Abstract

There exists extensive literature analyzing the effect of sibship size and a child’s educational attainment, termed the quantity-quality (QQ) trade-off. Studies using data from developed countries tend to find limited or nonexistent effects, while studies that use data from developing countries find a wide range of relationships. We study a possible explanation for these seemingly contradictory findings that the existence or non-existence of a QQ trade-off is correlated with the socioeconomic context within which the family resides. We use the census files comprised of the entire Taiwan population in the years 1980, 1990, and 2000, reflecting different levels of economic growth across time, coupled with an instrumental variable approach and more than 7000 village fixed effects. Our results indicate that sibship size has large and significant effects on educational outcomes, measured in terms of high school and college enrollments, for early birth cohorts, and the effects diminish for more recent birth cohorts. In addition, we find that areas in different developmental stages face different QQ trade-offs: areas with higher levels of development only have trade-offs among higher measures of quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The year of school completed is used as an education outcome for the cohort born between 1968 and 1977, and dummy variables indicating whether one completes junior and senior high schools are used for the cohort born from 1978 to 1981.

Due to industrialization and high technology development, the growth rates of these four areas exceeded seven percent a year between the early 1960s and 1990s.

Progression rate for tier j is calculated as the number of graduates of tier j + 1 divided by the number of graduates of tier j.

We do not focus on children between the ages of 7 and 15 (Oreopoulos et al. 2006) because grade repetition is not common in compulsory education in Taiwan.

General colleges include both universities and 5-year vocational colleges.

The compulsory education was extended from six years to nine years in 1968 in Taiwan, and those who were born in or after 1956 (aged 12 or under in 1968) are affected by the reform. Therefore, all of our studied cohorts are affected by this educational reform.

We exclude twins at first birth to avoid the inherent difference between twins and singletons, and exclude twins at second birth to avoid the increase in number of children due to a twin birth. Twins at the first two births consist of 1.1%, 1.9%, and 1.7% of our study sample in waves 1980, 1990, and 2000, respectively.

In Taiwan census, college students are still considered as living with their parents.

According to National Statistics, Republic of China (Taiwan), the average ages at first marriage of married women (age ≥ 15) were 21.23, 21.88, and 22.71 in 1980, 1990 and 2000, respectively. The average ages at first birth of married women (age ≥ 15) were 22.47, 23.19, and 23.97 in 1980, 1990, and 2000, respectively (source: https://eng.stat.gov.tw/ct.asp?xItem=37195&CtNode=1662&mp=5).

These percentages represent the high school enrollment rates for 16–17-year-olds and the college enrollment rates for 18–19-year-olds.

The proportions for son preference are 45%, 27%, and 12% in 1979, 1992, and 2002, respectively. Those statistics are based on the Knowledge, Attitudes and the Practice of Contraceptives surveys, 1973–1998 and 2002 National Survey on Knowledge, Attitudes and Practice of Health Promotion. We chose the survey years that are closest to the census years.

The proportions of women who are indifferent about the gender composition of their children are 8% in 1979, 22% in 1992, and 35% in 2002.

The median number of households in each township/district is 1458, 3310, and 3449 in 1980, 1990, and 2000, respectively.

References

Angrist JD, Evans WN. Children and their parents’ labor supply: evidence from exogenous variation in family size. Am Econ Rev. 1998;88(3):450–77.

Angrist JD, Lavy V, Schlosser A. Multiple experiments for the causal link between the quantity and quality of children. J Labor Econ. 2010;28(4):773–824.

Becker GS. An economic analysis of fertility. In: Coale A, editor. Demographic and economic change in developed countries. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1960.

Becker GS, Lewis HG. On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ. 1973;81(2, Part 2):S279–88.

Becker GS, Tomes N. Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. J Polit Econ. 1976;84(4):S143–62.

Black SE, Devereux PJ, Salvanes KG. The more the merrier? The effect of family size and birth order on children’s education. Q J Econ. 2005;120(2):669–700.

Blake J. Family size and the quality of children. Demography. 1981;18(4):421–42.

Brinch CN, Mogstad M, Wiswall M. Beyond LATE with a discrete instrument. J Polit Econ. 2017;125(4):985–1039.

Chuang YC, Chao CY. educational choice, wage determination, and rates of return to education in Taiwan. Int Adv Econ Res. 2001;7(4):479–504.

Cáceres-Delpiano J. The impacts of family size on investment in child quality. J Human Resour. 2006;41(4):738–54.

Chen C, Chou SY, Wang C, Zhao W. The effect of the second child on the anthropometric outcomes and nutrition intake of the first child: evidence from the relaxation of the one-child policy in rural China. BE J Econ Anal Policy. 2020;20(1):50.

Dahl GB, Moretti E. The demand for sons. Rev Econ Stud. 2008;75(4):1085–120.

Featherman D, Hauser R. Opportunity and change. New York: Academic Press; 1978.

Gindling TH, Goldfarb M, Chang C-C. Changing returns to education in Taiwan: 1978–1991. World Dev. 1995;23(2):343–56.

Hank K. Parental gender preferences and reproductive behaviour: a review of the recent literature. J Biosoc Sci. 2007;39(5):759–67.

Hanushek EA. The trade-off between child quantity and quality. J Polit Econ. 1992;100(1):84–117.

Liu JT, Chou SY, Liu JL. Asymmetries in progression in higher education in Taiwan: parental education and income effects. Econ Educ Rev. 2006;25(6):647–58.

Leigh A. Does child gender affect marital status? evidence from Australia. J Popul Econ. 2009;22(2):351–66.

Lee J. Sibling size and investment in children’s education: an Asian instrument. J Popul Econ. 2008;21(4):855–75.

Li H, Zhang J, Zhu Y. The quantity-quality trade-off of children in a developing country: identification using Chinese Twins. Demography. 2008;45(1):223–43.

Lien H-M, Wu W-C, Lin C-C. New evidence on the link between housing environment and children’s educational attainments. J Urban Econ. 2008;64(2):408–21.

Lin M-J, Liu J-T, Qian N. More missing women, fewer dying girls: the impact of sex-selective abortion on sex at birth and relative female mortality in Taiwan. J Eur Econ Assoc. 2014;12(4):899–926.

Lin T-C. The decline of son preference and rise of gender indifference in Taiwan since 1990. Demogr Res. 2009;20:377–401.

Lloyd CB. Investing in the next generation: the implications of high fertility at the level of the family. In: Cassen R, editor. Population and development: old debates and new conclusions. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers; 1994. p. 181–202.

Maralani V. The changing relationship between family size and educational attainment over the course of socioeconomic development: evidence from Indonesia. Demography. 2008;45(3):693–717.

Mogstad M, Wiswall M. Testing the quantity-quality model of fertility: estimation using unrestricted family size models. Quant Econ. 2016;7(1):157–92.

Oreopoulos P, Page ME, Stevens AH. The intergenerational effects of compulsory schooling. J Labor Econ. 2006;24(4):729–60.

Pollard MS, Morgan SP. Emerging parental gender indifference? sex composition of children and the third birth. Am Sociol Rev. 2002;67(4):600–13.

Qian N. The effect of China’s one child policy on sex selection, family size, and the school enrolment of daughters. Towards Gender Equity Develop. 2018;296:62.

Rosenzweig MR, Wolpin KI. Testing the quantity-quality fertility model: the use of twins as a natural experiment. Econometrica. 1980;48(1):227–40.

Rosenzweig MR, Zhang J. Do population control policies induce more human capital investment? twins, birth weight and China’s “one-child” policy. Rev Econ Stud. 2009;76(3):1149–74.

Sewell WH, Shah VP. Socioeconomic status, intelligence, and the attainment of higher education. Sociol Educ. 1967;40(1):1–23.

Tsou MW, Liu JT, Hammitt JK. The intergenerational transmission of education: evidence from Taiwanese adoptions. Econ Lett. 2012;115(1):134–6.

Funding

This study was not funded by any institution.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We thank participants at the 2016 International Symposium on Human Capital and Labor Markets and the 2018 China Labor Economists Forum for their insights and suggestions on this work. All errors are our own.

Appendix

Appendix

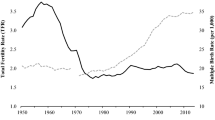

Source: World Bank (https://tradingeconomics.com)

Taiwan’s GDP from 1980 to 2000.

Source: University of Pennsylvania (https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PGDPUSTWA621NUPN)

Purchasing Power Parity Converted GDP Per Capita Relative to the United States, G-K Method, at Current Prices for Taiwan (US = 100).

Source: Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Executive Yuan (https://ceicdata.com/en/taiwan/consumer-price-index-2001,100/cpi-education-and-entertainment-tuition-and-miscellaneous-fees)

Taiwan’s CPI: Education and Entertainment: Tuition and Miscellaneous Fees from 1981 to 2007 (Consumer Price Index: 2001 = 100).

See Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, C., Terrizzi, S., Chou, SY. et al. The effect of sibship size on educational attainment of the first born: evidence from three decennial censuses of Taiwan. Empir Econ 61, 2173–2204 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01930-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01930-3