Abstract

This paper identifies the empirical stylized features of consumer price setting behavior in Portugal using two micro-datasets underlying the consumer price index. The main conclusions are: one in every four prices change each month; there is a considerable degree of heterogeneity in price setting practices; prices of goods change more often than prices of services; price reductions are common, as they account to around 40% of total price changes; price changes are, in general, sizeable; finally, the price setting patterns seem to depend on the level of inflation as well as on the type of outlet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Some examples are Caucutt et al. (1999) on the rigidity of prices over the business cycle and the importance of durability and seller concentration, Lach (2002) on the dispersion of prices across store and their persistence over time, or Hall et al. (1997) on the extent of price rigidities and the importance of firms and market factors.

See MacDonald and Aaronson (2000), Lach and Tsiddon (1992, 1996), Kashyap (1995), Eichenbaum and Fisher (2003) or Konieczny and Skrzypacz (2003). As they stand, many of the theories make few predictions apart from price rigidity, and the few predictions they make are often on immeasurable or unmeasured variables. This strongly compromises the chances of empirically confirming them (see the discussion in Blinder 1994).

The most detailed product code is composed of eight digits. The first five digits identify the class, group, subgroup and sub-subgroup; the last three digits identify the specific good or service chosen for the sample. To guarantee statistical secrecy, the key provided by INE only identifies the first five digits.

The goal of this paper is to characterize the price setting behaviour in Portugal during “normal” periods. For that reason we opted to exclude the euro cash changeover from the analysis.

INE (1992) describes the main features concerning sample definition, selection and size.

The rotating data collection scheme means that prices are reported every month for all products.

About 2.2% of the observed prices are flagged as sales or promotions in CPI2.

The data being used here is not afflicted by the non-randomness characteristic of stock samples since what is sampled is items in stores, not price spells. For the items in stores, we observe their prices for a certain period of time, in a succession of contiguous spells.

See, for instance, Lancaster (1990) for a discussion on renewal process theory.

Alternative parametric assumptions, allowing or not for duration dependency, could be considered. An extreme alternative is, for example, that any given item in an outlet experiences, at the most, one price change within a quarter, meaning that \(f_1 = {{f_3 } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{f_3 } 3}} \right. \kern-\nulldelimiterspace} 3}\). At the other extreme is the assumption that an outlet changing the price of an item decides to do it repeatedly in every month within the quarter, meaning that f 1 = f 3.

Baharad and Eden (2004), in their study for Israel, obtain a median average duration of 8 and 4 months using the frequency of price changes estimated at the product*outlet and product level, respectively. We have obtained similar results for Portugal (presented below).

These values are the inverse of the median average frequency of price changes (second column of Table 1).

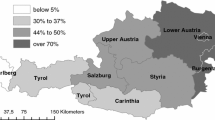

Large, medium and small outlets were considered separately, corresponding to hypermarkets, supermarkets and classical stores, respectively.

Results available under request from the authors.

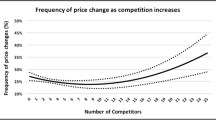

Moreover, economies of scale in the price setting activity are also expected.

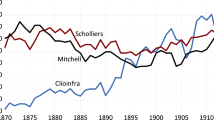

Over 1997–2002, the period covered by CPI2, the rate of inflation fluctuated in a much more narrow band. This justifies the focus on the sample CPI1 to highlight this point.

The two datasets are expected to exhibit different patterns as they are based in different methodologies, cover a different bundle of goods and use different weights. In particular, higher frequencies and more variability over time are expected under CPI2 given that promotions are included in the price.

The analysis of each quarter in each year separately was also performed. However, homologous quarters in different years exhibit undistinguishable distributions for the rate of price changes. Therefore, we opted for considering them together.

Tukey’s definition of outliers was applied to the distribution of price changes (conditional on the occurrence of a price change): outliers are defined as observations that lie above (below) 1.5 times the inter-quartile range of the price changes distribution (this covers both suspected outliers and outliers).

Klenow and Kryvtsov (2005) report a frequency of around 1.5 per cent for non-comparable replacements in the micro data collected by the US Bureau of Labour Statistics and Hoffmann and Kurz-Kim (2006) estimated a maximum impact of 1.4% on the overall frequency of price changes due to the existence of non-observed replacements.

Results available from the authors upon request.

References

Baharad E, Eden B (2004) Price rigidity and price dispersion: evidence from micro-data. Rev Econ Dyn 7(2004):613–641

Baudry L, Bihan H, Sevestre P, Tarrieu S (2004) Price rigidity in France: some evidence from consumer price micro-data. European Central Bank working paper n. 384

Bils M, Klenow P (2004) Some evidence on the importance of sticky prices. J Polit Econ 112:947–985

Blinder A (1994) On sticky prices: academic theories meet the real world. In: Mankiw NG (ed) Monetary policy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 117–150

Caplin A, Spulber D (1987) Menu costs and the neutrality of money. Q J Econ 102(4):703–726

Caucutt E, Ghosh M, Kelton C (1999) Durability versus concentration as an explanation for price inflexibility. Rev Ind Organ 14(1):27–50

Dhyne E, Alvarez L, Le Bihan H, Veronese G, Dias D, Hoffmann J, Jonker N, Lunnemann P, Rumler F, Vilmunen J (2006) Price changes in the Euro Area and the United States: some facts from individual consumer price data. J Econ Perspect 20(2):171–192 (Spring)

Eichenbaum M, Fisher J (2003) Testing the Calvo model of sticky prices. Econ Perspect 2Q:40–53 (Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago)

Hall S, Walsh M, Yates A (1997) How do UK companies set prices? Bank of England

Hoffmann J, Kurz-Kim J (2006) Consumer price adjustment under the microscope: Germany in a period of low inflation. European Central Bank, W.P. No. 652

INE (1992) Índice de preços no consumidor. Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Série estudos no. 58

Kashyap A (1995) Sticky prices: new evidence from retail catalogs. Q J Econ 110(1):245–274

Klenow P, Kryvtsov O (2005) State-dependent or time-dependent pricing: does it matter for recent U.S. inflation? Bank of Canada, Working Paper 2005-4

Konieczny J, Skrzypacz A (2003) A new test of the menu cost model. mimeo

Lach S (2002) Existence and persistence of price dispersion: an empirical analysis. Rev Econ Stat 84(3):433–444

Lach S, Tsiddon D (1992) The behaviour of prices and inflation: an empirical analysis of disaggregate price data. J Polit Econ 100(2):349–389

Lach S, Tsiddon D (1996) Staggering and synchronization in price setting: evidence from multiproduct firms. Am Econ Rev 86(5):1175–1196

Lancaster T (1990) The econometric analysis of transition data. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

MacDonald J, Aaronson D (2000) How do retail prices react to minimum wage increases? Federal Reserve bank of Chicago WP 2000–20

Taylor J (1999) Staggered price and wage setting in macroeconomics. In: Taylor JB, Woodford M (eds) Handbook of macroeconomics, vol. 1b. North-Holland, Amsterdam

Tsiddon D (1991) On the stubbornness of sticky prices. Int Econ Rev 32(1):69–75

Wolman A (2001) A primer on optimal monetary policy with staggered price-setting. Econ Q 87(4):27–52 (Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond)

Acknowledgments

We thank Nuno Alves, Carlos Robalo Marques, João Santos Silva, Maximiano Pinheiro, Pedro Pita Barros, participants at various meetings of the Inflation Persistence Network of the Eurosystem, two anonymous referees and especially Hervé Le Bihan for many useful comments at different stages of this project. We are also grateful to Daniel Santos, Cristina Cabral, Cristina Fernandes and Humberto Pereira, from the Instituto Nacional de Estatística, for many helpful discussions concerning the methodological aspects of the datasets. The usual disclaimer applies

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This paper is based on the working paper of Costa Dias M, Dias D, Neves PD (2004) Stylised features of price setting behavior in Portugal: 1992–2001. Banco de Portugal, W. P. No. 2004–5 and European Central Bank, W. P. No. 332.

Appendices

Appendix A: data

This appendix describes the key aspects concerning data collection in CPI2.

1.1 A.1. Data issues

The following table summarizes the main features of the CPI2 that may affect the values and interpretation of the statistics reported in the text on frequency and magnitude of price changes.

1.2 A.2. Forced item substitutions in the CPI2

Forced item substitutions may occur in the CPI2. In these cases, a comparable or non-comparable substitute is selected depending on whether or not a comparable substitute exists in the store. When a non-comparable substitute must be selected, an adjustment reflecting the quality change, products upgrade or model changeover needs to be considered for the purpose of computing the price index.

Unfortunately, there is no code in the CPI2 dataset to signal non-comparable items’ substitution. However, there is information at the regional level about whether at least one non-comparable replacement occurred in a store within the respective region. We use this information to assess the importance of this type of replacements in our results. When non-comparable replacements occurred in a region at a period in time, we assumed any outliers in the magnitude of price change identified such replacements.Footnote 20 When no outliers occurred, the highest (absolute) price change was selected instead. This procedure suggests that 1% of the overall month-to-month transitions are affected by non-comparable replacements.Footnote 21 A new spell starts each and every time such an occurrence of a non-comparable replacement is estimated.

In order to assess the robustness of the results reported in the paper, four alternative cases were considered:

-

(a)

No treatment of non-comparable substitutions: this corresponds to an upper bound to both the frequency and the magnitude of price changes;

-

(b)

Estimation of non-comparable substitutions: this procedure (described above) was used to compute the estimates discussed in the main text;

-

(c)

Elimination of all the observations concerning price changes at the item/region level for which we know that at least one non-comparable replacement took place: this corresponds to a lower bound for the frequency of price changes;

-

(d)

As an additional sensitivity exercise, we also considered a situation in which all the price sequences (i.e. price changes and no price changes) at the item/region level for which we know that (at least) one non-comparable replacement took place were eliminated.

The empirical results reported are robust to the alternative assumptions considered.Footnote 22

Appendix B: Estimation of monthly figures from quarterly data—adequacy of adopted methodology

As described in Section 2, both CPI datasets have monthly, quarterly and annual data, raising some comparability problems. To overcome this, we have discarded items with annual observations only and have estimated the monthly figures from quarterly data. The later procedure is expected to produce biased estimates. We evaluate how serious this bias can be in this appendix. To do this, we restrict the analysis to items observed monthly and estimate the true and estimated monthly frequencies of price change for these items only. Estimated monthly frequencies of price change are obtained for quarterly data constructed from monthly data by discarding information on 2 months out of every quarter. The same procedure was applied to the magnitude of price changes. The obtained bias, the difference between the true and the estimated monthly figures, is described in Tables 5 and 6 in Appendix A. The results show that the estimation of monthly figures from quarterly data does not seem to create significant bias.

About this article

Cite this article

Costa Dias, M., Dias, D.A. & Duarte Neves, P. Stylised features of consumer price setting behaviour in Portugal: 1992–2001. Port Econ J 7, 75–99 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-008-0028-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10258-008-0028-2