Abstract

Ironic processing refers to the phenomenon where attempting to resist doing something results in a person doing that very thing. Here, we report three experiments investigating the role of ironic processing in visual search. In Experiment 1, we informed observers that they could predict the location of a salient color singleton in a visual search task and found that response times were slower in that condition than in a condition where the singleton’s location was random. Experiment 2 used the same experimental design but did not inform participants of the color singleton’s behavior. Experiment 3 showed that the cost in the predictable condition was not due to dual task costs or block order effects and participants attempting to use the strategy showed a larger cost in the predictable condition than those who abandoned using that location foreknowledge. In this case, responses in the predictable color singleton condition were equivalent with the random color singleton condition. This suggests that having more knowledge about an upcoming, salient distractor ironically increases its interfering influence on performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

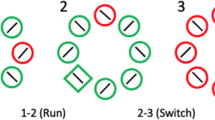

In the no additional singleton case, a switch is when all the display items changed color from the previous trial.

There was a marginal main effect of color repeat/switch, F(3,42) = 3.316, p = 0.090, \(\eta_{p}^{2}\) = 0.191, with mean RTs being 7 ms slower on switch compared to repeat trials, consistent with previous work (Becker, 2007).

Of course, this hypothesis also assumes that the effect is phenomenologically valid. In our experience of testing the experimental program, we found that this was case, though we have much more experience with these tasks than our participants do. Anecdotal conversations during participant debriefing, however, suggested that participants experienced the same costs.

Color repeat/switch main effect, F(3,42) = 2.599, p = 0.129, \(\eta_{p}^{2}\) = 0.157.

Thank you to an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

This is not say that there is no inhibitory component of spatial attention. A number of studies have reported evidence of inhibitory mechanisms (Gaspelin, Leonard, & Luck, 2015; 2017; Gaspar & McDonald, 2014; Sawaki & Luck, 2010). Our argument, however, is that these inhibitory mechanisms are not, at least within the given task, capable of being used intentionally. That is, the observers could not voluntarily inhibit an areas of space in advance of to-be-attended stimuli.

References

Arita, J. T., Carlisle, N. B., & Woodman, G. F. (2012). Templataes for rejection: Configuring attention to ignore task-irrelevant features. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 38, 580–584.

Asgeirsson, A. G., Kristjánsson, A., & Bundesen, C. (2014). Independent priming of location and color in identification of briefly presented letters. Attention, Perception & Psychophysics, 76, 40–48.

Awh, E., Belopolsky, A. V., & Theeuwes, J. (2012). Top-down versus bottom-up attentional control: A failed theoretical dichotomy. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 16, 437–443.

Beck, V. M., & Hollingworth, A. (2015). Evidence for negative feature guidance in visual search is explained by spatial recoding. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41, 1190–1196.

Becker, S. I. (2007). Irrelevant singletons in pop-out search: Attentional capture or filtering costs? Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 33, 764–787.

Becker, M. W., Hemsteger, S., & Peltier, C. (2016). No templates for rejection: A failure to configure attention to ignore task-irrelevant features. Visual Cognition, 6285, 1–18.

Belopolsky, A. V., Schreij, D., & Theeuwes, J. (2010). What is top-down about contingent capture? Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 326–341.

Belopolsky, A. V., & Theeuwes, J. (2010). No capture outside the attentional window. Vision Research, 50, 2543–2550.

Belopolsky, A. V., Zwaan, L., Theeuwes, J., & Kramer, A. F. (2007). The size of an attentional window modulates attentional capture by color singletons. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 14, 934–938.

Bundesen, C., Vangkilde, S., & Petersen, A. (2015). Recent developments in a computational theory of visual attention (TVA). Vision Research, 116, 210–218.

Cave, K. R. (1999). The FeatureGate model of visual selection. Psychological Research, 62, 182–194.

Cepeda, N. J., Cave, K. R., Bichot, N. P., & Kim, M. S. (1998). Spatial selection via feature-driven inhibition of distractor locations. Perception & Psychophysics, 60, 727–746.

Chao, H.-F. (2010). Top-down attentional control for distractor locations: The benefit of precuing distractor locations on target localization and discrimination. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 36, 303–316.

Chelazzi, L., Miller, E. K., Duncan, J., & Desiomne, R. (1993). A neural basis for visual search in inferior temporal cortex. Nature, 363, 339–342.

Chun, M. M., & Jiang, Y. (1998). Contextual cueing: Implicit learning and memory of visual context guides spatial attention. Cognitive Psychology, 36, 28–71.

Cohen, A., Ivry, R. I., & Keele, S. W. (1990). Attention and structure in sequence learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology. Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16, 17–30.

Cousineau, D. (2005). Confidence intervals in within-subject designs: A simpler solution to Loftus and Masson’s method. Tutorials in quantitative methods for psychology, 1, 42–45.

Destrebecqz, A., & Cleeremans, A. (2001). Can sequence learning be implicit? New evidence with the process dissociation procedure. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 8, 343–350.

Egner, T. (2008). Multiple conflict-driven control mechanisms in the human brain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 12, 374–380.

Eriksen, B. A., & Eriksen, C. W. (1974). Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target letter in a nonsearch task. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 16, 143–149.

Erskine, J. A., Georgiou, G. J., & Kvavilashvili, L. (2010). I suppress, therefore I smoke: Effects of thought suppression on smoking behavior. Psychological Science, 21, 1225–1230.

Gaspar, J. M., & McDonald, J. J. (2014). Suppression of salient objects prevents distraction in visual search. Journal of Neuroscience, 34, 5658–5666.

Gaspelin, N., Leonard, C. J., & Luck, S. J. (2015). Direct evidence for active suppression of salient-but-irrelevant sensory inputs. Psychological Science, 26, 1740–1750.

Gaspelin, N., Leonard, C. J., & Luck, S. J. (2017). Suppression of overt attentional capture by salient-but-irrelevant color singletons. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 79, 45–62.

Geyer, T., Zehetleitner, M., & Müller, H. J. (2010). Positional priming of pop-out: A relational-encoding account. Journal of Vision, 10, 1–17.

Gibson, B. S., & Bryant, T. A. (2008). The identity intrusion effect: Attentional capture or perceptual load? Visual Cognition, 16, 182–199.

Gokce, A., Müller, H. J., & Geyer, T. (2015). Positional priming of visual pop-out search is supported by multiple spatial reference frames. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 1–13.

Grafton, S. T., Hazeltine, E., & Ivry, R. (1995). Functional mapping of sequence learning in normal humans. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 7, 497–510.

Hasson, U., Chen, J., & Honey, C. J. (2015). Hierarchical process memory: Memory as an integral component of information processing. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19, 304–313.

Hillstrom, A. P. (2000). Repetition effects in visual search. Perception & Psychophysics, 62, 800–817.

Hommel, B., Pratt, J., Colzato, L., & Godijn, R. (2001). Symbolic control of visual attention. Psychological Science, 12, 360–365.

Jiang, Y., & Wagner, L. C. (2004). What is learned in spatial contextual cuing—configuration or individual locations? Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 66, 454–463.

Jollie, A., Ivanoff, J., Webb, N. E., & Jamieson, A. S. (2016). Expect the unexpected: A paradoxical effect of cue validity on the orienting of attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78, 2124–2134.

Klein, R. M., & Hilchey, M. D. (2011). Oculomotor inhibition of return. In S. Liversedge, I. D. Gilchrist, & S. Everling (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of eye movements (pp. 471– 492). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kleiner, M., Brainard, D., Pelli, D. (2007). “What’s new in Psychtoolbox-3?” Perception 36 ECVP Abstract Supplement.

Lahav, A., Makovski, T., & Tsal, Y. (2012). White bear everywhere: Exploring the boundaries of the attentional white bear phenomenon. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74, 661–673.

Lamy, D., Tsal, Y., & Egeth, H. E. (2003). Does a salient distractor capture attention early in processing? Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 10, 621–629.

Leber, A. B., & Egeth, H. E. (2006). It’s under control: Top-down search strategies can override attentional capture. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 13, 132–138.

Maljkovic, V., & Nakayama, K. (1996). Priming of pop-out: II. The role of position. Perception & Psychophysics, 58, 977–991.

Moher, J., & Egeth, H. E. (2012). The ignoring paradox: Cueing distractor features leads first to selection, then to inhibition of to-be-ignored items. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 74, 1590–1605.

Munneke, J., Van der Stigchel, S., & Theeuwes, J. (2008). Cueing the location of a distractor: An inhibitory mechanism of spatial attention? Acta Psychologica, 129, 101–107.

Pfister, R., & Janczyk, M. (2013). Confidence intervals for two sample means: Calculation, interpretation, and a few simple rules. Advances in Cognitive Psychology, 9, 74–80.

Rabbitt, P., Cumming, G., & Vyas, S. (1979). Modulation of selective attention by sequential effects in visual search tasks. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 31, 305–317.

Rajsic, J., Wilson, D. E., & Pratt, J. (2015). Confirmation bias in visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 41, 1353–1364.

Sawaki, R., & Luck, S. J. (2010). Capture versus suppression of attention by salient singletons: Electrophysiological evidence for an automatic attend-to-me signal. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 72, 1455–1470.

Serences, J. T., Yantis, S., Culberson, A., & Awh, E. (2004). Preparatory activity in visual cortex indexes distractor suppression during covert spatial orienting. Journal of Neurophysiology, 92, 3538–3545.

Shore, D. I., Spence, C., & Klein, R. M. (2001). Visual prior entry. Psychological Science, 12, 360–366.

Theeuwes, J. (1992). Perceptual selectivity for color and form. Perception & Psychophysics, 51, 599–606.

Theeuwes, J., & Burger, R. (1998). Attentional control during visual search: The effect of irrelevant singletons. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 24, 1342.

Theeuwes, J., de Vries, G., & Godijn, R. (2003). Attentional and oculomotor capture with static singletons. Perception & Psychophysics, 65, 735–746.

Tsal, Y., & Makovski, T. (2006). The attentional white bear phenomenon: The mandatory allocation of attention to expected distractor locations. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 32, 351–363.

Van der Stigchel, S., & Theeuwes, J. (2006). Our eyes deviate away from a location where a distractor is expected to appear. Experimental Brain Research, 169, 338–349.

Wegner, D. M. (2009). How to think, say, or do precisely the worst thing for any occasion. Science, 325, 48–50.

Wegner, D. M., Ansfield, M., & Pilloff, D. (1998). The putt and the pendulum: Ironic effects of the mental control of action. Psychological Science, 9, 196–199.

Wegner, D. M., & Erber, R. (1992). The hyperaccessibility of suppressed thoughts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63, 903–912.

Yantis, S., & Jonides, J. (1990). Abrupt visual onsets and selective attention: Voluntary versus automatic allocation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 16, 121.

Zelinsky, G. J. (2008). A Theory of Eye Movements during Target Acquisition. Psychological Review, 115, 787–835.

Zhao, J., Al-Aidroos, N., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2013). Attention is spontaneously biased toward regularities. Psychological Science, 24, 667–677.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This project was supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, in form of a discovery grant to Jay Pratt and a Postgraduate Scholarship-Doctoral to Jason Rajsic.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huffman, G., Rajsic, J. & Pratt, J. Ironic capture: top-down expectations exacerbate distraction in visual search. Psychological Research 83, 1070–1082 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-017-0917-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-017-0917-z