Summary

In a first attempt to explain the evolution of the avian navigational system, Bellrose suggested that compass mechanisms and the ability for true navigation had developed in connection with migration across increasing distances. Yet birds use compasses, the mosaic and the navigational maps even close to home and for homing. This means that those mechanisms must have developed for orientation within the home range, with the necessity to optimize the everyday flights acting as selective pressure. In view of this, any attempt to reconstruct the evolution of the avian navigational system must start out with the non-flying ancestors of birds.

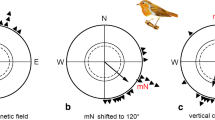

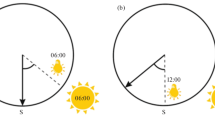

Considering the requirements of orientation by landmarks and by using a compass, compass orientation with the help of the magnetic field appears to be the simplest mechanism; consequently, it must be assumed to belong to the most ancient orientation strategies. The magnetic compass is wide-spread among animals, but it appears to function according to different principles among the various groups of vertebrates so that it is unclear whether birds inherited their magnetic compass from their reptilian ancestors or developed a mechanism of their own. The same is true for the sun compass. The crucial role of the magnetic compass in the ontogenetic development of the sun compass might indicate a similar relationship for the phylogenetic development.

Over short distances within the home range, orientation based solely on compass orientation appears possible, using the strategy of route reversal, with non-straight routes being integrated. Since this strategy accumulates errors, it becomes inaccurate over longer distances, thus causing selective pressure to use local site-specific information. This leads to the formation of the mosaic map, a mechanism that includes landmarks as well as compass orientation. Today, the mosaic map of landmarks is a mechanism by itself, established according to innate learning principles that associate information on path integration with site-specific information, thus forming a directionally oriented mental representation of the distribution of landmarks. The navigational map is formed by applying the same principles to factors of the nature of gradients; it thus appears to have developed from the mosaic map. Whether or not it is a special development of birds associated with their flying ability is unclear. Because the birds probably inherited the basic mechanisms of orientation from their ancestors, one would expect these mechanisms to be similar in all birds. For the mechanisms involving learned components, this means that they are established following common rules. Birds improved those mechanisms and adapted them to their specific needs.

Migration is assumed to have begun with non-directed search movements for regions offering better conditions. At this stage, the already existing mechanisms of homing were sufficient for navigation between the various areas. When these first movements turned into regular migration between two regions, the migratory program began to evolve, starting out with spontaneous tendencies in a preferred direction. The magnetic compass may have served as first reference system for the migratory direction; later, celestial rotation, indicated by the changing pattern of polarized light during the day, obtained its important role in indicating the reference direction geographic South. In the course of time, sophisticated migration programs with changes in direction, controlling time programs, responses to trigger mechanisms etc. developed. The migratory direction and distance, i.e. the amount of migratory activity, continue to be subject to selective pressure so that birds can respond to the environmental conditions in an optimal way. The transition from daytime migration to night migration did not require new mechanisms, as the magnetic compass can be used at any time of the day. Later, however, the star compass evolved, which is to be considered a special development of night-migrating birds, with its way of functioning well adapted to the specific needs of migrants. Birds also developed the ability to derive information on celestial rotation from the rotating stars at night and to transfer this information directly to the star compass. Since migratory habits evolved many times independently among birds, the same has to be assumed for the specific mechanisms of migratory orientation. This means that they need not necessarily be identical in all bird migrants. We are to expect convergent developments, however, leading to mechanisms of the most suitable type.

Zusammenfassung

Ein erster Versuch von Bellrose, die Evolution des Orientierungssystems der Vögel zu beschreiben, ging von der Annahme aus, Kompaßorientierung und die Fähigkeit zur Navigation habe sich im Zusammenhang mit dem Vogelzug entwickelt. Kompaßmechanismen sowie die Mosaik- und die Navigationskarte spielen jedoch bereits bei der Orientierung im Heimbereich entscheidende Rollen, müssen sich also dort entwickelt haben unter dem Selektionsdruck, die täglichen Flugwege zu optimieren, vielleicht schon bei den Vorfahren der Vögel.

Magnetkompaßorientierung erscheint als der einfachste Orientierungsmechanismus und müßte deshalb an den ältesten Orientierungsstrategien beteiligt gewesen sein. Ein Magnetkompaß ist bei Wirbeltieren weit verbreitet, doch gibt es Hinweise auf unterschiedliche Funktionsprinzipien. Es ist deshalb offen, ob die Vögel ihn von ihren Vorfahren übernommen oder eigenständig entwickelt haben. Das gleiche gilt für den Sonnenkompaß. Die entscheidende Rolle des Magnetkompaß bei der ontogenetischen Entwicklung des Sonnenkompaß läßt eine ähnliche Beziehung bei der phylogenetischen Entwicklung vermuten.

Über kurze Entfernungen kann man sich Orientierung durch Wegumkehr allein mit Kompaßmechanismen vorstellen, wobei Umwege integriert werden müssen. Bei dieser Strategie akkumulieren sich jedoch die Fehler; die bei größeren Entfernungen resultierende Ungenauigkeit erzeugte einen Selektionsdruck, der das Benutzen von Ortsinformation begünstigte. Dies führte zur Entstehung der Mosaikkarte, die auf Kompaßorientierung und Landmarken beruht. Sie ist heute als eigenständiger Mechanismus anzusehen, der nach angeborenen Regeln aufgebaut wird. Die Navigationskarte entsteht, indem die gleichen Regeln auf Faktoren mit Gradienten-Charakter angewandt werden; sie hat sich offenbar aus der Mosaikkarte entwickelt. Ob sie eine Sonderentwicklung der Vögel infolge ihrer Flugfähigkeit ist, muß offen bleiben. Da die Vögel die Grundelemente ihres Orientierungssystems wahrscheinlich von ihren Vorfahren übernommen haben, würden wir erwarten, daß diese Mechanismen bei allen Vögel gleich sind bzw. nach den gleichen Regeln erstellt werden.

Vorstufen des Vogelzugs waren zunächst ungerichtete Flüge auf der Suche nach günstigeren Bedingungen; in diesem Stadium reichten die vorhandenen Navigationsmechanismen zur Orientierung zwischen den verschiedenen Gebieten aus. Als aus diesen ersten Ortsbewegungen ein regelmäßiger Zug zwischen zwei Regionen wurde, begann sich das Zugprogramm zu entwickeln, wobei sich zunächst eine spontane Richtungstendenz herausbildete. Der Magnetkompaß konnte als erstes Referenzsystem für diese Zugrichtung dienen. Später erhielt die Himmelsrotation ihre entscheidende Bedeutung, wobei die Vögel die Referenzrichtung Süd zunächst aus dem Polarisationsmuster am Tage ableiteten. Im Laufe der Zeit entstanden die differenzierten Zugprogramme mit Richtungsfolgen, steuernden Zeitprogrammen und Triggermechanismen. Die Zugrichtung und Länge der Zugstrecke unterliegen auch weiterhin einer ständigen Selektion, die für optimale Anpassung an die jeweiligen Umweltbedingungen sorgt. Der Übergang vom Tag- zum Nachtzug bereitete keine Probleme, denn die Vögel mußten zunächst keine neuen Orientierungsmechanismen entwickeln, da sich der Magnetkompaß zu jeder Tageszeit einsetzen läßt. Später entstand der Sternkompaß, der in seinen Funktionseigenschaften hervorragend auf die Bedürfnisse von Zugvögeln angepaßt ist und als eigenständige Entwicklung der Nachtzieher angesehen werden muß. Dazu erwarben die Nachtzieher die Fähigkeit, die Information der Himmelsrotation aus der Bewegung der Sterne abzuleiten und direkt auf den Sternkompaß zu übertragen. Da das Zugverhalten bei Vögeln mehrfach unabhängig voneinander entstanden ist, muß man Entsprechendes auch von den Mechanismen der Zugorientierung annehmen. Das bedeutet, daß sich die betreffenden Mechanismen bei den verschiedenen Arten unterschiedlich entwickelt haben könnten, doch ist mit konvergenten Entwicklungen zu rechnen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literatur

Arbeit I „Kompaßorientierung“: J. Ornithol. 140, 1–40 (1999).

Arbeit II „Heimfinden und Navigation“: J. Ornithol. 140, 129–164 (1999).

Arbeit III „Zugorientierung“: J. Ornithol. 140, 273–308 (1999).

Able, K.P. & Able, M.A. (1993): Daytime calibration of magnetic orientation in a migratory bird requires a view of skylight polarization. Nature 364: 523–525.

Able, K.P. & Able, M.A. (1999): Migratory orientation: learning rules for a complex behavior. In: Adams, N., Slotow, R. (Eds.): Proc. 22nd Int. Ornithol. Congr., Durban.

Alerstam, T. (1990): Bird Migration. Cambridge (GB).

Baker, R.R. (1984): Bird Navigation — the Solution of a Mystery? London.

Baker, R.R. (1989): Human Navigation and Magnetoreception. Manchester.

Balda, R.P. & Wiltschko, W. (1991): Caching and recovery in Scrub Jays: transfer of sun-compass directions from shaded to sunny areas. Condor 93: 1020–1023.

Beck, W. & Wiltschko, W. (1988): Magnetic factors control the migratory direction of Pied Flycatchers (Ficedula hypoleuca Pallas). In: Ouellet, H. (Ed.): Acta XIX Congr. Int. Ornithol. Vol. II: 1955–1962. Ottawa.

Bellrose, F.C. (1972): Possible steps in the evolutionary development of bird navigation. In: Galler, S.R., Schmidt-Koenig, K., Jacobs, G.J., Belleville, R.E. (Eds.): Animal Orientation and Navigation: NASA SP-262: 223–257. Washington, D.C.

Berthold, P. (1988a): The control of migration in European Warblers. In: Ouellet, H. (Ed.): Acta XIX Congr. Int. Ornithol.: 215–249. Ottawa.

Berthold, P. (1988b): The biology of the genusSylvia — a model and a challenge for Afro-European cooperation. Tauraco 1: 3–28.

Berthold, P. (1990): Vogelzug. Eine kurze, aktuelle Gesamtübersicht. Darmstadt.

Berthold, P., Mohr, G. & Querner, U. (1990): Steuerung und potentielle Evolutionsgeschwindigkeit des obligaten Teilzieherverhaltens: Ergebnisse eines Zweiweg-Selektionsexperiments mit der Mönchsgrasmücke (Sylvia atricapilla). J. Ornithol. 131: 33–45.

Bovet, J., Dolivo, M., George, C. & Gogniat, A. (1988): Homing behavior of wood mice (Apodemus) in a geomagnetic anomaly. Z. Säugetierkd. 53: 333–340.

Braemer, W. (1959): Versuche zu der im Richtungsgehen der Fische enthaltenen Zeitschätzung. Verh. Dtsch. Zool. Ges. 1959: 276–288.

Curry-Lindahl, K. (1982): Das große Buch vom Vogelzug. Berlin.

DeRosa, C.T. & Taylor, D.H. (1982): A comparison of compass orientation mechanisms in three turtles (Trionyx spinifer, Chrysemys picta andTerrapene carolina). Copeia 1982: 394–399.

Drost, J. (1961): The Migration of Birds. London, Melbourne.

Dyer, F.C. & Dickinson, J.A. (1994): Development of sun compensation by honeybees: How partially experienced bees estimate the sun's course. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91: 4471–4474.

Emlen, S.T. (1967): Migratory orientation in the Indigo Bunting,Passerina cyanea. Part II: Mechanisms of celestial orientation. Auk 84: 463–489.

Emlen, S.T. (1970): Celestial rotation: its importance in the development of migratory orientation. Science 170: 1198–1201.

Ferguson, D.E. (1963): Orientation in three species of Anuran amphibians. Erg. Biol. 26: 128–134.

Ferguson, D.E. (1967): Sun compass orientation in Anurans. In: Storm, R.M. (Ed.): Animal Orientation and Navigation: 21–32. Corvallis, Oregon.

Fluharty, S.L., Taylor, D.H. & Barrett, G.W. (1976): Sun-compass orientation in the Meadow Vole,Microtus pennsylvanicus. J. Mamm. 57: 1–9.

Goodyear, C. & Ferguson, D.E. (1969): Sun-compass orientation in the Mosquitofish,Gambusia affinis. Anim. Behav. 17: 636–640.

Graue, L.C. (1963): The effect of phase shifts in the day-night cycle on pigeon homing at distances of less than one mile. Ohio J. Science 63: 214–217.

Griffin, D.R. (1952): Bird navigation. Biol. Rev. Cambridge Phil. Soc. 27: 359–400.

Griffin, D.R. (1955): Bird navigation. In: Wolfson, A. (Ed.): Recent Studies in Avian Biology: 154–197. Urbana, III.

Groot, C. (1965): On the orientation of young Sockeye Salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) during their seaward migration out of lakes. Behaviour, Suppl. 14.

Hartmann, G. & Wehner, R. (1995): The ant's path integration system: a neural architecture. Biol. Cybern. 73: 483–497.

Hasler, A., Horrall, R.M., Wisby, W.J. & Braemer, W. (1958): Sun orientation and homing in fishes. Limnol. Oceanogr. 3: 353–361.

Heinroth, O. & Heinroth, K. (1941): Das Heimfinde-Vermögen der Brieftauben. J. Ornithol. 89: 213–256.

Heinzel, H., Fitter, R. & Parslow, J. (1972): Pareys Vogelbuch. Hamburg, Berlin.

Helbig, A.J., Berthold, P., Mohr, G. & Querner, U. (1994): Inheritance of a novel migratory direction in Central European Blackcaps. Naturwissenschaften 81: 184–186.

Kalmijn, A.J. (1978): Electric and magnetic sensory world of sharks, skates and rays. In: Hodgson, F.S., Mathewson, R.F. (Eds.): Sensory Biology of Sharks, Skates and Rays: 507–528. Arlington, Va.

Keeton, W.T. (1970): Do pigeons determine latitudinal displacement from the sun's altitude? Nature 227: 626–627.

Keeton, W.T. (1974): The orientational and navigational basis of homing in birds. Adv. Study. Behav. 5: 47–132.

Kramer, G. (1950): Weitere Analyse der Faktoren, welche die Zugaktivität des gekäfigten Vogels orientieren. Naturwissenschaften 37: 377–378.

Kramer, G. (1953): Wird die Sonnenhöhe bei der Heimfindeorientierung verwertet? J. Ornithol. 94: 201–219.

Kramer, G. (1959): Recent experiments on bird orientation. Ibis 101: 399–416.

Leach, I.H. (1981): Wintering Blackcaps in Britain and Ireland. Bird Study 28: 5–14.

Light, P., Salmon, M. & Lohmann, K.J. (1993): Geomagnetic orientation of Loggerhead Sea Turtles: evidence for an inclination compass. J. Exp. Biol. 182: 1–10.

Löhrl, H. (1959): Zur Frage des Zeitpunkts einer Prägung auf die Heimatregion beim Halsbandschnäpper (Ficedula albicollis). J. Ornithol. 100: 132–140.

Marhold, S., Wiltschko, W. & Burda, H. (1997): A magnetic polarity compass for direction finding in a subterranean mammal. Naturwissenschaften 84: 421–423.

Matthews, G.V.T. (1953): Sun navigation in homing pigeons. J. Exp. Biol. 30: 243–267.

Miles, S.G. (1968): Laboratory experiments on the orientation of the adult American Eel,Anguilla rostrata. J. Fish Res. BD. Canada 25: 2143–2155.

Moreau, R. E. (1972): The Palaearctic-African Bird Migration System. London.

Munro, U. & Wiltschko, R. (1993): Clock-shift experiments with migratory Yellow-faced Honeyeaters,Lichenostomus chrysops (Meliphagidae), an Australian day migrating bird. J. Exp. Biol. 181: 223–244.

Murphy, R.G. (1989): The development of magnetic compass orientation in children. In: Orientation and Navigation — Birds, Humans and other Animals. Proc. Int. Conf. Royal Inst. Navig., paper 26. Cardiff.

Murray, R.W. (1962): The response of the ampullae of Lorenzini of elasmobranch to electrical stimulation. J. Exp. Biol. 39: 119–128.

Pennycuick, C.J. (1960): The physical basis of astronavigation in birds: theoretical considerations. J. Exp. Biol. 37: 573–593.

Phillips, J.B. (1986): Two magnetic pathways in a migratory salamander. Science 233: 765–767.

Phillips, J.B. & Borland, S.C. (1992): Behavioral evidence for use of a light-dependent magnetoreception mechanism by a vertebrate. Nature 359: 142–144.

Quinn, T.P. & Brannon, E.L. (1982): The use of celestial and magnetic cues by orienting Sockeye Salmon smolts. J. Comp. Physiol. A 147: 547–552.

Rodda, G.H. (1984): The orientation and navigation of juvenile alligators: evidence of magnetic sensitivity. J. Comp. Physiol. A 154: 649–658.

Schmidt-Koenig, K. (1979): Avian Orientation and Navigation. London.

Schüz, E., Berthold, P., Gwinner, E. & Oelke, H. (1971): Grundriß der Vogelzugskunde. Berlin.

Sinsch, U. (1990): The orientation behavior of three toad species (genusBufo) displaced from the breeding site. Fortschr. Zool. 38: 75–83.

Sokolov, L.V., Bolshakov, K.V., Vinogradova, N.V., Dolnik, T.V., Lyuleeva, D.S., Payevsky, V.A., Shumakov, M.E. & Yablonkevich, M.L. (1984): (Versuche zur Fähigkeit der Prägung und den zukünftigen Brutort zu finden bei jungen Buchfinken. — auf Russisch). Zool. J. (Moskau) 43: 1671–1681.

Starck, D. (1978): Vergleichende Anatomie der Wirbeltiere auf evolutionsbiologischer Grundlage. Band 1: Theoretische Grundlagen, Stammesgeschichte und Systematik unter Berücksichtigung der niederen Chordata. Berlin.

Sumner, E.L. & Cobb, J.L. (1928): Further experiments in removing birds from places of banding. Condor 30: 317–319.

Viguier, C. (1882): Le sens de l'orientation et ses organes chez les animaux et chez l'homme. Rev. Phil. France Etranger 14: 1–36.

Wallraff, H.G. (1974): Das Navigationssystem der Vögel. Schriftenreihe „Kybernetik“, München, Wien.

Warburton, K. (1973): Solar orientation in the snailNerita plicata (Prosobranchia: Neritacea) on a beach near Watamu, Kenya. Marine Biology 23: 93–100.

Wehner, R. (1982): Himmelsnavigation bei Insekten. Zürich.

Wehner, R. & Müller, M. (1993): How do ants acquire their celestial ephemeris function? Naturwissenschaften 80: 331–333.

Weindler, P., Beck, W., Liepa, V. & Wiltschko, W. (1995): Development of migratory orientation in Pied Flycatchers in different magnetic inclinations. Anim. Behav. 49: 227–234.

Weindler, P., Wiltschko, R. & Wiltschko, W. (1996): Magnetic information affects the stellar orientation of young bird migrants. Nature 383: 158–160.

Weindler, P., Baumetz, M. & Wiltschko, W. (1997): The direction of celestial rotation influences the development of stellar orientation in young Garden Warblers. J. Exp. Biol. 200: 2107–2113.

Weindler, P., Böhme, F., Liepa, V. & Wiltschko, W. (1998): The role of daytime cues in the development of magnetic orientation in a night-migrating bird. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 42: 289–294.

Williams, T.C. & Webb, T. (1996): Neotropical bird migration during the ice ages: orientation and ecology. Auk 113: 105–118.

Wiltschko, R. (1981): Die Sonnenorientierung der Vögel. II. Entwicklung des Sonnenkompaß und sein Stellenwert im Orientierungssystem. J. Ornithol. 122: 1–22.

Wiltschko, R. (1992): Das Verhalten verfrachteter Vögel. Vogelwarte 36: 249–310.

Wiltschko, R. & Wiltschko, W. (1978): Evidence for the use of magnetic outward-journey information in homing pigeons. Naturwissenschaften 65: 112.

Wiltschko, R. & Wiltschko, W. (1981): The development of sun compass orientation in young homing pigeons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 9: 135–141.

Wiltschko, R. & Wiltschko, W. (1990): Zur Entwicklung der Sonnenkompaßorientierung bei jungen Brieftauben. J. Ornithol. 131: 1–19.

Wiltschko, R. & Wiltschko, W. (1995): Magnetic Orientation in Animals. Berlin.

Wiltschko, R. & Wiltschko, W. (1998): Pigeon homing: Effect of various wavelengths of light during displacement. Naturwissenschaften 85: 164–167.

Wiltschko, R., Haugh, C., Walker, M. & Wiltschko, W. (1998): Pigeon homing: sun compass use in the southern hemisphere. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 43: 297–300.

Wiltschko, R., Munro, U., Ford, H. & Wiltschko, W. (1999): After-effects of exposure to conflicting celestial and magnetic cues at sunset in migratory Silvereyes,Zosterops lateralis. J. Avian Biol. 30: 56–62.

Wiltschko, W. & Balda, R.P. (1989): Sun compass orientation in seed-caching Scrub Jays (Aphelocoma coerulescens). J. Comp. Physiol. 164: 717–721.

Wiltschko, W. & Gwinner, E. (1974): Evidence for an innate magnetic compass in Garden Warblers. Naturwissenschaften 61: 406.

Wiltschko, W. & Wiltschko, R. (1976): Die Bedeutung des Magnetkompasses für die Orientierung der Vögel. J. Ornithol. 117: 362–387.

Wiltschko, W. & Wiltschko, R. (1981): Disorientation of inexperienced young pigeons after transportation in total darkness. Nature 291: 433–435.

Wiltschko, W. & Wiltschko, R. (1982): The role of outward journey information in the orientation of homing pigeons. In: Papi, F. & Wallraff, H.G. (Eds.): Avian Navigation: 239–252. Berlin.

Wiltschko, W. & Wiltschko, R. (1992): Migratory orientation: Magnetic compass orientation of Garden Warblers (Sylvia borin) after a simulated crossing of the magnetic equator. Ethology 91: 70–74.

Wiltschko, W. & Wiltschko, R. (1998): The navigation system of birds and its development. In: Balda, R.P., Pepperberg, I.M. & Kamil, A.C. (Eds.): Animal Cognition in Nature: 155–199. London.

Wiltschko, W. & Wiltschko, R. (1999): The effect of yellow and blue light on magnetic compass orientation in European Robins. J. Comp. Physiol. A 184: 295–299.

Wiltschko, W., Wiltschko, R., Keeton, W.T. & Madden, R. (1983): Growing up in an altered magnetic field affects the initial orientation of young homing pigeons. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 12: 135–142.

Wiltschko, W., Beason, R. & Wiltschko, R. (1991): Concluding remarks to the symposium ‘Sensory Basis of Orientation’. In: Williamsson, M. (Ed.): Acta XX Int. Ornithol. Congr. Christchurch 1990: 1845–1850. Christchurch, New Zealand.

Wiltschko, W., Munro, U., Ford, H. & Wiltschko, R. (1993): Red light disrupts magnetic orientation of migratory birds. Nature 364: 525–527.

Wiltschko, W., Munro, U. & Wiltschko, R. (1997): Magnetoreception in migratory birds: Light-mediated and magnetite-mediated processes? In: Orientation and Navigation — Birds, Humans and other Animals. Proc. Conf. Royal Inst. Navig., paper Nr. 1. Oxford.

Wiltschko, W., Balda, R.P., Jahnel, M. & Wiltschko, R. (1999): Sun compass orientation in seed-caching corvids: its role in spatial memory. Animal Cognition 2, im Druck.

Winn, H.E., Salmon, M. & Roberts, N. (1964): Suncompass orientation by parrot fishes. Z. Tierpsychol. 21: 798–812.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiltschko, R., Wiltschko, W. Das Orientierungssystem der Vögel IV. Evolution. J Ornithol 140, 393–417 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01650985

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01650985