Abstract

During regulatory sampling of fathead minnows (Pimephales promelas), a novel calicivirus was isolated from homogenates of kidney and spleen inoculated into bluegill fry (BF-2) cells. Infected cell cultures exhibiting cytopathic effects were screened by PCR-based methods for selected fish viral pathogens. Illumina HiSeq next generation sequencing of the total RNA revealed a novel calicivirus genome that showed limited protein sequence similarity to known homologs in a BLASTp search. The complete genome of this fathead minnow calicivirus (FHMCV) is 6564 nt long, encoding a polyprotein of 2114 aa in length. The complete polyprotein shared only 21% identity with Atlantic salmon calicivirus,followed by 11% to 14% identity with mammalian caliciviruses. A molecular detection assay (RT-PCR) was designed from this sequence for screening of field samples for FHMCV in the future. This virus likely represents a prototype species of a novel genus in the family Caliciviridae, tentatively named “Minovirus”.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Caliciviruses are small non-enveloped viruses with icosahedral symmetry. They contain a positive sense, single-stranded, non-segmented RNA as their genome [1]. Caliciviruses can cause a wide variety of diseases in vertebrate hosts including humans, cats, pigs, rabbits, marine mammals, and fish [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Manifestations of disease resulting from calicivirus infections are broad and can include gastroenteritis, respiratory disease, vesicular lesions, abortion, encephalitis, myocarditis, hepatitis, hemorrhage, and death.

The family Caliciviridae consists of five genera: Lagovirus, Nebovirus, Norovirus, Sapovirus, and Vesivirus. The recent discovery of novel caliciviruses in non-human vertebrates, has resulted in proposals for the generation of several new genera, including “Nacovirus”, “Valovirus”, “Bavovirus”, Sanovirus”, Secalivirus” and “Recovirus” [1, 3, 7,8,9; http://www.caliciviridae.com/]. Recently, Mikalsen et al. [10] identified and characterized a novel Atlantic salmon calicivirus (ASCV) in Norway and proposed a new genus, “Salovirus”. Caliciviruses are often divided into two broad categories based on their general distribution in nature: (i) terrestrial caliciviruses, which are found in association with terrestrial host species only, and (ii) marine caliciviruses, which are found in marine-based host species but can also infect and cause disease in terrestrial hosts [1, 9,10,11].

Caliciviruses belong to a bigger “picorna-like virus” group that is thought to have evolved since eukaryogenesis [12]. Therefore, the presence of a prototypical calicivirus in fish was expected but was not confirmed until Mikalsen et al. [10] identified and characterized a novel virus, Atlantic salmon calicivirus (ASCV), in Norway. ASCV was isolated from heart tissue of salmon experiencing heart and skeletal muscle inflammation (HSMI), an emerging and sometimes fatal disease of farmed Atlantic salmon [10]. Current evidence suggests that HSMI is caused by a piscine orthoreovirus (PRV), which was also found retrospectively by PCR to be present in the heart samples from which ASCV was isolated. However, the role of PRV and ASCV in HSMI remains uncertain due to: (i) the lack of an established in vitro culture system for PRV that would be helpful in fulfilling Koch’s postulates, (ii) the absence of clinical signs in PRV-positive salmon populations [13, 14], and (iii) the absence of disease following experimental infection of Atlantic and sockeye salmon with a North American PRV isolate [15].

The size of the calicivirus genome varies from 6.4 kb to 8.5 kb [1], with two types of genomic organization. The first genomic organization type – found in members of the genera Norovirus, “Recovirus” and Vesivirus – is characterized by three open reading frames. ORF1 encodes a nonstructural polyprotein composed of helicase, protease and polymerase, ORF2 encodes the major capsid protein (VP1), and ORF3 encodes a minor capsid protein (VP2) with a putative nucleic acid binding function [1, 7, 8]. The second type of genomic organization – found in members of the genera Lagovirus, “Nacovirus”, Nebovirus, Sapovirus, and “Valovirus” – is characterized by the presence of only two ORFs. The nonstructural polyprotein and major capsid protein VP1 are encoded by the large ORF1, and the minor structural protein VP2 is encoded by the smaller ORF2 [1, 2, 9]. Genomic characterization of caliciviruses from all known genera indicates that the non-structural proteins are encoded by ORF1 and present in the same order in ORF1. Starting at the 5′-end of the genome, the genes encoding the following proteins are found in the order indicated: N-terminal protein (Nterm), NTPase, 3A-like protein, VPg, protease (Pro), and RNA polymerase (Pol). The structural proteins VP1 and VP2 are present in the 3′-terminus, and the 3′-terminus of the RNA is polyadenylated [1].

Baitfish are economically and ecologically important throughout the United States; there are 166 baitfish farms, which produced $29.37 million worth of baitfish in 2013 [16]. The fathead minnow (Pimephales promelas, order Cypriniformes, class Actinopterygii) is one of the most important baitfish species in the United States; fathead minnows produced at 100 farms contributed $9.88 million to the economy in 2013 [16]. In this study, we report on the isolation and genomic characterization of a novel calicivirus in fathead minnow, which is provisionally called “fathead minnow calicivirus” (FHMCV).

Materials and methods

Source of samples

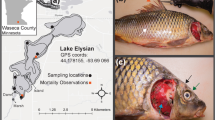

Several species of baitfish, including fathead minnows, were collected from four Wisconsin baitfish dealers by the La Crosse Fish Health Center (US Fish and Wildlife Service, Onalaska, WI) for mandatory inspection. Clinical signs of hemorrhages on skin, fin bases, and eyes were observed in some lots of fathead minnows (Fig. 1). Fish were shipped live and euthanized in the laboratory with an overdose of MS-222 (Argent Chemical Laboratories) and examined for gross abnormalities as described previously [17, 18]. Kidney and spleen were collected for subsequent virus isolation.

Virus isolation

Virus isolation was performed at the La Crosse Fish Health Center according to Blue Book policy (US Fish and Wildlife Service and American Fisheries Society – Fish Health Section) [17, 18]. Briefly, homogenates of kidney and spleen were inoculated onto three different cell lines (Epithelioma papulosum cyprini [EPC], Chinook salmon embryo [CHSE], and bluegill fry [BF-2]). The EPC cells were incubated at 15 °C and 20 °C, the CHSE cells at 15 °C, and the BF-2 cells at 25 °C. If no cytopathic effect (CPE) was seen after 14 days of incubation, the cell culture supernatants were blind passaged on fresh cells and observed for an additional 14 days. A total of 11 isolates exhibiting uncharacterized CPE, and testing negative by conventional PCR against a number of known target fish pathogens were submitted to the Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory (MVDL) for virus identification. At the MVDL, these 11 isolates were subcultured once more to confirm the CPE followed by additional procedures for virus identification and characterization.

Electron microscopy

Infected cell culture fluids were centrifuged at 2,900×g for 10 min and then at 30 PSI for 10 min in an Airfuge (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) for 10 min. The supernatant was discarded, and the pellets were resuspended in 10 µl of double-distilled water. The suspensions were placed on formvar-coated copper grids (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA) followed by staining with 1% phosphotungstic acid (Electron Microscopy Sciences) for 1 min. The grids were observed under a JEOL 1200 EX II transmission electron microscope (JEOL LTD, Tokyo, Japan), and the images were obtained using a Veleta 2K x2K camera with iTEM software (Olympus SIS, Munster, Germany).

Molecular testing

Fluids from infected cell cultures were centrifuged at 1,500×g for 15 min. The supernatant was subjected to nucleic acid extraction using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit and a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA), in parallel, followed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) at the La Crosse Fish Health Center and at the MVDL for the detection of common fish pathogens [17], viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus (VHSV), spring viremia of carp virus (SVCV), infectious pancreatic necrosis virus (IPNV), largemouth bass virus (LMBV), bluegill picornavirus (BGPV) [19], golden shiner virus (GSV; A. Goodwin, personal communication), fathead minnow nidovirus (FHMNV) [20], and fathead minnow picornavirus (FHMPV).

Illumina sequencing

Viral RNA was extracted from cell culture supernatants using TRIzol LS Reagent (Invitrogen, NY, USA) followed by RNA purification using a QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). RNA samples were then submitted to the University of Minnesota Genomics Center (UMGC) for cDNA synthesis, library preparation, and 50-bp single-end-reads sequencing using the Illumina HiSeq platform.

Sequence analysis and phylogeny

Nucleotide sequence data obtained from next-generation sequencing of the isolates were quality trimmed and assembled de novo in CLC Genomics Workbench 9.5 (https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com/products/clc-genomics-workbench/). The resulting contigs were then screened against an in-house virus database (unpublished novel fish RNA virus sequences archived in our laboratory) using Blastx with an E-value cutoff of <0.1, and the open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted using the NCBI ORF Finder tool (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). For phylogenetic analysis, the protein sequences of the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) and capsid protein were aligned using MAFFT [21] and concatenated using the Geneious (Biomatters) software package. The final dataset contained 1604 amino acid (aa) characters (including gaps). A maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE (http://iqtree.cibiv.univie.ac.at/) [22] with default parameters using 1,000 bootstrap replicates. Amino acid profiles and identity figures of complete ORF comparisons were generated by using Geneious Pro [23]. Sliding-window and pairwise comparisons were carried out using Sequence Demarcation Tool version 1.2 as described previously [24,25,26].

GenBank accession number

The genomic sequence of the new virus isolate was submitted to GenBank with accession number KX371097.

Development of a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) assay for the detection of FHMCV

Using the obtained sequence, primers FHMCV_RdRp_F (5′-TCAAGCGAAGCAGTATGTGG-3′) and FHMCV_RdRp_R (5′-ACCATGTTGGTAGGCCTCAG-3′) were designed targeting regions 3621-3641 and 4398-4418 of RdRp, generating an amplified product of 778 bp. A One Step RT-PCR Kit (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) was used for the PCR reaction. The specificity of the RT-PCR assay was evaluated by testing genomes of fathead minnow picornavirus (FHMPV), fathead minnow astrovirus, golden shiner picornavirus, golden shiner virus (GSV), and carp picornavirus. Archived samples (n = 11) from fathead minnows showing an unknown type of CPE were screened using this RT-PCR. Extracted RNA from uninfected cell cultures (EPC, CHSE and BF-2) was used as a negative control. The amplified PCR products were analyzed in a 1.0% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide (0.625 mg/ml). A single band of the expected product size confirmed the presence of target virus. Amplified products were purified using a QIAGEN PCR purification kit and then submitted to the UMGC for Sanger sequencing with forward and reverse primers, and the resulting sequences were aligned using Sequencher 5.1 software (www.genecodes.com) followed by BLAST analysis (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGE_TYPE=BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome).

Results

Virus isolation and morphological characterization

A novel calicivirus, provisionally called “fathead minnow calicivirus” (FHMCV), was isolated from the spleen and kidney tissue homogenate of a single fathead minnow in BF-2 cells incubated at 25 °C and in EPC cells incubated at 20 °C. In addition, a fathead minnow picornavirus (FHMPV) was also isolated in EPC cells [17]. In BF-2 cells, CPE was present from 7-12 days postinfection and was characterized by rounding and aggregation of cells (Fig. 2). The virus particles were spherical, featureless, and non-enveloped with a diameter of 30-32 nm when examined by negative contrast electron microscopy (Fig. 3).

Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis

The sequence contigs obtained by CLC de novo assembly from one of the isolates matched with members of the family Caliciviridae on BLASTx analysis. More than 34,000 reads were used to assemble this 6564-nt long sequence (Fig. 4). Partial 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) were 45 nt and 43 nt long, respectively. The genome contained two ORFs (ORF1 and ORF2) (Fig. 5A). ORF1 encoded a 2,114-aa-long polyprotein with a predicted molecular weight of 232.30 kDa and isoelectric point of 6.97. Amino acid motifs and/or nucleotide sequence analysis of ORF1 indicated the presence of conserved calicivirus protein motifs corresponding to both non-structural proteins (NS) and the major capsid protein (VP1). In addition, ORF1 included an NTPase/helicase motif GXPGXGK(T/S) at position 287–293, a protease motif G(D/Y)CGXP at position 987–992, and three RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp) motifs, GLPSG, YGDD and DYXXWDST (present as DFAAWDKS), at positions 1295-1299, 1338–1341, and 1242–1249, respectively (Fig. 5B; Supplementary Figure 1). ORF2, which encoded a 117-aa protein (from position 6168 to 6521), overlapped the stop codon of ORF1 by 222 nt with a +2 frameshift. The ORF1 and ORF2 of FHMCV were 243 aa and 7 aa shorter than ORF1 and ORF2 of ASCV (NC_024031), respectively (Table 1); 243 aa were absent from the 5′ end of FHMCV (Fig. 6A). The ORF2 of FHMCV overlapped the stop codon of ORF1 by 222 nt as compared to 178 nt in ASCV (NC_024031).

Schematic diagram of the genome organization of fathead minnow calicivirus (FHMCV). A) The nearly complete genome including the 5′ (45 nt) and 3′ (174 nt) untranslated regions. The FHMCV sequence contains two ORFs: the large ORF1 encodes 2114 aa from nt position 46 to 6390, and the second, small ORF2 encodes 117 aa from position 6168 to 6521. B) Conserved calicivirus protein motifs corresponding to both non-structural proteins (NS) and the major capsid protein (VP1) in ORF1

Genome comparisons of fathead minnow calicivirus (FHMCV). A) Sliding window analysis of the fish caliciviruses FHMCV and ASCV (Atlantic salmon calicivirus). Pairwise protein sequence identity of ORF1 was plotted using a window size of 45 amino acids. Below the sliding window analysis, identical loci are highlighted in black, and non-identical loci are highlighted in grey. B) Pairwise identity of the RdRp and VP1 regions of ORF1 from members of different genera in the family Caliciviridae

The most closely related virus to FHMCV is ASCV, yet their predicted ORF1 products shared less than 50% amino acid sequence protein identity (Fig. 6B), indicating that they belong to two separate viral genera. Notably, the FHMCV ORF1 is shorter than that of ASCV due to a reduction of sequence length at the N-terminus of the ORF1. The amino acid sequence identity of the FHMCV RdRp and capsid was low when compared to those of caliciviruses of other genera and ranged from 25-34% and 22-33%, respectively (Fig. 6B). Phylogenetic analysis based on the concatenated RdRp and capsid protein sequences produced a well-supported fish calicivirus clade that included the FHMCV and ASCV isolates (Fig. 7). The ORF2 sequence of FHMCV was highly divergent and did not match with those of previously reported caliciviruses or any other sequences in GenBank.

Phylogenetic tree of genomes of members of different genera of the family Caliciviridae, based on 1604 amino acids of concatenated polymerase and capsid proteins. The maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE with 1,000 bootstrap replicates. The study sequence is highlighted in red

RT-PCR

The RT-PCR assay developed in this study was specific for FHMCV and did not amplify any other fish pathogen. Two of the 11 isolates from fathead minnows showing an unknown type of CPE in EPC and BF-2 cells tested positive. Sequencing of the amplified product showed a 100% match to the HiSeq contig sequence. There was no RNA amplification from negative control cell lines.

Discussion

In this study, we isolated and characterized a novel calicivirus (FHMCV) from fathead minnows. High-throughput sequencing and genomic analysis of FHMCV indicated the presence of two ORFs (ORF1 and ORF2) in FHMCV, which is concordant with the genome organization of ASCV and the members of the genera Lagovirus, Nebovirus, and Sapovirus. Phylogenetic analysis of several representatives of the family Caliciviridae based on concatenated amino acid sequences of the RdRp and capsid proteins of ORF1 provided strong evidence for the formation of a fish-specific calicivirus clade, which includes all known ASCV and FHMCV strains.

In addition, we developed a specific RT-PCR assay for screening of apparently healthy baitfish and other wild and farmed fish species for FHMCV. Virus-specific RT-PCR confirmed the presence of FHMCV in BF-2 and EPC cells. Because of the co-infection detected in EPC cells, it is difficult to determine whether one or both of the viruses caused the observed CPE. It should be noted that Mikalsen et al. [10] saw ASCV-induced CPE only after 34 weeks, requiring 15 blind passages in the grouper fin-1 (GF-1) cell line.

Recent studies have reported co-infection of ASCV with other viruses, such as PRV, PMCV, and SAV (viruses associated with myocarditis in Atlantic salmon) [10, 27]. Wiik-Nielsen et al. [27] studied a possible correlation of ASCV with PRV, PMCV and SAV in myocarditis cases by comparing viral loads (cycle threshold; ct values) but did not find any. This led them to speculate that there may be a negative correlation between ASCV viral load and HSMI. It remains possible that ASCV infection is related to myocardial disease. This warrants further pathogenicity studies to investigate whether FHMCV is linked to any known or emerging disease in baitfish.

Mikalsen et al. [10] sequenced two genetically distinct strains of ASCV from Atlantic salmon. The first of these, the ‘cell culture isolate’ (strain AL V901), was recovered from cell culture after more than 15 passages in GF-1 cells inoculated with heart tissue homogenates from salmon exhibiting signs of HSMI. The second strain, the ‘field strain’ (Nordland/2011), was cloned directly from the head kidney of salmon suffering from cardiomyopathy syndrome (CMS). The cell culture isolate strain was shorter than the field strain due to deletions located in the 5′ and 3′ UTRs and in both ORFs. None of these deletions, however, are present in motifs that are conserved throughout the family Caliciviridae.

The FHMCV genome sequence described here contains two ORFs (ORF1 and ORF2), similar to ASCV. However, both ORFs are shorter than those in ASCV strains [10]. ORF1 from FHMCV is 243 aa shorter than that of the ASCV field strain, specifically due to the absence of the sequence at the 5′ end of ORF1 in FHMCV. The absence of any homology in the ORF2 sequence and the high divergence of ORF1 indicate that this virus may have gone through recombinant events. Further studies should be conducted to detect the presence of this virus or related viruses in different lakes in Minnesota as well as in other fish species.

It is believed that biological diversity among viruses may be due to many mechanisms, such as incorporation of genetic material from the host, recombination between viruses belonging to the same or to a different family, and even recombination between viruses normally infecting different hosts [28]. The host immune system is also thought to play an important role in the emergence of pandemic norovirus strains through both antigenic drift and shift. The replacement of dominant circulating norovirus strains occurs approximately every 3 years due to antigenic drift and shift, and these new variants can re-infect hosts previously infected with earlier viruses [29]. The presence of recombinant human sapelovirus was correlated with the prevalence of sapelovirus in water samples (wastewater, treated wastewater and river water) and in shellfish used for human consumption [30]. Lakes have a complex environment due to their direct and indirect connections with animals, birds, humans and plants and hence may provide a suitable environment for the evolution of caliciviruses through recombination.

Despite the phylogenetic proximity of FHMCV and ASCV, conservation of the RdRp and capsid protein was relatively low, at 34% and 33%, respectively. The amino acid sequence identity in the RdRp gene between FHMCV and caliciviruses from other genera ranged between 25% and 28%. There are no clearly defined criteria for assigning genus and species names in the family Caliciviridae; however, a proposal of dual nomenclature using both ORF1 and VP1 sequences has been made because recombination is common among these viruses, and recognition of recombinants may be relevant [31]. Considering this new proposed criterion and the range of inter-genus sequence identity (Such as Vesivirus vs. Sapovirus, or Norovirus vs. Nebovirus; Fig. 6B) among FHMCV and other calicivirus, we propose that FHMCV is a prototype virus in a novel genus, tentatively called “Minovirus”. A proposal for the new genus will be submitted to the Executive Committee of the ICTV.

Further studies will be required to address the potential pathogenicity and species-susceptibility of FHMCV. An interesting outcome of this study is that fish with dual infection (FHMCV and FHMPV) showed clinical disease, making it necessary to continue screening diseased fish for both pathogens. Additionally, fish should be observed for subtle indications of disease, such as reduced feed intake, lethargy, and histopathological lesions. Further studies investigating the potential pathogenicity and species specificity of FHMCV are recommended because of the importance of fathead minnows to the baitfish industry, the phylogenetic proximity of FHMCV and ASCV, the preliminary data suggestive of ASCV’s pathogenicity in Atlantic salmon [10], and the uncertainty surrounding the etiological basis of HSMI in Atlantic salmon.

References

Clarke IN, Estes MK, Green KY, Hansman GS, Knowles NJ, Koopmans MK, Matson DO, Meyers G, Neill JD, Radford A, Smith AW, Studdert MJ, Thiel H-J, Vinjé J (2012) In: King AMQ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB, Lefkowitz EJ, Walham (eds) Caliciviridae, Virus taxonomy: the classification and nomenclature of viruses. The ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Academic Press, London, UK, pp 977–986

Wolf S, Reetz J, Hoffmann K, Grundel A, Schwarz BA (2012) Discovery and genetic characterization of novel caliciviruses in German and Dutch poultry. Arch Virol 157:1499–1507

Wolf S, Reetz J, Otto P (2011) Genetic characterization of a novel calicivirus from a chicken. Arch Virol 156:1143–1150

Wolf S, Williamson W, Hewitt J, Lin S, Rivera-Aban M (2009) Molecular detection of norovirus in sheep and pigs in New Zealand farms. Vet Microbiol 133:184–189

Tse H, Chan WM, Li KS, Lau SK, Woo PC (2012) Discovery and genomic characterization of a novel bat sapovirus with unusual genomic features and phylogenetic position. PLoS One 7:e34987

Thiel HJ, Konig M (1999) Caliciviruses: an overview. Vet Microbiol 69:55–62

Farkas T, Sestak K, Wei C, Jiang X (2008) Characterization of a rhesus monkey calicivirus representing a new genus of Caliciviridae. J Virol 82:5408–5416

L’Homme Y, Sansregret R, Plante-Fortier E, Lamontagne AM, Ouardani M, Lacroix G, Simard C (2009) Genomic characterization of swine caliciviruses representing a new genus of Caliciviridae. Virus Genes 39:66–75

Liao Q, Wang X, Wang D, Zhang D (2014) Complete genome sequence of a novel calicivirus from a goose. Arch Virol 159:2529–2531

Mikalsen AB, Nilsen P, Frøystad-Saugen M, Lindmo K, Eliassen TM (2014) Characterization of a Novel Calicivirus Causing Systemic Infection in Atlantic Salmon (Salmo salar L.): Proposal for a New Genus of Caliciviridae. PLoS One 9(9):e107132

Smith AW, Skilling DE, Cherry N, Mead JH, Matson DO (1998) Calicivirus emergence from ocean reservoirs: zoonotic and interspecies movements. Emerg Infect Dis 4:13–20

Koonin EV, Wolf YI, Nagasaki K, Dolja VV (2008) The Big Bang of picorna-like virus evolution antedates the radiation of eukaryotic super groups. Nat Rev Microbiol 6(12):925–939

Garseth AH, Biering E, Aunsmo A (2013) Associations between piscine reovirus infection and life history traits in wild-caught Atlantic salmon Salmo salar L. in Norway. Prev Vet Med 112:138–146

Løvoll M, Alarcon M, Bang JB, Taksdal T, Kristoffersen AB, Tengs T (2012) Quantification of piscine reovirus (PRV) at different stages of Atlantic salmon Salmo salar production. Dis Aquat Organ 99:7–12

Garver KA, Johnson SC, Polinski MP, Bradshaw JC, Marty GD, Snyman HN, Morrison DB, Richard J (2016) Piscine orthoreovirus from Western North America Is Transmissible to Atlantic Salmon and Sockeye Salmon but fails to cause heart and skeletal muscle inflammation. PLoS One 11:e0146229

United States Department of Agriculture (2014) 2013 Census of Aquaculture, volume 3. Table 4, pp 8

Phelps NBD, Mor SK, Armien AG, Batts W, Goodwin AE, Hopper L, McCann R, Ng TFF, Puzach C, Waltzek T, Winton J, Goyal SM (2014) Isolation and molecular characterization of a novel picornavirus from baitfish in the USA. PLoS One 9:e87593

USFWS and AFS-FHS (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and American Fisheries Society-Fish Health Section) (2010) Standard procedures for aquatic animal health inspections. In: AFS-FHS, FHS blue book: suggested procedures for the detection and identification of certain finfish and shellfish pathogens, ed. Bethesda, Maryland: AFS-FHS

Barbknecht M, Sepsenwol S, Leis E, Tuttle-Lau M, Gaikowski M, Knowles NJ, Lasee B, Hoffman HA (2014) Characterization of a new picornavirus isolated from the freshwater fish Lepomis macrochirus. J Gen Virol 95:601–613

Batts WN, Goodwin AE, Winton JR (2012) Genetic analysis of a novel nidovirus from fathead minnows. J Gen Virol 93:1247–1252

Katoh S (2013) MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol 30:772–780

Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ (2015) IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274

Drummond AJ, Ashton B, Buxton S, Cheung M, Cooper A (2011) Geneious v5.4. http://www.geneious.com Accessed 16 Oct 2013

Muhire BM, Varsani A, Martin DP (2014) SDT: a virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS One. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108277

Ng TFF, Marine R, Wang C, Simmonds P, Kapusinszky B, Bodhidatta L, Oderinde BS, Wommack KE, Delwart E (2012) High variety of known and new RNA and DNA viruses of diverse origins in untreated sewage. J Virol 86:12161–121751

Ng TF, Wellehan JF, Coleman JK, Kondov NO, Deng X, Waltzek TB, Reuter G, Knowles NJ, Delwart E (2015) A tortoise-infecting picornavirus expands the host range of the family Picornaviridae. Arch Virol 160:1319–1323

Wiik-Nielsen J, Alarcón M, Jensen BB, Haugland Ø, Mikalsen AB (2016) Viral co-infections in farmed Atlantic salmon, Salmo salar L., displaying myocarditis. J Fish Dis. doi:10.1111/jfd.12487

Davidson I, Silva RF (2008) Creation of diversity in the animal virus world by inter-species and intra-species recombinations: lessons learned from poultry viruses. Virus Genes 36(1):1–9

White PA (2014) Evolution of norovirus. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(8):741–745

Hansman GS, Oka T, Katayama K, Takeda N (2007) Human sapoviruses: genetic diversity, recombination, and classification. Rev Med Virol 17(2):133–141

Kroneman A, Vega E, Vennema H, Vinjé J, White PA, Hansman G, Green K, Martella V, Katayama K, Koopmans M (2013) Proposal for a unified norovirus nomenclature and genotyping. Arch Virol 158(10):2059–2068

Acknowledgements

We thank Wendy Wiese from the MVDL for technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

705_2017_3519_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Supplementary Figure 1 Sequence alignment of the RdRp gene of FHMCV with those of other caliciviruses. Amino acids highlighted in green are conserved motifs in RdRp. Amino acids highlighted in yellow are conserved in most of the sequences used in analysis (PDF 921 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mor, S.K., Phelps, N.B.D., Ng, T.F.F. et al. Genomic characterization of a novel calicivirus, FHMCV-2012, from baitfish in the USA. Arch Virol 162, 3619–3627 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3519-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00705-017-3519-6