Abstract

Summary

RANKL was administered continuously to rats for 28 days to investigate its potential as a disease model for the skeletal system. Bone turnover rates, bone material, structural and mechanical properties were evaluated. RANKL infusion caused overall skeletal complications comparable to those in high bone-turnover conditions, such as postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Introduction

RANKL is an essential mediator for osteoclast development. No study has examined in detail the direct skeletal consequences of excess RANKL on bone turnover, mineralization, architecture, and vascular calcification. We, therefore, administrated soluble RANKL continuously into mature rats and created a bone-loss model.

Methods

Six-month-old Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were assigned to three groups (n = 12) receiving continuous administration of saline (VEH) or human RANKL (35 μg/kg/day, LOW or 175 μg/kg/day, HI) for 28 days. Blood was collected routinely during the study. At sacrifice, hind limbs and aorta were removed and samples were analyzed.

Results

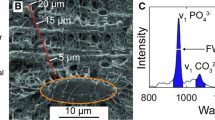

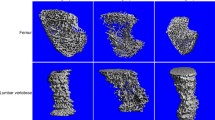

High dose RANKL markedly stimulated serum osteocalcin and TRAP-5b levels and reduced femur cortical bone volume (−7.6%) and trabecular volume fraction (BV/TV) at the proximal tibia (−64% vs. VEH). Bone quality was significantly degraded in HI, as evidenced by decreased femoral percent mineralization, trabecular connectivity, and increased endocortical bone resorption perimeters. Both cortical and trabecular bone mechanical properties were reduced by high dose RANKL. No differences were observed in the mineral content of the abdominal aorta.

Conclusions

Continuous RANKL infusion caused general detrimental effects on rat skeleton. These changes are comparable to those commonly observed in high-turnover bone diseases such as postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hofbauer LC, Schoppet M (2004) Clinical implications of the osteoprotegerin/RANKL/RANK system for bone and vascular diseases. Jama 292:490–495

Coleman RE (1997) Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer 80:1588–1594

Blair JM, Zhou H, Seibel MJ et al (2006) Mechanisms of disease: roles of OPG, RANKL and RANK in the pathophysiology of skeletal metastasis. Nat Clin Pract Oncol 3:41–49

Teitelbaum SL (2000) Bone resorption by osteoclasts. Science 289:1504–1508

Boyle WJ, Simonet WS, Lacey DL (2003) Osteoclast differentiation and activation. Nature 423:337–342

Suda T, Takahashi N, Udagawa N et al (1999) Modulation of osteoclast differentiation and function by the new members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor and ligand families. Endocr Rev 20:345–357

Zaidi M, Blair HC, Moonga BS et al (2003) Osteoclastogenesis, bone resorption, and osteoclast-based therapeutics. J Bone Miner Res 18:599–609

Fuller K, Wong B, Fox S et al (1998) TRANCE is necessary and sufficient for osteoblast-mediated activation of bone resorption in osteoclasts. J Exp Med 188:997–1001

Eghbali-Fatourechi G, Khosla S, Sanyal A et al (2003) Role of RANK ligand in mediating increased bone resorption in early postmenopausal women. J Clin Invest 111:1221–1230

Anderson DM, Maraskovsky E, Billingsley WL et al (1997) A homologue of the TNF receptor and its ligand enhance T-cell growth and dendritic-cell function. Nature 390:175–179

Lacey DL, Timms E, Tan HL et al (1998) Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93:165–176

Yasuda H, Shima N, Nakagawa N et al (1998) Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:3597–3602

Simonet WS, Lacey DL, Dunstan CR et al (1997) Osteoprotegerin: a novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell 89:309–319

Tsuda E, Goto M, Mochizuki S et al (1997) Isolation of a novel cytokine from human fibroblasts that specifically inhibits osteoclastogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 234:137–142

Nagai M, Sato N (1999) Reciprocal gene expression of osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor and osteoclast differentiation factor regulates osteoclast formation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257:719–723

Fazzalari NL, Kuliwaba JS, Atkins GJ et al (2001) The ratio of messenger RNA levels of receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand to osteoprotegerin correlates with bone remodeling indices in normal human cancellous bone but not in osteoarthritis. J Bone Miner Res 16:1015–1027

Grimaud E, Soubigou L, Couillaud S et al (2003) Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL)/osteoprotegerin (OPG) ratio is increased in severe osteolysis. Am J Pathol 163:2021–2031

Haynes DR, Crotti TN, Loric M et al (2001) Osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) regulate osteoclast formation by cells in the human rheumatoid arthritic joint. Rheumatology (Oxford) 40:623–630

Kong YY, Feige U, Sarosi I et al (1999) Activated T cells regulate bone loss and joint destruction in adjuvant arthritis through osteoprotegerin ligand. Nature 402:304–309

Stolina M, Adamu S, Ominsky M et al (2005) RANKL is a marker and mediator of local and systemic bone loss in two rat models of inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Miner Res 20:1756–1765

Giuliani N, Bataille R, Mancini C et al (2001) Myeloma cells induce imbalance in the osteoprotegerin/osteoprotegerin ligand system in the human bone marrow environment. Blood 98:3527–3533

Standal T, Seidel C, Hjertner O et al (2002) Osteoprotegerin is bound, internalized, and degraded by multiple myeloma cells. Blood 100:3002–3007

Michigami T, Ihara-Watanabe M, Yamazaki M et al (2001) Receptor activator of nuclear factor kappaB ligand (RANKL) is a key molecule of osteoclast formation for bone metastasis in a newly developed model of human neuroblastoma. Cancer Res 61:1637–1644

Mundy GR (2002) Metastasis to bone: causes, consequences and therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer 2:584–593

Fuller K, Gallagher AC, Chambers TJ (1991) Osteoclast resorption-stimulating activity is associated with the osteoblast cell surface and/or the extracellular matrix. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 181:67–73

Ikeda T, Kasai M, Utsuyama M et al (2001) Determination of three isoforms of the receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappaB ligand and their differential expression in bone and thymus. Endocrinology 142:1419–1426

Suzuki J, Ikeda T, Kuroyama H et al (2004) Regulation of osteoclastogenesis by three human RANKL isoforms expressed in NIH3T3 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 314:1021–1027

Avbersek-Luznik I, Balon BP, Rus I et al (2005) Increased bone resorption in HD patients: is it caused by elevated RANKL synthesis? Nephrol Dial Transplant 20:566–570

Geusens PP, Landewe RB, Garnero P et al (2006) The ratio of circulating osteoprotegerin to RANKL in early rheumatoid arthritis predicts later joint destruction. Arthritis Rheum 54:1772–1777

Morabito N, Gaudio A, Lasco A et al (2004) Osteoprotegerin and RANKL in the pathogenesis of thalassemia-induced osteoporosis: new pieces of the puzzle. J Bone Miner Res 19:722–727

Abrahamsen B, Hjelmborg JV, Kostenuik P et al (2005) Circulating amounts of osteoprotegerin and RANK ligand: genetic influence and relationship with BMD assessed in female twins. Bone 36:727–735

Min H, Morony S, Sarosi I et al (2000) Osteoprotegerin reverses osteoporosis by inhibiting endosteal osteoclasts and prevents vascular calcification by blocking a process resembling osteoclastogenesis. J Exp Med 192:463–474

Broz JJ, Simske SJ, Greenberg AR et al (1993) Effects of rehydration state on the flexural properties of whole mouse long bones. J Biomech Eng 115:447–449

Ross AB, Bateman TA, Kostenuik PJ et al (2001) The effects of osteoprotegerin on the mechanical properties of rat bone. J Mater Sci Mater Med 12:583–588

Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH et al (1987) Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2:595–610

Stilgren LS, Hegedus LM, Beck-Nielsen H et al (2003) Osteoprotegerin levels in primary hyperparathyroidism: effect of parathyroidectomy and association with bone metabolism. Calcif Tissue Int 73:210–216

Stilgren LS, Rettmer E, Eriksen EF et al (2004) Skeletal changes in osteoprotegerin and receptor activator of nuclear factor-kappab ligand mRNA levels in primary hyperparathyroidism: effect of parathyroidectomy and association with bone metabolism. Bone 35:256–265

Heaney RP (2003) Is the paradigm shifting? Bone 33:457–465

Turner CH (2002) Biomechanics of bone: determinants of skeletal fragility and bone quality. Osteoporos Int 13:97–104

Bucay N, Sarosi I, Dunstan CR et al (1998) osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev 12:1260–1268

Abdallah BM, Stilgren LS, Nissen N et al (2005) Increased RANKL/OPG mRNA ratio in iliac bone biopsies from women with hip fractures. Calcif Tissue Int 76:90–97

Beck TJ, Miller PD, Lewiecki EM (2006) Denosumab improves the structural geometry of the proximal femur in postmenopausal women with low bone mass. J Bone Min Res 21:S71 (Abstract)

McClung MR, Lewiecki EM, Cohen SB et al (2006) Denosumab in postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density. N Engl J Med 354:821–831

Body JJ, Facon T, Coleman RE et al (2006) A study of the biological receptor activator of nuclear factor-{kappa}B ligand inhibitor, denosumab, in patients with multiple myeloma or bone metastases from breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 12:1221–1228

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Space Biomedical Research Institute through NASA NCC 9–58, Amgen, Inc., and BioServe Space Technologies (through NASA NCC8–242). The authors are grateful to Nessa Hawkins and Brian Williamson (Amgen) for producing and purifying recombinant RANKL. The editorial and formatting assistance of Jenny Bourne is greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of interest

Drs. Kostenuik, Ominsky, Asuncion, Morony and Adamu are employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc.; Dr. Bateman receives grant support from Amgen.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yuan, Y.Y., Kostenuik, P.J., Ominsky, M.S. et al. Skeletal deterioration induced by RANKL infusion: a model for high-turnover bone disease. Osteoporos Int 19, 625–635 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0509-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-007-0509-7