Abstract

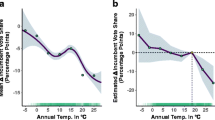

What is the relationship between precipitation and the temperature on turnout? Using data on the 2004, 2006, 2008, 2011, and 2015 Canadian federal elections, we try to answer this question. Through bivariate and multi-variate statistics, we find that each millimeter of precipitation decreases turnout by more than 0.1 percentage points. When it comes to the temperature, our results indicate that higher temperatures trigger higher turnout. However, we also find that these relationships are influenced by season and only apply to spring, summer, and fall elections. In the winter 2006 elections, the association was inversed; warmer temperatures in this election triggered lower turnout, in particular when it was combined with precipitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Although desirable, including additional elections prior to 2004 was not feasible as Canada underwent major redistricting prior to the 2004 elections.

A slightly different type of analysis distinguishes between two forms of precipitation, rainfall and snowfall, and their influence on turnout. For example, two US studies, by Gomez et al. (2007) and Fraga and Hersh (2010) find that rain has a stronger negative effect on voting than snowfall, despite its overall moderate influence.

In addition, several studies have focused on the partisan electoral implications of weather-related turnout decreases. In the majority, these studies concur that conservative parties benefit from this turnout decline. For example, Gomez et al. (2007) report that in US presidential elections every inch of rain above the election day normal results in a 2.5% increase in the Republican vote share (0.098% per 1 mm increase). Gatrell and Bierly confirm these results for the 2012 general election in the State of Kentucky. Similarly, Eisinga, et al. (2012a) find that right-leaning parties benefit from inclement weather; if the weather is bad, each right leaning party gains one seat in the Dutch parliament, whereas, left-leaning parties lose approximately one seat. Arnold and Freier (2016) highlight that in German local and state elections, rain-related turnout decreases also benefit the success of the conservative CDU, at the expense of the more left-wing SPD. Finally, Artés (2014) confirms that turnout increases due to dry and pleasant weather hurt the vote share of the Spanish conservatives, primarily to the benefit of small left-wing parties.

The studies, we cite here, measuring the influence of precipitation on turnout, normally do not control for temperature.

Matsusaka and Palda (1999) also report that rainfall does not influence electoral participation in their study.

Officially, Canada has had fixed election dates since 2007, with elections occurring on the third Monday in October. In practice, this rule was not followed either in 2008 or 2011. Although this law increases pressure to hold elections at regular intervals, to date only the 2015 election was held on the prescribed date, and the instability of minority governments makes early elections possible and even likely in the federal elections to come.

We excluded Canada’s three artic territories from the analysis. Additionally, we excluded the electoral district of Durham for the year 2004 due to the unavailability of census data.

Before the 2015 election, federal electoral districts underwent regular decennial redistricting that moved some electoral boundaries and created 30 new ridings. To account for this, our pooled models include only those 2015 districts which lost no more than 40% of their territory in the redistricting, and gained no more that 40% new territory, as calculated by the Pundit’s Guide to Canadian Elections (Funke 2017). In total, we matched 93% of the 2004–2011 districts to a 2015 district.

We used electoral districts instead of polling sub-divisions as census data were unavailable for these smaller areas. The same applies to more precise weather data.

Ideally, we would have liked to use the 2016 census for the 2015 election; however, not all the necessary data had been released at the time of data collection.

Stephen Harper’s Conservative government abolished the mandatory long-form census, replacing it with the optional National Household Survey, which collected the same information. The mandatory short-form census did continue to exist for more basic demographic data, and was used for population and age data in our sample.

We exclude the three districts of Canada’s artic territories due to their size, extreme weather, low population and incredibly different social and political realities from the rest of Canada.

Because of the different seasons during which our five elections took place, it is impossible to create one graph displaying the influence of temperature or precipitation on turnout.

Unfortunately, we could not consider early voting, which ranged from 5.5 in 2004 to 20.5% in 2015.

References

Aldrich JH (1993) Rational choice and turnout. Am J Polit Sci 37(1):246–278. https://doi.org/10.2307/2111531

Allison PD (2009) Fixed effects regression models. SAGE publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412993869

Arnold F (Forthcoming) Turnout and closeness: evidence from 60 years of Bavarian mayoral elections. Scand J of Economics. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12241

Arnold F, Freier R (2016) Only conservatives are voting in the rain: evidence from German local and state elections. Elect Stud 41:216–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2015.11.005

Artés J (2014) The rain in Spain: turnout and partisan voting in Spanish elections. Eur J Polit Econ 34:126–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2014.01.005

Bassi A (2013) Weather, mood, and voting: an experimental analysis of the effect of weather beyond turnout. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

Ben Lakhdar C, Dubois E (2006) Climate and electoral turnout in France. French Politics 4(2):137–157. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200100

Blais A (2006) What affects voter turnout? Annu Rev Polit Sci 9(1):111–125. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.9.070204.105121

Cancela J, Geys B (2016) Explaining voter turnout: a meta-analysis of national and subnational elections. Elect Stud 42:264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2016.03.005

Corvalan A, Cox P (2013) Class-biased electoral participation: the youth vote in Chile. Latin American Politics and Society 55(3):47–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-2456.2013.00202.x

Dubois E, Lakhdar CB (2007) More on the seasonal determinants of turnout: holidays and French presidential elections. French Politics; Basingstoke 5(2):144–159. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200123

Eisinga R, Grotenhuis M, Pelzer B (2012a) Weather conditions and political party vote share in Dutch national parliament elections, 1971–2010. Int J Biometeorol 56(6):1161–1165. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0504-8

Eisinga R, Grotenhuis MT, Pelzer B (2012b) Weather conditions and voter turnout in Dutch national parliament elections, 1971–2010. Int J Biometeorol 56(4):783–786. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-011-0477-7

Elections Canada (2006) Report of the Chief Electoral Officer of Canada on the 39th General Election of January 23, 2006

Elections Canada (2017) Elections Canada’s official reports—official voting results. Elections Canada, In http://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=res&dir=rep/off&document=index&lang=e#officialvoting. Accessed 16 May 2017

Feddersen TJ (2004) Rational choice theory and the paradox of not voting. J Econ Perspect 18(1):99–112. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533004773563458

Fraga BL, Hersh E (2010) Voting costs and voter turnout in competitive elections

Franklin MN (2004) Voter turnout and the dynamics of electoral competition in established democracies since 1945. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511616884

Funke A (2017) Pundits’ guide to Canadian elections. https://www.punditsguide.ca/

Gallego A (2010) Understanding unequal turnout: education and voting in comparative perspective. Elect Stud 29(2):239–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2009.11.002

Geys B (2006) Explaining voter turnout: a review of aggregate-level research. Elect Stud 25(4):637–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2005.09.002

Gomez BT, Hansford TG, Krause GA (2007) The republicans should pray for rain: weather, turnout, and voting in U.S. presidential elections. The Journal of Politics 69(3):649–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2508.2007.00565.x

Government of Canada (2017) Historical Climate Data. Retrieved on July 14, 2017 from www.climate.weather.gc.ca

Grofman B, Collet C, Griffin R (1998) Analyzing the turnout–competition link with aggregate cross-sectional data. Public Choice 95:233–246

Knack S (1994) Does rain help the Republicans? Theory and evidence on turnout and the vote. Public Choice 79(1-2):187–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01047926

LeDuc L, Pammett JH (2006) Voter turnout in 2006: more than just the weather. In: Pammett JH, Dornan C (eds) The Canadian federal election of 2006. Dundurn Press, Toronto ON, pp 305–326

Lind JT (2014) Rainy day politics—an instrumental variables approach to the effect of parties on political outcomes. Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY

Ludlum D (1989) The weather factor. American Meteorological Society, Boston

Matsusaka JG, Palda F (1999) Voter turnout: how much can we explain? Public Choice 98(3/4):431–446. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018328621580

Melo DF, Stockemer D (2014) Age and political participation in Germany, France and the UK: a comparative analysis. Comparative European Politics 12(1):33–53. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.31

Merrifield J (1993) The institutional and political factors that influence voter turnout. Public Choice 77(3):657–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01047865

Persson M, Sundell A, Öhrvall R (2014) Does election day weather affect voter turnout? Evidence from Swedish elections. Elect Stud 33:335–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2013.07.021

Rallings C, Thrasher M, Borisyuk G (2003) Seasonal factors, voter fatigue and the costs of voting. Elect Stud 22(1):65–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-3794(01)00047-6

Smets K, Van Ham C (2013) The embarrassment of riches? A meta-analysis of individuallevel research on voter turnout. Elect Stud 32(2):344–359

Statistics Canada (2006) What is north? In: Canada year book 2006. Statistics Canada, Ottawa

Statistics Canada (2012) Reasons for not voting. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/11-402-x/2012000/chap/sc/sc01-eng.htm. Accessed 15 Apr 2017

Stockemer D (2017) What affects voter turnout? A review article/meta-analysis of aggregate research. Gov Oppos 52(04):698–722. https://doi.org/10.1017/gov.2016.30

Stockemer D, LaMontagne B, Scruggs L (2013) Bribes and ballots: the impact of corruption on voter turnout in democracies. International Political Science Review 34:74–90

Studlar DT (2001) Canadian exceptionalism: explaining differences over time in provincial and federal voter turnout. Canadian Journal of Political Science 34:299–319

Verba S, Schlozman KL, Brady HE (1995) Voice and equality: civic voluntarism in American politics. Harvard University Press

Xu J (2005) Why do minorities participate less? The effects of immigration, education, and electoral process on Asian American voter registration and turnout. Soc Sci Res 34(4):682–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2004.11.002

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DTA 613 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Stockemer, D., Wigginton, M. Fair weather voters: do Canadians stay at home when the weather is bad?. Int J Biometeorol 62, 1027–1037 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-018-1506-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00484-018-1506-6