Larsen, A., Cheyip, M., Tesfay, A. et al. Timing and Predictors of Initiation on Antiretroviral Therapy Among Newly-Diagnosed HIV-Infected Persons in South Africa. AIDS Behav 23, 375–385 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2222-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-018-2222-2