Abstract

This study evaluated the role of temporal fine structure in the lateralization and understanding of speech in six normal-hearing listeners. Interaural time differences (ITDs) were introduced to invoke lateralization. Speech reception thresholds (SRTs) were evaluated in backgrounds of two-talker babble and speech-shaped noise. Two-syllable words with ITDs of 0 and 700 μs were used as targets. A vocoder technique, which systematically randomized fine structure, was used to evaluate the effects of fine structure on these tasks. Randomization of temporal fine structure was found to significantly reduce the ability of normal-hearing listeners to lateralize words, although for many listeners, good lateralization performance was achieved with as much as 80% fine-structure randomization. Most listeners demonstrated some rudimentary ability to lateralize with 100% fine-structure randomization. When ITDs were 0 μs, randomization of fine structure had a much greater effect on SRT in two-talker babble than in speech-shaped noise. Binaural advantages were also observed. In steady noise, the difference in SRT between words with 0- vs 700-μs ITDs was, on average, 6 dB with no fine-structure randomization and 2 dB with 100% fine-structure randomization. In two-talker babble this difference was 1.9 dB and, for most listeners, showed little effect of the degree of fine-structure randomization. These results suggest that (1) improved delivery of temporal fine structure would improve speech understanding in noise for implant recipients, (2) bilateral implant recipients might benefit from temporal envelope ITDs, and (3) improved delivery of temporal information could improve binaural benefits.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Interaural time differences (ITDs) contribute to important real-world tasks such as localization ability (Rayleigh 1907; Wightman and Kistler 1992) and binaural unmasking (Carhart et al. 1967; Bronkhorst and Plomp 1988; Culling et al. 2004). Real environmental sounds provide ITDs with both envelope and fine structure. At low frequencies (<1.5 kHz) for stimuli longer than 100 ms, fine-structure ITDs dominate perception (Tobias and Schubert 1959); however, both envelope and fine-structure ITDs contribute to lateralization ability (Klumpp and Eady 1956; Yost et al. 1971; Henning 1974; McFadden and Pasanen 1976; Van de Par and Kohlrausch 1997), binaural unmasking (Van de Par and Kohlrausch 1997; Long et al. 2006), and segregation ability (Drennan et al. 2003; Best et al. 2004).

Common cochlear implant sound processing strategies do not explicitly encode temporal fine-structure information, but only the envelope information. While some fine-structure information for low frequencies is passed through the temporal envelope, most temporal fine-structure information is lost in processing. Previous observations that envelope ITDs contribute to lateralization and segregation in normal-hearing listeners is beneficial for bilateral implantees because this means it would be theoretically possible for implantees to glean some benefit from interaural timing differences. Temporal fine structure is also known to provide information, which help normal-hearing humans perceive music (Smith et al. 2002), speech in noise (Kong et al. 2005), and tonal languages (Xu and Pfingst 2003). Hence, improved delivery of temporal fine structure should help monaural and binaural implantees. This study evaluates the role of fine structure in practical tasks such as the lateralization of speech and speech understanding in noise. A key motivation is to better understand how improved delivery of fine structure could improve hearing in implantees. Insights into the role of fine structure in practical hearing tasks could lead to improvements in cochlear implant sound processing.

In this study, we presented vocoder-processed sounds to normal-hearing listeners. The vocoder divided the signal into six band-pass channels. A signal processing technique enabled graded randomization of the fine structure, but preserved the temporal envelope of the waveforms. The procedure offers the unique capability to systematically vary the extent of the randomization of the fine structure to quantify the effect of temporal fine structure on human auditory processing capabilities. This study served two purposes, one scientific and one clinical: (1) to determine the extent to which temporal fine structure contributes to lateralization and speech understanding in noise, and (2) to evaluate how improved fine-structure delivery might improve these capabilities.

METHODS

Bilateral cochlear implant simulations were presented to normal-hearing listeners who had thresholds of less than 25 dB HL at all audiometric frequencies. Six listeners participated in the study. The stimuli were presented over TDH-50P headphones via a Macintosh G4 laptop in a quiet room. Speech levels were calibrated at 65 dBA. Listeners’ ages ranged from 26–38 with a mean of 32.3 years. They included two women and four men who volunteered their time for the study. The study was approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

A diagram of the fine-structure randomization procedure is shown in Figure 1. The stimulus, X(t), was passed through a bank of 6 band-pass FIR filters. The filters covered the logarithmically spaced frequency ranges of 80–308, 308–788, 788–1794, 1794–3906, 3906–8338, and 8,338–17,640 Hz. A Hilbert transform was used to extract the envelope and fine structure of each filter. A random component was added to the Hilbert phase and then was weighted by a noise factor, NF, which varied from 0 to 1. The NF represents the extent of randomization of the fine structure such that NF = 1 was 100% fine-structure randomization and NF = 0 was only filtered, keeping the fine structure identical to the original signal. This NF concept was first introduced by Rubinstein and Turner (2003). In signal processing terms, the NF determined the extent of randomization of the Hilbert phase from 0 to 100%. A sequence of identically distributed uniform random variables from 0 to 1, r i (t), was multiplied by 2π times the NF and added to the Hilbert phase of the original stimulus (see Eq. 1). The randomized fine structure was filtered by B i (t), and the output was multiplied by the Hilbert envelope of the original stimulus. This procedure is represented analytically by the following equation operating on the output of a single channel:

in which y i (t) is the output stimulus, x i (t) is the filtered stimulus, H(x i (t)) is the Hilbert transform, B i (t) is the impulse response of the ith band pass filter, “*” indicates convolution, r i (t) is a sequence of uniformly distributed random variables from 0 to 1, and n is the NF. All six channels are summed to create the output signal Y(t). Randomization of phase was independent for the two ears and for each band. Using this approach, psychophysical abilities were evaluated as a function of the NFs ranging from 0 (no randomization, i.e., the original stimulus filtered) to 1 (complete randomization equivalent to a traditional 6-channel, vocoder-type, noise-band cochlear implant simulation, e.g., Shannon et al. 1995). In experiments with background noise, ITDs were introduced to the signal before NF processing. The sum of the signal and noise (X(t)) was then processed using Eq. 1.

Schematic of signal processing to randomize fine structure showing an acoustic signal X(t) that passed through 1 of 6 BPFs to create x i (t). A An example filtered wave. The band-passed waveform was then passed through a Hilbert transform. B The resultant example envelope and fine-structure waves are shown with the randomized fine structure. C, D The Hilbert phase was added to a sequence of uniform random variables r i (t), that were weighted by NF (C), and then filtered again with the same band pass filter (D). E The final wave was multiplied by the original Hilbert envelope to produce band-specific randomized fine structure bearing nearly the original envelope. The same processing was executed with all six bands, which were summed to create the signal with randomized fine structure.

The process of introducing fine-structure randomization and refiltering could alter the envelope. When comparing the “target” envelope before processing and the output envelope for single pass bands, the correlations were 0.98–0.99. Thus, the effect of fine-structure randomization on the envelope was slight.

Lateralization

Two spondees, “padlock” and “stairway,” were chosen, because they had robust low-frequency energy. A 6 × 4 repeated-measures design was used with 6 NFs and 4 repetitions. The spondees were presented to listeners using NFs of 0, 0.5, 0.7, 0.8, 0.9, and 1. The ITD conditions were −750, −500, −250, 0, 250, 500, and 750 μs. Listeners responded using a computer mouse, clicking on one of seven boxes on a monitor labeled L3, L2, L1, C, R1, R2, and R3 for each ITD. Each listener had a short training period in which they could listen to each spondee with any ITD by clicking on the response box. Listeners completed training runs with the higher NFs until they did not demonstrate improvement. After training, participants completed 42 lateralization judgments per run including 3 judgments for each word at each ITD. Four runs were completed for each listener with each NF. The order of presentation was randomized in the following manner: an NF was selected randomly from the set of six, 42 presentations including 6 at each ITD were presented in a random order using that NF, then a different NF was selected and the process repeated. Listeners thus heard 42 presentations with 1 NF before moving onto another NF. Performance was evaluated using r 2, based on the correlation of the actual ITD vs the response ITD (Good and Gilkey 1996). This metric was chosen to look specifically at lateralization ability because a variety of biases could be observed (left side, right side, and center), which would yield extremely poor accuracy even if the listener had reasonable sensitivity to ITDs. That is, biases using other measures, such as percent correct, could hide true lateralization ability.

Binaural intelligibility level difference

The binaural intelligibility level difference (BILD) refers to an intelligibility advantage a listener can obtain when listening to speech in noise if the binaural timing or phase of the speech differs from that of the noise (Bronkhorst and Plomp 1988). A speech reception threshold (SRT) is the signal to noise ratio (S/N) at which speech is intelligible. In this case, S/N for the 50% intelligibility level (the SRT) was determined for speech in two conditions in which the ITDs of the speech differed. Binaural intelligibility level differences were calculated by determining the difference between the SRT for spondees with 0 and 700-μs ITDs. This was done four times with two types of background noise, steady-state, speech-shaped noise, and two-talker babble with a variety of NFs. The final analysis was 4 × 2 × 5 using 4 repetitions, 2 types of noise background, and 5 NFs.

On each trial, normal-hearing listeners identified 1 of 12 equally difficult spondees (Harris 1991) presented in one of the two noise backgrounds. The babble consisted of one male and one female talker using a sentence from the SPIN test (Bilger et al. 1984). The target spondees were all spoken by a female talker, different from the female talker in the babble. To minimize variance that might result from variable difficulty by using different babble backgrounds on each trial, i.e., to get the least noisy measure of SRT in the babble, the same babble background was used on every trial. The male talker spoke the sentence “Name two uses for ice,” and the female talker spoke the sentence “Bill might discuss the foam.” The target speech (the spondee) was delayed from the onset of the babble by 500 ms. In the steady noise background, the same noise was used on every trial, and the spondees were delayed by 500 ms relative to the start of the noise. Both the target and noise were processed with fine-structure (Hilbert phase) randomization, independently processed for the two ears. The spondees were presented with ITDs of 0 or 700 μs. Noise factors were 0, 0.5, 0.75, 0.875, and 1. A one-down, one-up adaptive tracking procedure was used in which noise levels were tracked in 2-dB increments to determine an SRT representing 50% correct. In the NF = 0 condition using babble background, the S/N ratio dropped below −40 dB. In this case, the listeners were permitted to lower the overall level about 5 dB because background noise was quite loud. The 12-spondee closed set discrimination task and tracking procedure were the same as used by Turner et al. (2004). One run consisted of 14 reversals in which the threshold was the mean of the last 10 reversals. Four tracking histories were completed for each condition. The order of presentation was randomized in the following way: one of the NFs was selected randomly, then listeners completed all four runs (two in babble and two in steady noise, with ITDs = 0 and 700 μs) presented in a random order using that specific NF. Then, a different NF was selected randomly, and listeners completed the four conditions (two noise backgrounds and two ITDs) in a newly randomized order. This procedure continued until all conditions were finished. Each listener had a different randomized order of presentation for both the NFs and the four conditions run with each NF. Listeners completed all NF conditions for the first repetition before moving on to the second repetition.

RESULTS

Lateralization

Figure 2 shows the individual lateralization results as a function of the NF. Figure 3 shows the mean lateralization results. Error bars in all figures show the 95% confidence interval. A 6 × 4 repeated measures ANOVA (6 NFs and 4 repetition times) demonstrated that, as expected, there was a significant effect of NF (F 5,25 = 17.831, p < 0.0005). There was no effect of repetition time demonstrating there was no learning trend in this task. The mean r 2 for lateralization was above chance for NF = 1 (p = 0.0093), with 100% fine-structure randomization, suggesting that most listeners could lateralize without fine-structure ITD information. This is consistent with previous observations that normal-hearing listeners can detect the ITD of the envelope alone (McFadden and Pasanen 1976). There were also substantial variations among listeners when 50% or more of the fine structure was randomized. A few listeners (L1 and L4) were only slightly affected by 50% fine-structure randomization, whereas others (L3, L5, L6, and L7) were greatly affected by this randomization.

Speech understanding

Figure 4 shows individual data from the speech-in-noise experiments in which the ITD = 0 μs. Figure 5 shows mean data. A 2 × 5 × 4 repeated-measures ANOVA (2 noise backgrounds, 5 NFs, and 4 repetition times) demonstrated that there was a main effect of the NF (F 4,20 = 126.5, p < 0.0005), an interaction between NF and noise background (F 4,20 = 34.308), p < 0.0005), and a main effect of the noise background (F 1,4 = 96.306, p < 0.0005). The main effect of noise background demonstrated that speech understanding in babble was usually better than speech understanding in speech-shaped noise. The interaction demonstrated that fine-structure randomization improved SRTs much more in babble than in steady-state noise. As reflected in the interaction, the difference in SRT between the two background noises was not significant when the NF was 1 (100% fine-structure randomization). We note that in babble, the thresholds for NF = 0 were extremely low, in the range of −35 to −40 dB S/N. These results were slightly lower than those of Turner et al. (2004) who found −30 dB for a similar condition. The primary difference between studies was that the present study used more reversals and more repetitions to determine a threshold. Also, different groups of listeners could have different capabilities.

For ITD = 0 μs, there was a main effect of repetition number (F 3,15 = 7.951, p < 0.002); an interaction between repetition number and noise background (F 3,15 = 5.222, p < 0.011); a weak interaction between repetition and NF (F 12,60 = 1.914, p < 0.05); and a three-way interaction among repetition time, NF, and noise background (F 12,60 = 2.280, p < 0.018). The effects of repetition time indicated that there was some improvement over time in the SRT; however, the interactions suggest that this improvement over time was limited to higher NFs in the babble background. For NFs of 0.75, 0.875, and 1 in the babble background, SRTs improved by about 6 dB from the first to the fourth time of testing, suggesting that for the spondees presented in babble, the listeners learned to make use of envelope cues without fine structure or learned how to listen in the silent gaps. In all the other conditions, for speech-shaped noise with all NFs and for two-talker babble backgrounds with NF = 0 or 0.5, there was little effect of repetition time. We also found similar learning trends in real cochlear implantees using the same methods for evaluation of SRTs (Won et al. 2007, submitted).

Binaural intelligibility level difference

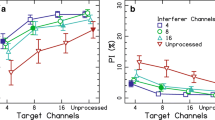

Figure 6 shows individual BILDs based on ITDs for spondees in babble and speech-shaped noise as a function of the NF. The BILD is calculated by subtracting the SRT for ITD = 700 μs from the SRT for ITD = 0 μs. Figure 7 shows mean BILD data. The result shows the extent to which fine structure contributes to ITD-only binaural advantages in normal-hearing listeners. A 2 × 5 × 4 repeated-measures ANOVA (2 noise backgrounds, 5 NFs, and 4 repetition times) was conducted. A main effect of noise background (F 1,5 = 13.799, p < 0.014) and a main effect of NF (F 4,20 = 5.441, p < 0.004) were observed. All other effects, including the effect of repetition time and associated interactions, were not significant. This lack of interaction of the BILD with the main factor of repetition time suggested that any learning that occurred was statistically equivalent for 0- and 700-μs ITDs. Binaural intelligibility level differences were generally larger in speech-shaped noise than in a babble background, which was shown by the main effect of noise background. Binaural intelligibility level differences decrease as the amount of fine structure decreases (i.e., as the NF increases), demonstrated by the main effect of NF. The BILD for NF = 0 in speech-shaped noise was about 6 dB on average, consistent with previous observations (e.g., Carhart et al. 1967; Bronkhorst and Plomp 1988). In two-talker babble, the effect of fine structure on the BILD was highly variable among listeners and did not appear to change much as fine-structure randomization increased, averaging about 1.9 dB across all NFs. Binaural intelligibility level differences for speech-shaped noise were more consistent among listeners and declined monotonically from about 6 dB for NF = 0 to 1.1 dB for NF = 1. Thus, the effect of fine structure for binaural cues appeared to be greater in speech-shaped noise than in two-talker babble.

Binaural intelligibility level difference as a function of noise factor (fine-structure randomization) for six individual listeners for spondees in two-talker babble and in steady-state, speech-shaped noise. Error bars show the 95% confidence interval based on four repeated measures for each listener.

DISCUSSION

In the first experiment, lateralization became more difficult with increased fine-structure randomization (Figs. 2 and 3). The results demonstrated the dominance of fine structure (relative to envelope) in lateralization based on ITDs. There was some lateralization ability even with 100% fine-structure randomization, but performance was greatly enhanced by fine structure. The result might also underestimate the effect of fine structure because the interaural level differences were 0, which could push the percept toward center, although center bias was only apparent in the high-NF conditions when r 2 values were low.

The results from the listeners least affected by fine-structure randomization paralleled results from Jeffress et al. (1962) in which listeners centered noises by adjusting the ITD of noises at the two ears. They found that listeners could center a noise image well when the interaural correlation was as low as 0.2. The fine structure of the noise bands in the present experiment were individually uncorrelated, making the experimental conditions similar to those of Jeffress et al., but the stimuli in the present experiment had some interaural correlation, even at NF = 1 because the temporal envelopes in each band matched.

The listeners showed some lateralization ability even when the NF was 1, suggesting sensitivity to envelope ITDs. With current processing schemes, using acoustic presentations and unsynchronized bilateral processors, implant users can detect envelope ITDs as demonstrated with click trains (Laback et al. 2004). This suggests that lateralization in implantees based on ITDs is possible and increased delivery of fine structure would enhance the utility of ITD cues.

For those implanted bilaterally, the place of current delivery for a specific frequency might be mismatched between the two ears, possibly resulting in decreased coincident detection in the medial superior olive (Jeffress 1948, 1958). To date, commercial cochlear implants are not synchronized bilaterally, so there is a potential for bilateral drift of ITDs based on the slight variations in the pulse rates between implants. However, the problem is alleviated with higher pulse rates, e.g., above about 2,000 pps because the ITDs of individual pulses are not discernable. Also, if an individual were deaf during a critical period in development, the binaural hearing system might not have developed normally. Nevertheless, sensitivity to ITDs was demonstrated in implantees (Long et al. 2003; Van Hoesel and Tyler 2003; Laback et al. 2004) and, given the dominance of fine structure for lateralization in normal-hearing listeners, improving the delivery of fine structure could greatly enhance the utility of ITD information in bilateral implantees.

For the case in which ITD = 0 μs, the effect of randomization of fine structure was much greater in babble than in speech-shaped noise (Figs. 4 and 5). In babble, improved spectral and temporal information would enhance the ability of listeners to segregate the male and female voices based on fundamental frequency (F0) (Brokx and Nooteboom 1982; Assmann and Summerfield 1990; Culling and Darwin 1993; Bird and Darwin 1998; Qin and Oxenham 2005). Hearing the individual F0s of each voice requires good spectral resolution and accurate perception of the temporal fine structure, which contributes to the perception of periodicity pitch for the low-frequency, resolved harmonics (Plomp 1967; Houtsma and Smurzynski 1990; Meddis and O’Mard 1997). Voices can be segregated based on the pitch manifested from the encoding of temporal fine structure (Qin and Oxenham 2003; Kong et al. 2005; Qin and Oxenham 2006). The effect of fine structure was less in speech-shaped noise because there was no pitch-basis to segregate the target speech from the background. Thus, fine-structure randomization appeared to significantly reduce the ability to segregate based on F0.

Normal-hearing listeners benefit both from increased spectral and temporal information with increased fine structure, but we would not expect the extent of spectral information to increase as dramatically in cochlear implant users because nerve survival and current spread are likely to limit the number of channels that can be resolved. Previous studies have demonstrated a limit in the spectral processing capability of cochlear implantees to about nine channels (e.g., Fishman et al. 1997; Dorman et al. 1998; Friesen et al. 2001). Whereas decreases in SRT with ITD = 0 could result from temporal and spectral degradation, decreases in binaural unmasking with increased fine-structure randomization must result from temporal factors because spectral factors do not play a role in ITD-only tasks. An attractive feature of tests requiring use of only ITDs is that any change in lateralization ability or BILDs must be because of temporal factors.

In the binaural unmasking experiments, there was a nonzero BILD at NF = 1 for both babble and speech-shaped noise. As with lateralization, we expect that this small but positive BILD was because of sensitivity to envelope ITDs. The noise backgrounds were, however, the same in all cases, so in the condition in which the signal was delayed, bilaterally, there could be an extra 700-μs bit of signal information available to the listeners in the temporal gaps, which could contribute to the observed binaural advantage. We expect this was not a contributor to the BILD for NF = 1 for two reasons: (1) the duration of extra signal information was one to two orders of magnitude less than the duration of the gaps (∼30–70 ms), and (2) the results suggested listening in the gaps was a learned skill, and no evidence was found of learning the BILD. Thus, we believe these nonzero BILDs at NF = 1 were because of sensitivity to the envelope ITDs.

The presence of temporal fine structure greatly enhanced the ability of the listeners to take advantage of ITD cues when identifying speech in a steady-state background, but fine structure had little effect on the BILD in the babble background (Figs. 6 and 7). The babble had brief silent periods, which alone would not yield any binaural advantage, but could yield a unilateral advantage. There cannot be binaural unmasking in periods in which there is no masking. Thus, when ITD = 0 μs, the system appears to make maximum use of timing information unilaterally, such that the system could glean little additional benefit from bilateral interaural timing difference.

The present study compared SRTs between steady-state background and babble in which the babble was the same on every trial. The purpose of using the same noise background was to maintain consistency in the difficulty of the background noise. Trial-to-trial changes in the background noises would add a source of variance to the measurement of the SRT that was undesirable. With the babble background, however, listeners could learn to listen in the gaps. In the high NF condition in babble, there was about 6 dB of improvement, on average, in SRT over time.

The NF = 1 condition was similar to previous studies (Qin and Oxenham 2003; Stickney et al. 2004), which used multichannel, noise-excited vocoders, with no binaural cues. Qin and Oxenham demonstrated that SRTs were better for steady noise than for the single-talker background noise, and Stickney et al. demonstrated similar, and sometimes better performance with the steady background. Our study showed slightly better performance (although not significant) for the babble background than for steady-state background. The use of the same background noise on each trial could account for the differences, as these two previous studies used a speech masker, which differed on each trial. Also, we used two-talker babble, whereas Qin and Oxenham and Stickney et al. used one-talker background noise. The number of talkers can have a big effect on the extent of masking (Miller 1947). In addition, our listeners used a closed set speech test whereas the other studies used open set. Finally, our study used a Hilbert vocoder, but the other studies used a rectification-and-low-pass-filter approach. All of these factors could contribute to differences among studies.

The results suggested that improved delivery of temporal fine structure using a cochlear implant could improve the ability of implantees to localize by providing improved ITD encoding, and improve the ability of implantees to segregate speech from noise. Implantees have previously been shown to have more difficulty understanding spondees in babble versus steady backgrounds (Turner et al. 2004), but our recent (unpublished) results with 20 implant listeners have shown SRTs in babble and steady-state noise are about the same (mean SRT in babble −5.6 dB and mean SRT in steady-state, speech-shaped noise −6.6 dB). The best performance for an implantee in steady noise was −15 dB, corresponding to normal-hearing performance in Figure 5 at NF equal to about 0.85. This suggests that in steady noise better implant users receive some fine-structure information. Improvement in the delivery of fine-structure information would be expected to enhance performance.

Rubinstein et al. (1999) has proposed an approach for improving temporal encoding, which was shown neurophysiologically to yield responses that more closely resemble normal-hearing than those generated from traditional processing schemes (Litvak et al. 2003). The procedures described herein could be useful in evaluating strategies for improving temporal delivery in any cochlear implant device.

References

Assmann PF, Summerfield Q. Modeling the perception of concurrent vowels: vowels with different fundamental frequencies. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 88:680–697, 1990.

Best V, Schaik Av, Carlile S. Separation of concurrent broadband sound sources by human listeners. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115:324–336, 2004.

Bilger RC, Nuetzel JM, Rabinowitz WM, Rzeczkowski C. Standardization of a test of speech perception in noise. J. Speech Hear. Res. 27:32–48, 1984.

Bird J, Darwin CJ. Effects of a difference in fundamental frequency in separating two sentences. In: Palmer AR, Rees A, Summerfield AQ and Meddis R (eds) Psychophysical and Physiological Advances in Hearing. London, Whurr, pp. 263–269, 1998.

Brokx JPL, Nooteboom SG. Intonation and the perceptual separation of simultaneous voices. J. Phon. 10:23–36, 1982.

Bronkhorst AW, Plomp R. The effect of head-induced interaural time and level differences on speech intelligibility in noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 83:1508–1516, 1988.

Carhart R, Tillman TW, Johnson KR. Release of masking for speech through interaural time delay. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 42:124–138, 1967.

Culling JF, Darwin CJ. Perceptual separation of simultaneous vowels: within and across-formant grouping by F0. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 93:3454–3467, 1993.

Culling JF, Hawley ML, Litovsky RY. The role of head-induced interaural time and level differences in the speech reception threshold for multiple interfering sound sources. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116:1057–1065, 2004.

Dorman MF, Loizou PC, Fitzke J, Tu Z. The recognition of sentences in noise by normal-hearing listeners using simulations of cochlear-implant signal processors with 6–20 channels. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 104:3583–3585, 1998.

Drennan WR, Gatehouse S, Lever C. Perceptual segregation of competing speech sounds: the role of spatial location. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114:2178–2189, 2003.

Fishman K, Shannon RV, Slattery WH. Speech recognition as a function of the number of electrodes used in the SPEAK cochlear implant speech processor. J. Speech Hear. Res. 32:524–535, 1997.

Friesen LM, Shannon RV, Baskent D, Wang X. Speech recognition in noise as a function of the number of spectral channels: comparison of acoustic hearing and cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 110:1150–1163, 2001.

Good MD, Gilkey RH. Sound localization in noise. The effect of signal-to-noise ratio. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 99:1108–1117, 1996.

Harris RW. Speech audiometry materials compact disk. Provo, UT, Brigham Young University, pp. 1991.

Henning GB. Detectability of interaural delay in high-frequency complex waveforms. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 55:1974.

Houtsma AJM, Smurzynski J. Pitch identification and discrimination for complex tones with many harmonics. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 87:304–310, 1990.

Jeffress LA. A place theory of sound localization. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 41:35–39, 1948.

Jeffress LA. Medial geniculate body—a disavowal. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 30:802–803, 1958.

Jeffress LA, Blodgett HC, Deatherage BH. Effect of interaural correlation on the precision of centering a noise. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 34:1122–1123, 1962.

Klumpp RG, Eady HR. Some measurements of interaural time difference thresholds. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 28:859–860, 1956.

Kong Y-Y, Stickney GS, Zeng F-G. Speech and melody recognition in binaurally combined acoustic and electric hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 117:1351–1361, 2005.

Laback B, Pok S-M, Baumgartner W-D, Deutsch WA, Schmid K. Sensitivity to interaural level and envelope differences of two bilateral cochlear implant listeners using clinical sound processors. Ear Hear. 25:488–500, 2004.

Litvak L, Delgutte B, Eddington D. Improved neural representation of vowels in electric stimulation using desynchronizing pulse trains. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114:2099–2111, 2003.

Long CJ, Carlyon RP, Litovsky RY, Downs DH. Binaural unmasking with bilateral cochlear implants. J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 7:352–360, 2006.

Long CJ, Eddington DK, Colburn HS, Rabinowitz WM. Binaural sensitivity as a function of interaural electrode position with a bilateral cochlear implant user. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114:1565–1574, 2003.

McFadden D, Pasanen EG. Lateralization at high frequencies based on interaural time differences. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 59:634–639, 1976.

Meddis R, O’Mard L. A unitary model of pitch perception. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 102:1811–1820, 1997.

Miller GA. The masking of speech. Psychol. Bull. 44:105–129, 1947.

Plomp R. Pitch of complex tones. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 41:1526–1533, 1967.

Qin MK, Oxenham AJ. Effects of simulated cochlear-implant processing on speech reception in fluctuating maskers. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114:446–454, 2003.

Qin MK, Oxenham AJ. Effects of envelope-vocoder processing on F0 discrimination and concurrent-vowel identification. Ear Hear. 26:451–460, 2005.

Qin MK, Oxenham AJ. Effects of introducing unprocessed low-frequency information on the reception of envelope-vocoder processed speech. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 119:2417–2426, 2006.

Rayleigh L. On our perception of sound direction. Philos. Mag. 74:214–231, 1907.

Rubinstein JT, Turner CW. A novel acoustic simulation of cochlear implant hearing: effects of temporal fine structure. First International IEEE EMBS Conference on Neural Engineering, IEEE Press, 142–145, 2003.

Rubinstein JT, Wilson BS, Finley CC, Abbas PJ. Pseudospontaneous activity: stochastic independence of auditory nerve fibers with electrical stimulation. Hear. Res. 127:108–118, 1999.

Shannon RV, Zeng F-G, Kamath V, Wygonski J, Ekelid M. Speech recognition with primarily temporal cues. Science 270:303–304, 1995.

Smith ZM, Delgutte B, Oxenham AJ. Chimaeric sounds reveal dichotomies in auditory perception. Nature 416:87–90, 2002.

Stickney GS, Zeng F-G, Litovsky R, Assmann P. Cochlear implant speech recognition with speech maskers. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116:1081–1091, 2004.

Tobias JV, Schubert ED. Effective onset duration of auditory stimuli. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 31:1595–1605, 1959.

Turner CW, Gantz BJ, Vidal C, Behrens A, Henry BA. Speech recognition in noise for cochlear implant listeners: Benefits of residual acoustic hearing. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 115:1729–1735, 2004.

Van de Par S, Kohlrausch A. A new approach to comparing binaural masking level differences at low and high frequencies. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 101:1671–1680, 1997.

Van Hoesel RJM, Tyler RS. Speech perception, localization and lateralization with bilateral cochlear implants. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 113:1617–1630, 2003.

Wightman FL, Kistler DJ. The dominant role of low frequency interaural time differences in sound localization. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 91:1648–1661, 1992.

Won JH, Drennan W, Rubinstein J. Spectral ripple resolution and speech perception in babble and speech-shaped noise by cochlear implant listeners. Presented at the 30th annual midwinter meeting of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology, vol. 30, pp. 304, 2007.

Xu L, Pfingst BE. Relative importance of temporal envelope and fine structure in lexical-tone perception. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 114:3024–3027, 2003.

Yost WA, Wightman FL, Green DM. Lateralization of filtered clicks. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 39:1526–1531, 1971.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the dedicated efforts of our listeners. We thank Chad Ruffin for assistance in the creation of Figure 1. Leah Drennan and two anonymous reviewers provided helpful comments on previous versions of this manuscript. JHW appreciates the mentorship of SM Lee and SH Hong. This work was supported by NIH grants R01-DC007525, a subcontract of P50-DC00242, T32-DC00018 (VKD), the University of Washington, and grants from the Korean Science and Engineering Foundation, and Hanyang University (JHW).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drennan, W.R., Won, J.H., Dasika, V.K. et al. Effects of Temporal Fine Structure on the Lateralization of Speech and on Speech Understanding in Noise. JARO 8, 373–383 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-007-0074-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10162-007-0074-y