Abstract

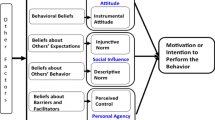

Slow adult male circumcision uptake is one factor leading some to recommend increased priority for infant male circumcision (IMC) in sub-Saharan African countries. This research, guided by the integrated behavioral model (IBM), was carried out to identify key beliefs that best explain Zimbabwean parents’ motivation to have their infant sons circumcised. A quantitative survey, designed from qualitative elicitation study results, was administered to independent representative samples of 800 expectant mothers and 795 expectant fathers in two urban and two rural areas in Zimbabwe. Multiple regression analyses found IMC motivation among fathers was explained by instrumental attitude, descriptive norm and self-efficacy; while motivation among mothers was explained by instrumental attitude, injunctive norm, descriptive norm, self-efficacy, and perceived control. Regression analyses of beliefs underlying IBM constructs found some overlap but many differences in key beliefs explaining IMC motivation among mothers and fathers. We found differences in key beliefs among urban and rural parents. Urban fathers’ IMC motivation was explained best by behavioral beliefs, while rural fathers’ motivation was explained by both behavioral and efficacy beliefs. Urban mothers’ IMC motivation was explained primarily by behavioral and normative beliefs, while rural mothers’ motivation was explained mostly by behavioral beliefs. The key beliefs we identified should serve as targets for developing messages to improve demand and maximize parent uptake as IMC programs are rolled out. These targets need to be different among urban and rural expectant mothers and fathers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Auvert B, Taljaard D, Lagarde E, Sobngwi-Tambekou J, Sitta R, Puren A. Randomized, controlled intervention trial of male circumcision for reduction of HIV infection risk: the ANRS 1265 Trial. PLoS Med. 2005;2(11):e298.

Bailey RC, Moses S, Parker CB, Agot K, Maclean I, Krieger JN, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in young men in Kisumu, Kenya: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):643–56.

Byakika-Tusiime J. Circumcision and HIV infection: assessment of causality. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):835–41.

Gray RH, Kigozi G, Serwadda D, Makumbi F, Watya S, Nalugoda F, et al. Male circumcision for HIV prevention in men in Rakai, Uganda: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9562):657–66.

WHO, UNAIDS. New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2007.

Awad SF, Sgaier SK, Ncube G, Xaba S, Mugurungi OM, Mhangara MM, et al. A reevaluation of the voluntary medical male circumcision scale-up plan in Zimbabwe. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(11):e0140818.

MOHCC. Global AIDS Response Report. Geneva, Switzerland: Ministry of Health and Child Care; 2016.

UNAIDS. Prevention Gap Report. 20 Avenue Appia CH-1211 Geneva 27 Switzerland: United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2016.

ZDHS. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2010-11. Calverton, Maryland; 2012.

ZDHS. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey: Key Indicators. Rockville, Maryland; Harare, Zimabwe: The DHS Program, ICF International; Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT). 2016.

Kalichman SC. Neonatal circumcision for HIV prevention: cost, culture, and behavioral considerations. PLoS Med. 2010;7(1):e1000219.

Montano DE, Kasprzyk D, Hamilton DT, Tshimanga M, Gorn G. Evidence-based identification of key beliefs explaining adult male circumcision motivation in Zimbabwe: targets for behavior change messaging. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):885–904.

Binagwaho A, Pegurri E, Muita J, Bertozzi S. Male circumcision at different ages in Rwanda: a cost-effectiveness study. PLoS Med. 2010;7(1):e1000211.

Morris BJ, Waskett JH, Banerjee J, Wamai RG, Tobian AA, Gray RH, et al. A ‘snip’ in time: what is the best age to circumcise? BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:20.

Mavhu W, Hatzold K, Laver SM, Sherman J, Tengende BR, Mangenah C, et al. Acceptability of early infant male circumcision as an HIV prevention intervention in Zimbabwe: a qualitative perspective. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(2):e32475.

Mavhu W, Larke N, Hatzold K, Ncube G, Weiss HA, Mangenah C, et al. Implementation and operational research: a randomized noninferiority trial of accucirc device versus mogen clamp for early infant male circumcision in Zimbabwe. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2015;69(5):e156–63.

Sinkey RG, Eschenbacher MA, Walsh PM, Doerger RG, Lambers DS, Sibai BM, et al. The GoMo study: a randomized clinical trial assessing neonatal pain with Gomco vs Mogen clamp circumcision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212(5):664.

Morris BJ, Wiswell TE. Circumcision and lifetime risk of urinary tract infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Urol. 2013;189(6):2118–24.

Albert LM, Akol A, L’Engle K, Tolley EE, Ramirez CB, Opio A, et al. Acceptability of male circumcision for prevention of HIV infection among men and women in Uganda. AIDS Care. 2011;23(12):1578–85.

Mavhu W, Buzdugan R, Langhaug LF, Hatzold K, Benedikt C, Sherman J, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with knowledge of and willingness for male circumcision in rural Zimbabwe. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16(5):589–97.

Mugwanya KK, Whalen C, Celum C, Nakku-Joloba E, Katabira E, Baeten JM. Circumcision of male children for reduction of future risk for HIV: acceptability among HIV serodiscordant couples in Kampala, Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22254.

Plank RM, Makhema J, Kebaabetswe P, Hussein F, Lesetedi C, Halperin D, et al. Acceptability of infant male circumcision as part of HIV prevention and male reproductive health efforts in Gaborone, Botswana, and surrounding areas. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(5):1198–202.

Rediger C, Muller AJ. Parents’ rationale for male circumcision. Can Fam Phys. 2013;59(2):e110–5.

Jarrett P, Kliner M, Walley J. Early infant male circumcision for human immunodeficiency virus prevention: knowledge and attitudes of women attending a rural hospital in Swaziland, Southern Africa. SAHARA J. 2014;11:61–6.

Mavhu W, Mupambireyi Z, Hart G, Cowan FM. Factors associated with parental non-adoption of infant male circumcision for HIV prevention in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and thematic synthesis. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1776–84.

Waters E, Stringer E, Mugisa B, Temba S, Bowa K, Linyama D. Acceptability of neonatal male circumcision in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Care. 2012;24(1):12–9.

Young MR, Odoyo-June E, Nordstrom SK, Irwin TE, Ongong’a DO, Ochomo B, et al. Factors associated with uptake of infant male circumcision for HIV prevention in western Kenya. Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):e175–82.

Waters E, Li M, Mugisa B, Bowa K, Linyama D, Stringer E, et al. Acceptability and uptake of neonatal male circumcision in Lusaka, Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2114–22.

Montano DE, Kasprzyk D. Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. In: Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K, editors. Health behavior: theory, research, and practice. 5th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2015. p. 95–124.

Kasprzyk D, Tshimanga M, Hamilton DT, Gorn GJ, Montano DE. Identification of key beliefs explaining male circumcision motivation among adolescent boys in Zimbabwe: targets for behavior change communication. AIDS Behav. 2017. doi:10.1007/s10461-016-1664-7.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Predicting and changing behavior: the reasoned action approach. New York: Psychology Press, Taylor & Francis Group; 2010.

Bandura A. Social cognitive theory and control over HIV infection. In: DiClemente RJ, Peterson JL, editors. Preventing AIDS: theories and methods of behavioral interventions. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. p. 25–59.

Ajzen I. Martin Fishbein’s legacy: the reasoned action approach. In: Hennessy M, editor. The Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 640. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012. pp. 11–27.

Bleakley A, Hennessy M. The quantitative analysis of reasoned action theory. In: Hennessy M, editor. The Annals of The American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 640. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2012. pp. 28–41.

Fishbein M, Cappella JN. The role of theory in developing effective health communications. J. Commun. 2006;56:S1–17.

Kasprzyk D, Montano DE. Application of an integrated behavioral model to understand HIV prevention behavior of high-risk men in rural Zimbabwe. In: Ajzen I, Albarracin D, Hornik R, editors. Prediction and change of health behavior: applying the reasoned action approach. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; 2007.

von Haeften I, Fishbein M, Kasprzyk D, Montano D. Analyzing data to obtain information to design targeted interventions. Psychol Health Med. 2001;6(2):151–64.

Sheeran P. Intention-behavior relations: A conceptual and empirical review. In: Stroebe W, Hewstone M, editors. European review of social psychology. Chichester: Wiley; 2002.

Webb TL, Sheeran P. Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychol Bull. 2006;132(2):249–68.

Acknowledgements

The research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01MH083594. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We would like to acknowledge the study participants and the University of Zimbabwe, Department of Community Medicine ZiCHIRe Program study team for their enthusiastic participation in all phases of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Daniel Montaño, Mufuta Tshimanga, Deven Hamilton, Gerald Gorn, and Danuta Kasprzyk each declares that he/she has no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human subjects were in accordance with the ethical standards of the US institutional IRB and the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montaño, D.E., Tshimanga, M., Hamilton, D.T. et al. Evidence-Based Identification of Key Beliefs Explaining Infant Male Circumcision Motivation Among Expectant Parents in Zimbabwe: Targets for Behavior Change Messaging. AIDS Behav 22, 479–496 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1796-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1796-4