Abstract

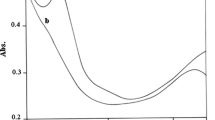

The αβ subunits of the tungsten-containing reversible aldehyde oxidoreductase ofClostridium thermoaceticum were shown to contain a pterin cofactor in the form of a mononucleotide. The substrate specificity of the enzyme for aliphatic and aromatic aldehydes and for carboxylates was broad. TheK m values for ethanal, propanal and butanal were 0.010–0.006 mM, but the value for methanal was 1.6 mM. Benzaldehyde derivatives with a hydroxy group in the 4-position showed millimolarK m values that were2–3 orders of magnitude higher than those of other aromatic and aliphatic aldehydes. The ratio ofk cat/Km for aldehydes and the corresponding acids is 104–105. For carboxylate reduction, 4-hydroxy benzoate again showed the highestK m value of all substrates tested. When the 4-hydroxy groups of the aldehyde and the acid were methylated, theK m values were decreased drastically. From the temperature dependence of carboxylate reduction at the expense of viologens, activation energies that depended on the substrate and on the applied viologen were calculated. The pH optima of the carboxylate reductions depended on the pK values of the acids and shifted to lower pH values with lower pK values of the acids. The ternary complex α3β3γ of the aldehyde oxidoreductase was able to dehydrogenate aldehydes to acylates with NADP+. Surprisingly the reverse reaction was observed too, although at very low rates. When exposed to air, the aldehyde oxidoreductase showed markedly enhanced lability in its reduced state compared to its oxidized state. With resting cells ofC. thermoaceticum, many carboxylates were reduced at the expense of carbon monoxide to the corresponding alcohols.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- AOR :

-

Aldehyde oxidoreductase

- V :

-

Viologen

- CAV :

-

1,1′-Carbamoylmethyl-viologen

- MV :

-

Methyl viologen

- PN :

-

Productivity number

References

Bayer M (1994) Charakterisierung von verschiedenen Redoxenzymen aus Clostridien und ihre präparative Nutzung zur Herstellung chiraler Verbindungen. Dissertation, Technische-Universität, München

Bertram PA, Schmitz RA, Linder D, Thauer RK (1994) Tungstate can substitute for molybdate in sustaining growth ofMethanobacterium thermoautotrophicum: identification and characterization of a tungsten isoenzyme of formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase. Arch Microbiol 161:220–228

Chan MK, Mukund S, Kletzin A, Adams MWW, Rees DC (1995) Structure of a hyperthemophilic tungstopterin enzyme, aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase. Science 267:1463–1469

Daniel SL, Drake HL (1993) Oxalate- and glyoxylate-dependent growth and acetogenesis byClostridium thermoaceticum. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:3062–3069

Dieckert G, Fuchs G, Thauer RK (1985) Properties and function of carbon monoxide dehydrogenase from anaerobic bacteria. Spez Publ Soc Gen Microbiol 14:115–130

Fuchs G (1990) Alternatives to the Calvin cycle and the Krebs cycle in anaerobic bacteria: pathways with carbonylation chemistry. In: Hauska G, Thauer R (eds) The molecular basis of bacterial metabolism. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 13–20

Gößner A, Daniel SL, Drake HL (1994) Acetogenesis coupled to the oxidation of aromatic aldehyde groups. Arch Microbiol 161:126–131

Günther H, Neumann S, Simon H (1987) 2-Oxocarboxylate reductase fromProteus species and its use for the preparation of (2R)-hydroxy acids. J Biotechnol 5:53–65

Huber C, Caldeira J, Jongejan JA, Simon H (1994) Further characterization of two different, reversible aldehyde oxidoreductases fromClostridium formicoaceticum, one containing tungsten and the other molybdenum. Arch Microbiol 162:303–309

Johnson JL, Hainline BE, Rajagopalan KV (1984) The pterin component of the molybdenum cofactor. J Biol Chem 259:5414–5422

Johnson JL, Rajagopalan KV, Mukund S, Adams MWW (1993) Identification of molybdopterin as the organic component of the tungsten cofactor in four enzymes from hyperthermophilic archeae. J Biol Chem 268:4848–4852

Kortüm G, Vogel W, Andrussow K (1961) Dissociation constants of organic acids in aqueous solutions Butterworth, London

Krüger B, Meyer O (1987) Structural elements of bactopterin fromPseudomonas carboxydoflava carbon monoxide dehydrogenase. Biochim Biophys Acta 912:357–364

Krüger B, Meyer O, Nagel M, Andreesen JR, Meincke M, Bock E, Blümle S, Zumft WG (1987) Evidence for the presence of bactopterin in the eubacterial molybdoenzymes nicotinic acid dehydrogenase, nitrite oxidoreductase, and respiratory nitrate reductase. FEMS Microbiol Lett 48:225–227

Loach PA (1976) Physical and chemical data. In: Fasman GD (ed) Handbook of biochemistry and molecular biology (vol 1, 3rd edn). CRC Press, Cleveland, pp 122–130

Mukund S, Adams MWW (1991) The novel tungsten-iron-sulfurprotein of the hyperthermophilic archaebacterium;Pyrococcus furiosus, is an aldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem 266:14208–14216

Mukund S and Adams MWW (1993) Characterization of a novel tungsten-containing formaldehyde ferredoxin oxidoreductase from the hyperthermophilic archaeonThermocccus litoralis. J Biol Chem 268:13592–13600

Ragsdale SW, Clark JE, Ljungdahl LG, Lundie LL, Drake HL (1983) Properties of purified carbon monoxide dehydrogenase fromClostridium thermoaceticum, a nickel, iron-sulfur protein. J Biol Chem 258:2364–2369

Schmitz RA, Richter M, Linder D, Thauer RK (1992) A tungstencontaining active formylmethanofuran dehydrogenase in the the thermophilic archaeonMethanobacterium wolfei. Eur J Biochem 207:559–565

Schulz M, Bayer M, White H, Günther H, Simon H (1994) Application of high enzyme activities present inClostridium thermoaceticum for the efficient regeneration of NADPH, NADP+, NADH and NAD+. Biocatalysis 10:25–36

Schulz M, Leichmann H, Simon, H (1995) Electromicrobial regeneration of pyridine nucleotides and other preparative redox transformations withClostridium thermoaceticum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 42:916–922

Segel JH (1975) Enzyme kinetics. Wiley, New York, pp 665–749; 931–940

Simon H, White H, Lebertz H, Thanos J (1987) Reduktion von 2-Enoaten und Alkanoaten mit Kohlenmonoxid oder Formiat, Viologenen undClostridium thermoaceticum zu gesättigten Säuren und ungesättigten bzw. gesättigten Alkoholen. Angew Chem 99:785–786; Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 26:785–787

Skopan H (1990) Untersuchungen zum Mechanismus der molybdänhaltigen 2-Hydroxycarboxylat-Viologen-Oxidoreduktase ausProteus vulgaris und zur Substratbreite, und Kinetik der wolframhaltigen Carbonsäure Reduktase ausClostridium thermoaceticum. Dissertation Technische Universität, München

Strobl G, Feicht R, White H, Lottspeich F, Simon H (1992) The tungsten-containing aldehyde oxidoreductase fromClostridium thermoaceticum and its complex with a viologen accepting NADPH oxidoreductase. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler 373:123–132

Thanos I, Bader J, Günther H, Neumann S, Krauss F, Simon H (1987) Electroenzymatic and electromicrobial reduction: prepatation of chiral compounds. Methods Enzymol 136:302–317

Trautwein T, Krauss, F, Lottspeich F, Simon H (1994) The (2R)-hydroxycarboxylate-viologen-oxidoreductase fromProteus vulgaris is a molybdenum-containing iron-sulphur protein. Eur J Biochem 222:1025–1032

White H, Strobl G, Feicht R, Simon H (1989) Carboxylic acid reductase: a new tungsten enzyme catalyzes the reduction of nonactivated carboxylic acids to aldehydes. Eur J Biochem 184:89–96

White H, Feicht R, Huber C, Lottspeich F, Simon H (1991) Purification and some properties of the tungsten-containing carboxylic acid reductase fromClostridium formicoaceticum. Biol Chem Hoppe-Seyler 372:999–1005

White H, Huber C, Feicht R, Simon H (1993) On a reversible molybdenum-containing aldehyde oxidoreductase fromClostridium formicoaceticum. Arch Microbiol 159:244–249

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Dedicated to Professor H. J. Bestmann on the occasion of his 70th birthday

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, C., Skopan, H., Feicht, R. et al. Pterin cofactor, substrate specificity, and observations on the kinetics of the reversible tungsten-containing aldehyde oxidoreductase fromClostridium thermoaceticum . Arch. Microbiol. 164, 110–118 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02525316

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02525316