Summary

-

1.

Scout ants of Camponotus socius set chemical “sign posts” (hindgut material) around newly discovered food sources. They lay a hindgut trail from the food source to the nest, however the hindgut material does not have a recruitment effect on nestmates.

-

2.

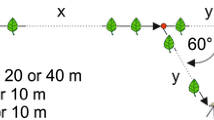

Inside the nest the recruiting ant performs a “waggle” motor display when facing nestmates head on. The vibrations with the head and thorax last 0.5–1.5 seconds (6–12 strokes in a second) (Fig. 5). Nestmates are alerted by this behavior and subsequently follow the recruiting leader ant to the food source. Up to approximately 30 ants can be stimulated successively during one recruitment performance inside the nest.

-

3.

Mass foraging is organized by the behavioral activity of individual recruiting ants.

-

4.

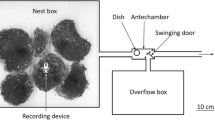

By closing the abdominal tips of recruiting ants with collophonium wax it was possible to separate the “waggle” display from the chemical signals. Thereby it could be shown that only those ants which were stimulated by a recruiting ant would follow an artificial hindgut trail.

-

5.

A leader ant is important to keep the recruited followers excited. It was possible to replace the leader ant by a microsyringe which discharged a mixture of poison gland secretion and hindgut material. Hindgut material seems to serve as long lasting orientation signals whereas poison gland content or formic acid respectively keeps the followers excited.

-

6.

Essentially the same behavioral patterns are involved during recruitment to new nest sites. The main differences are that the motor display is more a “jerking” movement (Fig. 11), furthermore males are also recruited and do respond to the signals and finally that non-responding nestmates are carried to the target area.

Zusammenfassung

-

1.

Wenn Kundschafter von Camponotus socius eine neue Futterquelle entdeckt haben, markieren sie diese und den Weg von der Futterquelle zum Nest mit Rektalblaseninhalt. Die Enddarmspur allein hat jedoch keinen stimulierenden Effekt auf Nestgenossen.

-

2.

Im Nest zeigt die werbende Kundschafterin ein spezifisches „Wackel“-Verhalten, wenn sie Nestgenossen begegnet: Sie bewegt den Kopf und Thorax 6–12 mal in der Sekunde etwa 0,5–1,5 Sekunden lang seitwärts hin und her (Fig. 5). Nestgenossen werden dadurch stimuliert und folgen schließlich der führenden Kundschafterin zur Futterquelle. Bis zu etwa 30 Arbeiterinnen können so bei einer Werbung im Nest geworben werden.

-

3.

Die Futtersammeiaktivität wird durch die Aktivität des Werbeverhaltens einzelner Arbeiterinnen reguliert.

-

4.

Indem die Gasterspitze mit Kollophonium-Wachs verschlossen wurde, konnte das „Wackel“-Verhalten von den chemischen Signalen getrennt werden. So konnte gezeigt werden, daß nur solche Ameisen einer künstlichen Enddarmspur folgen, die vorher durch das „Wackel“-Verhalten stimuliert wurden.

-

5.

Auch auf dem Weg zur Futterquelle ist die führende Kundschafterin wichtig, um die folgenden Neulinge bei „der Stange zu halten“. Die Führer-Ameise konnte jedoch durch eine Mikrospritze ersetzt werden, durch die ein Gemisch von Rektalblaseninhalt und Giftdrüsensubstanz abgegeben wurde. Weitere Versuche zeigten, daß Spuren von Rektalblaseninhalt sehr beständige chemische Orientierungssignale darstellen, während Giftdrüseninhalt bzw. Ameisensäure als sehr kurzlebiges Werbesignal wirkt.

-

6.

Beim Neulinge-Werben zu neuen Nestplätzen sind im wesentlichen die gleichen Werbesignale beteiligt. Das Verhaltensmuster im Nest ist jedoch keine „Wackelbewegung“, sondern eine zuckende Vor-zurück-Bewegung (Fig. 11); außerdem werden auch Männchen geworben und schließlich werden solche Nestgenossen, die nicht auf die Werbesignale reagieren, zum neuen Nestplatz getragen.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Blum, M. S.: The chemical basis of insect sociality. In: Beroza, M. (ed.), Chemical controlling insect behavior p. 61–94. New York and London: Academic Press 1970.

—, Wilson, E. O.: The anatomical source of the trail pheromones in Formicine ants. Psyche (Cambridge) 71, 28–31 (1964).

Carthy, J. D.: Odour trails of Acanthomyops fuliginosus. Nature, (Land.) 166, 154 (1950).

Creighton, W. S.: The ants of North America. Bull. Mus. comp. Zool. Harv. 104, 1–585 (1950).

Fletcher, D. J. C., Brand, J. M.: Source of the trail pheromone and method of trail laying in the ant Crematogaster peringueyi. J. Insect Physiol. 14, 783 to 788 (1968).

Gabba, A., Pavan, M.: Researches on trail and alarm substances in ants. In: Johnston, J. W., Jr., D. G. Moulton, and A. Turk (eds.), Communication by chemical signals p. 161–195. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts 1970.

Hangartner, W., Bernstein, S.: Über die Geruchspur von Lasius fuliginosus zwischen Nest und Futterquelle. Experientia (Basel) 20, 392–393 (1964).

Hingston, R. W. G.: Instinct and intelligence, 296 p. New York: Macmillian & Co. 1929.

Leuthold, R. H.: A tibial gland scent-trail and trail-laying behavior in the ant Crematogaster ashmeadi Mayr. Psyche (Cambridge) 75, 233–248 (1968).

—: Recruitment to food in the ant Crematogaster ashmeadi. Psyche (Cambridge) 75, 334–350 (1968).

Maschwitz, U.: Gefahrenalarmstoffe und Gefahrenalarmierung bei sozialen Hymenopteren. Z. vergl. Physiol. 47, 596–655 (1964).

Möglich, M.: Nestumzugs- und Trageverhalten bei Ameisen. Staatsexamensarbeit an der Universität Frankfurt, 1971.

Szlep-Fessel, R.: The regulatory mechanism in mass foraging and the recruitment of soldiers in Pheidole. Insectes Sociaux (in press).

Szlep, R., Jacobi, T.: The mechanism of recruitment to mass foraging in colonies of Monomorium venustum Smith, M. subopacum ssp. phoenicum Em., Tapinoma israelis For. and T. simothi v. phoenicium Em. Insectes Sociaux 14, 25–40 (1967).

Wilson, E. O.: Communication by tandem running in the ant genus Cardiocondyla. Psyche (Cambridge) 66, 29–34 (1959).

—: Source and possible nature of the odor trail of fire ants. Science 129, 643–644 (1959).

—: Chemical communication among workers of the fire ant Solenopsis saevissima (Fr. Smith). 1. The organization of mass-foraging. 2. An information analysis of the odour trail. 3. The experimental induction of social responses. Anim. Behav. 10, 134–164 (1962).

—: Trail sharing in ants. Psyche 72, 2–7 (1965).

—: The insect societies 548 p. Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Press 1971.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Dedicated to Prof. Dr. K. v. Frisch.

I wish to thank Prof. E. O. Wilson for critically reading this manuscript. I am grateful to Miss Kathy Horton for her assistance and to my wife Turid for her collaboration and for providing the illustrations. This work was supported by a grant of Max Kade Foundation and National Science Foundation No. GB-7734 (sponsor E. O. Wilson).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hölldobler, B. Recruitment behavior in Camponotus socius (Hym. Formicidae). Z. vergl. Physiologie 75, 123–142 (1971). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00335259

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00335259