Abstract

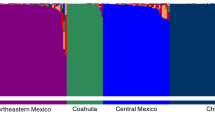

Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) loci were used to investigate the origin and genetic relationships of the domesticated sunflower and its wild relatives. A total of 13 primers was employed for the PCR amplifications, from which 68 polymorphic loci were scored. Analysis of RAPD data supports the origin of the domesticated sunflower from wildH. annuus. The high RAPD identity between wild and domesticatedH. annuus (I = 0.976 to I = 0.997) is concordant with a progenitorderivative relationship. However, the identities are very high and therefore provide little information regarding the geographic origin of the domesticated sunflower. Nonetheless, some inferences concerning relationships among domesticated sunflower accessions can be made. The native American varieties and old landracesform a genetically cohesive group based on RAPD evidence, probably due to their origin prior to the use of interspecific hybridization in the development of sunflower cultivars. In contrast, the modern cultivars are not genetically cohesive, perhaps due to the extensive use of intraspecific and interspecific hybridization in the development of modern sunflower varieties. Likewise, little concordance was observed between the geographical origin and genetic clustering of wild populations—an observation probably best explained by the weedy, human dispersed nature of wildH. annuus populations. The information presented here may be a reliable indicator of genetic relationships among wild and domesticated sunflower accessions. However, the processes generating the observed relationships are complex, and the occurrence of unexpected groupings or absence of predicted ones will probably remain difficult to understand.

Abstract

Los loci obtenidos de Polimorfismos de ADN Amplificados al Azar (RAPDs) fueron usados para investigar el origen y las relaciones genéticas del girasol domesticado y de sus parientes silvestres. Un total de trece sequencias primarias fueron utilizadas para las amplificaciones de PCR, de los cuales 68 loci polimórficos fueron muestreados. El análisis de identidades utilizando RAPDs entreH. annuus domesticados y silvestres (de I = 0.976 a I = 0.997) es concordante con el modelo de progenitor-derivado. Sin embargo, los valores de identidad son altos y por lo tanto proveen poca información en relación al origen geográfico del girasol domesticado. Por otro lado, alguna información acerca de las relaciones entre las poblaciones domesticadas pueden hacerse. La evidencia de RAPDs indica que las variedades Americanas nativas y las razas antiguas forman una agrupación genéticamente cohesiva, debido probablemente a que se originaron antes del uso de hibridación interespecífica en el desarrollo de cultivares de girasol. En contraste, los cultivares modernos no sepresentan genéticamente cohesivos, debido quizás al extenso uso de hibridación intraespecífica e interespecífica en el desarrollo de las variedades modernas de girasol; de otra manera, la poca concordancia observada entre el origen geográfico y el agrupamiento genético de las poblaciones silvestres—una observación que probablemente puede ser mejor explicada por la naturaleza malezoide y de dispersión humana que las poblaciones deH. annuus poseen. La información presentada aquí quizás sea un indicador confiable de las relaciones genéticas entre las poblaciones silvestres y domesticadas. Los procesos que han generado las relaciones observadas son complejas. La presencia de agrupaciones inesperadas o la ausencia de agrupaciones predichas en particular pobablemente será difícil de entender.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Cited

Anderson, E. 1952. Plants, man and life. Little Brown, Boston.

Asch, D. L. 1993. Common sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.): the pathway toward domestication. Symposium presentation, 58th Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, St. Louis, MO.

Cockerell, T. D. A. 912. The red sunflower. The Popular Science Monthly, 373–382.

—. 1918. The story of the red sunflowers. American Museum Journal 18:38–47.

Crites, G. D. 1993. Domesticated sunflower in fifth millennium b.p. temporal context: new evidence from middle Tennessee. American Antiquity 58: 146–148.

Dorado, O., L. H. Rieseberg, andD. M. Arias. 1992. Chloroplast DNA introgression between southern California sunflowers. Evolution 46:556–572.

Doyle, J. J., andJ. L. Doyle. 1987. A rapid DNA isolation procedure for small quantities of fresh leaf material. Phytochemical Bulletin 19:11–15.

Felsenstein, J. 1993. PHYLIP, phylogeny inference package, version 3.5c. University of Washington, Seattle.

Fick, G. N. 1978. Breeding and genetics. Pages 279–397in J. F. Carter, ed., Sunflower science and technology. AAS, CSSA, and ASSA, Madison, WI.

Fritsch, P. F., andL. H. Rieseberg. 1992. High outcrossing rates maintain male and hermaphrodite individuals in populations of the flowering plantDatisca glomerata. Nature 359:633–636.

Fritsch, P. F., and L. H. Rieseberg. n.d. The use of random amplified polymorphic DNA in conservation genetics.In T. B. Smith and B. Wayne, eds., Molecular genetic approaches in conservation. Oxford University Press, New York.

Gilmore, M. R. 1913. Some native Nebraska plants with their use by the Dakota. Nebraska State History Society 17:358–370.

Heiser, C. B. 1946. A “new” cultivated sunflower from Mexico. Madroño 8:226–229.

—. 1951. The sunflower among the North American Indians. Proceedings of the American Philosophy Society 95:432–448.

—. 1954. Variation and subspeciation in the common sunflower,Helianthus annuus. American Midland Naturalist 51:287–305.

—. 1978. Taxonomy ofHelianthus and origin of the domesticated sunflower. Pages 31–53in J. F. Carter, ed., Sunflower science and technology. ASA, CSSA, and ASSA, Madison, WI.

—. 1985. Some botanical considerations of the early domesticated plants north of Mexico. Pages 57–72in R. Ford, ed., Prehistoric food production in North America. Anthropology Paper 75. Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

—,D. M. Smith, S. B. Clevenger, and W. C. Martin. 1969. The North American sunflowers (Helianthus). Memoirs of the Torrey Botanical Club 22:1–218.

Lewis, P.O. 1993. GENESTAT-PC 3.3. North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC.

Lynch, M., and B. G. Milligan. 1994. Analysis of population genetic structure with RAPD markers. Molecular Ecology 3:1–20.

Nei, M. 1972. Genetic distance between populations. American Naturalist 106:283–292.

—,F. Tajima, and Y. Tateno. 1983. Accuracy of estimated phylogenetic trees from molecular data. II. Gene frequency data. Journal of Molecular Evolution 19:153–170.

Putt, E. D. 1978. History and present world status. Pages 1–30in J. F. Carter, ed., Sunflower science and technology. ASA, CSSA, and ASSA, Madison, WI.

Rieseberg, L. H. 1991. Homoploid reticulate evolution inHelianthus (Asteraceae): evidence from ribosomal genes. American Journal of Botany 78: 1218–1237.

—,S. Beckstrom-Sternberg, and K. Doan. 1990.Helianthus annuus ssp.texanus has chloroplast DNA and nuclear ribosomal RNA genes ofHelianthus debilis ssp.cucumerifolius. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 87:593–597.

—, —,A. Listen, and D. M. Arias. 1991. Phylogenetic and systematic inferences from chloroplast DNA and isozyme variation inHelianthus sect.Helianthus (Asteraceae). Systematic Botany 16: 50–76.

—,H. Choi, R. Chan, and C. Spore. 1993. Genomic map of a diploid hybrid species. Heredity 70:285–293.

—,M. A. Hanson, and C. T. Philbrick. 1992. Androdioecy is derived from dioecy in Datiscaceae: Evidence from restriction site mapping of PCR-amplified chloroplast DNA fragments. Systematic Botany 17:324–336.

—,and G. J. Seiler. 1990. Molecular evidence and the origin and development of the domesticated sunflower (Helianthus annuus, Asteraceae). Economic Botany (supplement) 44:79–91.

Saitou, N., and M. Nei. 1987. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 4:406–425.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Arias, D.M., Rieseberg, L.H. Genetic relationships among domesticated and wild sunflowers (Helianthus annuus, Asteraceae). Econ Bot 49, 239–248 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862340

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02862340