Abstract

Objective

We estimated the use of prescribed analgesics and adjuvants among nursing home residents without cancer who reported pain at their admission assessment, in relation to resident-reported pain severity.

Methods

Medicare Part D claims were used to define 3 classes of analgesics and 7 classes of potential adjuvants on the 21st day after nursing home admission (or the day of discharge for residents discharged before that date) among 180,780 residents with complete information admitted between January 1, 2011 and December 9, 2016, with no cancer diagnosis.

Results

Of these residents, 27.9% reported mild pain, 46.6% moderate pain, and 25.6% reported severe pain. The prevalence of residents in pain without Part D claims for prescribed analgesic and/or adjuvant medications was 47.3% among those reporting mild pain, 35.7% among those with moderate pain, and 24.8% among those in severe pain. Among residents reporting severe pain, 33% of those ≥ 85 years of age and 35% of those moderately cognitively impaired received no prescription analgesics/adjuvants. Use of all classes of prescribed analgesics and adjuvants increased with resident-reported pain severity, and the concomitant use of medications from multiple classes was common.

Conclusion

Among nursing home residents with recognized pain, opportunities to improve the pharmacologic management of pain, especially among older residents, and those living with cognitive impairments exist.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In the USA, there are ~ 1.7 million certified nursing home beds [1]. For the residents who live in this healthcare setting, pain is a common occurrence [2, 3]. If not treated appropriately, pain may be associated with complications such as depression, decreased social engagement, increased healthcare utilization and costs, increased functional limitations, and poor treatment outcomes [4,5,6]. The effective management of pain is key to improving or maintaining the quality of life of older adults.

In older adults, pharmacological treatment of pain can be challenging due to age-related physiologic changes, polypharmacy, and multimorbidity that may increase the risk of adverse events [7]. Cognitive and sensory impairments in old age also contribute to the inability of patients to effectively communicate about their pain with health professionals, which can negatively influence the types and intensity of treatments that are provided [8, 9]. Furthermore, uncertainty remains about the long-term safety and efficacy of common analgesics, and a lack of knowledge about both the cause of common pain syndromes [10] and the effectiveness of interventions to improve pain management [11].

Previously, we have shown that non-malignant pain recognition and management in nursing homes is sub-optimal, with up to one quarter of residents with daily pain not receiving any analgesics for treatment [12,13,14], despite clinical practice guidelines [15]. Using a national database of nursing home residents (2011–2016), this study aimed to provide a contemporary description of prescription analgesic and adjuvant use by pain severity among nursing home residents, to estimate the prevalence of lack of prescription analgesic use across levels of pain severity, and to identify factors associated with lack of prescription analgesics and/or adjuvants for residents with reported pain.

Methods

This study was approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Review Board.

Sample selection

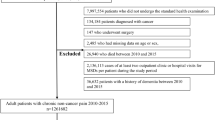

We used the Minimum Data Set 3.0 [16, 17]. which is a valid and reliable tool completed by nursing home staff on virtually every nursing home resident in the USA. Used for research purposes [18], it includes a comprehensive admission assessment information of sociodemographics, active clinical diagnoses, and measures of functional [19] and cognitive status [20]. Supplemental Table 1 provides a detailed description of the sample selection.

Pain medications

Although the effectiveness of non-pharmacological approaches to pain management is recognized [21], pharmacological approaches are the most commonly used to treat pain in older adults [4]. We focused on the use of analgesics or adjuvant medications for pain. We developed an expansive list of potential analgesics and adjuvants guided by trusted resources [15, 22] and reviewed by an expert in geriatric pharmacotherapy (AH). We categorized prescription analgesics as short-acting opioids (e.g., hydrocodone), long-acting opioids (e.g., fentanyl patches), and non-opioid analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen not in cold preparations or other combinations, celecoxib). We categorized prescription adjuvants into 7 categories: gabapentinoids, other anticonvulsant adjuvants (e.g., carbamazepine), SNRI antidepressants (e.g., duloxetine), tricyclic antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline), muscle relaxants (e.g., clonazepam), systemic glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone), and lidocaine patches. Residents with prescriptions with a day’s supply covering the index date were considered users of that medication. We then determined which classes of medications were used alone, or in combination with other classes of prescribed analgesics and/or adjuvants on the index date.

Pain severity

The MDS 3.0 was changed significantly in October 2010 [23], with more opportunities for the “resident’s voice” to be heard [24]. Residents had documented pain in the lookback window of 5 days, and a self-assessment of pain severity, by one of two methods: a numeric pain intensity rating (J06a: “Please rate your worst pain over the last 5 days on a zero to ten scale, with zero being no pain and ten as the worst pain you can imagine.”), or a verbal descriptor scale (J06b: “Please rate the intensity of your worst pain over the last 5 days: mild; moderate; severe; very severe, horrible.”). Pain intensity ratings from 0 to 4 were tabulated with “mild” pain, pain intensity ratings from 5 to 7 were tabulated with “moderate” pain, and pain intensity ratings from 8 to 10 were tabulated with “severe” pain, as were residents who reported “very severe, horrible” pain. The MDS 3.0 provides the frequency of pain (i.e., rarely, occasionally, frequently, almost constantly), whether or not pain affects sleep, and whether or not pain limits day-to-day activities.

Covariates

We selected demographics (age group, sex, race/ethnicity, admission source, and dependence in activities of daily living (ADL) [19]); potentially painful conditions from Section I (e.g., surgical wounds, arthritis, diabetes); conditions that may influence the communication of pain (e.g., cognitive function score [20], Alzheimer’s or other dementias); and conditions that may modify the pain experience (e.g., depression). Residents were classified as independent (ADL score 0–2), modified dependence (score 3–4), or dependent (score 5–6).

Analytic strategy

With large sample sizes, trivial differences are often highly statistically significant. Instead, we considered absolute differences greater than 5% to be noteworthy. We described the distributions of key covariates and the use of monotherapy and combinations of analgesics or adjuvants by level of pain severity. The prevalence of a lack of prescribed analgesic/adjuvant medications was estimated, stratified by pain severity. We used a linear modeling approach (logarithmic link function with a Poisson distribution [25]) to estimate adjusted prevalence ratios with 95% confidence limits, overall and stratified by resident-reported pain severity.

Results

Of 180,780 nursing home residents with documented pain (Fig. 1), 27.9% reported mild pain, 46.6% moderate pain, and 25.6% severe pain. Among the 27.9% reporting mild pain, 47.3% had no Part D claims for analgesics or adjuvants; 22.7% reported their pain frequency as rarely, 63.4% as occasionally, 10.7% as frequently, and 2.5% as almost constantly. Among the 46.6% reporting moderate pain, 35.7% had no Part D claims for analgesic or adjuvants; 7.2% reported their pain frequency as rarely, 55.9% as occasionally, 30.1% as frequently, and 6.2% as almost constantly. Among the 25.6% reporting severe pain, 3.5% reported their pain frequency as rarely, 28.7% as occasionally, 44.0% as frequently, and 22.9% as almost constantly, with 42.4% reporting that pain affects sleep and 52.8% indicating that pain limits day-to-day activities. Among those reporting severe pain, 24.8% had no Part D claims for analgesic or adjuvants.

While distributions of sex, race/ethnicity, activities of daily living, and potentially painful conditions were similar across level of pain severity, the distribution of age varied across levels of pain severity with 44.6% of those in mild pain ≥ 85 years of age whereas 34.0% of those in severe pain were ≥ 85 years of age (Table 1). The distribution of cognitive impairment and active diagnoses of Alzheimer’s or other dementias were different across levels of pain severity.

Short-acting opioids were commonly used (Table 2: 23.3% among those with mild pain, 34.9% of those with moderate pain, and 46.5% of those with severe pain). Regardless of the level of pain severity, more than half receiving short-acting opioids used them in combination with long-acting opioids, non-opioid analgesics, and/or potential adjuvants. For example, among short-acting opioid users in severe pain, 54% also used potential adjuvants (25.2% of the whole sample), 20% also used long-acting opioids (9.3% of the whole sample), and 14% used non-opioid analgesics (6.6% of the whole sample). Non-opioid analgesics were used in 10.6% of those with mild pain, 12.0% of those in moderate pain, and 13.2% of those in severe pain. Potential adjuvant medications were used by 34.0% of those with mild pain and 48.0% of those with severe pain, with gabapentinoids most common. Use of other anticonvulsants was < 5%, regardless of level of pain severity. SNRI antidepressants were used in 7.8% of residents with mild pain, 9.6% of residents with moderate pain, and 12.3% of residents with severe pain. Muscle relaxants were used in 5.4% of residents with mild pain, 6.4% in those with moderate pain, and 7.8% of those reporting severe pain. No pain management strategies were documented for 19.8% of those in mild pain, 12.0% of those in moderate pain, and 11.4% of those in severe pain (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 3 shows that increasing pain severity was inversely associated with lack of receipt of pharmacological pain medications (adjusted PR moderate versus mild, 0.80 (95% CI 0.79–0.82), adjusted PR severe versus mild, 0.60 (95% CI 0.59–0.62)). Factors placing residents at greater risk of not receiving prescription medications included advanced age (adjusted PR age ≥ 85 years versus 50–64 years, 2.00 (95% CI 1.93–2.08)), moderate to severe cognitive impairment (adjusted PR, 1.20 (95% CI 1.17–1.22)), and having Alzheimer’s disease or other dementias (adjusted PR, 1.14 (95% CI 1.12–1.17)). Estimates of prevalence ratios were similar across the three levels of pain severity (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

This study attempted to shed more light on the prescription pain management strategies used in nursing home residents with documented pain. This study did not include residents without pain documented because they either did not experience pain in the 5 days preceding the MDS assessment or the pain management strategies used adequately controlled their pain. We previously have noted that advanced age, race/ethnicity, cognitive impairment, and dementia were inversely associated with persistent and intermittent pain [3, 12, 13], findings aligned with research by others [26, 27]. We demonstrated that among those who self-reported pain, those reporting severe pain were less likely to be of advanced age or to have cognitive impairment relative to those reporting mild pain. Exploring whether stoicism in advanced age explains our findings, as has been reported by others [28], is beyond the scope of our data. Concerns about MDS 3.0 pain measures have been noted [29, 30]. The MDS 3.0 offered significant improvements to capturing the resident experience [23] and the vast majority of residents provide self-reported information [24]. Continued efforts to improve the recognition of pain in nursing home residents is warranted.

Among nursing home residents with recognized pain, one in four rated their pain as severe, with two-thirds of residents with severe pain noting it occurred frequently or almost constantly. Pain impacted residents’ sleep and limited residents’ ability to do day-to-day activities, and this increased with level of pain severity. Prescribed analgesics and adjuvants increased markedly with pain severity for all groups of analgesics and adjuvants considered. However, 24.8% lacked prescription medications for pain among those with identified severe pain. Residents aged ≥ 85 years were least likely to receive prescribed analgesics or adjuvants as compared with younger nursing home residents. Cognitively impaired residents were more likely to endure their pain without the use of prescribed analgesics or adjuvants relative to residents with mild cognitive impairment.

We found that in those with pain recognized and documented by nursing home staff, lack of prescription analgesics was common, although less frequent with increased severity of pain. In the USA, nursing homes are required by law (42 CFR §483.60) to provide pharmaceutical services to meet the needs of each resident [31]. Our findings documenting the extent to which residents with documented pain had no Part D claims for prescription analgesics, indicate that opportunities to enhance compliance with this federal legislation are plentiful. Advanced age and level of cognitive impairment were associated with decreased use of prescription pain medications, consistent with what others have shown [32, 33]. The US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services provided revised guidance for meeting compliance in the evaluation and management of pain in nursing home residents (i.e., F-Tag 309) in 2009. Such administrative initiatives appear to fall short. The extent to which these findings have been influenced by federal efforts to address opioid abuse is unknown [34]. Despite these efforts, improving pain management in nursing home residents deserving of relief from suffering and dignity in care [35] is imperative.

Consistent with previous research, we found that opioid use was common [36], as was use of gabapentinoids [37, 38]. With increased severity of pain, we see increased use of combination therapies, suggesting that nursing homes often aggressively attempt to manage pain. Our data do not permit us to evaluate the extent to which the “right” pain medications or combination of analgesics and/or adjuvants are given to the “right” residents at the “right” time [39]. The Institute of Medicine’s report “Relieving Pain in America” challenged researchers to implement a cultural transformation to better understand pain and its management [40]. Foundational knowledge about how best to support nursing homes to continue improving pain management among those in life’s final chapter is needed.

Our data should be interpreted with caution as we were unable to include those receiving Medicare managed care or post-acute rehabilitation. Extrapolation of the findings from this study to residents covered by managed care, or to residents receiving post-acute rehabilitation services, should be undertaken with caution. Residents without Part D claims for analgesics or adjuvants may have received non-prescription pain relief and/or non-pharmacologic pain management. The MDS 3.0 lacks specific details about what non-pharmacological approaches or over the counter medications were used for pain. The use of prescribed adjuvant medications (e.g., SNRI antidepressants, systemic glucocorticoids, anticonvulsants) may have been for indications other than pain.

Conclusions

Many nursing home residents with pain receive no prescription pharmacological management 3 weeks into their stay. Those with cognitive impairment and those with advanced age (≥ 85 years) had the greatest likelihood of no treatment. In those whose pain is treated, use of combination analgesics +/- adjuvants increased with severity of pain. Understanding whether lack of prescription pharmacological management of pain among those with moderate to severe pain at admission reflects resident preference, clinician uncertainty given the lack of a strong evidence base regarding risks and benefits in nursing home residents, or other modifiable factors is warranted to provide “personalized” pain management to a population deserving of improved quality of life [41].

References

Harrington C, Carrillo H, Garfield R. Nursing facilities, staffing, residents and facilities deficiencies, 2004 through 2009 [online]. Available from: http://files.kff.org/attachment/REPORT-Nursing-Facilities-Staffing-Residents-and-Facility-Deficiencies-2009-2015, Accessed on 2 Nov 2019

Fries BE, Simon SE, Morris JN, Flodstrom C, Bookstein FL (2001) Pain in U.S. Nursing homes: validating a pain scale for the Minimum Data Set. The Gerontologist 41(2):173–179

Hunnicutt JN, Ulbricht CM, Tjia J, Lapane KL (2017) Pain and pharmacologic pain management in long-stay nursing home residents. Pain. 158(6):1091–1099

Panel AGS (2002) on Persistent Pain in Older Persons. The management of persistent pain in older persons. American Geriatrics Society. J Am Geriatr Soc 50:S205–S224

Kolanowski A, Mogle J, Fick DM et al (2015) Pain, delirium, and physical function in skilled nursing home patients with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16(1):37–40

Cordner Z, Blass DM, Rabins PV, Black BS (2010) Quality of life in nursing home residents with advanced dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc 58(12):2394–2400

Lamy PP (1991) Physiological changes due to age. Drugs Aging 5:385–404

McLachlan AJ, Bath S, Naganathan V et al (2011) Clinical pharmacology of analgesic medicines in older people: impact of frailty and cognitive impairment. Br J Clin Pharmacol 71(3):351–364

Lautenbacher S, Peters JH, Heesen M, Scheel J, Kunz M (2017) Age changes in pain perception: a systematic-review and meta-analysis of age effects on pain and tolerance thresholds. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 75:104–113

Reid MC, Bennett DA, Chen WG et al (2011) Improving the pharmacologic management of pain in older adults: identifying the research gaps and methods to address them. Pain Med 12(9):1336–1357

Herman AD, Johnson TM, Ritchie CS, Parmelee PA (2009) Pain management interventions in the nursing home: a structured review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:1258–1267

Won A, Lapane KL, Gambassi G et al (1999) Correlates and management of nonmalignant pain in the nursing home. J Am Geriatr Soc 47(8):936–942

Won AB, Lapane KL, Vallow S et al (2004) Persistent nonmalignant pain and analgesic prescribing patterns in elderly nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(6):867–874

Lapane KL, Quilliam BJ, Chow W, Kim MS (2013) Pharmacologic management of non-cancer pain among nursing home residents. J Pain Symptom Manag 45(1):33–42

American Geriatrics Society Panel on the Pharmacological Management of Persistent Pain in Older Persons (2009) Pharmacological management of persistent pain in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 57:1331–1346

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed 23 Oct 2019]; Long Term Care Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0. 2011 Available from: https://www.resdac.org/cms-data/request/cms-data-request-center

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Accessed 23 Oct 2019]; Long-term care facility resident assessment instrument 3.0 User’s Manual, Version 1.14. 2016 Oct; Available from: https://downloads.cms.gov/files/MDS-30-RAI-Manual-V114-October-2016.pdf

Saliba D, Buchanan J (2012) Making the investment count: revision of the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes, MDS 3. 0. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13(7):602–610

Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA (1999) Scaling ADLs within the MDS. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 54:M546–M553

Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V (2017) The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care 55:e68–e72

Eccleston C, Williams AC, Morley S (2009) Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD007407

(2018) Goodman and Gilman’s The pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 13th edition. New York, McGraw and Hill

Saliba D, Jones M, Streim J et al (2012) Overview of significant changes in the Minimum Data Set for nursing homes version 3. 0. J Am Med Dir Assoc 13:595–601

Thomas KS, Wysocki A, Intrator O, Mor V (2014) Finding Gertrude: the resident’s voice in MDS 3. 0. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15(11):802–806

Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E (2005) Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol 3(1):199–200

Fain KM, Alexander GC, Dore DD et al (2017) Frequency and predictors of analgesic prescribing in U.S. nursing home residents with persistent pain. J Am Geriatr Soc 65(2):286–293

Shen X, Zucerkman IH, Palmer JB, Stuart B (2015) Trends in prevalence for moderate-to-severe pain and persistent pain among Medicare beneficiaries in nursing homes, 2006–2009. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 70:598–603

Yong HH (2006) Can attitudes of stoicism and cautiousness explain observed age-related variation in levels of self-rated pain, mood disturbance and functional interference in chronic pain patients? Eur J Pain 10(5):399–407

Wei YJ, Solberg L, Chen C et al (2019) Pain assessments in MDS 3.0: agreement with vital sign pain records of nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 12. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16122

Dubé CE, Mack DS, Hunnicutt JN, Lapane KL (2018) Cognitive impairment and pain among nursing home residents with cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag 55(6):1509–1518

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CFR-2011-title42-vol5/pdf/CFR-2011-title42-vol5-sec483-60.pdf, Accessed 9 Nov 2019.

Bauer U, Pitzer S, Schreier MM et al (2016) Pain treatment for nursing home residents differs according to cognitive state–a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr 16:124

Husebo BS, Strand LI, Moe-Nilssen R, Borgehusebo S, Aarsland D, Ljunggren AE (2008) Who suffers most? Dementia and pain in nursing home patients: a cross-sectional study. J Am Med Dir Assoc 9(6):427–433

U.S. Department of Health and Human Servicees. HHS takes strong steps to address opioid-drug related overdose, death and dependence. March 26, 2015. [Accessed March 02, 2020] Available at: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/03/26/hhs-takes-strong-steps-to-address-opioid-drug-relatedoverdose-death-and-dependence.html

Kumar A, Allock N (2008) Pain in older people: reflections and experiences from an older person’s perspective. British Pain Society, Help the Aged, London

Hunnicutt JN, Chrysanthopoulou SA, Ulbricht CM et al (2018) Prevalence of long-term opioid use in long-stay nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 66(1):48–55

Callegari C, Ielmini M, Bianchi L et al (2016) Antiepileptic drug use in a nursing home setting: a retrospective study in older adults. Funct Neurol 31(2):87–93

Zhao D, Sridharmurthy D, Yuan Y et al (2019) The prevalence, prescribing patterns and factors associated with antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents. Drugs Aging:xx–xx

Corbett A, Husebo B, Malcangio M et al (2012) Assessment and treatment of pain in people with dementia. Nat Rev Neurol 8(5):264–274

Institute of Medicine (IOM) (2011) Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Tse MMY, Wan VTC, Vong SKS (2013) Health-related profile and quality of life among nursing home residents: does pain matter? Pain Manag Nurs 14(4):e717–e184

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute of Nursing Research (grant number: NR016977).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. Lapane secured funding, acquired the data, conceived of the study idea, and wrote parts of the initial manuscript draft. Drs. Lapane, Hume, and Jesdale developed the original design. Dr. Morrison assisted in interpreting the data, writing the first draft, and critically evaluating the work. Dr. Jesdale took the lead on conducting the analysis. Dr. Hume took the lead on operationalizing the medications and provided oversight on how we categorized the medication information. All authors critically evaluated the manuscript and contributed to the final product.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Keypoints

• Nursing home residents commonly experience pain.

• Medication management of pain could be improved as one in four residents in severe pain received no pain medications or adjuvants to pain medications.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lapane, K.L., Hume, A.L., Morrison, R.A. et al. Prescription analgesia and adjuvant use by pain severity at admission among nursing home residents with non-malignant pain. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 76, 1021–1028 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02878-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02878-0