Abstract

Background Recent studies have suggested that there has been an increase in the number of ‘warning letters’ issued by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) despite the publication of the FDA advertising guidelines. However, limited information is available on the description of warning letters. The objective of this study was to analyse the frequency and content of FDA warning letters in relation to promotional claims and discuss the influence of regulatory and industry constraints on promotion.

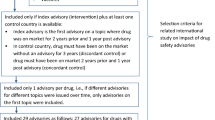

Methods All warning letters published by the FDA between 5 May 1995 and 11 June 2007 were reviewed. Warning letters related to promotional issues were included and analysed. Information related to the identification number, date of the warning letter, FDA division that issued the letter, drug name, manufacturer, specific warning problem, type of promotional material and requested action was extracted. Two independent investigators reviewed and classified each PDF file, any differences were discussed until a consensus was reached.

Results Between May 1995 and June 2007 a total of 8692 warning letters were issued, of which 25% were related to drugs. Of these, 206 warning letters focused on drug promotion and were included in this study: 23% were issued in 2005, 15% in 2004 and 14% in 1998. In total, 47% of the warning letters were issued because of false or misleading unapproved doses and uses, 27% failed to disclose risks, 15% cited misleading promotion, 8% related to misleading labelling and 3% promoted false effectiveness claims.

Discussion There is an important variation in the number of warning letters issued in the last decade, probably because of the increasing number of drugs approved by the FDA, drug withdrawal scandals, and the publication of the FDA and the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) guidelines.

Conclusion We found that benefit-related claims, such as unapproved uses or doses of drugs, and failure to disclose risks, are the main causes of FDA issued warning letters for promotional claims related to medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The use of trade names is for product identification purposes only and does not imply endorsement.

These can be reported via e-mail to webcomplaints@ora.fda.gov.

References

Kessler DA, Pines WL. The federal regulation of prescription drug advertising and promotion. JAMA 1990; 264: 2409–15

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, 21 CFR Part 310 section 502(a) of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (Modernization Act). 21 U.S.C. 352 (n)

US Food and Drug Administration. Section 502(n) of the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act, and Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations, 202.1(1)(1)

US Food and Drug Administration. Section 502(n) of the Food Drug and Cosmetics Act, and Title 21 Code of Federal Regulations, section 202.1 (j)(1)

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, 21 CFR Part 310 section 502(a) of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (Modernization Act). 21 314.81(b)(3)

Woodcock J (DHHS, FDA). Statement by Janet Woodcock, MSD Director, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. US Drug Administration, Department of Health and Human Services. July 22, 2003 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/ola/2003/AdvertisingofPrescriptionDrugs0722.html [Accessed 2008 Feb 18]

Gahart MT, Duhamel LM, Dievler A, et al. Examining the FDA’s oversight of direct to consumer advertising. Health Aff 2003; W3: 120–3

Enforcement of FDA ad regulations drops precipitously [online]. Available from URL: http://oversight.house.gov/story.asp?ID=441 [Accessed 2007 Jun 1]

Waxman HA. Ensuring that consumers receive appropriate information from drug ads: what is the FDA’s role? Health Aff 2004; W4: 256–8

US Food and Drug Administration. Advertising/labeling definitions [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/handbook/adverdef.htm [Accessed 2007 Dec 1]

Berndt ER. Pharmaceuticals in U.S. health care: determinants of quantity and price. J Econ Perspect 2002 Fall; 16 (4): 45–66

Halperin RM. FDA disclosure of safety and effectiveness data: a legal and policy analysis. Duke Law J 1979 Feb; 1: 286–326

Tansey B. Hard sell: how marketing drives the pharmaceutical industry: a patient’s right to know. How much should doctors disclose about treatments not approved by the FDA? San Fran Chronicle 2005 May 1 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.sfgate.com [Accessed 2005 Jun 24]

Steinman MA, Bero LA, Chren MM, et al. Narrative review: the promotion of gabapentin: an analysis of internal industry documents. Ann Intern Med 2006; 145: 284–93

US Department of Justice. Warner-Lambert to pay $430 million to resolve criminal and civil health care liability relating to off-label promotion. 2004 May 13 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.usdoj.gov/opa/pr/2004/May/04_civ_322.htm [Accessed 2007 Aug 30]

Oregon Attorney General files judgment with Purdue Pharma over marketing of Oxycontin [online]. Available from URL: http://www.allamericanpatriots.com/48722692_oregon_oregon_attorney_general_files_judgment_purdue_pharma_over_marketing_oxycontin [Accessed 2007 Sept 6]

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: consumer-directed broadcast advertisements. Washington, DC: Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, FDA, 1999 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/CDER/guidance/1804fnl.htm [Accessed 2008 Feb 18]

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry: using FDA-approved patient labeling in consumer-directed print advertisements. Draft guidance. 2001 Apr [online]. Available from URL: http://www.bcg-usa.com/docs/2001/FDA200104B.pdf [Accessed 2008 Feb 18]

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA sees rebound in approval of innovative drugs in 2003: new innovation initiative anticipated to speed approvals in years ahead. Press release 2004 Jan 15 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/NEWS/2004/NEW01005.html [Accessed 2008 Jan 2]

Abenhaim L. Lessons from the withdrawal of rofecoxib. BMJ 2004; 329: 867–8

A taste of new medicine. Nature Med 2006; 12: 481

Norman P. Generic competition 2007 to 2011: the impact of patent expiries on sales of major drugs. London: Urch Publishing, 2007

US Food and Drug Administration. Draft guidance for industry on good reprint practices for the distribution of medical journal articles and medical or scientific reference publications on unapproved new uses of approved drugs and approved or cleared medical devices: availability [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/98fr/08-746.pdf [Accessed 2008 Mar 5]

Ziegler MG, Lew P, Singer BC. The accuracy of drug information from pharmaceutical sales representatives. JAMA 1995; 273: 1296–8

Dana J, Loewenstein G. A social science perspective on gifts to physicians from industry. JAMA 2003; 290: 252–5

Tiner R. Reasons for not seeing drug representatives. BMJ 1999; 319: 1002

Thomson AN, Craig BJ, Barham PM. Attitudes of general practitioners in New Zealand to pharmaceutical representatives. Br J Gen Pract 1994; 44: 220–3

Benbow AG. Reasons for not seeing drug representatives. BMJ 1999; 319: 1003

Croasdale M. Some medical schools say no to drug reps’ free lunch. Stanford, Yale and the University of Pennsylvania have adopted policies to create a brighter line between medicine and marketing. Am Med News 2006 Oct 9 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.ama-assn.org [Accessed 2007 Aug 31]

Brennan TA, Rothman DJ, Blank L, et al. Health industry practices that create conflicts of interest: a policy proposal for academic medical centers. JAMA 2006; 295: 429–33

US Food and Drug Administration, CDER. Over-the-counter drug products [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/handbook/otcintro.htm [Accessed 2008 Mar 5]

US Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. 2001 Report to the nation improving public health through human drugs [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/reports/rtn/2001/rtn2001.pdf [Accessed 2008 Mar 5]

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Over-the-counter human drugs; labeling requirements; final rule; technical amendment. Fed Reg 2000 Jan 3; 65 (1): 7–8

US Food and Drug Administration. US Food and Drug Administration. Compliance program guidance manual. 2002 Jun 1 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/dmpq/CPGM_7361-003_OTC1.pdf [Accessed 2008 Mar 5]

Caplovitz A. Turning medicine into snake oil: how pharmaceutical marketers put patients at risk. NJPIRG Law and Policy Center. 2006 May 1 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.njpirg.org [Accessed 2008 Feb 18]

Almasi EA, Stafford RS, Kravitz RL, et al. What are the public health effects of direct-to-consumer drug advertising? PLoS Med 2006; 3: 284–8

Vaithianathan R. Better the devil you know than the doctor you don’t: is advertising drugs to doctors more harmful than advertising to patients? J Health Serv Res Policy 2006; 11: 235–9

US Food and Drug Administration. Reporting unlawful sales of medical products on the internet [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/oc/buyon-line/buyonlineform.htm [Accessed 2007 Aug 1]

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA’s mission statement [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/opacom/morechoices/mission.html [Accessed 2007 Jun 10]

CDER, Division of Drug Marketing, Advertising, and Communications, Food and Drug Administration. Description [online]. Available from URL: http://www.fda.gov/cder/ddmac/ [Accessed 2007 May 31]

US Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration, 21 CFR Part 310 Sect. 502(a) of the Food and Drug Administration Modernization Act of 1997 (Modernization Act). 21 U.S.C. 352 (a)

Baylor-Henry M, Drezin NA. Regulation of prescription drug promotion: direct-to consumer advertising. Clin Ther 1998; 20 Suppl. C: C86–95

Acknowledgements

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study. The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salas, M., Martin, M., Pisu, M. et al. Analysis of US Food and Drug Administration Warning Letters. Pharm Med 22, 119–125 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256691

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03256691