Abstract

Background

Physicians and nurses face high levels of burnout. The role of care teams may be protective against burnout and provide a potential target for future interventions.

Objective

To explore levels of burnout among physicians and nurses and differences in burnout between physicians and nurses, to understand physician and nurse perspectives of their healthcare teams, and to explore the association of the role of care teams and burnout.

Design

A mixed methods study in two school of medicine affiliated teaching hospitals in an urban medical center in Baltimore, Maryland.

Participants

Participants included 724 physicians and 971 nurses providing direct clinical care to patients.

Main Measures and Approach

Measures included survey participant characteristics, a single-item burnout measure, and survey questions on care teams and provision of clinical care. Thematic analysis was used to analyze qualitative survey responses from physicians and nurses.

Key Results

Forty-three percent of physicians and nurses screened positive for burnout. Physicians reported more isolation at work than nurses (p<0.001), and nurses reported their care teams worked efficiently together more than physicians did (p<0.001). Team efficiency was associated with decreased likelihood of burnout (p<0.01), and isolation at work was associated with increased likelihood of burnout (p<0.001). Free-text responses revealed themes related to care teams, including emphasis on team functioning, team membership, and care coordination and follow-up. Respondents provided recommendations about optimizing care teams including creating consistent care teams, expanding interdisciplinary team members, and increasing clinical support staffing.

Conclusions

More team efficiency and less isolation at work were associated with decreased likelihood of burnout. Free-text responses emphasized viewpoints on care teams, suggesting that better understanding care teams may provide insight into physician and nurse burnout.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare clinicians, including physicians and nurses, experience high levels of burnout and stress.1 Burnout is defined as a syndrome resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed, including feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion, increased mental distance from one’s job, feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job, and reduced professional efficacy.2

Healthcare clinician burnout can have personal consequences for clinician well-being and health, as well as effects on the greater healthcare system. Physicians experience depression or anxiety, alcohol or drug abuse, and suicide at higher rates than the general population, and burnout can contribute to these.3,4,5 Burnout may also contribute to higher healthcare costs and reduced physician work effort and productivity, as well as increased nurse turnover and staffing issues.6,7,8,9 Patient care outcomes may be affected, with associations with lower patient satisfaction and lower patient care quality, and physicians with burnout having higher odds of self-reported medical errors or perceived medical errors.10,11,12

In order to prevent burnout, we must understand both individual- and systems-level factors that can contribute to burnout.13 Systems-level factors within healthcare organizations may play a larger role than even individual-level factors as potential drivers of burnout.1 One systems-level factor that may contribute to burnout is the role of care teams and teamwork.14,15,16 Care teams in healthcare work collaboratively to provide services and high-quality care to individuals, families, or their communities.17 These care teams may take different forms or compositions and include a variety of members from differing disciplines or professional backgrounds and can exist in all settings where healthcare is delivered.18,19

The use of teams and effective teamwork has previously been associated with improved patient outcomes, better management of chronic health conditions, decreased healthcare utilization, and decreased healthcare-associated infection rates.20,21,22,23,24,25 Better nursing-physician collaboration and nurse-nurse collaboration were associated with lower intention to leave their job and higher job satisfaction.26 However, less is known about the role of care teams and the impact on clinician burnout. By better understanding physician and nurse perspectives on care teams, we may find a target for future burnout interventions.

In this mixed methods study, we aim to explore the role of care teams and their relation to physician- and nurse-reported burnout at an academic medical center in Maryland. We examine levels of burnout at the two main teaching hospitals within the Johns Hopkins Health System, differences in burnout between physicians and nurses, and the association of care teams and burnout among physicians and nurses. We hypothesize that physicians and nurses who reported higher levels of team efficiency, less isolation, and a more supportive clinical environment would report lower levels of burnout. We also aim to understand physician and nurse reflections on the role of clinical care teams and their suggestions to improve care teams through qualitative survey responses.

METHODS

Survey Procedures

The Joy in Medicine Task Force was created at Johns Hopkins Medicine in 2016 to address clinician burnout and the factors that adversely affect joy in the delivery of healthcare. The Task Force membership was comprised of representatives within the organization’s six hospitals, physician practices, and nursing community and included some authors of this study. The Task Force identified specific domains that were relevant to their understanding of burnout among clinicians. Within each domain, survey items were developed and internally pilot-tested by the Task Force. An email message containing a hyperlink was sent in 2017 to all employees within the health system at 6 affiliate hospital locations. The survey site was hosted and maintained by Qualtrics. Three reminder e-mails were sent. Demographic information was obtained including age, sex, race, and ethnicity. Survey data was de-identified prior to analysis. The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board determined that secondary analyses of de-identified data were exempt from human subjects research requirements.

A single-item burnout measure was selected from the Mini-Z instrument, which has demonstrated correlation with the emotional exhaustion scale of the Maslach Burnout Inventory.27 Burnout was dichotomized: scores ≤ 2 (negative for burnout) versus ≥ 3 (positive for burnout).28 The Task Force identified the following domains to include in the survey1: delivering clinical care, including questions about clinical atmosphere and workload2; work-life integration, including questions on balancing demands of professional and personal life, health, and wellness3; joy in medicine/work satisfaction, including questions about joy and isolation at work. Quantitative questions were scored on 5-point Likert scales (strongly disagree to strongly agree, poor to optimal). Questions included: “The degree to which my care team works efficiently together,” “I feel isolated at work,” and “The clinical environment in which I work allows me to deliver outstanding clinical care.” The following prompts were included for free-text comments: “Comments on Delivering Clinical Care,” “Comments about Work-Life Integration,” and “General Comments and Suggestions about Joy in Medicine/Work Satisfaction.” Survey questions used for this study are included in the Appendix.

Study Participants

Study participants in these analyses were limited to physicians and registered nurses who provided direct patient care. Physicians were employed by the school of medicine and the nurses were employed at the two teaching hospitals in Maryland. Other health system hospital locations were excluded from analysis as they were community hospitals or not located in Maryland.

Quantitative Question Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were conducted to describe demographic characteristics of physicians and nurses. Chi-square analysis was performed to evaluate for differences between physician and nurses for burnout scores and each quantitative survey question. Binary cutpoints of the 5-point Likert scales were used for analysis of each quantitative question: “Poor/Marginal/Satisfactory” versus “Good/Optimal,” or “Strongly Disagree/Disagree/Neutral” versus “Agree/Strongly Agree.” A multilevel logistic regression model was conducted with the single-item burnout score as the outcome (dichotomized: scores ≤ 2 (negative for burnout) versus ≥ 3 (positive for burnout)) and predictors using each of the 3 quantitative survey questions. Covariates included profession (physician/nurse), gender (female/male), and age range (18–34 years old, 35–54 years old, 55–65 years old, and 65+ years old). Age ranges were utilized instead of rank as a covariate, as most nurses did not have a designated rank and not all physicians designated a rank. Missing values for respondents were excluded from analyses. Stata/MP16.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) was used for data analysis.

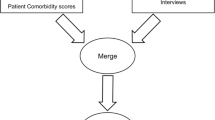

Qualitative Analysis of Free-Text Responses

A thematic analysis approach was used to analyze free-text responses. Physician and nurse free-text responses were analyzed in Microsoft Excel. Investigators (JO, ME) read all free-text comments and inductively developed a codebook. Following codebook development is line by line coding of the transcripts and iteratively updating the codebook as needed.29 Independent investigators then used the created codebook to double code each comment (physician responses: JO, ML, MS; nurse responses: ML, MS). Physician and nurse responses were analyzed separately. Threats to validity and reliability were addressed by triangulation among investigators by ensuring consensus among coders in two ways. Investigators met with principal investigator (ME) to resolve discrepancies in coding and discuss iterative changes to the codebook. Inter-rater agreement was calculated for responses. Codes were organized into themes using thematic analysis and content analysis to create conceptual themes related to care teams.30 Themes have been organized into meaningful concepts for presentation of results.

RESULTS

Demographic characteristics of respondents are included (Table 1). The response rates were 41% for the school of medicine physicians and 28% for nurses employed at both teaching hospitals. Quantitative survey responses for physicians and nurses who provided direct patient care were analyzed, with 724 physicians and 971 nurses meeting inclusion criteria.

Free-text responses for each domain were analyzed for physicians and nurses separately by job category. A total of 335 physicians (46%) and 296 nurses (30%) provided at least one response to the three free-text prompts. Inter-rater agreement was calculated to be >95% for both physician and nurse response coding.

Burnout Among Physicians and Nurses

The prevalence of burnout was 43% in physicians and 43% in nurses (Fig. 1). There was not a significant difference in burnout scores between physicians and nurses (χ2=5.8, p=NS). Questions related to clinical care were associated with burnout for physicians and nurses. In particular, care teams that worked efficiently together were significantly associated with decreased likelihood of burnout (odds ratio=0.83, p<0.01) (Table 2). More isolation at work was significantly associated with increased likelihood of burnout (OR=1.68, p<0.001). Clinical environments that allowed for delivery of outstanding clinical care were significantly associated with decreased likelihood of burnout (OR=0.76, p<0.01).

Physician and nurse burnout scores. No significant difference in burnout scores between physicians and nurses was noted (χ2= 5.8, p=215). Using a cutpoint for burnout (dichotomized: scores ≤ 2 (negative for burnout) versus ≥ 3 (positive for burnout)), 43% of physicians and nurses were positive for burnout.

Associations Between Perceptions of Care Teams and Burnout

In quantitative survey responses, 58% of nurses noted that their care team worked efficiently together, compared to only 46% of physicians, which was significantly different (χ2=19.7, p<0.001) (Fig. 2). Differences were also noted between physicians and nurses when examining quantitative responses related to isolation at work, with more physicians noting isolation at work (21%) than nurses (12%), which was significantly different (χ2=27.9, p<0.001).

Quantitative survey responses by physicians and nurses. Physician and nurse responses of binary cutpoints for the survey question (either disagree/agree, poor/good). Responses denoting “Agree” or “Good” are graphed. Chi-square tests of independence were performed between physician and nurse responses with p values noted in the graph.

In quantitative survey items, close to half of physicians and nurses did not believe that their clinical environment allowed them to deliver outstanding clinical care (Fig. 2). No differences were noted in responses to this question between physicians and nurses.

Qualitative Themes Related to Care Teams

Respondents described themes related to their care teams in free-text responses. The scope of the term “care team” was noted to vary among respondents and may be due to the healthcare setting they work in. Care teams referenced those who share the same tasks and responsibilities (such as those in the same profession), those who interact or work together in the same location, or those who contribute to the same shared goal (which may include a broader group of specialists or a multidisciplinary team who all care for the same patient).17,18,19

Three themes related to care teams emerged from thematic analysis of free-text responses1: team functioning and communication,2 team membership, and3 care coordination and follow-up. Representative quotes were selected from unique physician and nurse respondents for each theme in the text and Table 3.

Team Function and Communication

The first theme described by physicians and nurses in free-text comments was related to team functioning and communication. This theme discussed consistent care teams, staff turnover, communication and collaboration within the team, and the standard of care provided. The importance of consistent care teams and concerns about staff turnover were emphasized (Table 3). One physician discussed care team consistency affecting team function, “We don’t always have designated teams… often we are teaching folks the same thing over and over….” Frequent staff turnover of staff also was mentioned to affect team functioning.

In addition, team communication and collaboration were discussed by both physicians and nurses in free-text responses. Responses highlighted the importance of team communication and collaboration, with one nurse noted, “It creates an environment where you feel like a family instead of co-work[ers]. I look forward to come to work every day, and make sure that patient[s] gets the best out of me.” On the other hand, a physician expressed, “There is a critical gap in communication/coordination of patient care… Silo effect (surgeons/anesthesiologists/nurses) still strong….” Both physicians and nurses also commented on the importance of team members providing the same standard of patient care. One physician stated, “If I don’t do all the work needed to give this level of care… often don’t have colleagues with the same work ethic or concern for patients.”

Team Membership

The second theme described in free-text responses discussed team membership and included comments on inclusion of interdisciplinary team members and access to consultants (Table 3). Respondents discussed team membership to include interdisciplinary team members. One physician praised his team composition, “My satisfaction derives from having created a highly functioning team in a multi-disciplinary ambulatory center... who help me address the nutritional, psychosocial, and other needs simultaneously.” On the contrary, other physicians and nurses described the need for more inclusion of interdisciplinary team members, with one nurse stating, “limited to no social work on weekends, minimal OT and PT support on weekends and nights, is not sufficient….” Physicians further emphasized availability of inpatient consultants, “As a hospitalist, I rely on consultant assistance for specific cases… [one hospital] lacks consistent consultant support….”

Care Coordination and Follow-up

The third theme described in free-text responses was related to care coordination and follow-up care. This theme discussed patient communication with their care team, outpatient referrals, and coordination of follow-up care. Physicians expressed frustration about patient inability to contact clinical team members who are familiar with the patient’s health (Table 3). In particular, call center centralization was described by one physician, “[Centralization] leads to impersonal and inefficient patient phone service… a patient calling with a question talks to the call center rep, who takes a message, then to a nurse who has to call them back and then ultimately to the doctor.”

Physicians also described the length of time for outpatient referrals and care coordination and appropriate patient follow-up care. One physician stated, “Patients are left to their own devices far too much as far as scheduling imaging studies, etc. and follow up appointments. Need support for coordinating patient care…” Appropriate follow-up and care coordination was not described by nurses in these free-text responses.

Recommendations to Optimize Care Teams

Respondents further provided recommendations to improve care teams, such as creating consistent care teams, expanding interdisciplinary team members, and increasing clinical support staff (Table 4). First, creating consistent care teams was recommended, with one physician proposing, “We need smaller integrated teams that include front office, back office and clinicians all working together. Continuity, collaboration, and the development of long-term relationships would promote better patient care and would improve a sense of teamwork.” Physicians and nurses also commented on the lack of personalized patient care and issues with scheduling due to centralized call centers. One physician noted, “There is too much decentralization and rigidity (e.g. there are people who do not know me scheduling patients for me...) We have gotten away from personalized care….” Patients often navigate through a call center to ultimately reach someone who is remote from patient care. These call center staff may be unfamiliar with clinic flow, resulting in suboptimal clinic schedules and use of clinician time.

Second, respondents suggested expanding interdisciplinary team members that comprise their team to provide more care coordination and education for patients. These team members could include clinical educators, interpreter services, social work, or pharmacists. One physician specified, “Management of chronic illness requires lots of education and coordination of care… lack of nurse support/clinical educator resources a minus in delivery of satisfactory clinical care.”

Finally, both physicians and nurses recommended increasing clinical support staffing. One nurse described, “we could deliver the best care where not one patient received more than the other. With short staffing issues and complicated patients, we are unable to always deliver the excellent care all nurses want to deliver!”

DISCUSSION

This study describes high levels of burnout in physicians in an academic medical center in Maryland and demonstrates that more team efficiency and less isolation at work are associated with decreased likelihood of burnout. Furthermore, free-text responses from physicians and nurses highlight the important role of care teams and include recommendations how to improve care teams. The associations of team efficiency and isolation at work with burnout seen in this study, in conjunction with responses related to perspectives on care teams, may help provide a better understanding of drivers of burnout among physicians and nurses.

The high levels of burnout reported in our study among nurses and physicians are similar to reports in other studies.31,32,33,34 However, this survey was administered during 2017, and as a result, does not reflect high levels of burnout reported for healthcare professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic, including in a survey at this institution in 2020.35,36,37,38

Our study demonstrated that physicians and nurses who reported less team efficiency had higher likelihood of burnout. A previous study has similarly shown that physicians perceiving greater team efficiency had less burnout, and NICUs with more burnout had lower teamwork climates.28,39 Work-related factors, such as inefficient processes, excessive workloads, and lack of support from colleagues, in particular, have been associated with increased burnout.40,41,42 Another study demonstrated burnout differences in those with fully staffed teams compared to those without fully staffed teams, and burnout differences for those with turnover on their teams compared to those without turnover on their teams.43 These aspects of team functioning, including consistent care teams, and recommendations for increased clinical staffing are further highlighted in our study’s qualitative responses. Being part of an ineffective or understaffed team may increase job demands that increase exhaustion or burnout, while being a part of a high-quality and high-functioning team may be protective. In our study, less than half of physicians and less than two-thirds of nurses had responded that their care team worked efficiently together, highlighting an area for improvement in team functioning and efficiency.

Our study also demonstrated that those with more isolation at work had higher likelihood of burnout. In a survey conducted by a private company in 2018, 25% of physicians reported feeling isolated in their professional life at least once a week, and the rate of burnout increased among those reporting feeling isolated more often in their professional life.44 During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare professionals have reported feelings of isolation, including among emergency medicine providers, with a study in the UK demonstrating that feeling isolated had been associated with emotional exhaustion, similar to our findings.38,45

A respondent’s understanding of the definition of the term “care team” in survey questions and in free-text responses may have affected their responses. Their care team could have been in the inpatient setting, for instance, a hospital team providing care on the wards, a team in the operating room performing a surgical case together, or a team in the ambulatory setting seeing a clinic patient.17,18 In the inpatient setting, consultants may be included in a broader use of the word “team,” which would include those who care for the same patient in the hospital setting or those schedulers, or in the outpatient setting, clinic staff or schedulers helping with coordination of follow-up care for an ambulatory clinic patient may also be included in the care team.

Differences in responses related to isolation at work and care team efficiency were noted between physicians and nurses. First, physicians reported more isolation at work than nurses. This increased isolation may result from varying physician schedules and working in both inpatient and outpatient settings with different groups or teams. On the other hand, nurses may work within one department or unit, and therefore may work with the same team more consistently. A prior study showed that physicians working in health center with more positions or those with poor collaboration with colleagues had more perceived isolation.46 Second, nurses more frequently answered that their care team worked efficiently together. Nurses often described their care team to include fellow nurses and staff on their unit or in their clinic, while some physicians described a broader team beyond that unit or clinic, including multidisciplinary team members or specialists sharing the same hospitalized patient or clinic patient. Lastly, in contrast to nurses, physicians described concerns about patient follow-up, including access to care, referrals to specialists, or completion of procedures and testing. Physicians often follow the same patients long-term and may feel responsible for their patient’s longer term care plan and health. They may also see adverse effects of incomplete referrals at follow-up visits. Conversely, some nurses may only see patients during one clinic or shift and may not follow the same patient more longitudinally.

The themes that emerged from this study’s free-text responses correspond with similar principles of effective teams described elsewhere and in the TeamSTEPPS course (Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety) through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.17,47,48,49 Our first theme of team functioning and communication plays a role in how effectively a team functions while working together. Team members need to be able to provide information and understand each other, while working together in a collaborative environment, with clear and consistent communication between team members. Teams that have consistent members, floor units without frequent staff turnover, or staff with the same standard of care can allow team members to mutually trust and support each other and be able to accurately and quickly communicate information or plans to each other. Our second theme of team membership highlights the principle of clear roles for each team member. For instance, in an interdisciplinary team or when working with consultants, each team member has expertise in their professional discipline with specific roles or responsibilities and a resulting team structure.50

As team efficiency and isolation at work had associations with burnout, optimizing care teams which affect both these factors may help address burnout through the recommendations provided by respondents. Future interventions can focus the creation of consistent care teams, the expansion of interdisciplinary teams, or increasing clinical staff. In many institutions, utilizing staff for call centers or phone calls who are directly part of a patient’s existing care team may be difficult to implement; however, the creation of teams among call center staff who consistently cover the same department may allow for greater familiarity with clinic flow and individual physician schedules. Expansion of interdisciplinary teams in previous interventions, such as incorporating scribes or medical assistants, has been shown to positively affect physician satisfaction.40,51,52

There were limitations to this study. First, the survey was administered during 2017, so may not reflect high levels of burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, limitations existed related to survey measures. The single-item burnout measure used in this study may only characterize high levels of emotional exhaustion and does not characterize other domains of burnout such as depersonalization or reduced personal accomplishment.27,53 The selection of survey items about team efficiency, the clinical environment, and isolation at work were selected by the Joy in Medicine Task Force. Other factors previously shown to be related to burnout such as work hours, call duties, or relationship status were not collected.31 Given anonymity of survey participants, known confounders for burnout such as department/specialty were not controlled for in data analysis, as they could be potential personal identifiers in conjunction with gender, rank, and age. The practice setting of respondents was not collected on an individual level, though many of the school of medicine physicians performed both inpatient and outpatient responsibilities and the survey included nurses from both inpatient and outpatient settings. Third, response rates are 40% for the school of medicine physicians and 28% for the two teaching hospital nurses. As a result, a survey nonresponse bias may be present, and this may limit the generalizability of this institutional study. Lastly, free-text responses were not targeted to elicit responses about care teams. Study researchers performed inductive coding, and free-text responses discussing the role of care teams featured prominently in responses. While our study demonstrates team efficiency and isolation are associated with burnout, other factors that were not examined in this study may also contribute to burnout. The free-text responses obtained from this survey also contained more negative than positive responses. This may have been due to the perceived intent of the survey, to address factors adversely affecting joy in medicine, and thus, soliciting comments related to adverse effects.

Given the high levels of burnout among physicians and nurses, understanding factors that contribute to burnout or may decrease burnout is important, including systems-level factors within the hospital or organization that may be contributing. In this study, the role of care teams has emerged as a potential protector against the effects of burnout and may provide an area of resilience for clinicians who are at high risk for burnout. Ensuring future interventions improve care team function, membership, and care coordination may provide strategies for healthcare systems to mitigate burnout among nurses and physicians.

References

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Taking Action Against Clinician Burnout: a Systems Approach to Professional Well-Being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2019. Available from: https://doi.org/10.17226/25521

World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems [Internet]. 11th ed. 2019. Available from: https://icd.who.int/

Mata DA, Ramos MA, Bansal N, Khan R, Guille C, Di Angelantonio E, et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2015;314(22):2373–83.

Ruitenburg MM, Frings-Dresen MHW, Sluiter JK. The prevalence of common mental disorders among hospital physicians and their association with self-reported work ability: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:292–8.

Agerbo E, Gunnell D, Bonde JP, Mortensen PB, Nordentoft M. Suicide and occupation: the impact of socio-economic, demographic and psychiatric differences. Psychol Med. 2007;37(8):1131–40.

Han S, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Awad KM, Dyrbye LN, Fiscus LC, et al. Estimating the attributable cost of physician burnout in the United States. Ann Int Med 2019;170(11):784–90.

Shanafelt TD, Mungo M, Schmitgen J, Storz KA, Reeves D, Hayes SN, et al. Longitudinal study evaluating the association between physician burnout and changes in professional work effort. Mayo Clin Proceed 2016;91(4):422–31.

Kelly LA, Gee PM, Butler RJ. Impact of nurse burnout on organizational and position turnover. Nursing Outlook 2021;69(1):96–102.

Haddad LM, Annamaraju P, Toney-Butler TJ. Nursing shortage. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 [cited 2020 Oct 27]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493175/

Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):475–82.

Tawfik DS, Profit J, Morgenthaler TI, Satele DV, Sinsky CA, Dyrbye LN, et al. Physician burnout, well-being, and work unit safety grades in relationship to reported medical errors. Mayo Clin Proceed 2018;93(11):1571–80.

Menon NK, Shanafelt TD, Sinsky CA, Linzer M, Carlasare L, Brady KJS, et al. Association of physician burnout with suicidal ideation and medical errors. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(12):e2028780.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2016;388(10057):2272–81.

Dai M, Willard-Grace R, Knox M, Larson SA, Magill MK, Grumbach K, et al. Team configurations, efficiency, and family physician burnout. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(3):368–77.

Bruhl EJ, MacLaughlin KL, Allen SV, Horn JL, Angstman KB, Garrison GM, et al. Association of primary care team composition and clinician burnout in a primary care practice network. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2020;4(2):135–42.

Welp A, Manser T. Integrating teamwork, clinician occupational well-being and patient safety - development of a conceptual framework based on a systematic review. BMC Health Services Res 2016;16:1–44.

Mitchell P, Wynia M, Golden R, McNellis B, Okun S, Webb CE, et al. Core principles & values of effective team-based health care. NAM Perspectives [Internet]. 2012 Oct 2 [cited 2020 Oct 27]; Available from: https://nam.edu/perspectives-2012-core-principles-values-of-effective-team-based-health-care/

Chamberlain-Salaun J, Mills J, Usher K. Terminology used to describe health care teams: an integrative review of the literature. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2013;6:65–74.

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: a New Health System for the 21st Century [Internet]. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001 [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK222274/

Chang HH, Liu YL, Lu MY, Jou ST, Yang YL, Lin DT, et al. A multidisciplinary team care approach improves outcomes in high-risk pediatric neuroblastoma patients. Oncotarget. 2016;8(3):4360–72.

Pape GA. Team-based care approach to cholesterol management in diabetes mellitus: two-year cluster randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(16):1480.

Panattoni L, Hurlimann L, Wilson C, Durbin M, Tai-Seale M. Workflow standardization of a novel team care model to improve chronic care: a quasi-experimental study. BMC health services research. 2017;17(1):286.

Reiss-Brennan B, Brunisholz KD, Dredge C, Briot P, Grazier K, Wilcox A, et al. Association of integrated team-based care with health care quality, utilization, and cost. JAMA. 2016;316(8):826–34.

Meyers DJ, Chien AT, Nguyen KH, Li Z, Singer SJ, Rosenthal MB. Association of team-based primary care with health care utilization and costs among chronically ill patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):54–61.

Profit J, Sharek PJ, Kan P, Rigdon J, Desai M, Nisbet CC, et al. Teamwork in the NICU setting and its association with health care-associated infections in very low-birth-weight infants. Am J Perinatol. 2017 Aug;34(10):1032–40.

Ma C, Shang J, Bott MJ. Linking unit collaboration and nursing leadership to nurse outcomes and quality of care. J Nurs Adm. 2015;45(9):435–42.

Rohland BM, Kruse GR, Rohrer JE. Validation of a single-item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health 2004;20(2):75–9.

Olson K, Sinsky C, Rinne ST, Long T, Vender R, Mukherjee S, et al. Cross-sectional survey of workplace stressors associated with physician burnout measured by the Mini-Z and the Maslach Burnout Inventory. Stress Health 2019;35(2):157–75.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Res Psychol 2006;3(2):77–101.

Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, Trockel M, Tutty M, Satele DV, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94(9):1681–94.

Sharp M, Burkart KM, Adelman MH, Ashton RW, Biddison LD, Bosslet GT, et al. A national survey of burnout and depression among fellows training in pulmonary and critical care medicine: a special report by the APCCMPD. Chest 2020 18;

Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, Herrin J, Wittlin NM, Yeazel M, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA 2018;320(11):1114.

PRC National Nursing Engagement Report. Utilizing the PRC Nursing Quality Assessment Inventory [Internet]. PRC; 2019 Apr. Available from: https://prccustomresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/PRC_Nursing_Engagement_Report/PRC-NurseReport-Final-031819-Secure.pdf

“Death by 1000 Cuts”: Medscape National Physician Burnout & Suicide Report 2021 [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 29]. Available from: https://www.staging.medscape.com/slideshow/2021-lifestyle-burnout-6013456

Ghahramani S, Lankarani KB, Yousefi M, Heydari K, Shahabi S, Azmand S. A systematic review and meta-analysis of burnout among healthcare workers during COVID-19. Front Psychiatry 2021;12:758849.

Van Wert MJ, Gandhi S, Gupta I, Singh A, Eid SM, Haroon Burhanullah M, et al. Healthcare worker mental health after the initial peak of the COVID-19 pandemic: a US medical center cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 6;

Kelker H, Yoder K, Musey P, Harris M, Johnson O, Sarmiento E, et al. Prospective study of emergency medicine provider wellness across ten academic and community hospitals during the initial surge of the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21(1):36.

Profit J, Sharek PJ, Amspoker AB, Kowalkowski MA, Nisbet CC, Thomas EJ, et al. Burnout in the NICU setting and its relation to safety culture. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;23(10):806–13.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–29.

Williams ES, Manwell LB, Konrad TR, Linzer M. The relationship of organizational culture, stress, satisfaction, and burnout with physician-reported error and suboptimal patient care: results from the MEMO study. Health Care Manage Rev. 2007;32(3):203–12.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–46.

Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, Wood GB, Taylor L, Schectman G, et al. The association of team-specific workload and staffing with odds of burnout among VA primary care team members. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):760–6.

Feeling isolated is a key driver of physician burnout | athenahealth [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.athenahealth.com/knowledge-hub/practice-management/disconnected-isolation-and-physician-burnout

Zhou AY, Hann M, Panagioti M, Patel M, Agius R, Van Tongeren M, et al. Cross-sectional study exploring the association between stressors and burnout in junior doctors during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United Kingdom. J Occup Health. 2022 Jan;64(1):e12311.

Mäntyselkä P, Aira M, Vehviläinen A, Kumpusalo E. Increasing size of health centres may not prevent occupational isolation. Occupational Medicine. 2010;60(6):491–3.

Katzenbach JR, Smith DK. The wisdom of teams: creating the high-performance organization. Harvard Business Review Press; 2015. 315 p.

TeamSTEPPS® | Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [Internet]. [cited 2022 Jun 5]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/index.html

Stoller JK. Building teams in health care. Chest 2021;159(6):2392–8.

Parker GM. Team players and team work: new strategies for developing successful collaboration. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA : Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass ; J. Wiley & Sons; 2008. 229 p.

DeChant PF, Acs A, Rhee KB, Boulanger TS, Snowdon JL, Tutty MA, et al. Effect of organization-directed workplace interventions on physician burnout: a systematic review. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2019;3(4):384–408.

Pozdnyakova A, Laiteerapong N, Volerman A, Feld LD, Wan W, Burnet DL, et al. Impact of medical scribes on physician and patient satisfaction in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(7):1109–15.

Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, Joos S, Fihn SD, Nelson KM, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 May;30(5):582–7.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers 5T32HL072748-18, 5T32HL072748-19, NIH F32 HL143864-01, and T32HL007534.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Monica A. Lu and Jacqueline O’Toole are co-first authors.

Michelle N. Eakin and E. Lee Daugherty Biddison are co-senior authors.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 72 kb)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lu, M.A., O’Toole, J., Shneyderman, M. et al. “Where You Feel Like a Family Instead of Co-workers”: a Mixed Methods Study on Care Teams and Burnout. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 341–350 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07756-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07756-2