Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Markers of liver injury, such as alanine aminotransferase (ALT), have been associated with atherogenic lipoprotein changes. We examined the extent to which this association was explained by insulin resistance, adiposity, glucose tolerance and chronic inflammation.

Methods

In this analysis we included 824 non-diabetic participants (age 40–69 years) in the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. No participants reported excessive alcohol intake or treatment with lipid-lowering medications. Lipoproteins and apolipoproteins were measured by conventional methods and lipoprotein heterogeneity by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy.

Results

ALT had a positive relationship with triacylglycerols, LDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio and apolipoprotein B (ApoB) after adjusting for demographic variables (p < 0.001 for all three relationships). ALT was also associated with the following NMR lipoproteins: positively with large VLDL (p < 0.001), intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) (p < 0.001) and small LDL subclass particles (p < 0.001), and VLDL particle size (p < 0.001); and negatively with large LDL subclass particles (p < 0.05) and LDL (p < 0.001) and HDL particle sizes (p < 0.01). ALT remained associated with IDL and small LDL subclass particles and ApoB after adjusting for glucose tolerance, adiposity, directly measured insulin sensitivity and C-reactive protein.

Conclusions/interpretation

ALT is associated with a wide range of atherogenic lipoprotein changes, which are partially explained by insulin resistance, adiposity, glucose tolerance and chronic inflammation. Because of the significant variability in the relationship between ALT and liver fat, further studies are needed to assess the extent of the lipoprotein changes using a direct measure of liver fat.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic liver disease is a major cause of morbidity in the US population [1]. The epidemiology of chronic liver disease is rapidly changing. Viral and alcoholic hepatitis account for a significant number of cases, but the larger proportion is attributable to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) (75.1% of all cases using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2008) [2]. The clinical relevance of NAFLD is not limited to liver-related complications [3], but the relationship between NAFLD, cardiovascular disease and mortality is controversial [4–6]. This is so in part because of the differences between studies in terms of participants (elderly vs younger individuals), study design (cohort of individuals with NAFLD vs epidemiological studies) and criteria for exclusion (e.g. individuals who have elevated liver enzymes).

NAFLD may be considered a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Markers of liver injury including alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and γ-glutamyltransferase (GGT) have been shown to predict future diabetes [7, 8] and metabolic syndrome [9] independently of other risk factors. Measures of liver fat content and markers of liver injury have been associated with insulin resistance [10–13], overall and central adiposity [10–14], decreased adiponectin [10, 13], inflammation [14], and worsening insulin action on glucose and lipid metabolisms [10]. Measures of liver fat content and markers of liver injury have also been associated with dyslipidaemia including high triacylglycerols [10, 13, 15, 16], low HDL-cholesterol [10, 12–14, 16, 17], and increased VLDL particles [12], apolipoprotein B (ApoB) [12, 18] and apolipoprotein B-to-apolipoprotein A-1 ratio (ApoB-to-ApoA-1 ratio) [19]. However, none of these studies adjusted their results for insulin resistance, regional adiposity and glucose tolerance.

The conventional lipid panel may be insufficient to demonstrate the complete range of lipoprotein abnormalities in individuals with mildly elevated ALT. More sophisticated techniques such as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [20] have been used to analyse lipoprotein heterogeneity in insulin resistance and adiposity [21]. Lipoprotein heterogeneity has been associated with carotid intima–media thickness [22], incident cardiovascular disease [23] and incident type 2 diabetes [24]. However, it is not known to what extent insulin resistance, adiposity, glucose tolerance and chronic inflammation explain the relationship between ALT, lipoproteins and apolipoproteins. Therefore, we examined lipoproteins, apolipoproteins and lipoprotein heterogeneity as a function of ALT in non-diabetic participants in the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). ALT appears to be an appropriate marker for estimating liver fat in epidemiological studies. ALT has been shown to have a moderate to strong correlation with liver fat measured by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (r = 0.46 in women and 0.62 in men) [14, 25].

Methods

Study population

The IRAS is a large epidemiological study conducted at four clinical centres in the USA (Los Angeles, CA; Oakland, CA; San Antonio, TX; and the San Luis Valley, CO) to investigate the relationships between insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. We enrolled 1,625 men and non-pregnant women from three ethnic groups (Hispanics, African–Americans and non-Hispanic whites) from 1992 through 1994. All participants provided written informed consent as approved by their respective centre’s institutional review board.

This study includes data on non-diabetic participants in the IRAS (n = 824). Reasons for participant exclusion in the analysis were the following: diabetes (n = 559), treatment with lipid-lowering medications (n = 110), excessive alcohol intake (n = 55), missing information on ALT or lipoproteins (n = 71), and ALT values three or more times above the normal range (n = 6). Information on glucose tolerance was available for all participants, and information on insulin sensitivity index (S I) for 792 of them.

Assessment of glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity

A full description of the study has been previously published [26]. Briefly, the IRAS protocol required two visits, 1 week apart, of approximately 4 h each at baseline. Participants were asked prior to each visit to fast for 12 h, to abstain from heavy exercise and alcohol for 24 h and to refrain from smoking on the morning of the examination. Age, sex, race/ethnicity, pharmacological treatment and alcohol intake were assessed by self-report. Anthropometric variables were measured using standard protocols. During the first visit, a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test was administered and blood was drawn immediately before and 2 h after the glucose load for repeat measurements of glucose and insulin concentrations. During the second baseline visit, insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion were determined using the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test with two modifications to the original protocol [27]. Insulin sensitivity, expressed as the S I, was calculated using mathematical modelling methods (MINMOD version 3.0 [1994]; Los Angeles, CA, USA). Acute insulin response (AIR) was calculated as the mean of 2 min and 4 min insulin concentrations after glucose administration.

Laboratory procedures

We used a glucose oxidase technique on an automated autoanalyser (Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH, USA) to measure plasma glucose (interassay CV 3.2%) and a dextran-coated charcoal radioimmunoassay to determine insulin concentration (interassay CV 19%) [28]. The insulin assay displayed a high degree of cross-reactivity with proinsulin.

Total, LDL- and HDL-cholesterol were measured in plasma by the β-quantification procedure as described by the Lipid Research Clinics at the central IRAS laboratory (Medstar Laboratory, Washington, DC, USA) [29]. VLDL was isolated by preparative ultracentrifugation, and the VLDL (top) and bottom fractions were measured for cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations. HDL-cholesterol was measured after precipitation of ApoB-containing lipoproteins with MnCl2 and heparin. The cholesterol content in the supernatant fraction was measured in a separate autoanalyser channel set to measure low cholesterol values. LDL-cholesterol was calculated as the difference between the HDL-cholesterol and the bottom cholesterol. Triacylglycerols were measured by enzymatic methods with the use of glycerol blanked assays on a Hitachi autoanalyser (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA) [29]. Interassay CV was 4% for LDL-cholesterol, HDL-cholesterol and triacylglycerols. Plasma total ApoB concentrations were assayed with an immunoprecipitation technique (SPQ kit from Incstar Stillwater, MN, USA) and ApoA-I concentrations with a very sensitive ELISA assay at Medstar Laboratory [28]. Lower limits of detection for both ApoB and ApoA-I assays were 5 ng/ml and the interassay CV was 4.1%.

Lipoprotein subclass particle concentrations and average and VLDL, LDL and HDL particle diameters were measured by NMR spectroscopy (LipoScience, Raleigh, NC, USA) [20, 21]. In brief, the NMR signal of each subpopulation differs only slightly in frequency and line shape from the signals of neighbouring subpopulations. Measurement reproducibility of the individual signal amplitudes is inherently limited. To overcome this limitation, neighbouring subpopulations were grouped empirically into a smaller number of subclass categories (large, medium and small) so that the summed amplitudes of the individual subpopulation signals gave acceptable measurement precision (CV <10%). VLDL and LDL subclass particle concentrations are given in units of nanomoles per litre and those of HDL subclasses in micromoles per litre. Weighted-average VLDL, LDL and HDL particle sizes (in nanometres) were calculated as the sum of the diameter of each subclass multiplied by its relative mass percentage. The following subclasses were measured: large VLDL (including chylomicrons if present) (>60 nm), medium VLDL (35–60 nm), small VLDL (27–35 nm), intermediate-density lipoprotein (IDL) (23–27 nm), large LDL (21.2–23 nm), small LDL (18–21.2 nm), large HDL (8.8–13 nm), medium HDL (8.2–8.8 nm) and small HDL (7.3–8.2 nm). CVs <4% were observed for total VLDL, LDL and HDL particle concentrations: <2% for VLDL size; <0.5% for LDL and HDL size; <10% for large, medium and small VLDL subclasses; <8% for large and small LDL subclasses; and <5% for large and small HDL subclasses. Higher CVs for IDL (<20%) and medium HDL (<35%) subclasses reflect their typically low concentrations [21].

ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were measured at the central IRAS laboratory with a Paramax PLA instrument (Baxter, Deerfield, IL, USA). ALT and AST were determined by enzymatic colorimetric assay using standard reagents by reaction rate assay based on the conversion of the reduced form of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide to nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (interassay CV <7%) [30]. One participant had an undetectable ALT concentration (range 0–1.47 μkat/l), but none had an undetectable AST concentration (range 0.10–1.49 μkat/l). C-reactive protein was measured by in-house ultrasensitive competitive immunoassay (antibodies and antigens from Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) with an interassay CV of 8.9% [31].

Variable definition

We considered excessive alcohol consumption an intake of more than two drinks (28 g of alcohol) per day in men and more than one drink (14 g of alcohol) per day in women. Diabetes was defined as fasting glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l, 2 h plasma glucose ≥11.1 mmol/l and/or treatment with glucose-lowering medications. In individuals without diabetes, impaired glucose tolerance (IGT) was defined as 2 h plasma glucose between 7.8 and 11.0 mmol/l. We used BMI ≥30 kg/m2 as the criterion for obesity and the definition of the metabolic syndrome by the 2005 International Diabetes Federation (IDF) to compute the NAFLD liver fat score [32]. Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as follows: HOMA-IR = fasting insulin (μU/ml) × fasting glucose (mmol/l)/22.5 [33]. We used ALT and the NAFLD liver fat score as surrogate markers of NAFLD [34], and NAFLD fibrosis score and Fibrosis 4 score (FIB-4) as markers of disease severity in NAFLD [35, 36]. NAFLD liver fat score = −2.89 + (1.18 × IDF-defined metabolic syndrome [yes = 1/no = 0]) + (0.45 × diabetes [yes = 2/no = 0]) + (0.15 × fasting insulin [mU/l]) + (0.04 × AST [U/l]) − (0.94 × AST [U/l]/ALT [U/l]) [34]. An NAFLD score value ≥ −0.640 has been shown to predict NAFLD with a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 71%; a score ≥ 1.257 has a sensitivity of 59% and a specificity of 94% [34]. NAFLD fibrosis score = −1.675 + (0.037 × age [years]) + (0.094 × BMI [kg/m2]) + (1.13 × impaired fasting glucose/diabetes [yes = 1/no = 0]) + (0.99 × AST/ALT ratio) − (0.013 × platelet count (109/l]) − (0.66 × albumin [g/dl]) [35]. FIB-4 = age [years] × AST [U/l]/(platelet count [109/l] × (ALT [U/l])0.5) [36].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS statistical software (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). ALT has been shown to have stronger correlations with S I [13] and directly measured liver fat compared with AST [16]. We therefore used ALT as the marker of chronic liver injury.

We examined demographic and metabolic variables by quartiles of ALT using one-way analysis of covariance or logistic regression analyses. We assessed the strength of the relationship of ALT to lipoproteins, apolipoproteins and other metabolic variables by linear regression analysis. Log e -transformed values of ALT, AST, triacylglycerols, fasting insulin, AIR, HOMA-IR and C-reactive protein were used to meet the assumptions of the test. Log e transformation of (S I + 1) and (alcohol intake + 1) were also used given that some participants had S I = 0 and alcohol intake = 0 (5.6% and 46.8% of eligible participants, respectively). All probability values were two-sided. We considered a p value <0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

Among non-diabetic participants in the IRAS, rates of obesity, IGT and the metabolic syndrome were 28.9%, 30.1% and 40.1%, respectively. In addition, 38.9% and 16.9% of the participants had NAFLD liver fat scores ≥ −0.640 and ≥ 1.257, respectively.

Table 1 presents the relationship between markers of liver fat, liver fibrosis, insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, adiposity and dyslipidaemia. The NAFLD liver fat score had a strong relationship with ALT, fasting insulin and S I; a moderate relationship with BMI; and a weak relationship with AIR, triacylglycerols and HDL-cholesterol. NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4 had a negative relationship with ALT and were more weakly related to measures of insulin resistance, insulin secretion, adiposity and dyslipidaemia than was ALT. Correlation coefficients relating ALT to measures of insulin sensitivity, insulin secretion, adiposity and dyslipidaemia were lower than the corresponding coefficients of the NAFLD liver fat score. However, we chose ALT as the surrogate measure of liver fat, because the metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance were used to estimate the NAFLD liver fat score and thus could have had a confounding effect on the relationship between NAFLD liver fat score and dyslipidaemia.

Mean values of ALT and AST were 0.31 μkat/l (range 0–1.47) and 0.38 μkat/l (range 0.10–1.49), respectively. Compared with non-Hispanic whites, African–Americans had higher age- and sex-adjusted ALT (0.33 ± 0.02 vs 0.27 ± 0.01 μkat/l; p < 0.001) and AST values (0.37 ± 0.01 vs 0.34 ± 0.01 μkat/l; p = 0.002), but Hispanics had similar ALT (0.26 ± 0.01 μkat/l; p = 0.784) and AST values (0.35 ± 0.01 μkat/l; p = 0.224). Individuals with IGT had higher age-, sex- and race/ethnic-adjusted ALT values than did those with normal glucose tolerance (0.30 ± 0.01 vs 0.27 ± 0.01 μkat/l; p = 0.009), but similar AST values (0.36 ± 0.01 vs 0.35 ± 0.01 μkat/l; p = 0.174).

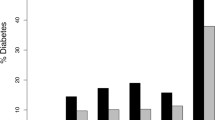

ALT was positively related to BMI, waist circumference, fasting and 2 h glucose, fasting insulin, HOMA-IR, C-reactive protein, NAFLD liver fat score, LDL-cholesterol, LDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio, triacylglycerols, ApoB and ApoB-to-ApoA-1 ratio after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity and clinic (Table 2). ALT was negatively related to age, S I, HDL-cholesterol, NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4. ALT had no significant relationship with alcohol intake (in the truncated distribution of the intake), total cholesterol or ApoA-1. NMR spectroscopy uncovered additional associations for ALT: positive relationships with total VLDL particles, large and small VLDL subclass particles, total LDL particles, IDL and small LDL subclass particles, and VLDL particle size; and inverse relationships with large LDL and large HDL subclass particles, and LDL and HDL particle sizes. Figure 1 presents the relative magnitude of the change in lipoproteins and apolipoproteins across ALT categories.

(a–f) Relative change of lipoproteins, apolipoproteins and lipoprotein composition across ALT quartiles. All results adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnic origin and clinic. Range of ALT within each quartile was as follows: first quartile 0–0.17 μkat/l; second quartile 0.18–0.25 μkat/l; third quartile 0.26–0.37 μkat/l; fourth quartile 0.38–1.47 μkat/l. The first quartile (ALT 0–0.17 μkat/l) was used as the referent category. C, cholesterol

We fitted a multiple linear regression model to data with ALT as the dependent variable and age, sex, race/ethnicity, clinic, IGT, alcohol intake and waist circumference as independent variables (Table 3). Age, sex and waist circumference were the only variables that had independent associations with ALT. Because of the close relationship between central adiposity, insulin sensitivity and liver fat, we added S I and AIR as independent variables in a second model. S I explained the relationship between waist circumference and ALT. Finally, the relationship of metabolic syndrome and C-reactive protein to ALT was assessed in a third model. Both S I and metabolic syndrome had an independent relationship with ALT. This model explained 27.2% of the ALT variance.

We also fitted additional multiple linear regression models to data with individual lipoproteins and apolipoproteins as the dependent variable and age, sex, race/ethnicity, clinic, alcohol intake and ALT as independent variables (Table 4). ALT was directly associated with total and LDL-cholesterol, LDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio, triacylglycerols, ApoB and ApoB-to-ApoA-1 ratio. ALT was also related to the following NMR lipoproteins: directly to large and small VLDL subclass particles, total LDL particles, IDL and small LDL subclass particles, and VLDL particle size; and inversely to large LDL subclass particles and LDL and HDL particle sizes (model 1). However, only the relationship of ALT to IDL and small LDL subclass particles and ApoB remained significant after adjusting for glucose tolerance, waist circumference and S I (model 2). The additional adjustment for C-reactive protein had no significant impact on these relationships (model 3). In models that had the metabolic syndrome as a covariate, ALT was associated with IDL and small LDL subclass particles, VLDL and LDL particle sizes, and ApoB (model 4). The relationship between ALT and IDL subclass particles and ApoB remained statistically significant even after the additional adjustment for waist circumference, glucose tolerance, S I and C-reactive protein (model 5).

In multiple linear regression models with individual lipoproteins and apolipoproteins as the dependent variable and age, sex, race/ethnicity, clinic, alcohol intake and ALT as independent variables, we assessed heterogeneity by introducing interaction terms sex × ALT, or ethnicity × ALT. We detected no p value reaching statistical significance for interaction terms sex × ALT. This indicates that sex had no significant effect on the relationship between ALT and each individual lipoprotein and apolipoprotein. However, ethnicity had a significant interaction effect on the relationship of ALT to triacylglycerol (p = 0.022) and total VLDL particles (p = 0.043). Figure 2 presents the relationship of ALT to S I, ApoB, total LDL particles and small LDL subclass particles by sex, race/ethnicity and obesity (BMI <30 and ≥30 kg/m2). ALT had a statistically significant relationship with S I and ApoB in all categories and with total LDL particles and small LDL subclass particles in all but non-Hispanic whites.

Heterogeneity analyses on the relationship of ALT (independent variable) to S I, ApoB, small LDL and total LDL (dependent variable). Age, sex, race/ethnicity, clinic and alcohol consumption were also included as covariates in all models. Heterogeneity was assessed by introducing interaction terms sex × ALT, ethnicity × ALT, or obesity × ALT

Discussion

In non-diabetic individuals, ALT has direct relationships with triacylglycerols, LDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio, ApoB, and ApoB-to-ApoA-1 ratio after adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, clinic and alcohol intake. Analysis of lipoprotein heterogeneity by NMR spectroscopy reveals additional associations: (1) ALT is directly related to large and small VLDL subclass particles, total LDL particles, IDL and small LDL subclass particles, and VLDL particle size; and (2) ALT is inversely related to large LDL and large HDL subclass particles and LDL and HDL particle sizes. The relationship of ALT to ApoB and IDL and small LDL subclass particles is independent of the effect of insulin sensitivity, central adiposity and glucose tolerance.

NAFLD is a feature of the metabolic syndrome and denotes hepatic insulin resistance [10, 14, 37]. Liver fat content measured by proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy partially explains the variation in triacylglycerols, HDL-cholesterol and insulin concentrations independently of the effect of intra-abdominal and overall adiposity [14]. Individuals with NAFLD have increased cholesterol synthesis [38] and overproduction of large VLDL subclass particles and ApoB [12, 39]. Overproduction of VLDL particles results in the generation of small, dense LDL subclass particles and low HDL-cholesterol, all of which are characteristic traits of individuals with type 2 diabetes [12].

Multiple studies have described significant relationships between liver fat content, or markers of liver injury such as ALT and GGT, and lipoproteins (triacylglycerols, HDL-cholesterol and large VLDL particles) [10, 12–14, 16, 17] and apolipoproteins (ApoB and ApoB-to-ApoA-1 ratio [12, 18, 19]. However, few studies have adjusted their results for regional adiposity, glucose tolerance or insulin resistance. Since ALT and insulin resistance are both related to dyslipidaemia, an unresolved issue is to establish the independent effect of liver fat on lipoproteins and apoliproteins. ALT and GGT have been associated with triacylglycerols after adjusting for fasting insulin, glucose tolerance status and adiposity [40]. ALT has also been associated with high triacylglycerol and/or low HDL-cholesterol concentrations after taking into account the effect of the other metabolic syndrome-related disorders [41]. Lifestyle intervention and treatment with rimonabant have also been shown to reduce liver fat content, adiposity and dyslipidaemia in individuals with and without diabetes [42, 43].

Our present study is in agreement with previous reports that have used conventional methods to measure dyslipidaemic abnormalities following liver fat accumulation. Specifically, ALT has been associated with triacylglycerols, LDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio, ApoB, and ApoB-to-ApoA-1 ratio in non-diabetic individuals. However, our study has novel findings: (1) the relationships of ALT with triacylglycerols, LDL-to-HDL-cholesterol ratio and ApoB are not fully explained by glucose tolerance and central adiposity; and (2) the association between ALT and ApoB is not explained by a direct measure of insulin sensitivity. ApoB reflects the total number of atherogenic particles (VLDL, IDL and LDL subclass particles), but LDL particles usually contribute to more than 90% of the total amount of ApoB [44]. The production of ApoB is increased in individuals with NAFLD [12]. Our study differs somewhat from previous reports by disclosing a weak relationship between ALT and HDL-cholesterol (see the non-linear relationship by quartiles in Table 2). The absence of a relationship between ALT and ApoA-1, the major apolipoprotein of HDL particles, suggests that liver fat may have a small influence on reverse cholesterol transport and protection against the atherosclerotic process (both of which are key functions of HDL-cholesterol particles and ApoA-1) [45].

Sophisticated techniques such as NMR spectroscopy have been helpful in assessing lipoprotein heterogeneity in insulin-resistant states including obesity [20]. Weight loss induced by rimonabant has been associated with a reduction in liver fat and small LDL subclass particles and an increase in large LDL subclass particles and LDL and HDL particle sizes [43]. Our results further expand the extent of lipoprotein changes using ALT as a surrogate marker of liver injury. ALT is directly related to large and small VLDL subclass particles, VLDL particle size, total LDL particles, and IDL and small LDL subclass particles. ALT is inversely related to large LDL subclass particles and LDL and HDL particle sizes. Insulin resistance, central adiposity and liver fat appear to have distinct effects on the relationship of ALT to lipoprotein composition [46]. These relationships are partially explained by insulin resistance, central adiposity and glucose tolerance except for those involving IDL and small LDL subclass particles. Thus, high IDL and small LDL subclass particles as well as high ApoB may be characteristics of individuals with mildly elevated ALT.

Intra-abdominal fat may account for ethnic differences in liver fat [47]. African–Americans tend to have less intra-abdominal fat, liver fat and insulin sensitivity compared with non-Hispanic whites. In our study, African–Americans had higher ALT levels in comparison with non-Hispanic whites and Hispanics. This is probably due to the lower insulin sensitivity in African–Americans compared with the other two populations. Central adiposity and insulin sensitivity largely explain ethnic differences in ALT.

ALT is an imperfect measure of NAFLD and not one that may be suitable for clinical decision making. A better measure is desirable, but it is not available in the IRAS. However, ALT has been shown to correlate well with directly measured liver fat by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (r = 0.46 in women and 0.62 in men [14], making ALT appropriate for estimating liver fat in epidemiological studies [25]. The IRAS and other studies have shown that ALT correlates with direct measures of insulin resistance and sensitivity and measures of dyslipidaemia [11, 48] to predict future development of the metabolic syndrome [9] and type 2 diabetes [7, 48]. In search of a better measure, we have examined the NAFLD liver fat score (a measure of liver fat) and the NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4 (both indices of fibrosis in NAFLD). An NAFLD liver fat score of ≥−0.640 is considered optimal for detecting individuals with NAFLD and is quite prevalent in non-diabetic participants in the IRAS. However, the NAFLD liver fat score may not be the most suitable surrogate measure to analyse the relationship between NAFLD and dyslipidaemia. The NAFLD liver fat score formula includes both fasting insulin (a measure of insulin resistance) and the metabolic syndrome (a clustering of risk factors including triacylglycerol and HDL-cholesterol levels). Therefore, the relationship between NAFLD liver fat score and dyslipidaemia may be driven by the relationship that lipoproteins have with insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome.

Similarly, surrogate indices of fibrosis in individuals with NAFLD do not appear appropriate for studying the relationship between NAFLD and dyslipidaemia. The NAFLD fibrosis score and FIB-4 are inversely related to ALT and more weakly associated with insulin sensitivity and levels of triacylglycerol and HDL-cholesterol than is ALT. In individuals with biopsy-proven NAFLD, high Kleiner scores (the gold standard to assess disease severity in NAFLD) are associated with lower cholesterol and triacylglycerol concentrations compared with low Kleiner scores [49]. Surrogate markers of liver fibrosis may indicate severity of the disease in NAFLD, but the development of liver fibrosis may have consequences for lipoprotein concentration and composition beyond those of liver fat.

Major strengths of our study include the use of data from a large, well-characterised multiethnic cohort of US adults, assessment of glucose tolerance, and measurement of insulin sensitivity by a direct method and lipoprotein heterogeneity by NMR spectroscopy. Our study has also several limitations. It lacks information on directly measured liver fat and GGT and has no information on serology for hepatitis B and C or severity of NAFLD. However, our results also indicate that the relationship of ALT with lipoprotein and apolipoprotein abnormalities is consistent across sex and race/ethnic categories.

In summary, NMR spectroscopy expands the range of atherogenic lipoprotein changes that conventional methods detect in individuals with mildly elevated ALT. The relationship between ALT and lipoprotein composition is partially explained by insulin resistance, adiposity and glucose tolerance status. Because of the significant ALT variability with changes in liver fat, studies with data on directly measured liver fat are needed to assess the extent of the lipoprotein changes in NAFLD.

Abbreviations

- AIR:

-

Acute insulin response

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- Apo:

-

Apolipoprotein

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- FIB-4:

-

Fibrosis 4 score

- GGT:

-

γ-Glutamyltransferase

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- IDF:

-

International Diabetes Federation

- IDL:

-

Intermediate-density lipoprotein

- IGT:

-

Impaired glucose tolerance

- IRAS:

-

Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study

- NAFLD:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- S I :

-

Insulin sensitivity index

References

Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B (2010) Deaths: final data for 2007. Natl Vital Stat Rep 58:19

Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M et al (2011) Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:524–530

Mulhall BP, Ong JP, Younossi ZM (2002) Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an overview. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 17:1136–1143

Schindhelm RK, Dekker JM, Nijpels G et al (2007) Alanine aminotransferase predicts coronary heart disease events: a 10-year follow-up of the Hoorn Study. Atherosclerosis 191:391–396

Ford I, Mooijaart SP, Lloyd S et al (2011) The inverse relationship between alanine aminotransferase in the normal range and adverse cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular outcomes. Int J Epidemiol 40:1530–1538

Lazo M, Hernaez R, Bonekamp S et al (2011) Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and mortality among US adults: prospective cohort study. BMJ 343:d6891

Hanley AJ, Williams K, Festa A et al (2004) Elevations in markers of liver injury and risk of type 2 diabetes: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes 53:2623–2632

Lee DH, Ha MH, Kim JH et al (2003) Gamma-glutamyltransferase and diabetes—a 4 year follow-up study. Diabetologia 46:359–364

Hanley AJ, Williams K, Festa A, Wagenknecht LE, D'Agostino RB Jr, Haffner SM (2005) Liver markers and development of the metabolic syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes 54:3140–3147

Marchesini G, Brizi M, Bianchi G et al (2001) Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a feature of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 50:1844–1850

Hanley AJ, Wagenknecht LE, Festa A, D’Agostino RB Jr, Haffner SM (2007) Alanine aminotransferase and directly measured insulin sensitivity in a multiethnic cohort: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care 30:1819–1827

Adiels M, Taskinen MR, Packard C et al (2006) Overproduction of large VLDL particles is driven by increased liver fat content in man. Diabetologia 49:755–765

Kelley DE, McKolanis TM, Hegazi RA, Kuller LH, Kalhan SC (2003) Fatty liver in type 2 diabetes mellitus: relation to regional adiposity, fatty acids, and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285:E906–E916

Kotronen A, Yki-Järvinen H, Sevastianova K et al (2011) Comparison of the relative contributions of intra-abdominal and liver fat to components of the metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19:23–28

Burgert TS, Taksali SE, Dziura J et al (2006) Alanine aminotransferase levels and fatty liver in childhood obesity: associations with insulin resistance, adiponectin, and visceral fat. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:4287–4294

McKimmie RL, Daniel KR, Carr JJ et al (2008) Hepatic steatosis and subclinical cardiovascular disease in a cohort enriched for type 2 diabetes: the Diabetes Heart Study. Am J Gastroenterol 103:3029–3035

Bethel MA, Deedwania P, Levitt NS et al (2009) Metabolic syndrome and alanine aminotransferase: a global perspective from the NAVIGATOR screening population. Diabet Med 26:1204–1211

Kazumi T, Kawaguchi A, Hirano T, Yoshino G (2006) Serum alanine aminotransferase is associated with serum adiponectin, C-reactive protein and apolipoprotein B in young healthy men. Horm Metab Res 38:119–124

Kelishadi R, Cook SR, Amra B, Adibi A (2009) Factors associated with insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease among youths. Atherosclerosis 204:538–543

Otvos JD (2002) Measurement of lipoprotein subclass profiles by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Clin Lab 48:171–180

Festa A, Williams K, Hanley AJ et al (2005) Nuclear magnetic resonance lipoprotein abnormalities in prediabetic subjects in the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation 111:3465–3472

Lyons TJ, Jenkins AJ, Zheng D et al (2006) Nuclear magnetic resonance-determined lipoprotein subclass profile in the DCCT/EDIC cohort: associations with carotid intima-media thickness. Diabet Med 23:955–966

Mora S, Otvos JD, Rifai N, Rosenson RS, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2009) Lipoprotein particle profiles by nuclear magnetic resonance compared with standard lipids and apolipoproteins in predicting incident cardiovascular disease in women. Circulation 119:931–939

Mora S, Otvos JD, Rosenson RS, Pradhan A, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2010) Lipoprotein particle size and concentration by nuclear magnetic resonance and incident type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes 59:1153–1160

Westerbacka J, Cornér A, Tiikkainen M et al (2004) Women and men have similar amounts of liver and intra-abdominal fat, despite more subcutaneous fat in women: implications for sex differences in markers of cardiovascular risk. Diabetologia 47:1360–1369

Wagenknecht LE, Mayer EJ, Rewers M et al (1995) The insulin resistance atherosclerosis study: design, objectives and recruitment results. Ann Epidemiol 5:464–472

Pacini G, Bergman RN (1986) MINMOD: a computer program to calculate insulin sensitivity and pancreatic responsivity from the frequently sampled intravenous glucose tolerance test. Comput Methods Programs Biomed 23:113–122

Laws A, Hoen HM, Selby JV, Saad MF, Haffner SM, Howard BV (1997) Differences in insulin suppression of free fatty acid levels by gender and glucose tolerance status. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17:64–71

D'Agostino RB Jr, Hamman RF, Karter AJ, Mykkanen L, Wagenknecht LE, Haffner SM (2004) Cardiovascular disease risk factors predict the development of type 2 diabetes: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetes Care 27:2234–2240

Kudoh A, Sakai T, Ishihara H, Matsuki A (1997) Increase in serum creatine phosphokinase concentrations after suxamethonium during sevoflurane or isoflurane anaesthesia in children. Br J Anaesth 78:372–374

Festa A, D’Agostino R Jr, Howard G, Mykkänen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM (2000) Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Circulation 102:42–47

Alberti KG, Zimmet P, Shaw J, IDF Epidemiology Task Force Consensus Group (2005) The metabolic syndrome—a new worldwide definition. Lancet 366:1059–1062

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419

Kotronen A, Peltonen M, Hakkarainen A et al (2009) Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factors. Gastroenterology 137:865–872

Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G et al (2007) The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology 45:846–854

Sterling RK, Lissen E, Clumeck N et al (2006) Development of a simple noninvasive index to predict significant fibrosis in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection. Hepatology 43:1317–1325

Seppälä-Lindroos A, Vehkavaara S, Häkkinen AM et al (2002) Fat accumulation in the liver is associated with defects in insulin suppression of glucose production and serum free fatty acids independent of obesity in normal men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 87:3023–3028

Simonen P, Kotronen A, Hallikainen M et al (2011) Cholesterol synthesis is increased and absorption decreased in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease independent of obesity. J Hepatol 54:153–159

Fabbrini E, Magkos F, Mohammed BS et al (2009) Intrahepatic fat, not visceral fat, is linked with metabolic complications of obesity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 106:15430–15435

Nannipieri M, Gonzales C, Baldi S et al (2005) Liver enzymes, the metabolic syndrome, and incident diabetes: the Mexico City Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 28:1757–1762

Oh SY, Cho YK, Kang MS et al (2006) The association between increased alanine aminotransferase activity and metabolic factors in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism 55:1604–1609

Lazo M, Solga SF, Horska A et al (2010) Effect of a 12-month intensive lifestyle intervention on hepatic steatosis in adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 33:2156–2163

Després JP, Ross R, Boka G, Alméras N, Lemieux I (2009) Effect of rimonabant on the high-triglyceride/low-HDL-cholesterol dyslipidemia, intraabdominal adiposity, and liver fat: the ADAGIO-Lipids trial. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 29:416–423

Walldius G, Jungner I (2005) Rationale for using apolipoprotein B and apolipoprotein A-I as indicators of cardiac risk and as targets for lipid-lowering therapy. Eur Heart J 26:210–212

Brewer HB (2004) Increasing HDL cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 350:1491–1494

D’Adamo E, Northrup V, Weiss R et al (2010) Ethnic differences in lipoprotein subclasses in obese adolescents: importance of liver and intraabdominal fat accretion. Am J Clin Nutr 92:500–508

Guerrero R, Vega GL, Grundy SM, Browning JD (2009) Ethnic differences in hepatic steatosis: an insulin resistance paradox? Hepatology 49:791–801

Vozarova B, Stefan N, Lindsay RS et al (2002) High alanine aminotransferase is associated with decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and predicts the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 51:1889–1895

McPherson S, Stewart SF, Henderson E, Burt AD, Day CP (2010) Simple non-invasive fibrosis scoring systems can reliably exclude advanced fibrosis in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Gut 59:1265–1269

Funding

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grants HL-47887, HL-47889, HL-47890, HL-47892 and HL-47902 and the General Clinical Research Centers Program (NCRR GCRC, M01 RR431 and M01 RR01346).

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

CL contributed to the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article, and gave final approval of the version to be published. AJH contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published. MJR contributed to the acquisition of data, revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published. SMH contributed to the acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data and drafting the article, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lorenzo, C., Hanley, A.J., Rewers, M.J. et al. The association of alanine aminotransferase within the normal and mildly elevated range with lipoproteins and apolipoproteins: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study. Diabetologia 56, 746–757 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2826-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2826-4