Abstract

This volume was inspired by the observation that over the past 20 years, the educational system and public administration in general have changed enormously due to ideological, political and structural transformation. In practice, the mode of operation in educational organisations is characterised by a complex interplay between political and administrative objectives, negotiations and promotion of various perspectives, cultural features, professional sights and aims to adapt to external and internal pressures and influences. This has affected educational leadership that should also be seen from a complex perspective that includes relationships and active social interaction in various networks. However, there have been very few publications of the specifics of leadership in educational contexts with a wide-ranging perspective for the radically evolving operational environments and written by researchers in educational leadership and governance. Therefore, this volume has presented a joint effort for positioning, conceptualising and describing the nature and future of Finnish educational leadership for both the international and Finnish readers.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

This volume was inspired by the observation that over the past 20 years, the educational system and public administration in general have changed enormously due to ideological, political and structural transformation. In practice, the mode of operation in educational organisations is characterised by a complex interplay between political and administrative objectives, negotiations and promotion of various perspectives, cultural features, professional sights and aims to adapt to external and internal pressures and influences (Pont, 2021). This has affected educational leadership that should also be seen from a complex perspective that includes relationships and active social interaction in various networks (e.g. Marion & Uhl-Bien, 2007). However, there have been very few publications of the specifics of leadership in educational contexts with a wide-ranging perspective for the radically evolving operational environments and written by researchers in educational leadership and governance. Therefore, this volume has presented a joint effort for positioning, conceptualising and describing the nature and future of Finnish educational leadership for both the international and Finnish readers.

Our main purpose has been to provide a comprehensive overview and in-depth coverage of contemporary aspects of leadership in the field of education. Furthermore, we have congregated scholars to critically explore and discuss leadership in education in the Finnish education system in relation to international discourses around the topic. This volume strengthens the perspective of leadership in Finnish educational research by positioning leadership in education from the perspective of educational policy and governance. In addition, this volume has examined the key changes, strengths and challenges of the conceptualisation and practice of educational leadership – not forgetting the international research and theorising of the phenomenon linked to the findings and further implications.

Scholars contributing to this volume have discussed the nature of the Finnish approach to educational leadership in theory and in practice as well as investigated the national characteristics and composition of leadership, policy and governance. The chapters with their linkages to the international discourse around leadership in education provide a reflection surface and an opportunity for readers to increase their understanding about existing variation in transnational contexts in terms of the development and position(ing) of leadership within educational policy and governance.

Elements of the three dimensions – macro and policy, local and organisational and a micro dimension – tie together investigations reported in the chapters. In turn, the dimensions of leadership are connected to the theoretical and empirical perspectives of leadership in education forming the basis of this volume, that is, the contexts, conceptual approaches, school community and collaboration, and leadership profession. First, the macro and policy dimensions exist at the international and especially national policy levels that have been investigated especially in the chapters in the first two sections. The authors of these sections have considered leadership in educational contexts in a wider framework both internationally and within Finland and with various conceptual approaches by positioning and defining educational leadership in relation to both the educational policy and governance in Finland and international theoretical education theories. Second, the local and organisational dimensions are presented at the municipal and school levels and have been reflected mainly in the fourth section of this volume that focused on school communities and collaboration. Third, the micro dimension at the individual level has been investigated especially in the third section of this volume by considering educational leadership and the newly demanded competencies and practices.

The Macro and Policy Dimensions of Context and Conceptual Approaches

The development of the educational system in Finland is closely linked to the development of society and vice versa; society has changed as the level of education within the population has increased (Sahlberg, 2014; Jantunen et al., 2022). The educational policy and administration can be described as fluctuating from highly autocratic and hierarchical government via a decentralised period into a widely delegated form of governance, and then reverting somewhat towards centralisation (e.g. Moos, 2009). This fluctuation can be called ‘the pendulum effect’, and it is in connection with the overall development of Finnish society. It seems that there has been and still prevails an unstable and unsystematic balance between the autonomy of the Finnish educational system and the direction by the state. This consistent off-balance connected with the evolving operational environment has created a role for the research-based experimental educational policy which is continuously increasing. The Finnish educational system has been described as a national experimental laboratory with a lot of diversity lurking below the surface, which the autonomy of the Finnish education policy and governance allows (Chap. 2). For example, the mindset of developing and testing of new ideas can emerge through research-based experiments for the professional development of educational leadership and applying service design thinking in educational leaders’ problem-solving (Chaps. 4 and 5).

As in Western countries, and especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, also in Finland, the educational policy and system have been influenced by global administrative trends, paradigms and global organisations. The OECD and EU Commission are organisations that have played in the global field of educational politics and shaped national educational policies and developed alternative methods to influence the thinking and regulation of education in member states (Moos, 2009). The trend towards neoliberal and market politics and new public management ideology has emphasised daycare centres, schools and educational systems that are characterised by freedom, autonomy, competition, accountability and strong leadership (Moos, 2009; Pashiardis & Brauckmann, 2019). Schools are viewed as self-governing organisations, and consequently, this has broadened the range of school leaders’ tasks and responsibilities and set school leaders as strategic actors and performance-focused managers. The Finnish policy around the enhancement-led evaluation of educational matters is a milder form though, as educational leaders have the possibility to experiment and develop without being punished with economic consequences. Chapter 3 has focused on positioning the Finnish principalship including an international perspective which has provided an opportunity to compare principalship in one’s own national setting with that of Finland.

In the twenty-first century, the whole public sector, including education, has undergone enormous changes. A so-called governance wave has affected the decision-making structures both vertically and horizontally and has increased the voice of various stakeholders at the local level (Christensen, 2012). The ideology of governance emphasises networks, collaboration and participation, and in education, school-to-school networks and partnerships are understood to be powerful means for achieving knowledge creation and sharing and solving complex challenges (Crosby et al., 2017). As stressed in the chapters of this volume, school leaders are the key actors in developing and implementing collaborative, participative and network-based actions at the community level (e.g. Ainskow, 2016).

The Local and Organisational Dimensions of School Communities and Collaboration

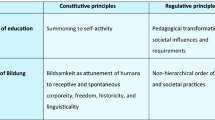

Simultaneously with the global and national development and development of new ideologies and changes at all levels of the education system, there has been a discourse about how to define educational leadership in the Finnish context. For example, if one wants to improve a school according to a Learning Outcomes Discourse, the focus is on the correct and effective enactment of goals set at the national level emphasising national and transnational tests. However, in a Democratic Bildung Discourse, the aim is to empower professionals and students to learn as much as possible and develop non-affirmative, critical and creative interpretations and negotiating competencies (Moos et al., 2020). The Finnish educational leadership discourse follows the latter which means a culture of trust in the professionals of schools without national accountability measures. However, autonomy and responsibility in the dynamic and complex governance system challenge educational leaders, their ethical leadership and competencies constantly. Thus, there is a genuine need to develop competencies and education in educational leadership, so that it can better help leaders to cope with the consistent challenges and continuous changes (Hanhimäki & Risku, 2021). The culture of trust is visible in how the multilevel educational leadership governance is structured.

Schools and other educational communities are in constant interaction with their local environments, and local municipal ecosystems and educational leaders are the foremost networkers and collaborators operating in the context of the whole local governance. This collaboration has been investigated especially in the fourth section of this volume. Consequently, the ideal of collaboration and sharing responsibilities forms a backdrop for the understanding of leadership in education (e.g. Eisenschmidt et al., 2021; Lahtero et al., 2019). Furthermore, collaboration and distribution of responsibilities are central and depending on the aim made of various compositions of people working in the public sector at the municipal level. These features have been included as one means for service provision in legislation that regulates education, pupil and youth welfare and healthcare (Basic Education Act 1998/628; Healthcare Act 1326/2010; Pupil and Student Welfare Act 2013/1287). Therefore, the ethos of collaboration has been embedded in the public sector through introduction of joint effort and collaborative practices that form the prerequisites for providing the services (Chap. 15). This is a phenomenon that is identifiable in the research designs and empirical findings indicating the existence of language of collaboration being one of the main methods for realising education at various levels and forums within the Finnish system (Chaps. 15, 16, and 18). These themes become visible through the leadership structures (groups, teams) and other forms of collective practices. One aspect of these is the structures providing the framework for a variety of encounters within the educational communities, and the other is related to behaviour of and interaction between the educators involved in these processes (Chaps. 16 and 17).

The Micro Dimension of Leadership Profession

The role of the educational leader is to be one of the actors co-designing and co-promoting services, well-being and collaborative networks, which, according to some views, have caused complexity and nonlinearity in educational settings. For example, Snyder (2013) has described education as a complex field, as a space of constant flux and unpredictability with no right answers, only emergent behaviours. Along with collaboration within schools, to gain goals that are composed of multiple elements (e.g. school-aged children’s well-being) actors representing several sectors within the public services are required. The studies in this volume also depict principals as leaders of collaborative practices and engines for the distribution of leadership and responsibilities. Further, principals are depicted as collaborators both within their schools and with outside school partners. Both dimensions require an understanding of the complexity of practices, regulations and actors related to the whole one is participating (Chaps. 15, 16 and 17).

Over the years, the professional development of educational leadership has changed from merely administrative leadership via a shared leadership within the schools towards an educational and pedagogical leadership ethically based on core values developed, jointly accepted and continuously processed by the members of the school community. New forms of sharing power over the educational system in the country are being developed. Those changes will be decided in open democratic processes in constantly ongoing debates, and other forms of governance will arise to meet the coming societal circumstances.

In this volume, we have illustrated the complexity and the fragmented nature of Finnish educational leaders’ work especially in the third section. The educational leaders and educational leadership are directed by regulations, rules and institutionalised, traditionalised practices as well as global leadership ideologies, values and administrative paradigms. Though, the position of the educational leader and the content of the leader’s work is constructed and institutionalised in a way that does not fully support or provide the necessary tools to work in today’s constantly changing environment and situations. The complexity and the dynamic nature of the educational leadership require skills and competencies such as ability to seek new solutions and methods for coping with the uncertainty. The COVID-19 pandemic is an example of the complexity, affecting educational leaders’ work and challenging their leadership (Ahtiainen et al., 2022).

In general, wicked problems resulting from the complex interaction among social, economic, institutional, political and social systems have increased and set demands in educational leaders’ work. Because of these internal and external unexpected interactions and their fluctuations, educational leaders are regularly pushed into ‘the edge of chaos situations’ (Morgan, 1997) where they are invited to view constantly changing situations as emergent properties and asked to abandon traditional modes of control and management and, instead, create conditions for systemic self-organisation and emerging situations. School leaders should have both problem-finding and problem-solving skills to address various challenges and unique issues (Nelson & Squires, 2017). In adaptive leadership, leaders should be able to adapt to constant change and to be able to change their actions and behaviour in response to different situations (Nelson & Squires, 2017; Bagwell, 2020). This requires professionalism and resilience and creates the need to possess new knowledge and competencies. In addition, this requires stepping out from the role of the traditional administrator or school manager into the role of the inspirer, motivator and collaborator.

Future Reflections for Developing Leadership in Educational Contexts

Based on the main ideas stemming from the findings in this volume and considerations of the past, present and future, we present the future reflections for developing leadership in educational contexts. We have gathered these reflections with the help of the main concepts of sustainability, professional agency and holistic understanding. We see these concepts as uniting signposts for the future and as ways for developing leadership in educational contexts. However, these concepts do not exist in a vacuum but in the middle of social reality. In addition, sustainability, professional agency and holistic understanding are the signposts of educational leadership which we need to strengthen and develop at different levels from macro to micro dimensions especially in relation to the guiding educational policy and ideals described in the middle of Fig. 19.1.

According to previous research results on ethical educational leadership in Finland, the main values and ethical principles are equality, caring and multi-professional collaboration (Hanhimäki & Risku, 2021). The meaning of fair leadership is remarkable in creativity and trust of the workplace (Collin et al., 2020). According to Rinne (2021), one of the explanatory factors of the Finnish educational success is sustainable political and educational leadership. Sustainability and a sustainable way of life are also mentioned in the educational policy documents, such as in the 2014 National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2022a) and in the 2018 National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2022b). In addition, school leaders should support the capacity building for sustainable school success (Conway, 2015).

In the everyday practices of the educational communities, both ethically easy and difficult dilemmas often concern the members of the educational staff, which emphasises the meaning of human resource management also in educational leadership (e.g. see Chap. 10). Previous research on sustainable leadership and work has underlined leaders’ remarkable role as promoters of an ethical organisational culture and of an ethically sustainable way to work (e.g. Pihlajasaari et al., 2013; Kira et al., 2010). Ethical and sustainable educational leadership increases the commitment of the members of educational communities and strengthens their well-being. Even if sustainability is not yet so well recognised in the everyday life of educational communities, it will be a future challenge and potential to strengthen it in educational leadership.

In the various contexts of educational leadership described in this volume, educational leaders influence, make decisions and in this way affect their own work all the time. In addition, educational leaders’ agency relates to the other members of the educational communities and wider networks. According to Eteläpelto et al. (2013, p. 61), ‘professional agency is practised when professional subjects and/or communities exert influence, make choices and take stances in ways that affect their work and/or their professional identities’. Eteläpelto et al. (2013) have further conceptualised professional agency within a subject-centred sociocultural framework: professional agency is both intertwined with professional subjects (e.g. their work-related identities including ethical commitments and motivations, professional knowledge and competencies and work history) and sociocultural conditions of the workplace (e.g. material circumstances, power relations, work cultures and discourses).

Educational leadership is still deeply framed and adjusted by institutional regulations, guidelines and administrative culture that impose the educational leader to work in a certain manner or through hierarchical means. This view neglects the complex nature of social reality, the nonlinearity and the dynamic nature of leadership and the speciality of each educational context. This contradictory setting may cause the feelings of frustration or anxiety among educational leaders. Educational leaders are operating in the arena of complex encounters, and foremost, educational leadership is a situated activity. It is constructed and evolved in a complex system of interactional, cultural and structural settings and is shaped by a range of stakeholders.

On the whole, the results of this volume indicate the variety of the tasks and roles educational leaders should hold. Traditionally, the role of the educational leader has been a rule-oriented administrator following educational policies, rules and regulations. The educational leader has been responsible for executing certain addressed administrative tasks. Today, first and foremost, the educational leader is a collaborator and an enabler operating in a context of local governance solving various wicked problems in different networks and collaborative groups. Competencies such as having a strategic eye, the ability to understand and predict the dynamic nature of the educational system and the whole of the governance system (micro- and megatrends) as well as the ability to understand cause-and-effect relationships are essential. Educational leaders are operating in an evolving and situated social systems in which multiple demands and competing interests are the norm rather than the exception. In these systems, it is remarkably important to take to account and develop a rich and holistic understanding about own and others’ views and life worlds (Aveling & Jovchelovitch, 2017).

References

Ahtiainen, R., Eisenschmidt, E., Heikonen, L., & Meristo, M. (2022). Leading schools during the COVID-19 school closures in Estonia and Finland. European Educational Research Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041221138989

Ainskow. (2016). Collaboration as a strategy for promoting equity in education: Possibilities and barriers. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(2), 159–175.

Aveling, E.-L., & Jovchelovitch, S. (2017). Partnerships as knowledge encounters: A psychosocial theory of partnerships for health and community development. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(1), 34–45.

Bagwell, J. (2020). Leading through a pandemic: Adaptive leadership and purposeful action. Open Journal in Education, 5(S1), 30–34.

Basic Education Act 1998/628. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/1998/en19980628.pdf

Christensen, T. (2012). Post-NPM and changing public governance. Meiji Journal of Political Science and Economics, 1, 1–11.

Collin, K., Lemmetty, S., & Riivari, E. (2020). Human resource development practices supporting creativity in Finnish growth organizations. International Journal of Training and Development, 24(4), 321–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijtd.12199

Conway, J. M. (2015). Sustainable leadership for sustainable school outcomes: Focusing on the capacity building of school leadership. Leading & Managing, 21(2), 29–45.

Crosby, B. C., Hart, P., & Torfing, J. (2017). Public value creation through collaborative innovation. Public Management Review, 19(5), 655–669.

Eisenschmidt, E., Ahtiainen, R., Kondratjev, B. S., & Sillavee, R. (2021). A study of Finnish and Estonian principals’ perceptions of strategies that foster teacher involvement in school development. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2021.2000033

Eteläpelto, A., Vähäsantanen, K., Hökkä, P., & Paloniemi, S. (2013). What is agency? Conceptualizing professional agency at work. Educational Research Review, 10, 45–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.05.001

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2022a). The 2014 National Core Curriculum for Basic Education. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/perusopetuksen_opetussuunnitelman_perusteet_2014.pdf

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2022b). The 2018 National Core Curriculum for Early Childhood Education. https://www.oph.fi/sites/default/files/documents/varhaiskasvatussuunnitelman_perusteet.pdf

Hanhimäki, E., & Risku, M. (2021). The cultural and social foundations of ethical educational leadership in Finland. In R. Normand, L. Moos, M. Liu, & P. Tulowitzki (Eds.), The cultural and social foundations on educational leadership (pp. 83–99). Springer.

Healthcare Act 1326/2010. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/kaannokset/2010/en20101326_20131293.pdf

Jantunen, A., Ahtiainen, R., Lahtero, T. J., & Kallioniemi, A. (2022). Finnish comprehensive school principals’ descriptions of diversity in their school communities. International Journal of Leadership in Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2117416

Kira, M., van Eijnatten, F. M., & Balkin, D. B. (2010). Crafting sustainable work: Development of personal resources. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(5), 616–632.

Lahtero, T. J., Ahtiainen, R., & Lång, N. (2019). Finnish principals: Leadership training and views on distributed leadership. Educational Research and Reviews, 14(10), 340–348.

Marion, R., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2007). Paradigmatic influence and leadership: The perspectives of complexity theory and bureaucracy theory. In J. K. Hazy, J. A. Goldstein, & B. B. Lichtenstein (Eds.), Complex systems leadership theory: New perspectives from complexity science on social and organizational effectiveness (pp. 143–162) Isce Pub.

Moos, L. (2009). Hard and soft governance: The journey from transnational agencies to school leadership. European Educational Research Journal, 8(3), 397–406.

Moos, L., Nihlfors, E., & Merok Paulsen, J. (Eds.). (2020). Re-centering the critical potential of Nordic school leadership research. Springer.

Morgan, G. (1997). Images of organization. SAGE.

Nelson, T., & Squires, V. (2017). Addressing complex challenges through adaptive leadership: A promising approach to collaborative problem solving. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(4), 111–123.

Pashiardis, P., & Brauckmann, S. (2019). New public management in education: A call for the entrepreneurial leader? Leadership and policy in schools., 18(3), 485–499.

Pihlajasaari, P., Feldt, T., Mauno, S., & Tolvanen, A. (2013). Resurssien ja toimivaltuuksien puute eettisen kuormittuneisuuden riskitekijänä kaupunkiorganisaation sosiaali- ja terveyspalveluissa [The shortage of resources and personal authority as a risk factor of ethical strain in social affairs and health services of the city organization]. Työelämän tutkimus, 11(3), 209–222.

Pont, B. (2021). A literature review of school leadership policy reforms. European Journal of Education, 55(1), 154–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12398

Pupil and Student Welfare Act 2013/1287. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2013/20131287

Rinne, R. (2021). Finland – The Late-comer that became the envy of its Nordic school competitors. In L. Moos & J. Krejsler (Eds.), What works in Nordic school policies? Mapping approaches to evidence, social technologies and transnational influences. Springer.

Sahlberg, P. (2014). Finnish lessons 2.0: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? Teachers College Press.

Snyder, S. (2013). The simple, the complicated, and the complex: Educational reform through the lens of complexity theory (OECD Education Working Papers, No. 96). OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k3txnpt1lnr-en

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Ahtiainen, R., Hanhimäki, E., Leinonen, J., Risku, M., Smeds-Nylund, AS. (2024). Challenges and Reflections for Developing Leadership in Educational Contexts. In: Ahtiainen, R., Hanhimäki, E., Leinonen, J., Risku, M., Smeds-Nylund, AS. (eds) Leadership in Educational Contexts in Finland. Educational Governance Research, vol 23. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37604-7_19

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-37604-7_19

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-37603-0

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-37604-7

eBook Packages: EducationEducation (R0)