Abstract

Background

Endoscopic resection is performed in undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer (UD-EGC), including poorly differentiated (PD) adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell (SRC) carcinoma. We previously found that different approaches are needed for PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma for curative resection. However, according to the 2010 WHO classification, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma are categorized in the “poorly cohesive carcinomas.” Thus, we assessed whether the WHO classification is helpful when endoscopic resection is performed for treatment of UD-EGC.

Methods

We analyzed clinicopathological features of 1295 lesions with SRC carcinoma and PD adenocarcinoma treated by open surgery. We recategorized them into intestinal-type PD adenocarcinomas and poorly cohesive carcinomas (SRC carcinoma, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma). We also recategorized 176 lesions treated by endoscopic resection into intestinal-type PD adenocarcinomas and poorly cohesive carcinomas.

Results

According to the open surgery data, the rates of lymph node metastasis (LNM) and lymphovascular invasion were significantly lower in SRC carcinoma than in diffuse-type and intestinal-type PD adenocarcinomas. The rates of LNM and lymphovascular invasion were significantly higher in diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma than in SRC carcinoma. Endoscopic resection data showed no recurrence if the carcinoma was curatively resected. However, the commonest cause of noncurative resection was different in SRC carcinoma and PD adenocarcinoma. A positive lateral margin was the commonest cause in SRC carcinoma versus a positive vertical margin in both intestinal-type and diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

The clinical behavior differs in diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma. On the basis of LNM and outcomes of endoscopic resection, the recent WHO classification may not be helpful when endoscopic resection is performed for treatment of UD-EGC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The standard treatment for early gastric cancer (EGC) has been open surgery. However, endoscopic resection became a standard local treatment for some EGC cases without lymph node metastasis (LNM) [1]. Initially, endoscopic resection was applied primarily to EGC cases that were differentiated, with a size of less than 2 cm, and present only in the mucosa [2–4]. Now, the indications for endoscopic resection have been expanded through many studies. The expanded criteria for endoscopic resection even include cases of EGC of undifferentiated histological type (undifferentiated-type EGC, UD-EGC), such as mucosal cancer smaller than 2 cm with no ulcers [5]. Many studies have reported on the feasibility and effectiveness of endoscopic resection for treatment of UD-EGC [6–9]. According to a study from our institution on the long-term follow-up outcomes of endoscopic resection for treatment of UD-EGC, there was no recurrence during the follow-up period if curative resection had been performed after endoscopic resection. When UD-EGC was divided into poorly differentiated (PD) adenocarcinoma and signet ring cell (SRC) carcinoma, noncurative resection occurred in PD adenocarcinoma, because of it being vertical margin positive, and in SRC carcinoma, because of it being lateral margin positive. To achieve curative resection in UD-EGC, the study suggested that a different approach may be needed because of the different characteristics of PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma [6, 10].

The Japanese classification, a commonly used histological classification for endoscopic resection today, separates EGC into differentiated and undifferentiated types [11]. The previously used WHO histological classification included both PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma in UD-EGC. PD adenocarcinoma is classified into intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma and diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, on the basis of the Lauren classification. However, according to the recently published 2010 WHO classification on stomach cancer, both diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma are classified in the same category, as poorly cohesive carcinomas, whereas intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma is classified separately [12]. The definitions of intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, and SRC carcinoma are as follows: intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma displays a solid sheetlike proliferation with an alveolar pattern and indistinct tubular differentiation; diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma is acinar, trabecular, or consists of separate cells or clusters of a few cells with diffuse infiltration; SRC carcinoma is a unique subtype of mucin-producing adenocarcinoma characterized by abundant intracellular mucin accumulation and a compressed nucleus displaced toward one extremity of the cell.

We sought to determine whether it is clinically appropriate to classify diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma in the same category, as poorly cohesive carcinomas, from a biological behavior viewpoint. We thus assessed whether the 2010 WHO classification is helpful when endoscopic resection is performed for treatment of UD-EGC.

Patients and methods

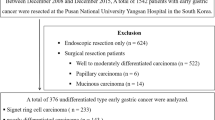

We studied 1338 patients with UD-EGC who underwent open surgery and 209 patients with UD-EGC who underwent endoscopic resection at Gangnam Severance Hospital from January 2005 to December 2012.

We performed a retrospective study and assessed two groups. First, to analyze the biological behavior of poorly cohesive carcinomas, we assessed a group of patients with UD-EGC who underwent open surgery. Second, to assess the usefulness of the new WHO classification for endoscopic resection, we evaluated UD-EGC patients who underwent endoscopic resection. Among the 1338 UD-EGC patients who underwent open surgery, we selected 1295 patients who had intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma and poorly cohesive carcinoma on the basis of the 2010 WHO classification. Of the 209 UD-EGC patients who underwent endoscopic resection, we selected 176 patients with intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma and poorly cohesive carcinoma. We analyzed the selected EGC using the WHO, Japanese, and Lauren histological classification methods.

The 2010 WHO histological classification recognizes four major histological patterns: tubular, papillary, mucinous, and poorly cohesive (including SRC carcinoma) [12]. In the Japanese classification system, well and moderately differentiated tubular adenocarcinoma and papillary adenocarcinoma are classified as differentiated type, and PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma are classified as undifferentiated type [11, 13]. In the Lauren classification system, intestinal-type and diffuse-type adenocarcinomas are the two major histological subtypes [14].

Tumor locations were categorized by the longitudinal axis and cross-sectional circumference of the stomach. The longitudinal axis of the stomach was divided into three sections: the upper third, containing the fundus, cardia, and upper body; the middle third, containing the middle body, lower body, and angle; and the lower third, containing the antrum and pylorus. The cross-sectional circumference was divided into four areas: lesser curvature, posterior wall, greater curvature, and anterior wall. Endoscopic findings of the tumors were classified by predominant type according to the classification system of the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer. The protruded type and superficial elevated type were classified as elevated type. The superficial flat type was classified as flat type. On the basis of a previous study, the superficial depressed type and the excavated type were classified as depressed type [15]. The Institutional Review Board of Gangnam Severance Hospital approved this study.

Statistical analysis

The χ 2 test was used to examine associations among categorical variables, and the t test was used for noncategorical variables. A p value less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. All analyses were performed with SPSS (version 18.0 for Windows; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics of patients with UD-EGC

The clinical characteristics of UD-EGC patients in the present study are shown in Table 1. We analyzed the intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, and SRC carcinoma patients, noting the following characteristics. SRC carcinoma patients were significantly younger, included more females, and had more lesions of flat type in gross appearance than the intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma and diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma patients. Among patients who underwent endoscopic resection, SRC carcinoma patients were younger and included more females than the other two groups. There was no significant difference in the location of the cancer in all three groups in those who underwent open surgery or endoscopic resection.

Comparisons among UD-EGC in terms of the biological behavior in open surgery data

The biological behavior, including LNM, was analyzed according to the histological types of UD-EGC in the patients who underwent open surgery (Table 2). The rate of LNM was 15.8 % in intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma, 13.5 % in diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, and 6.3 % in SRC carcinoma, with the rate being significantly lower in SRC carcinoma. Positivity of lymphovascular invasion (LVI) showed results similar to LNM. LVI was also observed to be significantly lower in SRC carcinoma versus the other two groups. There was no significant difference in perineural invasion among the groups. For the depth of invasion, there was a significantly greater rate of mucosa-confined lesions in SRC carcinoma than in intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma or diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma. However, within the expanded criteria for endoscopic resection, there was no LNM in any group (Table 3).

Comparison among UD-EGC in terms of therapeutic outcomes of endoscopic resection

We then assessed the 176 patients with UD-EGC who underwent endoscopic resection. Of these patients, 34 (19.3 %) had intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma, 23 (13.1 %) had diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, and 119 (67.6 %) had SRC carcinoma. In all intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, and SRC carcinoma patients, there was no cancer recurrence during the follow-up period (30.6 ± 19.5 months) if curative resection was achieved through endoscopic resection. Overall long-term clinical outcomes after endoscopic resection are summarized in Fig. 1.

Clinical courses after endoscopic resection (ER) for early gastric cancer of undifferentiated histological type. The numbers in the boxes indicate the number of cases. APC argon plasma coagulation, CR curative resection, CTx, Op open surgery, PD poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, Recur recurrence, SRC signet ring cell carcinoma

Table 4 shows the therapeutic outcomes after endoscopic resection in UD-EGC. There was no significant difference in the success rate of en bloc resection and curative resection among the three groups. However, the causes of noncurative resection did differ significantly. In both intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma and diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma, vertical margin positivity was the commonest cause of noncurative resection, whereas lateral margin positivity was the commonest cause of noncurative resection in SRC carcinoma.

Discussion

The indication for endoscopic resection has been expanding as a standard local treatment for selective EGC [5]. Today, the indication for endoscopic resection is decided by classification of EGC into differentiated and undifferentiated types on the basis of the Japanese classification. According to the previous WHO classification, the undifferentiated type included SRC carcinoma and PD adenocarcinoma. PD adenocarcinoma can be classified into diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma on the basis of the Lauren classification. The 2010 WHO classification categorizes both diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma in the same group as poorly cohesive carcinomas [12].

On the basis of our previous reports, the long-term outcomes of endoscopic resection did not differ between PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma; however, the main cause of noncurative resection was different between PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma. Thus, we investigated whether the recent WHO histological classification could be helpful when endoscopic resection is performed for treatment of UD-EGC [6, 10]. To the best of our knowledge, the work reported here is the first investigating clinical behavior in EGC on the basis of the recent WHO histological classification.

The recent WHO classification for gastric cancer was based on morphological patterns and did not consider histogenesis, differentiation, or epidemiological data to achieve harmonization of the histological typing of gastrointestinal tract carcinoma [16]. However, according to our data, the clinical behavior differs between diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma, which are both categorized as poorly cohesive carcinomas.

According to the gastrectomy cases, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma, which are both categorized as poorly cohesive carcinomas, showed different clinical behavior. Diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma showed a higher rate of LNM and LVI than SRC carcinoma, similarly to intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma. The rate of submucosal invasion was higher in diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma than in SRC carcinoma. When endoscopic resection is applied in EGC, biological behavior, such as LNM, LVI, and depth of invasion, is important. However, the types of behavior were quite different between diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma, which are both categorized as poorly cohesive carcinomas in the 2010 WHO classification system. Indeed, diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma shows biological behavior more similar to intestinal-type PD adenocarcinoma than to SRC carcinoma.

Previous studies have shown that SRC carcinoma in the stomach significantly differs from gastric adenocarcinoma [17, 18]. Gene expression data also showed that SRC carcinoma may be a completely distinct entity [17, 18]. Furthermore, Konno-Shimizu et al. [19] found that cathepsin E (CTSE) is a marker for SRC carcinoma of the stomach. CTSE showed different expression between SRC carcinoma and PD adenocarcinoma [19]. Gastric SRC carcinoma showed distinctive gene expression, such as high expression of CTSE and MUC5AC but low expression of MUC2 in both tumors and background mucosa [19]. These findings suggest that gastric SRC carcinoma may be different from PD adenocarcinoma.

When analyzing LNM within the expanded criteria of endoscopic resection, we found that no UD-EGC showed any LNM. That is, there was no additional information from the recent WHO histological classification in UD-EGC. Furthermore, considering the outcomes of endoscopic resection, the recent WHO histological classification was less informative than the previous WHO classification in UD-EGC. That is, the long-term outcome of no cancer recurrence was the same for all three groups if curative resection was achieved. Thus, the current criteria for endoscopic resection may be sufficient to decide on the feasibility and curability of endoscopic resection in UD-EGC. However, similarly to the study results previously published by our institution, the causes of noncurative resection did differ between SRC carcinoma and PD adenocarcinoma (both intestinal type and diffuse type). The causes of noncurative resection were also different between patients with diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and patients with SRC carcinoma, which are both categorized in the same group, as poorly cohesive carcinomas. Thus, the recent WHO classification system is not helpful for clinical outcomes after endoscopic resection . Instead, to prevent noncurative resection during endoscopic resection, we can apply the previous WHO classification system, which separated PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma. That is, the previous WHO classification system may be helpful to prevent noncurative resection during endoscopic resection among the current histological classifications of gastric cancer. Because our study analyzed only clinical behavior in UD-EGC, further studies may be needed to assess the clinical significance of the WHO histological classification for stomach cancer.

This study had a limitation in terms of its retrospective design, and could not demonstrate all significant factors in all of the subjects.

In conclusion, the clinical behavior differs between diffuse-type PD adenocarcinoma and SRC carcinoma, which are both categorized as poorly cohesive carcinomas under the WHO classification. For LNM and outcomes of endoscopic resection, the recent WHO classification may not be helpful when endoscopic resection is performed for treatment of UD-EGC.

References

Goto O, Fujishiro M, Kodashima S, Ono S, Omata M. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer with special reference to validation for curability criteria. Endoscopy. 2009;41:118–22.

Gotoda T, Yanagisawa A, Sasako M, Ono H, Nakanishi Y, Shimoda T, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis from early gastric cancer: estimation with a large number of cases at two large centers. Gastric Cancer. 2000;3:219–25.

Yamao T, Shirao K, Ono H, Kondo H, Saito D, Yamaguchi H, et al. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis from intramucosal gastric carcinoma. Cancer. 1996;77:602–6.

Kojima T, Parra-Blanco A, Takahashi H, Fujita R. Outcome of endoscopic mucosal resection for early gastric cancer: review of the Japanese literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:550–4.

Soetikno R, Kaltenbach T, Yeh R, Gotoda T. Endoscopic mucosal resection for early cancers of the upper gastrointestinal tract. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4490–8.

Kim JH, Kim YH, da Jung H, Jeon HH, Lee YC, Lee H, et al. Follow-up outcomes of endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer with undifferentiated histology. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:2627–33.

Hirasawa T, Gotoda T, Miyata S, Kato Y, Shimoda T, Taniguchi H, et al. Incidence of lymph node metastasis and the feasibility of endoscopic resection for undifferentiated-type early gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2009;12:148–52.

Ahn JY, Jung HY, Choi KD, Choi JY, Kim MY, Lee JH, et al. Endoscopic and oncologic outcomes after endoscopic resection for early gastric cancer: 1370 cases of absolute and extended indications. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:485–93.

Lee H, Yun WK, Min BH, Lee JH, Rhee PL, Kim KM, et al. A feasibility study on the expanded indication for endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:1985–93.

Kim JH, Lee YC, Kim H, Song KH, Lee SK, Cheon JH, et al. Endoscopic resection for undifferentiated early gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:e1–9.

Lee HH, Song KY, Park CH, Jeon HM. Undifferentiated-type gastric adenocarcinoma: prognostic impact of three histological types. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:254.

Hu B, El Hajj N, Sittler S, Lammert N, Barnes R, Meloni-Ehrig A. Gastric cancer: classification, histology and application of molecular pathology. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2012;3:251–61.

Nakamura K, Sugano H, Takagi K. Carcinoma of the stomach in incipient phase: its histogenesis and histological appearances. Gan. 1968;59:251–8.

Lauren P. The two histological main types of gastric carcinoma: diffuse and so called intestinal-type carcinoma: an attempt at a histo-clinical classification. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand. 1965;64:31–49.

Akahoshi K, Chijiwa Y, Hamada S, Sasaki I, Nawata H, Kabemura T, et al. Pretreatment staging of endoscopically early gastric cancer with a 15 MHz ultrasound catheter probe. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:470–6.

Bosman FT, Carneiro F, Hruban RH, Theise ND. WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2010. p. 48–58.

Taghavi S, Jayarajan SN, Davey A, Willis AI. Prognostic significance of signet ring gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3493–8.

Shah MA, Khanin R, Tang L, Janjigian YY, Klimstra DS, Gerdes H, et al. Molecular classification of gastric cancer: a new paradigm. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2693–701.

Konno-Shimizu M, Yamamichi N, Inada K, Kageyama-Yahara N, Shiogama K, Takahashi Y, et al. Cathepsin E is a marker of gastric differentiation and signet-ring cell carcinoma of stomach: a novel suggestion on gastric tumorigenesis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e56766.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012R1A1A1042417).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human rights statement and informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent was impossible in this study because of the retrospective nature. However, only data from the patients were analyzed retrospectively, and information that would identify of patients was not included in this article.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, Y.H., Kim, JH., Kim, H. et al. Is the recent WHO histological classification for gastric cancer helpful for application to endoscopic resection?. Gastric Cancer 19, 869–875 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0538-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10120-015-0538-4