Abstract

In this sociometric study, we aimed to investigate the social position of gender-referred children in a naturalistic environment. We used a peer nomination technique to examine their social position in the class and we specifically examined bullying and victimization of gender dysphoric children. A total of 28 children (14 boys and 14 girls), referred to a gender identity clinic, and their classmates (n = 495) were included (M age, 10.5 years). Results showed that the gender-referred children had a peer network of children of the opposite sex. Gender-referred boys had more nominations on peer acceptance from female classmates and less from male classmates as compared to other male classmates. Gender-referred girls were more accepted by male than by female classmates and these girls had significantly more male friends and less female friends. Male classmates rejected gender-referred boys more than other boys, whereas female classmates did not reject the gender-referred girls. For bullying and victimization, we did not find any significant differences between the gender-referred boys and their male classmates nor between the gender-referred girls and their female classmates. In sum, at elementary school age, the relationships of gender dysphoric children with opposite-sex children appeared to be better than with same-sex children. The social position of gender-referred boys was less favorable than that of gender-referred girls. However, the gender-referred children were not more often bullied than other children, despite their gender nonconforming behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Peer relations are important for children’s well-being, because problems with peers in childhood may contribute to the genesis of disorders (e.g., Hay, Payne, & Chadwick, 2004; Sourander et al., 2007). Peer relations in childhood are usually gender-segmented (Maccoby, 1998). Same-sex peers are more liked and less disliked than other-sex peers (Dijkstra, Lindenberg, & Veenstra, 2007). Most children prefer same-sex friendships and their interactions are often characterized by gender-related qualities, including patterns of sex-typed play and social interaction styles (e.g., Maccoby & Jacklin, 1987). In general, children consider same-sex friendships and play styles more acceptable than being friends with children of the other sex or having a play style of the other sex. Moreover, there is evidence that children react negatively to atypical gender behavior of other children (Carter & McCloskey, 1984; Levy, Taylor, & Gelman, 1995; Ruble et al., 2007; Signorella, Bigler, & Liben, 1993; Smetana, 1986; Stoddart & Turiel, 1985).

Children with gender identity disorder (GID) experience feelings of belonging to the other sex, a strong cross-gender identification, and a persistent discomfort with their biological sex or the gender role associated with their sex. Children with GID usually prefer playmates and toys of the opposite sex and they also have their play styles. There are a number of studies that have examined whether gender-referred children showed more cross-gender behaviors and feelings than non-referred children (e.g., Fridell, Owen-Anderson, Johnson, Bradley, & Zucker, 2006; Johnson et al., 2004; Cohen-Kettenis, Wallien, Johnson, Owen-Anderson, Bradley, & Zucker, 2006; for an overview, see Zucker & Bradley, 1995). Fridell et al. (2006) compared the preferences for playmates and play styles in gender-referred children (199 boys, 43 girls) with those of controls (96 boys, 38 girls): The gender-referred children significantly preferred other-sex playmates and cross-sex play styles. In studies of Johnson et al. (2004), using a parent questionnaire, and Wallien et al. (in press), using a semi-structured child interview, gender-referred children showed significantly more gender atypical behaviors and cross-gender feelings than the children in the control groups.

Because children with GID show extreme gender atypical behavior, it is often assumed that they have a deviant social position, poor peer relations, and are victimized by peers. Green (1976) conducted a longitudinal study involving four groups of children: Feminine boys, non-feminine boys, masculine girls, and non-masculine girls. He conducted clinical interviews with the children and used parental descriptions of the boys’ or girls’ behaviors. The feminine boys appeared to relate best to same-age girls and next best to older girls, whereas the masculine boys related best to boys of all ages. Moreover, the feminine boys were more often rejected by their peers or withdrawn than the masculine boys. Green, Williams, and Goodman (1982) reported on maternal ratings of peer group relations of the four groups. The non-feminine boys and the non-masculine girls were more likely to have good same-sex peer group relations than the feminine boys and the masculine girls. The feminine boys had poorer same-sex relations than the masculine girls.

Zucker, Bradley, and Sanikhani (1997) constructed a Peer Relations Scale from the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach, 1991) and obtained CBCL data of 275 gender-referred children and their siblings. The Peer Relation Scale consisted of three items: “Does not get along with other kids,” “Gets teased a lot,” and “Not liked by other kids” (internal consistency was .81). They showed that, according to their parents, gender-referred children (both boys and girls) had significantly poorer peer relations than their siblings, and the gender-referred boys tended to have poorer peer relations than the gender-referred girls. However, the Peer Relations Scale reported by Zucker et al. (1997) did not specify the sex of the children’s peers. Possibly, parents would report differences for the items as a function of the sex of the peers, i.e., Gets teased a lot by boys or Gets teased a lot by girls. A subsequent CBCL study by Cohen-Kettenis, Owen, Kaijser, Bradley, and Zucker (2003) on data of 358 Canadian gender-referred children and 130 Dutch gender-referred children was in line with the conclusions of Zucker et al. (1997). These studies imply that, according to their parents, children showing gender atypical behaviors function worse socially than their peers. However, parents are not always fully aware of what happens in their child’s social environment and, therefore, it is possible that parental measurements do not provide a complete or accurate picture.

In one observational study (Fridell, 2001), it was examined whether non-referred boys and girls liked to play with gender-referred boys. Fridell created age-matched experimental playgroups consisting of a gender-referred boy and two non-referred boys and two non-referred girls (age range, 3–8 years). After two play sessions, conducted a week apart, each child had to select their favorite playmate from the group. Non-referred boys and girls chose most often other non-referred children, indicating a distinct preference over the gender-referred boy.

Bates, Bentler, and Thompson (1979) used parental report to assess the number of male and female playmates of so-called gender-deviant, normal, and clinical control boys. Boys with gender problems had more female playmates than clinical control boys and less male playmates than normal and clinical control boys.

In the current study, we extended these previous methods by examining sociometric data from the naturalistic environment (the school classroom) to investigate the social position of gender-referred children. We included both boys and girls referred to our clinic because of gender dysphoria. We used a peer nomination technique to assess whether peers liked or disliked their gender atypical classmates and whether they bullied them or were victimized by them (Veenstra et al., 2007).

Victimization was studied because normative studies have shown that peer relations are important for children’s well-being and that childhood victimization has long-term negative consequences (e.g., Bond, Carlin, Thomas, Rubin, & Patton, 2001; Kumpulainen & Räsänen, 2000; Sourander et al., 2007). It has even been argued that, in children with GID, like in homosexual or bisexual people, it is related to co-morbid psychiatric disorders (Carbone, 2008; Green, 1987), probably through a mechanism involving minority stress (Meyer, 2003).

Bullying often takes place at school (Olweus, 1993) and is more frequent among boys than girls (e.g., Boulton & Underwood, 1992). Furthermore, boys are more negatively judged when showing gender atypical behaviors than are girls (Antill, Cotton, Russell, & Goodnow, 1996; Zucker & Bradley, 1995) and boys are more negative about gender norm violations than girls (Blakemore, 2003; Killen & Stangor, 2001; Zucker, Wilson-Smith, Kurita, & Stern, 1995). Gay or bisexual males in middle or late adolescence reported to have been victimized mostly by other males, whereas lesbians or bisexual females were victimized nearly equally by males and females (D’Augelli, Grossman, & Starks, 2006).

We expected that the gender-referred children would be more rejected by same-sex peers and more accepted by opposite-sex peers as compared to non-referred children. We expected that, in our study, the gender-referred boys would be more accepted by female than by male classmates, and more rejected and victimized by male than by female classmates. For gender-referred girls, we expected that they would be more accepted by male than by female classmates, but victimized by both male and female classmates (though less so than the gender-referred boys). Finally, we expected gender-referred girls to be more accepted by same-sex peers than gender-referred boys.

Method

Participants

The group of gender-referred children was solicited from a cohort of children age 7 years or older referred to the Gender Identity Clinic of the Department of Medical Psychology of the VU University Medical Center (VUmc) in Amsterdam between 2004 and 2006. The Ethical Committee of the VUmc approved the study.

Of the 44 referred children, 28 children (14 boys and 14 girls) and all their classmates participated in this study. All referred children had clear cross-gender preferences and identified with the other sex (8 of the boys and 7 of the girls had a GID diagnosis, 6 of the boys and 7 of the girls were subthreshold for GID).

Sixteen of the 44 children did not take part in the study because their parents did not give permission to contact the school (n = 4) or because the school refused to participate (n = 12). The group of non-participants consisted of 9 girls (7 with a GID diagnosis, 2 were subthreshold for GID) and 7 boys (3 with a GID diagnosis and 4 were subthreshold for GID). The mean age of the participating gender-referred children was 10.47 years (SD = 1.27; range, 8.11–12.77).

Ninety-seven percent of the classmates participated in the study. The sample yielded 523 children from 27 elementary school classes (23 regular and 4 special education): 232 girls (44.4%) and 291 boys (55.6%), with a mean age of 10.59 years (SD = 1.32). The mean class size was 19.4 children (SD = 4.4). Schools were situated in both rural and (sub-)urban areas. The percentage of children with parents with a low educational level, at maximum a certificate of secondary vocational education, was 16.9%. The percentage of children from ethnic minorities (of whom at least one parent was born outside the Netherlands) was 18.7%.

Procedure

At the first clinical session of the gender-referred child with the family, parents or caregivers received a letter in which the purpose of the study was explained. Parents were asked permission to contact the school of their child. If they gave permission, we sent a letter to the school of the child explaining the study. If the school wanted to participate, a research assistant visited the school of the gender-referred child. The consent of the controls to participate in the study was under jurisdiction of the school.

The peer-nomination data were collected during school hours, from October 2005 to March 2007. Children completed the questionnaires in the school class, under the supervision of a research assistant. Before the research assistant visited the school, the first author called the teacher to make an appointment. She asked teachers not to mention the gender dysphoric child when explaining the procedure to the children. All children (our patients included) were thus unaware of the target child. Furthermore, the name of the target child was not given to the research assistant; thus, the assistant was also unaware of the target child.

Measures

Peer Acceptance and Rejection

Children were asked to nominate their classmates on a range of behaviors. The number of nominations they could make was unlimited (they were not required to nominate anyone) and same-sex as well as other-sex nominations were allowed. The numbers of nominations children received individually from their same- and other-sex classmates with regard to “best friends” and “dislike” were used to create measures of same- and other-sex peer acceptance and peer rejection. After the numbers of received nominations had been summed, proportions were calculated to take differences in the number of respondents per class into account, yielding scores from 0 to 1 (see Veenstra et al., 2007 for more information on this dyadic peer nomination procedure).

Bullying and Victimization

The term bullying was defined to the students in the way formulated in the Olweus’ Bully/Victim questionnaire (Olweus, 1996), which emphasizes the repetitive nature of bullying and the power imbalance between the bully and the victim. Several examples covering different forms of bullying were given. It was also stated that bullying can take place on the Internet or via text messages. Moreover, an explanation of what did not constitute bullying (e.g., teasing in a friendly and playful way; fighting between children of equal strength) was also given.

The numbers of nominations children received individually from their same- and other-sex classmates with regard to different forms of bullying and victimization were used to create measures of same- and other-sex bullying and victimization. We asked “who do you bully?” and “by whom are you bullied?”, using five forms of bullying and victimization: (1) taking things; (2) hitting, kicking, or pinching; (3) throwing things; (4) calling names or laughing; (5) excluding or ignoring. A sample item was “which classmates do you bully by taking things from them?” There were no clear differences in the association of the different forms of bullying and victimization with peer status. For that reason, we combined the different forms in highly reliable scales for bullying and victimization (internal consistency: .89 and .87, respectively).

For control children, bullying towards boys correlated .50 (p < .01) with bullying towards girls. Being victimized by boys correlated .39 (p < .01) with victimization by girls. The correlation of bullying towards and being victimized by same-sex classmates was .61 (p < .01) for boys and .48 (p < .01) for girls (see also Table 2).

Prosociality

The number of nominations children received from their classmates with regard to four prosociality items was used to create a measure of prosociality. The peer nomination items were: Which classmates “… invite you to play (e.g., for a game)?”, “…share things with you (e.g., when they have something delicious)?”, “…help you when you are sad?”, and “…help you with school assignments?” The internal consistency of the scale was .82. For control children, prosociality towards boys correlated −.35 (p < .01) with prosociality towards girls.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariate analyses of variance were used to ascertain differences between nominations of the gender dysphoric children and their classmates and to examine the differences between the received nominations for each sex separately.

Results

Gender-Referred Children Versus all Other Children

In general, the overall mean rate of nominations of the gender-referred children did not differ from the mean rate of the other children on peer acceptance, peer rejection, prosociality, and bullying and victimization scale. The overall MANOVA was F(15, 507) < 1.

Gender-Referred Boys Versus Other Boys

Table 1 shows the differences in Peer acceptance, Peer rejection, Prosociality, Bullying and Victimization as a function of group (gender-referred versus control children). For boys, the overall MANOVA, F(15, 275) = 8.34, p < .001, indicated that gender-referred boys differed from the other boys in their social position. It appeared that gender-referred boys had more nominations on peer acceptance from female classmates, and less from male classmates as compared to other male classmates (see Peer acceptance scale Table 1, column 2 and 3).

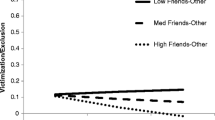

For peer rejection, male classmates nominated gender-referred boys significantly more often than other male classmates as someone they disliked, and female classmates nominated the gender-referred boys significantly less often than other male classmates as disliked. For prosociality, gender-referred boys differed from their male classmates: Gender-referred boys were more often considered helpful by female classmates than their male classmates. For bullying and victimization, we did not find any significant differences between the gender-referred boys and their male classmates.

Most gender-referred boys received at least one best friend nomination from male classmates (92.9%). However, gender-referred boys (92.9%) had more often at least one best friend among girls than their male classmates (56.3%), z(289) = 2.46, p < .05.

Of the gender-referred boys, 78.6% received at least one dislike nomination by their male classmates compared with 54.9% of their male classmates, z(289) = 1.49, ns. In contrast, 57.1% of the gender-referred boys received at least one dislike nomination of their female classmates compared to 77.3% of their male classmates, z(289) = −1.39, ns.

Gender-Referred Girls Versus Other Girls

For girls, the overall MANOVA, F(15, 216) = 4.91, p < .001, indicated that gender-referred girls differed from the other girls in their social position. Gender-referred girls were more accepted by male than by female classmates. These girls had significantly more male friends and less female friends (see Table 1, column 5 and 6). For peer rejection, we found that male classmates rejected the gender-referred girls less than they rejected other girls. However, female classmates did not reject gender-referred girls significantly more than other girls. In addition, gender-referred girls were considered more helpful by male classmates and less helpful by female classmates compared to other girls. For bullying and victimization, we did not find any significant differences between the gender-referred girls and their female classmates.

A significantly higher percentage of the gender-referred girls (92.9%) received at least one best friend nomination from their male classmates compared with their other female classmates (61%), z(230) = 2.12, p < .05. The proportion of gender-referred girls that received at least one best friend nomination from their female classmates (71.4%) differed significantly from the proportion of their female classmates that received at least one best friend nomination (95%), z(230) = −2.98, p < .01. Fifty percent of the gender-referred girls received at least one dislike nomination from their male classmates compared to 64.2% of their female classmates, z(230) = −0.77, p = .44. Of the gender-referred girls, 42.9% had at least one same-sex dislike nomination compared to 45.4% of their female classmates, z(230) = −0.13, ns.

Correlations Between Dependent Variables

Table 2 shows the correlations between study variables for gender-referred and control children. It turns out that the correlations are quite similar for gender-referred and control children, with some notable exceptions: Among control children, bullying toward boys was related to rejection by girls (r = .40), whereas it was unrelated for gender-referred children (−.04). This difference is significant, z = 2.26, p = .02. Victimization by boys was for control children related to rejection by girls (r = .35), whereas it was unrelated for gender-referred children (−.03). This difference is marginally significant, z = 1.93, p = .054. Victimization by girls was for control children related to rejection by boys (r = .35), whereas it was unrelated for gender-referred children (−.03). This difference is marginally significant, z = 1.93, p = .054.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the social position of gender dysphoric children and whether these children were bullied at school. The social position of the gender-referred children varied as a function of the sex of their classmates. Gender-referred boys were more accepted by female classmates than by male classmates and more rejected by male than by female classmates. Gender-referred girls were more accepted by male classmates than by female classmates and more rejected by female than by male classmates.

Comparing the gender-referred boys to male classmates and the referred girls to female classmates, our results were in line with Green’s studies (Green, 1976; Green et al., 1982) of maternal reports on peer-group relations of feminine boys and masculine girls. Both gender dysphoric boys and girls had peer networks of children of the opposite sex. That is, the ratings of the gender-referred children were the mirror image of the male and female classmates’ ratings. Male classmates accepted other male classmates more than the gender-referred boys, and female classmates accepted the gender-referred boys more than other male classmates. For referred girls, we found that male classmates accepted these girls more than other female classmates, whereas female classmates accepted other female classmates more than the gender-referred girls. Furthermore, the gender-referred children apparently showed more prosocial behavior towards opposite sex than same-sex peers.

We did not find that gender-referred children were more often bullied than the other children. We found, however, in agreement with normative studies (e.g., Fagot, 1977; Langlois & Downs, 1980) and the study of Green (1976), that the referred boys experienced more negative social consequences of their gender nonconforming behaviors than the referred girls. Female classmates did not reject the gender dysphoric girls, whereas gender dysphoric boys were clearly rejected by other boys. Gender-referred boys might thus experience more problems in their contact with same-sex peers, at least during the elementary school years.

Although gender-referred children were accepted by opposite-sex classmates, the gender-referred boys were more rejected by male peers than their male classmates. From some CBCL studies (Cohen-Kettenis et al., 2003; Zucker et al., 1997), it was concluded that gender-referred children generally have poor relationships. This notion should be adjusted as our study shows that it apparently only holds for same-sex relationships. Gender-referred children do appear to have other relationships than their peers (that is with other-sex peers), which are not necessarily poor. The findings of the earlier studies might be explained by a misinterpretation of the parents of their child’s relations. Because GID children have few or no same-sex friends, parents may interpret this as poor peer relations, even though the children may be satisfied with their other-sex relationships.

An explanation for the acceptance of gender dysphoric children might be that children usually stay in the same group during elementary education. This makes that the classmates of the gender dysphoric children were familiar with them for such a long time that personal experiences with the child might have overridden more general expectations, beliefs, and negative attitudes regarding gender variance (Martin, Fabes, Evans, & Wyman, 1999). Unfortunately, we do not have the information to test this explanation.

Also, most rates on homophobic bullying so far were based on self-reports of adolescents or adults. It is possible that adolescents treat gender nonconforming behavior differently than children, because in early adolescence other-sex friendships begin to emerge (Feiring, 1999; Shrum, Cheek, & Hunter, 1988) and their social networks become more mixed (Poulin & Penderson, 2007). Features that underlie attraction to same- and other-sex peers change from childhood to early adolescence (Bukowski, Sippola, & Newcomb, 2000). Likewise, features that underlie rejection and bullying might change when children transition from elementary school to high school. Retrospective reports on bullying from adults and adolescents may have reflected high school experiences rather than elementary school experiences.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this study was that we have investigated a sample of 28 gender-referred children and all their classmates. Information on gender-referred children usually stems from parent or self-reports. In our study, classmates of gender-referred children provided information on peer relations, prosociality, bullying, and victimization. It is likely that the classmates gave a more complete and accurate picture than parents or gender-referred children themselves do, especially because the classmates were unaware of the true nature of the study.

A limitation was that our sample of gender-referred children was relatively small. However, smaller samples often occur in research among referred populations having rare conditions. With our sample size, we could still detect differences between gender-referred boys and girls and their same-sex classmates at the level of 2% explained variance. Thus, our sample appeared to be large enough to find differences with a small effect size.

In sum, our study showed that, at elementary school age, the relationships of gender dysphoric children with opposite-sex children are indeed better than with same-sex children. The position of gender-referred girls seemed to be relatively better than of gender-referred boys. However, in the 27 studied school classes in the Netherlands, the gender-referred children were not more often bullied than other children, despite their gender nonconforming behavior.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist and 1991 Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Antill, J. K., Cotton, S., Russell, G., & Goodnow, J. J. (1996). Measures of children’s sex-typing in middle childhood, II. Australian Journal Psychology, 48, 35–44.

Bates, J. E., Bentler, P. M., & Thompson, S. K. (1979). Gender-deviant boys compared with normal and clinical control boys. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 7, 243–259.

Blakemore, J. E. O. (2003). Children’s beliefs about violating gender norms: Boys shouldn’t look like girls, and girls shouldn’t act like boys. Sex Roles, 48, 411–419.

Bond, L., Carlin, J. B., Thomas, L., Rubin, K., & Patton, G. (2001). Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. British Medical Journal, 323, 480–484.

Boulton, M. J., & Underwood, K. (1992). Bully/victim problems among middle school children. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 62, 73–87.

Bukowski, W. M., Sippola, L. K., & Newcomb, A. F. (2000). Variations in patterns of attraction to same- and other-sex peers during early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 36, 147–154.

Carbone, D. J. (2008). Treatment of gay men for post-traumatic stress disorder resulting form social ostracism and ridicule: Cognitive behavior therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing approaches. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37, 305–316.

Carter, D. B., & McCloskey, L. A. (1984). Peers and the maintenance of sex-typed behavior: The development of childrens’ conceptions of cross-gender behavior in their peers. Social Cognition, 2, 294–314.

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Owen, A., Kaijser, V. G., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J. (2003). Demographic characteristics, social competence, and behavior problems in children with gender identity disorder: A cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31, 41–53.

Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Wallien, M., Johnson, L. L., Owen-Anderson, A. F., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J. (2006). A parent-report gender identity questionnaire for children: A cross-national, cross-clinic comparative analysis. Clinical Child Psychology Psychiatry, 11, 397–405.

D’Augelli, A. D., Grossman, A. H., & Starks, M. T. (2006). Childhood gender, atypicality, victimization, and PTSD among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 21, 1462–1476.

Dijkstra, J. K., Lindenberg, S., & Veenstra, R. (2007). Same-gender and cross-gender peer acceptance and peer rejection and their relation to bullying and helping among preadolescents: Comparing predictions from gender-homophily and goal-framing approaches. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1377–1389.

Fagot, B. I. (1977). Consequences of moderate cross-gender behavior in preschool children. Child Development, 48, 902–907.

Feiring, C. (1999). Other-sex friendships networks and the development of romantic relationships in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 23, 495–512.

Fridell, S. R. (2001). Sex-typed behavior and peer-relations in boys with gender identity disorder. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto.

Fridell, S. R., Owen-Anderson, A., Johnson, L. L., Bradley, S. J., & Zucker, K. J. (2006). The Playmate and Play Style Preferences Structured Interview: A comparison of children with gender identity disorder and controls. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 729–737.

Green, R. (1976). One-hundred ten feminine and masculine boys: Behavioral contrasts and demographic similarities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 5, 425–446.

Green, R. (1987). The “sissy boy syndrome” and the development of homosexuality. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Green, R., Williams, K., & Goodman, M. (1982). Ninety-nine “tomboys” and “non- tomboys”: Behavioral contrast and demographic similarities. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 11, 247–266.

Hay, D. F., Payne, A., & Chadwick, A. (2004). Peer relations in childhood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 84–108.

Johnson, L. L., Bradley, S. J., Birkenfeld-Adams, A. S., Kuksis Radzins, M. A., Maing, D. M., Mitchell, J. N., et al. (2004). A parent-report Gender Identity Questionnaire for Children. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33, 105–116.

Killen, M., & Stangor, C. (2001). Children’s social reasoning about inclusion and exclusion in gender and race peer group contexts. Child Development, 72, 174–186.

Kumpulianen, K., & Räsänen, E. (2000). Children involved in bullying at elementary school age: Their psychiatric symptoms and deviance in adolescence. An epidemiological study. Child Abuse and Neglect, 24, 1567–1577.

Langlois, J. H., & Downs, A. C. (1980). Mothers, fathers, and peers as socialization agents of sex-typed play behaviors in young children. Child Development, 51, 1237–1247.

Levy, G. D., Taylor, M. G., & Gelman, S. A. (1995). Traditional and evaluative aspects of flexibility in gender roles, social conventions, moral rules, and physical laws. Child Development, 66, 515–531.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing apart, coming together. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

Maccoby, E. E., & Jacklin, C. N. (1987). Gender segregation in childhood. Advances in Child Development and Behavior, 20, 239–287.

Martin, C. L., Fabes, R. A., Evans, S. M., & Wyman, H. (1999). Social cognition on the playground: Children’s belief about playing with girls versus boys and their relations to sex segregated play. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 16, 751–771.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Oxford: Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1996). The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire [mimeograph]. Bergen, Norway: University of Bergen Research Center for Health Promotion.

Poulin, F., & Penderson, S. (2007). Developmental changes in gender composition of friendship networks in adolescent girls and boys. Developmental Psychology, 43, 1484–1496.

Ruble, D. N., Taylor, L., Cyphers, L., Greulich, F. K., Lurye, L. E., & Shrout, P. E. (2007). The role of gender constancy in early gender development. Child Development, 78, 1121–1136.

Shrum, W., Cheek, N. H., & Hunter, S. M. (1988). Friendships in school: Gender and racial homophily. Sociology of Education, 61, 227–239.

Signorella, M. L., Bigler, R. S., & Liben, L. S. (1993). Developmental differences in children’s gender schemata about others: A meta-analytic review. Developmental Review, 13, 147–183.

Smetana, J. G. (1986). Preschool children’s conceptions of sex-roles transgressions. Child Development, 57, 862–871.

Sourander, A., Jensen, P., Rönning, J. A., Helenius, N. H., Sillanmäki, L., Kumpulainen, K., et al. (2007). What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” Study. Pediatrics, 120, 397–404.

Stoddart, T., & Turiel, E. (1985). Childrens’concepts of cross-gender activities. Child Development, 56, 1241–1252.

Veenstra, R., Lindenberg, S., Zijlstra, B. J. H., De Winter, A. F., Verhulst, F. C., & Ormel, J. (2007). The dyadic nature of bullying and victimization: Testing a dual perspective theory. Child Development, 78, 1843–1854.

Wallien, M. S. C., Quilty, L. C., Steensma, T. D., Singh, D., Lambert, S. L., Leroux, A., et al. (in press). Cross-national replication of the Gender Identity Interview for Children. Journal of Personality Assessment.

Zucker, K. J., & Bradley, S. J. (1995). Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. New York: Guilford Press.

Zucker, K. J., Bradley, S. J., & Sanikhani, M. (1997). Sex differences in referral rates of children with gender identity disorder: Some hypotheses. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25, 217–227.

Zucker, K. J., Wilson-Smith, D. N., Kurita, J. A., & Stern, A. (1995). Children’s appraisals of sex-typed behavior in their peers. Sex Roles, 33, 703–725.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Wallien, M.S.C., Veenstra, R., Kreukels, B.P.C. et al. Peer Group Status of Gender Dysphoric Children: A Sociometric Study. Arch Sex Behav 39, 553–560 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9517-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9517-3